- Amy Howden-Chapman2014

- Ana Iti2020

- Andrew McLeod2007

- Andy Leleisi’uao2010

- Anoushka Akel2024

- Ava Seymour2009

- Ayesha Green2022

- Ben Cauchi2011

- Benjamin Work2024

- Bepen Bhana2016

- Campbell Patterson2015

- Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss2021

- Dan Arps2014

- Daniel Malone2014

- Emily Karaka2021

- Emma Fitts2018

- Eve Armstrong2009

- Fiona Pardington2013

- Gavin Hipkins2007

- George Watson2024

- Glen Hayward2011

- Imogen Taylor2017

- James Robinson2007

- Jess Johnson2019

- Jim Speers2010

- Juanita McLauchlan2025

- Judy Millar2006

- Kathy Barry2012

- Lisa Reihana2009

- Liyen Chong2012

- Louise Menzies2016

- Luise Fong2008

- Madison Kelly2024

- Martin Basher2010

- Matthew Galloway2025

- Michael Stevenson2023

- Moniek Schrijer2021

- NELL2023

- Neke Moa2023

- Nicola Farquhar2018

- Oliver Perkins2017

- Owen Connors2023

- Regan Gentry2012

- Richard Frater2020

- Richard Lewer2008

- Rohan Wealleans2008

- Rowan Panther2025

- Ruth Buchanan2013

- Sarah Hudson2025

- Sarah Smuts-Kennedy2016

- Sefton Rani2025

- Sorawit Songsataya2018

- Steve Carr2020

- Suji Park2015

- Tanu Gago2022

- Taro Shinoda2017

- Tiffany Singh2013

- Tim Wagg2019

- Wayne Youle2019

- Zac Langdon-Pole2022

- Zena Elliott2026

Imogen Taylor

YEAR OF RESIDENCY

January - March 2017

Imogen Taylor was born in Whangarei in 1985 and is currently residing in Dunedin as the Frances Hodgkins Fellow, after living and working in Auckland for many years.

Taylor graduated from the University of Auckland’s Elam School of Fine Arts in 2007 with a BFA and a Post-Graduate Diploma of Fine Arts in 2010. Taylor regularly exhibits with Michael Lett gallery in Auckland, as well as throughout New Zealand and internationally. In 2018 Taylor was named the Paramount award winner of the Wallace Art Awards, allowing her a six-month residency at the ISCP in New York in 2020.

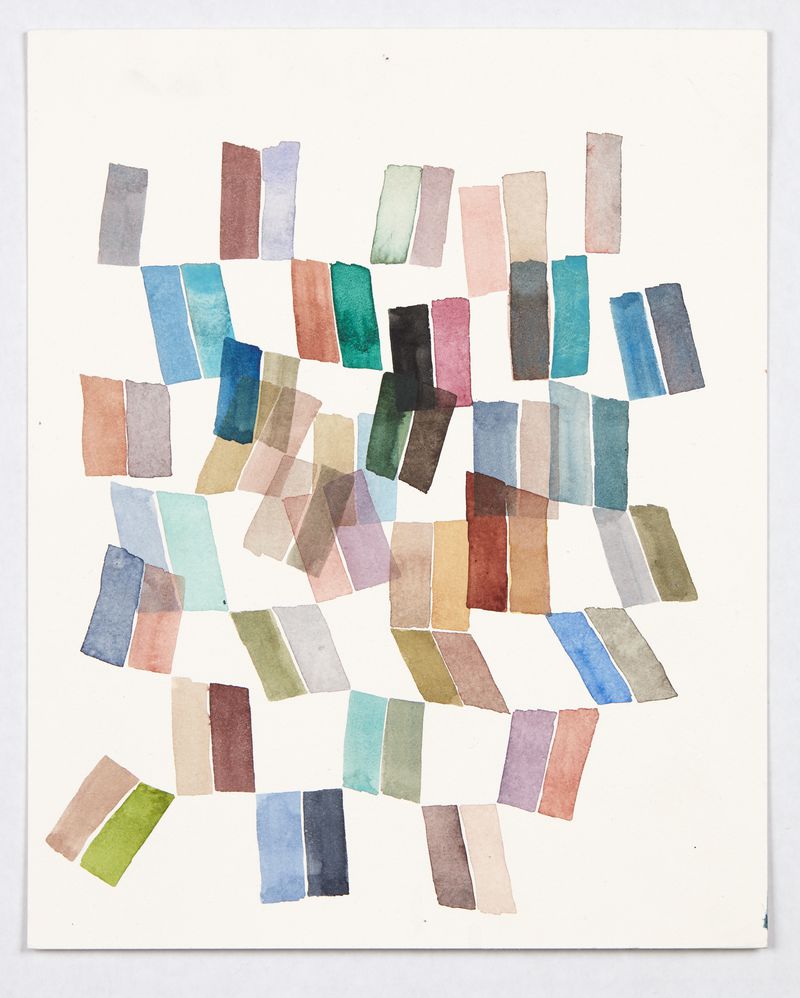

Taylor’s paintings explore art herstory through reclamation of modernist tropes: diagonals, fractured lines and forms, hessian that speaks to textile histories (specifically Bauhaus weaving), orbs that balance hard lines and vectors. Parallel to the physical act of painting, Taylor believes queerness functions as a medium that is activated by her body, and that Cubism and queer theory share multi-perspectivity; a trait that can encourage non-binary values systems when considering her paintings.

As well as painting, Taylor co-publishes Femisphere zine with Judy Darragh, a long-term publication project interested in encouraging inclusivity and visibility of women’s practices in the visual arts sector of Aotearoa.

Imogen Taylor, Rock & a Hard Place, 2019, acrylic on hessian, 1200 x 1400mm

Imogen Taylor, Shit Guitarist, 2018, acrylic on hessian, 755 x 655mm

Painting’s legacies and the ongoing questions of its relevance sit like a monkey on Imogen Taylor’s shoulder. And the monkey is muse. New terms like ‘precariat’ have been invented to name the insecurity which Taylor’s generation faces. Imagine being a painter her age now. The status updates on painting’s health are like those collapsible wooden toys that you stick your finger up – one minute it’s limp, buckled-in on itself, the next it’s spry, upright. If painting is dead, imagine what the funeral – probably at MoMA – would look like: Paul Delaroche, Andy Warhol, Donald Judd, Marcel Duchamp as pallbearers? In a 2015 discussion on painting’s relative wellbeing, critic Jason Farago identified the medium’s pluralisms: the recent uplift of figurative painting; work that’s moved off the canvas; artworks that combine painting in installations. Farago argues that painting which ‘acknowledges the challenges the medium has faced and builds from there is doing very well indeed’.1 The evolution of new painting sub-species – the figure in frame again, the painting playing with its frame and, in some cases, joining a room of other stuff – may be a sign that hybrid vigour will keep things spry and upright. But when I look at recent painting, it’s those painters whose DNA is visibly located in modernism which hold my attention and signal health.

Taylor is a painter who finds reserves in a range of visual modernisms. Her plumbing of local art history has been widely discussed, sometimes shallowly as an unthinking homage to formalism.2 But close looking reveals Taylor’s thoughtful, broad sampling and remixing process in which pieces of geometric abstraction from early and mid- 20th-century art are overlaid and recharged. Her 2016 exhibition In & Out at Michael Lett Gallery presented a selection of works that refracted colour, shapes, form and space. In Orbit Around, 2016 (fig.1) De Stijl-like pixels awkwardly interact on the canvas with Delaunay-esque arcs. Your eye jerks across different layers; sections emerge and interrupt each other on the plane. One minute you might be in an industrial city; the next you’re close-up to a piece of fabric. Clanging, sometimes discordant colour harmonies intersect with divided orbs and colour swatches in Charlie’s Bar, 2016 (fig.2). The lack of compositional equanimity means that you work with the paintings to achieve what’s often just a fleeting stable reading. In the homage to local Cubism, Full Moon/King Tide, 2016 (fig.3) Colin McCahon’s ‘little squares’ dance at you and drift away inside a field of overlapping shapes. Parts of the structure resemble – vaguely – solid forms; while in other areas, which are more open, flattened beams lean and lurch, overlie and tuck behind. These paintings are uneasy: it’s difficult for the eye to find fixture when pitching into something close then jerking back out. The exhibition title – In & Out – might be seen to reference both this pitching effect and the questions: “What’s in and what’s out”? Is Taylor alluding to the formal mechanics in which forms are revealed and concealed, or maybe her relationship with modernism and its new blush? Is she talking about making love – or passing through passion?

Resonant with Cubist legacies, Full Moon/King Tide anticipated Taylor’s latest body of work, which itself represents a continuation of ideas developed during her McCahon House residency in 2017. Out in Titirangi, suspended in the bush, Taylor was closer to a home grown source of her sampling. Like housesitting for Gertrude Stein, immersed in French Bay and its environs, she was surrounded by a memory of modernism. More than 60 years earlier, McCahon had been in the midst of a transition towards overtly modernist forms. He made this move there by way of Cubism. His merging of cubist elements with kauri, religious texts and views of the bay at the end of the road represented a period of development as well as a bedding in. A modernism with strong links to its European genesis was taking root as Cubism helped McCahon break open his painting and relinquish mimesis. The cubist-inspired hybrid painting produced in the 1950s reflects his largely independent and isolated study of the development of abstraction, which of course had happened elsewhere first. The cubist style was for him a toolkit which he used to understand non-naturalistic representation. Yet his work remained anchored in the reality of his everyday life and its translation of optical perception. Taylor’s motivations, separated scores of years from McCahon’s, may appear very different. Are they? Exploring visual modernisms, including Cubism and post-cubist styles, she translates modern elements into her own restless abstraction. Informed by revolutionary theories of time, cubist painting had its beginnings in the transformation of perceptions of objects in space through the fusion of multiple views within a single image. Back out at the McCahon House in 2017, Taylor wasn’t busy swatting Cubsim’s handbook – Du ‘Cubisme’, 1912 – or applying stringent theories to the construction of still lifes. She was intuiting Cubism’s geometric and often organic-looking forms, reimaging pockets of modernist vocabulary.

In the robust and explorative Foot Hills, 2017 (fig. 4), emphasis shifts as the networks of flat planes and pattern in the earlier In & Out works are replaced by more heavily rendered curvaceous shapes. Folded and sliced, the forms of Foot Hills simultaneously elide and divide. This brings the work of North American painter Lesley Vance to mind: her compositions were not predetermined but were instead the results of finely poised arrangements ‘built on the logic of suspension’.3 And like McCahon, Taylor uses straight lines and curves to construct a stratum of interjecting shapes which seem in parity with each other. Unseen forces push and tug at forms which are pricked, flaccid or puffed-up. The chaotic equilibrium of Foot Hills is also reminiscent of the movement in German artist Florian Baudrexel’s angular sculptures and the pointed elements of the Umberto Boccioni bronze Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, 1913. It’s worth at this point noting that painting wasn’t Taylor’s art-school major.

Foot Hills’ physicality, which transcends ‘sampling’, recalls the works Taylor presented in the suitably named 2015 exhibition Body Work at Artspace, where a sense of the abject found expression in a messy yet measured churn of modernist leitmotifs, bulbous shapes and holes. Transgressive and trypophobia-inducing, the Body Work paintings merged forms evocative of body parts with the taut language of geometric abstraction. Slip, from 2016 (fig. 5), is also characterised by this ‘“pretty/ugly” mix’4, but with more explicit imagery as a black column/baton pushes down on the centre of the pillow and threatens the balance of the stack of parts beneath, bringing to mind the fragile delicacy of the human head. Slip’s dark humour announces a degree of forcefulness and menace not present in Taylor’s more ‘decorative’ work.5

Textures of local modernism, as well as those of European modern art, are props in what I would call ‘Taylor’s tragicomedies’. In the exhibition Body Work, we found Picasso’s rope, unfurled from the oval edge of painting’s first collage – Still Life with Chair Caning, 1912 – to be used as a hanging device and dangled through holes which punctured Taylor’s compositions. The hessian surface of Foot Hills echoes the back-of-the-Masonite-board period feel of a 1950s John Forrester still-life painting (fig. 6); or, somewhat perfectly, the temporary partition walls visible in the installation images of the 1954 exhibition Object and Image. Curated by McCahon and featuring work by him and other New Zealand cubists, Object and Image represents an opening up to international art and a pivotal moment in New Zealand’s evolving conversation with abstraction. Taylor, working in the 21st century and connected beyond measure with the international through technology and easy travel, is informed by an entirely different set of conditions. Although her works may hover ‘between authenticity and appropriation’,6 and sometimes issue uneasy jibes, her understanding of the ramifications of geometric abstraction’s impossibly male-dominated history – its painters and critics alike – is clear. If you want this further elaborated, ask her to write you a zine about it.

After Obama became president, Joan Didion stated that irony had become ‘not the preferred way’ of viewing events.7 The same cannot be said for Taylor’s Instagram, which may well offer a useful perspective on her practice. In a photo uploaded with the caption ‘Our very first family portrait’, the artist poses in a shiny puffer jacket. Beside her stands Sue, who is dressed in a multi-coloured patchwork ski jacket from the early 1990s. Does the lampooning of heteronormative traditions flow into the art? Is Taylor’s referencing of visual modernism poking fun at the ‘authentic gesture’ of mid-century painting? Perhaps an answer lies in her finely applied brushstrokes and in the complexity of her compositions. Her carefully crafted paintings may slip between the poles of homage and irony, but in her uneasy abstraction and hectic attitude towards form I find certain and knowing sincerity.

In combating, or at least working within, a disillusionment with painting, Taylor looks to history – to 20th-century European Cubism and its southern-hemisphere offspring. At its inception, Cubism transgressed bourgeois rationality to create a style of disruption and discomfort. Those analytic masterpieces of confusion, all in differing shades of grey, were full of eye-trickery, word play and humour. In the later work of New Zealand-based cubists, struggle lay on the surface, visible and attention calling. Each hard-edge line, flattened plane or translucent screen of colour reached towards new painterly possibilities. Merging McCahon with his influences, Taylor, in a very 21st-century, all-things-connected manner collapses the distance between the local and the international, while feeding the local back to the international. Her ironic sensibility – ‘the detachment of mind, the appreciation of the folly of taking things at face value’ – reminds us that the modernists’ utopian prospecting may have fallen short.8 Didion cautioned against living in an ’irony-free zone’ in which ‘naïveté, translated into “hope” was now in’ and where’ innocence, even when it looked like ignorance, was now prized’.9 Thankfully, Taylor’s refracting and ironic lens breaks the path to easy viewing, disrupting the potential for cosy or nostalgic or innocent readings of mid century formalism. Her bent forms show a knowing understanding of the politics of painting and its histories, which alerts us to the wider risks of simple and blinkered looking.

Essay commissioned by the McCahon House Trust on the occasion of Imogen Taylor's residency and resulting exhibition Pocket Histories, 10 February – 13 May 2018, at Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery

- BBC: Jason Farago: Is Painting Dead? 18 February 2015. http://www.bbc.com/culture/

story/20150217-is-painting-dead, accessed 21 Jan 2018. - New Zealand Painting: Stealing the Show: Implicated and Immune: Historical Revisionism. http://www.newzealandpainting.co.nz/2015/02/stealing-the-show-implicated-and-immune-historical-revisionism/comment-page-1/, accessed 21 Jan 2018.

- S. Hudson, Painting Now. (London: Thames and Hudson, 2015), 198.

- Noted: Julie Hill: Auckland Artist Imogen Taylor Contemplates the Art World Sausage-ocracy http://www.noted.co.nz/culture/arts/auckland-artist-imogen-taylor-contemplates-the-art-world-sausage-ocracy/

- Ibid.

- Mark Godfrey, ‘Statements of Intent’, Artforum, (2014): 295.

- New York Times: Andy Newman: Irony is Dead. Again. Yeah, Right. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/23/fashion/23irony.html, accessed 21 Jan 2018.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

Artist Artworks

A work produced and gifted by the artist at the conclusion of their residency in support of the ongoing work of the McCahon House Trust.

Imogen Taylor

Whatever leads me to you

2017

inkjet print, edition of 3

207mm x 254mm

Collection of McCahon House Trust

Sold out

Imogen Taylor

Couch Navigation

2017

inkjet print, edition of 3

207mm x 254mm

SOLD

Imogen Taylor

Fonds/Guides

2017

inkjet print, edition of 3

207mm x 254mm

Collection of McCahon House Trust

Sold out