- Amy Howden-Chapman2014

- Ana Iti2020

- Andrew McLeod2007

- Andy Leleisi’uao2010

- Anoushka Akel2024

- Ava Seymour2009

- Ayesha Green2022

- Ben Cauchi2011

- Benjamin Work2024

- Bepen Bhana2016

- Campbell Patterson2015

- Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss2021

- Dan Arps2014

- Daniel Malone2014

- Emily Karaka2021

- Emma Fitts2018

- Eve Armstrong2009

- Fiona Pardington2013

- Gavin Hipkins2007

- George Watson2024

- Glen Hayward2011

- Imogen Taylor2017

- James Robinson2007

- Jess Johnson2019

- Jim Speers2010

- Juanita McLauchlan2025

- Judy Millar2006

- Kathy Barry2012

- Lisa Reihana2009

- Liyen Chong2012

- Louise Menzies2016

- Luise Fong2008

- Madison Kelly2024

- Martin Basher2010

- Matthew Galloway2025

- Michael Stevenson2023

- Moniek Schrijer2021

- NELL2023

- Neke Moa2023

- Nicola Farquhar2018

- Oliver Perkins2017

- Owen Connors2023

- Regan Gentry2012

- Richard Frater2020

- Richard Lewer2008

- Rohan Wealleans2008

- Rowan Panther2025

- Ruth Buchanan2013

- Sarah Hudson2025

- Sarah Smuts-Kennedy2016

- Sefton Rani2025

- Sorawit Songsataya2018

- Steve Carr2020

- Suji Park2015

- Tanu Gago2022

- Taro Shinoda2017

- Tiffany Singh2013

- Tim Wagg2019

- Wayne Youle2019

- Zac Langdon-Pole2022

- Zena Elliott2026

Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss

YEAR OF RESIDENCY

September - December 2021

Parehuia Education Resource: Cora-Allan, 2021

Gate XI Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss x Daniel Twiss & Ruby White - April 2022

Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss is a multidisciplinary artist of Māori and Niue descent, originally from Waitakere. In 2013 she completed her Masters in Visual Art and Design from AUT, also receiving an AUT Postgraduate Deans award for her research and excellence. She returned to Aotearoa in 2016 after working at the Walter Phillips Art Gallery in Banff, Canada. Cora-Allan is a full-time practitioner of Hiapo and is a founding member of BC Collective.

Pictured: Cora-Allan Wickliffe's studio at Parehuia, 2021. Photograph: Raymond Sagapolutele

Cora-Allan Wickliffe came to the McCahon House Residency with three immediate members of her own whānau at her side; fiancé Daniel Twiss, and sons Chaske-Waste (Aged 5) and Wakiya-Wacipi (Aged 2). Upon arriving, Tāmaki Makaurau was transitioning into Level Three lockdown after five restrictive weeks at Level Four. Wickliffe would have been forgiven for wanting some time alone to focus on making, having just been confined to her own home with two young sons. That, however, did not once cross her mind.

For Wickliffe, life with her whānau is an intrinsic part of her art practice. This is perhaps unsurprising, given that she is a contemporary Hiapo practitioner. Hiapo is the barkcloth of Niue made from the ata (mulberry tree), and Wickliffe is recognised for her traditional pieces alongside her more simplified, modern Hiapo works. In her first publication, Hiapo: A Collection of Patterns and Motifs, Wickliffe writes, “Niuean Hiapo is like a time capsule giving you an artist’s interpretation of the land, the sea and the people from their era.”1 This sentiment has remained at the heart of her practice, which over the past year, has grown to incorporate a wider range of mediums including works on paper and wooden panel, sculpture and ceramics. As someone who seeks to include her whānau and community in openings, workshops and making, the residency meant she pondered new ideas around how those she loved could be a part of her art. Adversely, she wanted the residency to become not only a space of making for herself, but also a meaningful experience for her whānau in a more immersive creative environment.

Wickliffe clearly embraces the push and pull between being an artist and being a mother. She navigates these roles fluidly, with each enriching, informing and being an integral part of the other. Undertaking a residency with a young family is no small feat, and the whānau had to learn to navigate their new environment and routine together. She confides that her favourite moment was when all four of them, lying underneath the skylight on the kitchen floor, watched raindrops fall from the canopy of kauri onto the glass below. Although effortless at times like that, the entwined roles of Parent and Artist (and in fact, Fiancée) make up a delicate multi-hyphenate that simultaneously requires balance and boundaries. Wickliffe’s young sons and partner understand the importance of her work. When it came time to wind down during the evenings, Daniel stepped in to become their sons’ person while she retreated to work in the conjoining studio for the night.

The experiences of how McCahon navigated family life were on Wickliffe’s mind and prompted reflection on the lifestyle of her own whānau during their time in Titirangi. For a change of scenery, she would often take her sons down the path to visit the McCahon House where she found herself making natural comparisons between how the McCahon family lived over this time, and how her own were experiencing their time at Otītori Bay Road. McCahon was often away from his family during these years, either painting in his studio, or making the long journey into Central Auckland where he taught at the Auckland Art Gallery and later the Elam School of Fine Art.2 In contrast, Wickliffe’s time over her residency concluded her first year as a full-time artist, which marked a shift for her whānau in navigating the artist lifestyle together. For Wickliffe, art should be folded into the family experience, there is never a time when it is the most important thing in the equation. This is most plainly evident in all four of the young whānau being together, even when mum has a three-month long residency in a different suburb.

Wickliffe’s time at the residency has undoubtedly been her most prolific. It feels all the more exceptional knowing she was not there alone but sharing the space with her sons and partner. She produced a staggering 320 works across Hiapo, watercolour paper and wooden panel, the latter two being more experimental mediums that she found a new freedom to explore. The wooden panel was especially needed to carry her palette of whenua paints using pigments she harvested from the local landscape. She also turned to the plywood panels to paint various landscape series, often in groups of 10 as she experimented with the visual forms and consistency of the pigments. The thickness of these new paints, named after their Te Kawerau ā Maki whenua, meant that the even denser surface of the wooden panels could carry them differently to how a more porous Hiapo had before. What followed was a refreshed interest in landscape, in a bid to interpret her whānau’s new surroundings.

Soon, the pull of moana at Otītori Bay took a central role for Wickliffe and whānau over the residency. The water offered both an extension of the studio and a space for her wider whānau to experience together. They were often joined at Otītori Bay by Wickliffe’s siblings and her father, Kelly Lafaiki, with whom she has a treasured close relationship. As a unit, the whānau paid attention to the tides and the rhythm of the seaside, particularly with the arrival of a small wooden rowboat that would take Wickliffe out onto the water. Sadly, the passing of Wickliffe’s Koro (maternal grandfather) over this time meant another new experience for the whānau; the Tangi of a loved one online. This foreign, disconnected experience of grief marked yet another venture into unfamiliar ground. It also meant that her small wooden rowboat had found its name. Koro transported Wickliffe over the water, carrying her safely around Otītori Bay and affording her a different perspective of the local landscape. While her sons and their cousins could be carried by Koro together in the shallows, venturing deeper was a solo journey with no room for another as she rowed. Watched closely by her steady father ashore, she would make rapid charcoal sketches of the landscape in a series of small bound sketchbooks from her new vantage point. The experimentations unveiled a completely new interpretation of both landscape painting and Hiapo tradition, specific to Titirangi and Otītori Bay, and the whānau’s time there.

The ocean played an unexpected new role in the residency works, and it took form as something like a collaborator - a concept familiar to Wickliffe. Hiapo tradition places importance on an interpretation of people, and encompassing her whānau and those around her in the making experience feels like Wickliffe’s unique way of doing this. Collaboration then seems obvious, particularly with her immediate whānau whose lives are deeply intertwined in the art, and vice-versa. Prior to the residency, collaboration came in many forms. Together with fiancé Daniel, the pair founded BC Collective (BC stands for ‘Before Cook’ and ‘Before Columbus’) at Corban Estate Arts Centre in 2017, to share and exchange Indigenous ideas and concepts. Then alongside her paternal grandmother, Fotia Lafaiki (Nana), Wickliffe researched and published Hiapo: A Collection of Patterns and Motifs which records the patterns and symbols she has collected in her journey with Hiapo. These ongoing ways of bringing whānau into the creative process have been most embodied in the residency. Wickliffe’s eldest son Chaske-Waste would accompany her to harvest pigments, and both boys would venture into the studio over the course of their days between trips down to the beach. On one of his visits, Wickliffe’s father Kelly explored the McCahon Cottage and captured photographs of the architecture that appealed to him about the heritage space. Taking these photographs, Wickliffe then sketched a suite of postcard-like works on paper interpreting what her father had seen. The process meant that just like with the nearby ocean at Otītori Bay, she was afforded a fresh perspective - this time through her own father’s eyes.

The large studio at the residency afforded Wickliffe the physical space and time to create her largest Hiapo work to date. Measuring five by four metres the work is pivotal not only in scale, but in the incorporation of traditional Hiapo patterns alongside small fragments of still life in ink, and washes of whenua paint, together in the composition. Significantly, it is also the first work that depicts her whakapapa, through stories of her Niuean grandparents' life in both Niue and Aotearoa. Quirky details like a symbolic rendition of an old car that frequently appeared in tales from her grandparents’ life in Niue are depicted on the immense surface of the work. It is generous in how deeply personal it is. Wickliffe explained that before now, these stories marked by her grandparents’ struggles simply felt too precious to give up to the world. Having her sons walk across the immense Hiapo while it is unfurled on the studio floor, she feels its importance and holds a renewed confidence in taking her own path as an artist with her young whānau at her side.

Wickliffe’s residency experience demonstrates the power of whānau and just how much is possible within the artist lifestyle. Her practice feels as though it has taken a turn, in how it is folded so intricately into her whānau’s day to day life. In an Instagram post, she writes;

“I get goosebumps knowing our little ones will grow up with their Mamas and Aunties making cloth, and have strong memories with Hiapo. They will grow up with it on the walls and in their cribs, they will remember wearing it on special occasions and when we use it to say goodbye to loved ones. Hiapo is not just art, it ties us back to our Tupuna and it’s very much embedded in my family’s lives. I can’t wait for other families to have this too.”3

Essay commissioned by McCahon House on the occasion of Cora-Allan Wickliffe's residency September - December 2021.

Photographs by Raymond Sagapolutele.

[1] Cora-Allan Wickliffe. Hiapo: A Collection of Patterns and Motifs. (2020).

[2] Peter Simpson. Colin McCahon: The Titirangi Years 1953-1959. (2007).

[3] Instagram Post via @coraallanwickliffe, 02 October 2020. (Accessed 10 January 2022).

Artist Artworks

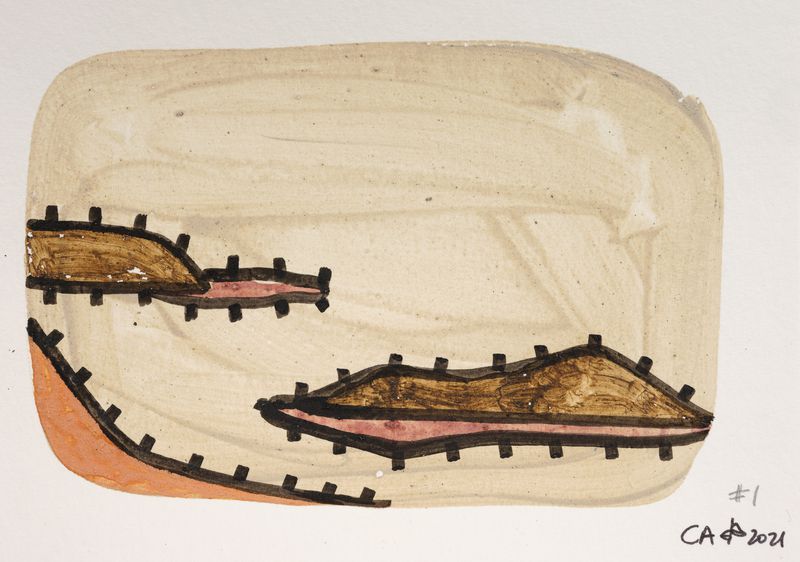

Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss

#1

2021

whenua pigments made by the artist on Hahnemuhle watercolour paper

105 x 148mm

$500 (unframed)

Photo: Sam Hartnett

Contact us to purchase this edition.

Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss

#2

2021

whenua pigments made by the artist on Hahnemuhle watercolour paper

105 x 148mm

Collection of McCahon House Trust

Photo: Sam Hartnett

Sold out

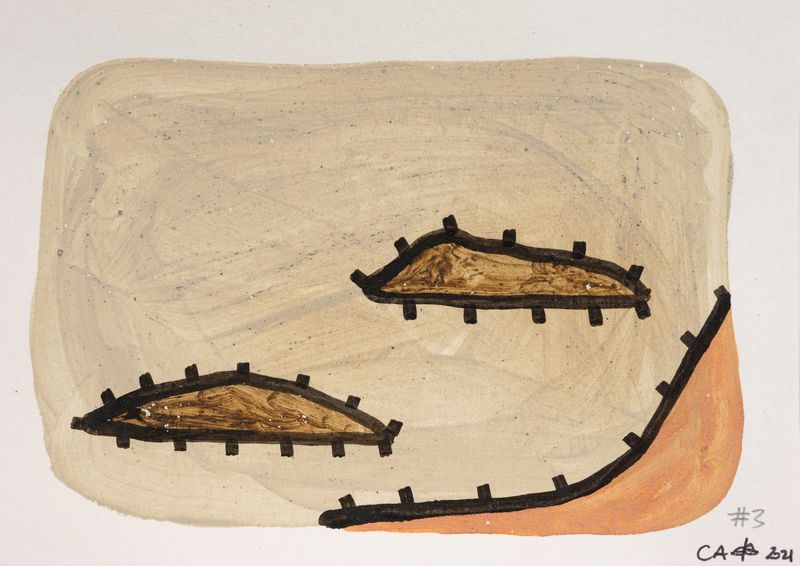

Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss

#3

2021

whenua pigments made by the artist on Hahnemuhle watercolour paper

105 x 148mm

$500 (unframed)

Photo: Sam Hartnett

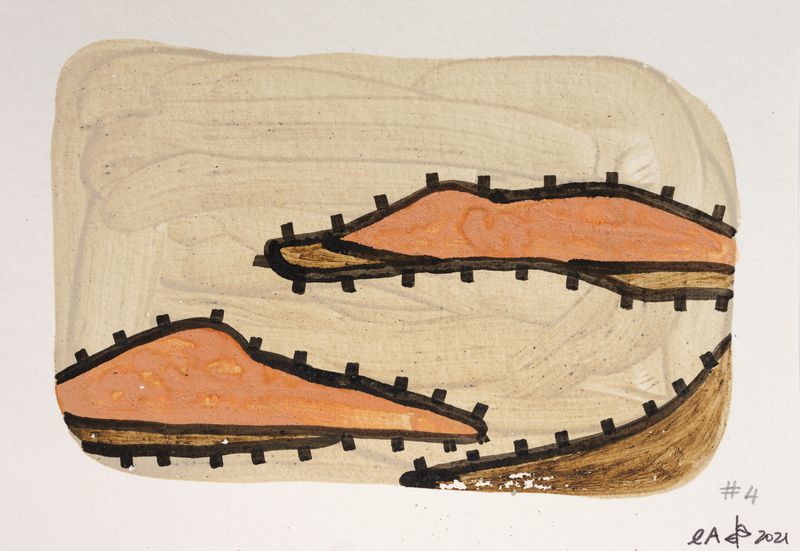

Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss

#4

2021

whenua pigments made by the artist on Hahnemuhle watercolour paper

105 x 148mm

$500 (unframed)

Photo: Sam Hartnett

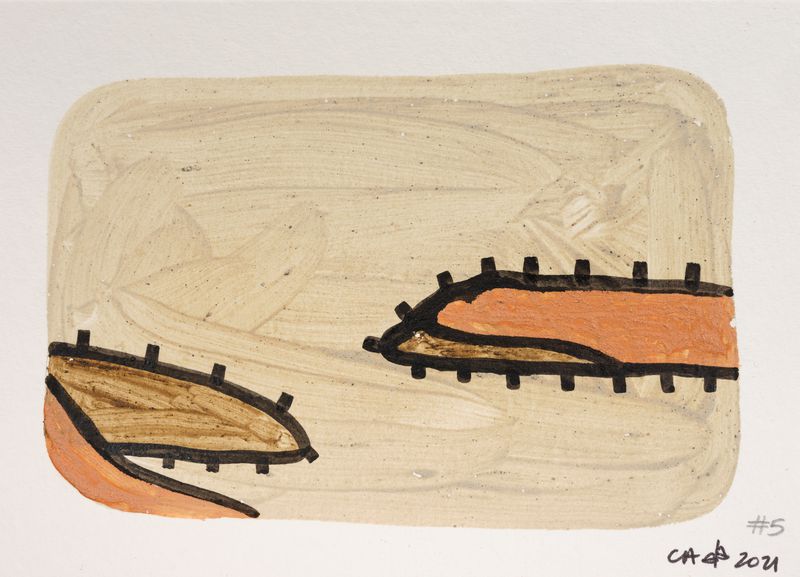

Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss

#5

2021

whenua pigments made by the artist on Hahnemuhle watercolour paper

105 x 148mm

$500 (unframed)

Photo: Sam Hartnett

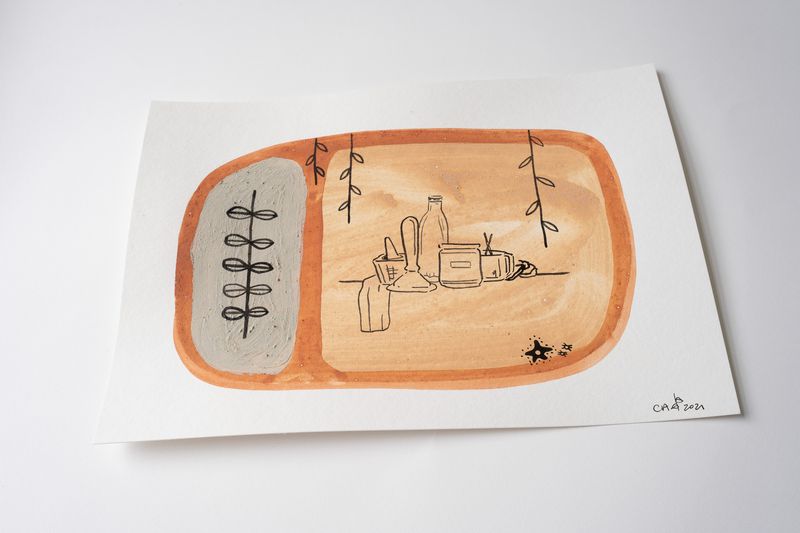

Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss

Untitled

2021

whenua pigments made by the artist on Hahnemuhle watercolour paper

210 x 300mm (paper)

$950 (unframed)

Contact us to purchase this edition.