- Amy Howden-Chapman2014

- Ana Iti2020

- Andrew McLeod2007

- Andy Leleisi’uao2010

- Anoushka Akel2024

- Ava Seymour2009

- Ayesha Green2022

- Ben Cauchi2011

- Benjamin Work2024

- Bepen Bhana2016

- Campbell Patterson2015

- Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss2021

- Dan Arps2014

- Daniel Malone2014

- Emily Karaka2021

- Emma Fitts2018

- Eve Armstrong2009

- Fiona Pardington2013

- Gavin Hipkins2007

- George Watson2024

- Glen Hayward2011

- Imogen Taylor2017

- James Robinson2007

- Jess Johnson2019

- Jim Speers2010

- Juanita McLauchlan2025

- Judy Millar2006

- Kathy Barry2012

- Lisa Reihana2009

- Liyen Chong2012

- Louise Menzies2016

- Luise Fong2008

- Madison Kelly2024

- Martin Basher2010

- Matthew Galloway2025

- Michael Stevenson2023

- Moniek Schrijer2021

- NELL2023

- Neke Moa2023

- Nicola Farquhar2018

- Oliver Perkins2017

- Owen Connors2023

- Regan Gentry2012

- Richard Frater2020

- Richard Lewer2008

- Rohan Wealleans2008

- Rowan Panther2025

- Ruth Buchanan2013

- Sarah Hudson2025

- Sarah Smuts-Kennedy2016

- Sefton Rani2025

- Sorawit Songsataya2018

- Steve Carr2020

- Suji Park2015

- Tanu Gago2022

- Taro Shinoda2017

- Tiffany Singh2013

- Tim Wagg2019

- Wayne Youle2019

- Zac Langdon-Pole2022

- Zena Elliott2026

Sefton Rani

YEAR OF RESIDENCY

January - April 2025

Sefton Rani is a self-taught artist of Cook Island heritage who lives and works in Tāmaki. He has had an ongoing practice for over a decade, exhibiting and engaging with a range of galleries and public institutions across Aotearoa. Rani's work is an investigation into Pasifika identity within the context of working class and industrial Auckland. He explores the materiality of paint, experimenting with the boundaries between painting, sculpture, carving, and heritage art through process-driven works that capture the physicality of his mark making methods and reference a history of labour and cultural production. Sefton's time at Parehuia will mark a transformational point in his career as an artist. After his home and studio were destroyed by cyclone Gabrielle in 2023, he was forced to adapt and develop his work in response to these changed circumstances. Displacement, both physically and spiritually, becoming a key narrative. During his residency, Rani intends to further extend these ideas into a new, unified direction and body of work.

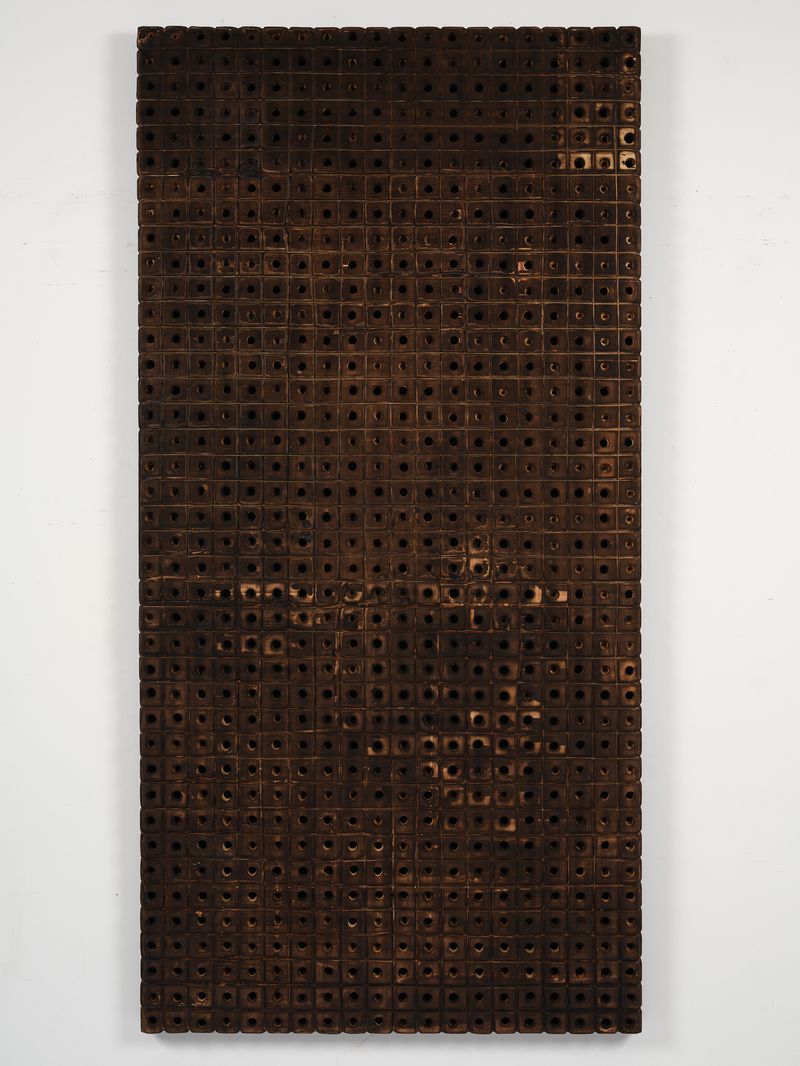

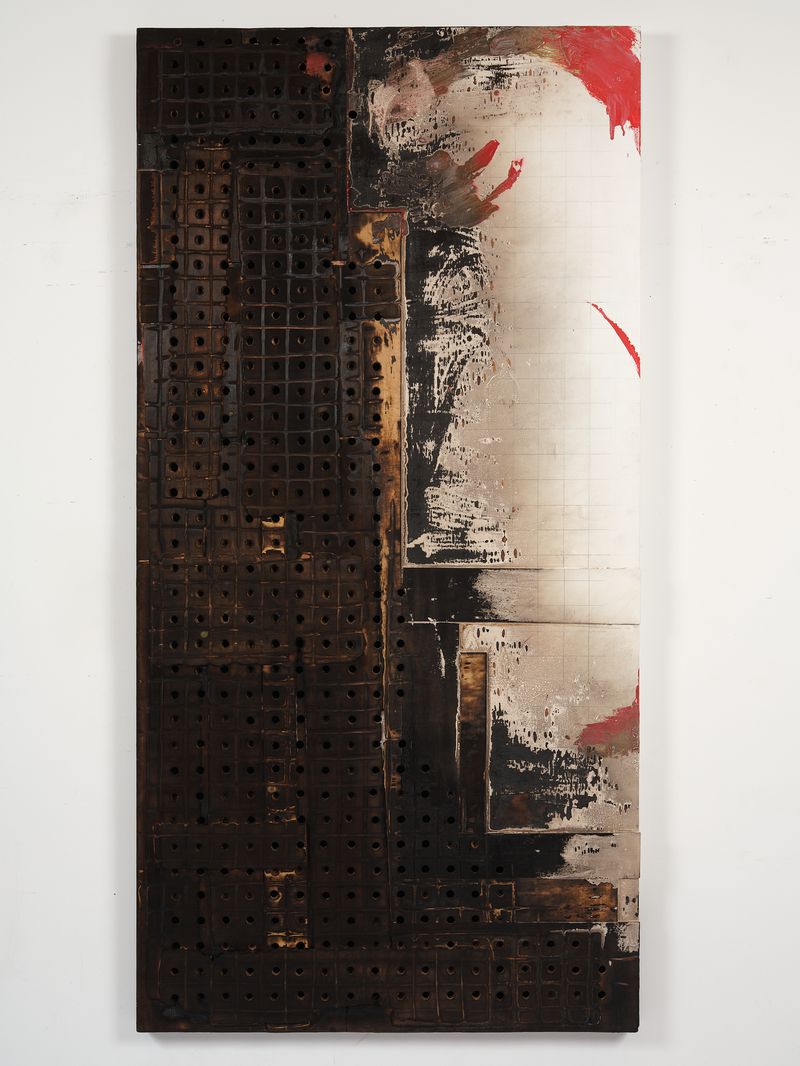

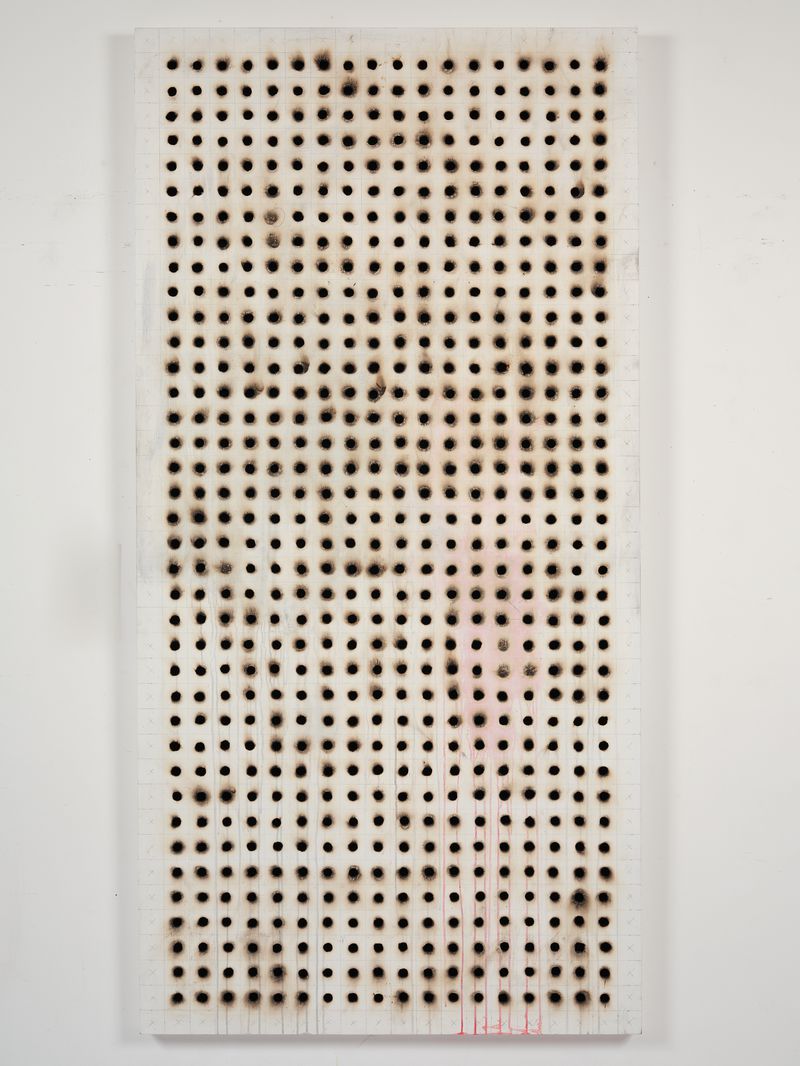

Gabrielle, panel 1 of 6, 2025 (image courtesy of Samuel Hartnett)

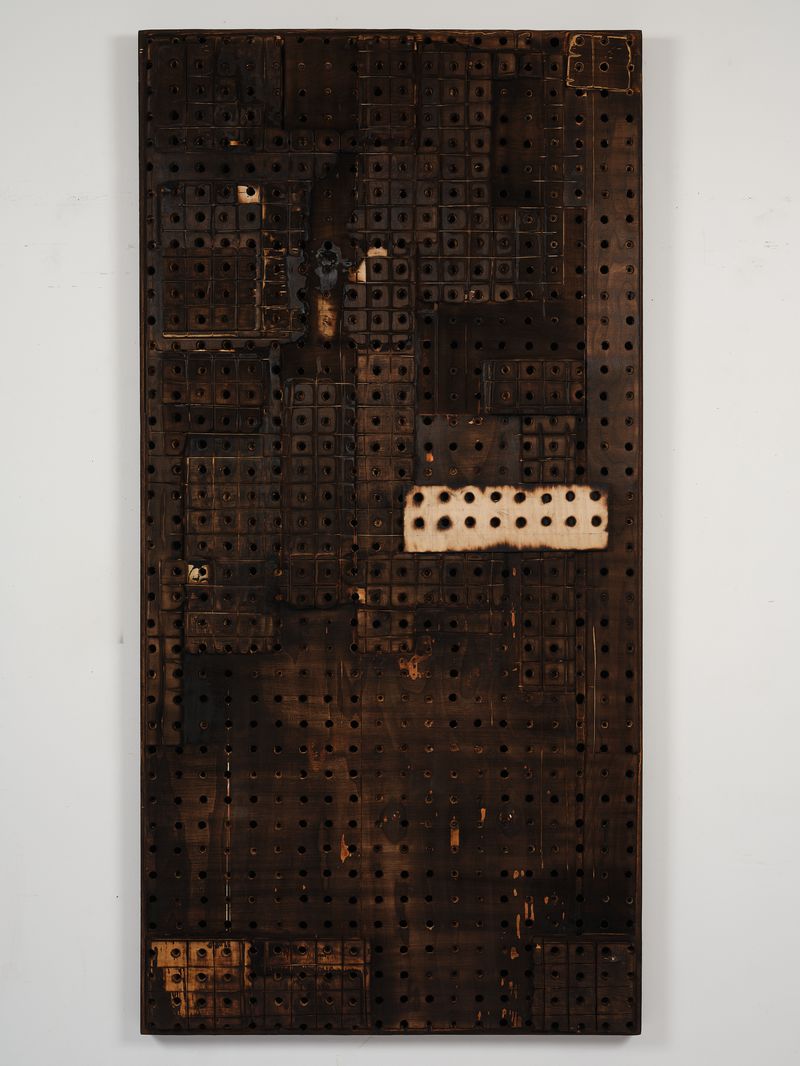

Gabrielle, panel 2 of 6 2025 (image courtesy of Samuel Hartnett)

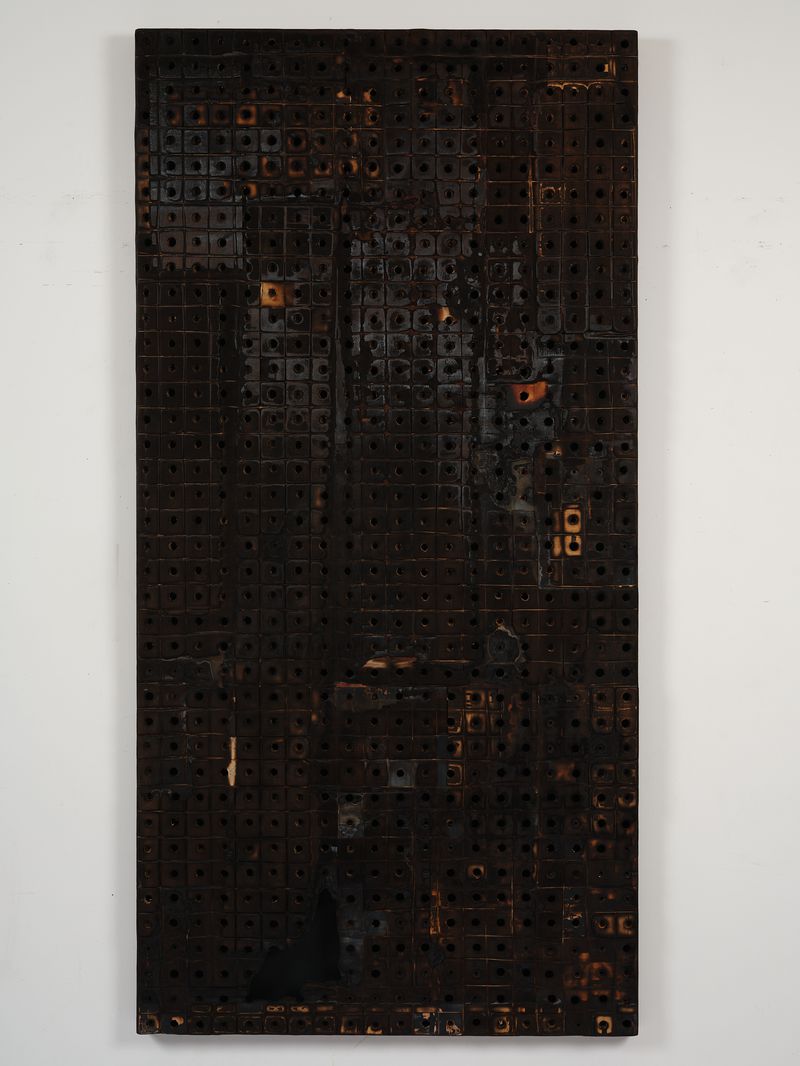

Gabrielle, panel 3 of 6, 2025 (image courtesy of Samuel Hartnett)

Gabrielle, panel 4 of 6, 2025 (image courtesy of Samuel Hartnett)

Gabrielle, panel 5 of 6, 2025 (image courtesy of Samuel Hartnett)

Gabrielle, panel 6 of 6, 2025 (image courtesy of Samuel Hartnett)

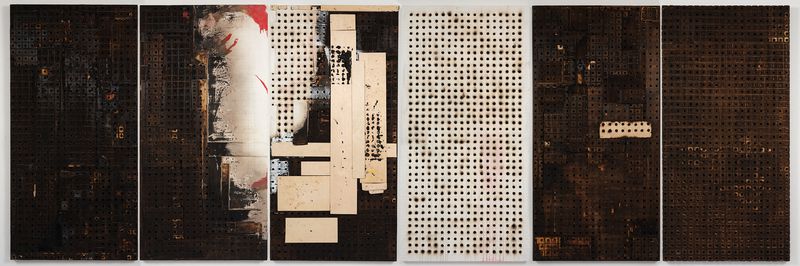

Gabrielle, 2025, image by Samuel Hartnett

On arrival at Parehuia, Sefton Rani crafted a pou to signal the transition from domestic to working space, where an uncovered deck mediates between the living quarters and the studio’s mezzanine entry. Installed prone and serpentine along the mezzanine’s half wall – anchoring the edge of the landing and framing the void of the stairwell as it drops into the studio – it materialised both connection and scission, prompting the residency’s spaces to cleave at once together and apart. Below this newly created horizon gathered the materials and labour for a monumental work: six blank panels, a space redolent with presence, and a maker without a predetermined plan but with a desire to sit in place and take in the energy.

A found object first suggested a way to lean into the opportunity offered at McCahon House, in a studio nested in kauri forest like a birdhouse. On a walk up Otitori Bay Road to Titirangi, Rani found a survey marker – a metal plaque used to establish property boundaries – dislodged and displaced by recent storms. Back at the studio, it was a catalyst for thinking about land, lineage, and loss, and became a substrate for one of Rani’s signature paint-skin works. These time-consuming sculptural paintings are built layer upon layer over a period of several months, drying slowly to become ‘industrial tapa’. Here, paint is not simply a surface dressing but a hefty, dense material in its own right. Rani later reflected that in the results of the paint-skin process, the marker’s text appears in reverse, offering a way to consider not the claiming of space but its relinquishment: the losing of land, rights, and belonging. This insight seeded the eventual form of the residency’s major work, Gabrielle, and its relationship to place.

Rani knows paint. He understands paint structurally: how pigments sink or float, how solvents evaporate, and how heat releases colour into a gas. He knows plywood, metal, fire, fragmentation and dissolution. His materials behave like performers responding to decades of embodied knowledge. Paint becomes tapa; burning becomes painting; surface fissures speak to cultural fractures, environmental upheaval, and the ruptures of diaspora.

His formative years in the paint factory, where his father worked, and where he spent his school holidays and the first months after leaving school, shaped his relationship with materiality long before he accepted the mantle of artist. His father, a paint shader, developed a deep sensitivity to colour that Rani believes he may have inherited – an intuitive ability to read chromatic nuance. In the factory, paint was an unruly substance splattered across floors, overflowing from vats, dripping through mesh filters, and hardening into layered stalactites of pigment accumulated over decades. Looking back, he connects these industrial residues with the turps-heavy drips and splatters in Ralph Hotere’s work. Yet they were first encountered not as art-historical gestures but as the everyday by-products of labour, accident, and chemical process. His later experimentations – heating, stripping, microwaving, and otherwise provoking paint – replay this early exposure to the factory floor as a site where materials continually challenge expectations.

At Parehuia, the long histories embedded in the studio’s surfaces recalled this inheritance, and the tabletops mottled with years of other artists’ spills and imprints became, for Rani, another kind of factory floor. He cast paint-skins directly on these worktables to capture the residue of the residency itself, making visible the accumulated traces of those who came before. In this way, the aesthetic possibility of paint-skins became a method for honouring place, labour, and lineage, allowing the studio’s material memory to be seen and held.

This interest in material residue extends across Rani’s wider practice. Second skins, embedded objects, hidden motifs, and densities of mark-making evoke the wrapped gods of his father’s homeland, Mangaia, and other vessels of knowledge whose significance lies partly in what they conceal. Bringing an urbane sensibility to this approach, he embeds staples within his layered works to evoke the sight of city lampposts covered with posters. Whereas paper quickly decays, he explains, the staples remain in place as indicators that something once existed here and has since been lost. These tiny metal remnants echo cultural loss, missing genealogies, fragmented narratives, and encounters with the half-remembered.

Gabrielle

Working in charcoal at first, Rani let Parehuia shape his thoughts: the stillness, the sense of presence, the lingering scent of labour. Gradually, one panel emerged, and then another, as if coaxed from a place beyond deliberate intention. Each panel was layered from plywood, glued, cut, chiselled, drilled, painted, and burned. The burning could only happen at his home, on a concrete pad behind his house. Thus, the work holds a connection between the two places where it was made: Parehuia and Rani’s house in Papakura.

The panels carry traces of both sites. They were carried up and down steep paths, transported between Parehuia and his home, and then burnt and scrubbed clean – an essential part of his process. The drive took 45 minutes each way, with three panels in the car each time, weighing about 30kg each. At approximately 200 kilograms in total, Gabrielle is literally monumental.

Only after weeks of this labour did the narrative sensibility of the work become clear. The final arrangement of panels shifted several times before settling into an order that felt right visually, emotionally, and rhythmically. Installed in sequence in the Parehuia studio, they still carried the faint scent of their burning in Papakura, a scent-line linking studio to home.

In Rani’s work, intense physicality becomes its own medium, a way of honouring lineage – in factories and plantations – while acknowledging emotional weight. He ‘paints from the shoulder’. Many pieces do not feel finished to him until they bear the marks of effort: worn surfaces, deep cuts, layers of soot, evidence of time. In Gabrielle, there’s a black beyond black, a vast space, a visual and emotional density that invites contemplation. The emotional heaviness of the six-panel work is imbued with personal loss. Before the residency, Rani and his partner had lost their Piha home in the cyclone for which the series is named. The carved-out apertures, the grids, the burnt voids hold echoes of collapse. Yet the panels do not read as ruins; they keep the tension of survival, of beginning again on uncertain ground.

These dark voids stem from multiple experiences. Rani recounts his time spent in monasteries in Tibet and the Himalayas, practising deep meditation, recalling memories of “dropping into the void,” moments when his ego dissolved. Such experiences of dissolution thread through the apertures and burned passages of Gabrielle, which also draw upon Mangaian adzes and their pierced forms, not as direct replicas but as echoes shaped by his upbringing in factories rather than plantations, by repeated labour rather than inherited ritual. As Cook Islands master carver Mitaera Ngatae Teatuakaro Michael Tavioni2018, 50 reminds us, “Polynesians were practicing abstraction, long before it was ‘discovered’ by the West.”

The voids are also suggestive of fecundity and can be easily read as one half of a primordial pairing, completed by another of Rani’s signatures: planes of protruding pegs. The connection is, in fact, more visceral: deliberately broken pegs are stark reminders of the great atua Tangaroa’s emasculation by missionaries; apertures are tiny windows onto Pacific peoples blackbirded and held in darkness below ships’ decks. There is a sense of his ‘re-membering’Tengan, 2008 Mangaian masculinities while recalling narratives of rupture and confinement, and a gesture toward histories and ancestral technologies whose residual presence lingers without binding him to their precise genealogies or village-specific lines.

Rani often speaks of the “scent” of history lingering within materials, describing an atmospheric archive, a sensorial trace of ancestral presence that guides, unsettles, and accompanies his making. Such a notion aligns closely with accounts of ancestral transmission, where knowledge flows not only from the past to the present but also back toward the ancestors and forward into yet-unrealised futures. This exchange is not unidirectional; we speak with our ancestors as much as we listen to them, contributing our own understandings to an ongoing lineage of thought. Such exchanges across time are part of an “eternal continuity of leadership,” accessed through tangible and intangible sites of oral history Kelly, Jackson and Hēnare 2014, 64; cf. Kelly and Nicholson 2021. Ngāti Porou Historian Nēpia Mahuika 2012, 4 has reflected on the songs and stories of his youth not as the words of a single speaker, but “generations of relatives weaving together an aural tapestry representative of our collective identity.” Rani’s work resonates with this mode of ancestral correspondence. His materials carry histories that are neither inert nor silent, and his process can be understood as a dialogue with those voices – a creative reciprocity in which the past is activated, the present reshaped, and the future invited into being.

Antidote

During the final weeks of the residency, Rani began working on a contrasting piece: a more painterly, hopeful work that he describes as “the antidote.” Created as a love letter to his partner, it gestures towards the future rather than the past. Painterly and bright, it draws on their shared experience of watching the Sky Tower’s New Year’s fireworks from the window of their new home in Papakura: small bursts of light across a distant skyline. Surfacing floral motifs and the bright colours usually hidden within his darker works, Rani allowed himself joy, playfulness, and a lighter touch.

Taken together, the Parehuia works – vast panels, paint-skins, and a series of smaller works on ply – confirm Rani as a maker of considerable generative power. They operate at an expanded scale: gathering communities of experience, memory, and affiliation around them, while remaining open enough to support multiple interpretive trajectories. Complexity science’s theory of boundary objects is apposite here, as it explains how material forms can create shared points of recognition. Leadership theorist James Hazy explains that such objects “allow those inside to identify those like them,” forming a boundary within which “‘we’ are empowered in concert” Hazy 2012, 224. Rani’s works also function in the Star and Griesemer (1989) sense, as forms that travel across multiple sites and carry differentiated meanings yet retain enough coherence, or “scent,” to translate between the disparate worlds of factory, studio, and ancestral inheritance that shape their making. Thus, Rani’s art does not merely depict belonging; it enacts it, functioning as a substrate for collective orientation and mutual recognition across cultural, temporal, and genealogical boundaries.

At the same time, Rani’s process exemplifies a mode of becoming rather than static being. He has spent considerable time practising deep meditation; dedicated 10,000 hours to a self-directed art apprenticeship, when his works were shown to no-one; and devoured the works and words of experts, so he can situate his work in various art histories and imagine it as readily in a contemporary gallery as in a Pacific collections wing, alongside carved forms and wrapped deities.

His iterative, process-oriented, future-focused practice encompasses the “multiple subjective experiences, and their accompanying diversity of interpretive, meaning-giving frameworks” that drive system transformation Allen, 2001. Anthropologist Tim Ingold’s theory of correspondence (2014) further frames Rani’s work as unfolding along “ever-extending ways,” where humans, materials, and environments are verbs – entities “in the throwing,” continuously emerging through relation. This movement resonates strongly with the relationality of the Moana Oceania cosmos, where becoming and belonging are mutually constitutive, and where the whole arises from the “interactions and relationships between the parts” Capra and Luisi 2014, 10.

Gathering horizons

Rani has a desire to touch the universe. During his residency, studio visitors often broke down in tears in relation to his work. If, he says, in five hundred years, someone might stand before the Gabrielle panels and feel that same pull of emotion, then the work will have succeeded in speaking across time, across cultures, across the distances between human experiences.

Samoan Professor Leali‘ifano Albert Refiti writes of artefacts in Oceania as “gatherers of horizons,” organising the world and drawing people into their luminous fields of mana. They hold past, present, and future in suspended relation, creating vā energetic fields through which multiple horizons can meet. In this sense, Rani’s works are not simply paintings or objects. They align with Refiti’s horizon gatherers – entities that draw disparate temporal and spatial fields into relation. Rani’s recursive residency, which joined the sites of Parehuia and Papakura, his lost home in Piha and ancestral connections to Mangaia, can be understood in these terms. Each place furnished a distinct horizon of force and meaning, now knotted into the evolving relational matrix of his practice. The results are vessels of labour and “scent,” marking boundaries and connections, gathering horizons and holding the potent residues of lineage, landscape, spiritual inquiry, and domestic rebuilding, while projecting them into the future.

Allen, P. 2001. “What is complexity science? Knowledge of the Limits to Knowledge.” Emergence: Complexity and Organization 3(1): 24–42.

Capra, F., and P. Luisi. (2014). The systems view of life: a unifying vision. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Hazy, J. (2012). “The unifying function of leadership: shaping identity ethics and the local rules of interaction.” International Journal of Systems Science 4 (3): 222–241.

Kelly, D., Jackson, B., & Hēnare, M. (2014). “He Apiti Hono, He Tātai Hono’: Ancestral leadership, cyclical learning and the eternal continuity of leadership’, in R. Westwood, G. Jack, F. R. Khan & M. Frenkel (Eds.), Core-periphery relations and Organisation Studies (pp. 164–184). Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kelly, D., & Nicholson, A. (2021). Ancestral leadership: Place-based intergenerational leadership. Leadership, 18(1), 140-161.

Mahuika, N. (2012). ‘Kōrero Tuku Iho’: Reconfiguring oral history and oral tradition. (Doctorate of Philosophy), The University of Waikato, New Zealand.

Refiti, L. A. L. (2023). Artifacts of relations and the gatherers of horizons. In M. Nuku, Oceania: The shape of time (pp. 12–13). The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Star, S.L. and J.R. Griesemer. (1989). “Institutional Ecology, `Translations’ and Boundary Objects: Amateurs and Professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907-39.” Social Studies of Science 19 (3), 387–420.

Tavioni, M. (2018). Tāura ki te Atua: The role of ‘akairo in Cook Islands art (Master’s thesis, Auckland University of Technology). Te Ipukarea – The National Māori Language Institute, Faculty of Culture and Society.

Tengan, T. P. K. (2008). Re-membering Panala‘au: Masculinities, Nation, and Empire in Hawai‘i and the Pacific. Special issue, The Contemporary Pacific 20 (1): 27-53.

Author bio: Dr Billie Lythberg is Associate Director of Juncture: Dialogues on Inclusive Capitalism at the University of Auckland Business School. Her art-based research focuses on Te Taiao—environmental and human systems of organisation in generative balance.

Artist Artworks

Sefton Rani

Abstract Tapa 3

2025

acrylic paint skins, acrylic enamel, acrylic polyurethane on Aluminium Composite Material

265 x 265mm

$1,500

Photo: Sam Hartnett

Sefton Rani

Abstract Tapa 1

2025

acrylic paint skins, acrylic enamel, acrylic polyurethane on Aluminium Composite Material

265 x 265mm

$1,500

Photo: Sam Hartnett

Contact us to purchase this edition.

Sefton Rani

Abstract Tapa 2

2025

acrylic paint skins, acrylic enamel, acrylic polyurethane on Aluminium Composite Material

265 x 265mm

Collection of McCahon House Trust

Photo: Sam Hartnett