- Amy Howden-Chapman2014

- Ana Iti2020

- Andrew McLeod2007

- Andy Leleisi’uao2010

- Anoushka Akel2024

- Ava Seymour2009

- Ayesha Green2022

- Ben Cauchi2011

- Benjamin Work2024

- Bepen Bhana2016

- Campbell Patterson2015

- Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss2021

- Dan Arps2014

- Daniel Malone2014

- Emily Karaka2021

- Emma Fitts2018

- Eve Armstrong2009

- Fiona Pardington2013

- Gavin Hipkins2007

- George Watson2024

- Glen Hayward2011

- Imogen Taylor2017

- James Robinson2007

- Jess Johnson2019

- Jim Speers2010

- Juanita McLauchlan2025

- Judy Millar2006

- Kathy Barry2012

- Lisa Reihana2009

- Liyen Chong2012

- Louise Menzies2016

- Luise Fong2008

- Madison Kelly2024

- Martin Basher2010

- Matthew Galloway2025

- Michael Stevenson2023

- Moniek Schrijer2021

- NELL2023

- Neke Moa2023

- Nicola Farquhar2018

- Oliver Perkins2017

- Owen Connors2023

- Regan Gentry2012

- Richard Frater2020

- Richard Lewer2008

- Rohan Wealleans2008

- Rowan Panther2025

- Ruth Buchanan2013

- Sarah Hudson2025

- Sarah Smuts-Kennedy2016

- Sefton Rani2025

- Sorawit Songsataya2018

- Steve Carr2020

- Suji Park2015

- Tanu Gago2022

- Taro Shinoda2017

- Tiffany Singh2013

- Tim Wagg2019

- Wayne Youle2019

- Zac Langdon-Pole2022

- Zena Elliott2026

Daniel Malone

YEAR OF RESIDENCY

November - February 2015

Malone works with all media including performance, sculpture, video, sound, painting, photography, graphic design, and ceramics. He works with spaces and objects to evoke situations that explore concepts of cultural identity and behaviour that provoke philosophical and political questions.

‘Depart the illustrious chiefs who have gone before … Go to that land from which no man has ever returned. […] The old order has changed: your ancestors said it would change. When the net is old and worn it is cast aside and the new net goes fishing.’

- Dr. Maui Pomare, speaking at the tangi for Te Whiti in 1907.1

I

Daniel Malone has the McCahon house residency, during which he has done some paintings that directly quote the work of Colin McCahon. We could say Malone (MaL) has a residency in McCahon (McC), and more, we could say that the relationship of McC to MaL presents us with a diagram of the relationship between then and now, between the modern and the postmodern (for want of a better word), between the historical and the contemporary. Anyway, I’m gunna say that. From McC to MaL, and yes, back again, because MaL’s work constructs a kind of feedback loop, beginning from McC’s paintings and indeed often seeming to copy them, but at the same time leading them astray, playing with them, actually taking the piss a bit, all in order to release their unknown pleasures, their hidden reserves that will prevent McC becoming just another case of Modernist DIE BACK.

All this is succinctly stated in the title to MaL’s show where all the works I will discuss appeared - I&I.2 In Rastafarianism I&I refers to the relationship between me and God, a kind of humble synthesis in which the parts are joined into what we might call a double-oneness. Anyway, I’m gunna call it that. Because if McC was the artist of the I then MaL is an artist of the double, of doubling, of I&I, of McC + MaL calculated as the equation in And per se And (2015) has it: 1+1=3. Added-value re-mix. I&I is a room of mirrors, a fractalised multiplication of references without end, an open complex surface. It’s compositional principle is the ‘and’, a gesture of contingency by which one becomes one more and the references accumulate. I is an Other. But that I is I, too, and you too my friend, and you. The existential angst animating McC’s subject, his search for meaning, his yearning for faith, all his singularity is repeated recursively, each part forcing the whole to shift, to wander, to replicate. To update.

It’s a short distance from McC’s old house in Titirangi to the new residency studio built next door, but in the architecture we see an enormous distance, an age between them, different times, different beliefs, a different world. MaL sits in that studio gazing into the sun-blasted Kauri bush as McC once did. Wondering what McC saw, wondering if that still has something to do with us. And so, respectfully enough, MaL paints some pretty nice and damn big paintings, large unstretched and unprimed canvases flexing with McC’s motifs, colours and …(shuffle)… stuff.

Stuff.

Stuff is that awkward thing - content. We will continue to come back to this question of stuff, to worry it like a scab, like McC continually circled his own existential angst. Pick, pick, pick. Because if there is what we could call “content” in MaL’s paintings it is precisely this question of the “like”. In what ways are MaL’s paintings like McC’s, and in what ways are they not? Some of them look quite like McC’s; the writing, the numbers, the Tau cross, the dicky Cubism, the terracotta and black. Some of them also engage with McC’s thematics; Christianity (one’s relationship with God, St. Francis), the glory of the South and regionalism in general, comics and popular culture, Kauri’s and French Bay, getting really pissed. On the surface MaL’s paintings are like McC’s, because today (and actually for quite some time now) both form and content are understood as surface effects.

No worries bro, we got them nice new nets

For an artist not known for painting, MaL painting all them Paintings is clearly quite a commitment. A qualified commitment. Because while McC is committed to his content (faith!), MaL quotes it, and in doing so, in qualifying it, he opens it out, releases The Bats, proliferates its possible references into Clouds (1975), into drifting cumulus whose shadows make flicker the constant flow of light.

Textuality baby.

The first axis of our McC-MaL diagram, the first ‘zone of contact’, is the pomo pleasure principle: commitment + quotation = qualified enjoyment.

II

Examples: McC’s Six Days in Nelson and Canterbury (1950) likens God’s creation of the world to McC’s creation of NZ, Christ’s sacrificial blood and suffering front and centre just like the artist’s. Needless to say: HEAVY SHIT. MaL’s Six Dais in Otago and Canterbury (2014), formatted like Six Days, gives us six clusters of bands from the Flying Nun and related underground rock scenes in Christchurch and Dunedin, more important to him in art school he says, than any painter or their work. A discography to MaL’s career as a cheeky delinquent. Or, more directly perhaps, whereas McC gives us the numbers 1-14 as the Stations of the Cross, MaL’s And per se And superimposes & (the ‘ampersand’), 0, 1, 3 and 8 in a multi-number, a numerical all at once. McCahon gives us AM I AM (Victory Over Death 2 (1970) - a gift to the Australian people about which Muldoon quipped; “I didn’t know we hated the Australians that much”) while MaL gives us the I&I of Rastafari, an apocryphal addition, a value-added (inhale) religion escaping the rules of sense. Cloak for Cleaner/Curator (2014) quotes McC’s great black and white checked jumper3 and wraps it around a Tau cross/broom, juxtaposing McC’s great artistic struggles with the forces of light and dark, good and evil, with the cleaner’s mod get-up. It’s a mod-mop. This work, while not really looking like a McC riffs on McC’s relaxed lean, that lean lean that combined formal strength and serious presence with a cool, louche charm. The man and the work. Today we are not surprised at all that an artist (or even a curator) should have to work as a cleaner in the ACAG, but we are absolutely amazed that this job was fulltime and led to McC becoming the deputy director! The old order has changed, and the old ways can no longer be understood…..

III

Before going further I want to immediately say that MaL is not just being an ironic prick. In fact I know he’d be the first one to middle finger those _____. He qualifies McC’s commitment with a loving humour (aye, bro), gentle and kind, a kind of stoned giggle, an Irie wander of body and mind. The very act of making such big paintings is already a homage, if not a pilgrimage (Ride Natty, Ride). In fact On the Use of Irony (2015) directly addresses this. The work reproduces the typography of McC’s I Am (1954) in an INRI sign, originally hung above Christ on the cross as an abbreviation for ‘Jesus of Nazarath, King of the Jews’. MaL hangs it the same angle as it appears in McC’s Crucifixion: the Apple Branch (1950). MaL told me;

As to IRONY, and I’m definitely not trying to be Ironic about any of this, an INRI painting I’ve made is about what to do with irony in all of this. Placed on the cross it was supposed to be an ironic sign of course, and thus was left in Christian iconography to signal its vindication as TRUTH. It then thus again functions as ironic.4

What are we to make of this? Irony too, like truth, is always qualified, a product of historical circumstance. One guy’s truth is another gal’s irony, and an irony turned truth is itself ironic. Only one conclusion is possible; irony evaporates in its ubiquity, it cannot exist when EVERYTHING IS IRONIC. There is no truth and no copy because everything is a copy of the truth. Even truth. Word!

IV

Nevertheless, You Must Face the Fact (1980-1) that painting today carries with it more than a whiff of historical redundancy. I mean, it is over-determined by an historical importance whose negation is a condition of almost all contemporary practice. Today, one must first address this fact if one is to paint, giving contemporary painting a kind of hyphenated existence qualifying (inoculating) its historical precedence (pretentiousness?). ‘Conceptual-painting’, painting as an element of mixedmedia practices, ‘painting-performance’, painting as collage, painting as a research based practice, etc.. This is no doubt a reason for the popularity of painting after photos, a simple gesture immediately qualifying painting’s claims to presence, grasping it within the safe and loving arms of inverted commas that turn it into a sign of itself, it’s “painting”… Of course, it is not as if painting has not faced this challenge before, and Modernism can be understood as painting’s efforts to escape its own historical determination as representation. The various movements defining Modernism - towards abstraction, towards popular culture and the everyday, towards political engagement - can all be understood in this way, and all are (more or less) parts of McC’s and subsequently MaL’s work. But in different ways of course.

We could put it more simply and just say that McC - pheeuwieeee - he really took that shit serious. For McC being an artist, a MODERN artist, meant expressing himself, himself qua unique individual with his own unique vision, expressing his _______ prophetic shit. For MaL the personal is already qualified, or perhaps better, constructed. The POST-MODERN artist is a tissue of quotations (Barthes), and art a process of post-production (Bourriaud), the artist is a cultural DJ spinning disks. Even - or maybe especially - when he’s “painting”.

V

McC’s abstraction was a means to explore the sensation of forces that go beyond the limits of representation, whereas for MaL it is a “sign” of that. If it is possible to still see the heads and shoulders of the fishermen in the black and red blocks of McC’s Flounder Fishing, Night, French Bay (1956-7), then it is only because these blocks interrupt the scintillating moonlight as an analogical expression of the differential force (abstract but actual) of fisherman-moonlight. No metaphor, no ‘image’. The economy of representation is quite other, being based on a system of negative differences (not that) forming ‘signs’ with no material relation to their ‘original’. Signifier and signified, and never the twain shall meet! It is this constitutive but nevertheless negative difference animating signs that enables MaL to launch his often hilarious McC mash-up. In Arhythmia (2014) for example, the terracotta and black references McC’s Necessary Protection paintings from the ‘70s, whereas the composition references, funnily enough, Flounder Fishing, Night, French Bay.

We might immediately object that McC’s painting does this too, clearly referencing Milan Mrkusich’s City Lights from the year before. No doubt McC was entirely self-conscious in his use of Mrkusich, and his reinterpretation of City Lights as Flounder Fishing knowingly recasts its sophisticated abstraction in a local and distinctly ‘country-hick’ dialect. (I mean, mate, we’re going flounder fishing and we’re gunna get soooo pissed on the Lion Red!) We see the difference immediately; one is smooth the other awkward, one is stylishly coloured the other brooding and dark, and McC’s is locally specific while Mrkusich’s is internationally generic (but good I hasten to add, real good!). In McC abstraction dissolves representation, a process that is foregrounded by representation always retaining a presence - usually as landscape - and thereby anchoring abstraction to this place, while in Mrkusich abstraction proclaims its international ubiquity - even in NZ - as a nonrepresentational, modern urbanity embracing the globe, and Mrkusich with it. In this sense, McC uses abstraction to explore his own commitments, which always remain recognisable, consistent and completely rooted in NZ. Mrkusich uses abstraction as the self-evident sign of a global culture that includes NZ, but only in the sense that it also erases it.5

VI

Today the Modernist opposition of regional-international has been sublated in the univocal quotationalism of the post-modern, and the univocal commodification of late capitalism. This is a point made by the collection of labels in Cloak III (The Wretched of the Earth) (2014), the ‘local’ of a multi-national brand is where its made - Made in Romania. A place of exploitation and brutal work. Along with the poverty of St. Francis (Cloak II (Do you feel me St. Francis? (2014)) and the curator/cleaner of Cloak I these works evoke the ‘people’, the poor, the wretched workers from which global capital reaps its profits. Apart perhaps from the factory and prison of Imprisonment and Reprieve (1978-9) and its plaintive cry ‘you too my friend, you too, and you’ McC’s work does not approach the workers en mass. For McC solidarity is found in faith and death, and these are the basis of his quite nihilist ‘politics’; ‘Everything that confronts him, everything is empty since one and the same fate befalls every one. Just and unjust alike, good and bad, clean and unclean.’ (I applied my mind (1980-2)) We can only hope class is banished in the afterlife, McC never quotes the Commie bits of the bible, the last is first and all that. In any case, today the political realm is no longer ordered according to here and there, centre and periphery, regional and international(e) because everywhere is everywhere and the only question left is what its worth. Can you sell your shit? So while on a formal level MaL may very well quote McC like McC quotes Mrkusich, the nature of this operation is irrevocably transformed because its original reference points no longer exist. Distance no longer looks our way, there is no outside, and a univocal cheap glamour (H&M) simply slimes along the surface of things following the path of least resistance. We all dress the same and difference is only relative. But it’s all good. Of course. McC, his dress sense aside, was curmudgeonly, belligerent, he deliberately rubs Mrkusich the wrong way, and Flounder Fishing delivers both a correction and a telling off. Just like Kaipara Flat No. 8, An Appreciation of Gordon Walters (1971) where the signature koru is redone as defaced script, in Pound’s words, its ‘turned into a cloudscape’! 6

MaL whispers sweet nothings in McC’s ear, feeds him some drinks, gets him loose and comfy so they can, like, ‘see what happens’….. Charms the pants. When McC “references” Mrkusich - when he, quote-unquote “quotes” him - he does so in the name of his own commitments, and in order to start a fight. MaL wants to subvert those commitments, to set them free in the world so they can get busy and creative. So they can collaborate. As MaL himself puts it, his engagement with McC is

a kind of open process, an experiment to see where I end up, what with, now, here. So I think to be honest while there is a taking stock it is without any clear destination let alone agenda (save maybe a slowly accrued sense that McC had been sold short in the delimited process of the canonization he finally received or perhaps rather I’d been sold short in what had been offered to me of his work – a hunch coming here seemed a good moment to act on.7

Another example is McC’s endless quotation of the bible. And he really does quote it, he writes it out, often quite literally, on a school blackboard. The school-ma’amy tone is unmistakable, it’s a preach. But what is important for us is that by writing it out (as opposed say, to illustrating it) McC points to the operation of quotation, foregrounds it. But he does so not to lose himself in the word, but rather the opposite, to appropriate the power of the word for his own artistic mission, to take on the power of God’s voice. In this sense, Pound writes, McC’s paintings not only harmonise their various references (‘I’ is also ‘1’, etc.), but sing with a single voice, inasmuch as they are all imbued by McC’s touch with the unmissable signs of his self.8 A kind of autobiographical ecumenicism: HIS handwriting, HIS bible, HIS NZ, HIS Maoritanga, HIS abstraction, HIS poems, HIS Mondrian, HIS kumura patch, etc.

VII

In fact, this might describe the way in which McC uses found materials. I deliberately say ‘materials’ here, because McC “finds”, in a very contemporary way, both material objects (house paints, the mixing of sand into the paint, wallpaper, blinds, unprimed canvas) and symbolic ones - language and images. Indeed, this is perhaps the most contemporary aspect of his work, the way he took existing written and visual material and used it in his work. The list of these operations spans his entire oeuvre, and is the foundation of his method. Most obviously, the bible (words and image), but as well, modernist abstraction, comic books, Maori history, mythology and language, Malevich, roadside signs, sign-writing, On the Road (1976), Moby Dick, Caltex (1965), the drawings in Cotton’s Geomorphology or those of Charles Heaphy, popular songs (Now is the Hour (1962)), noughts and crosses, Martin Buber, Renaissance painting (Entombment After Titian (1946)), the Italian ‘Primitives’, the list is endless. And true to the very democratic nature of this practice, it rubbed his work right into popular culture, a fact that caused scandal at the time. Just before McC’s 1947 show of biblical scenes painted like comics, a bill had been moved, but not passed, to ban comic books. ‘Celestial graffiti’ Fairburn called the paintings, half in horror, half in encouragement. This high/low mix still feels cool. The ‘comic’ paintings of ‘47 are, in one sense, as far away from Pop as you can get, but in another they prefigure it. I’m not trying to hedge my bets, I just want to point out two different historical perspectives. On the one hand those paintings are about spreading the word, about setting it down right there, right then and humble as hell, God speaks to us in comics: Crucifixion according to St. Mark (1947), The King of the Jews (1947), The Promised Land (1948 - Farewell Spit front and centre, with Moses/McC sunburnt and in a black shearing singlet to the left - G’day mate!). This is the most appealing aspect of McC’s Christianity, its mundanity, its everyman appeal, its poverty and simple beauty. Everything gets so inflated in the later written-out-bible works, and not just the scale. You have to read so much, you have to understand something about modern art, and their dominant theme is an egotistical personal doubt. McC convincing himself. On the other hand the comic paintings are bright and colourful, accessible and open to the world - Pop art. While referring to the anti-comics law is kind of old-school art historical, locating the work in its context, claiming the work is proto-Pop is new age “theory” (i.e., dizzy and misguided, but on the surface of things, yeah, why not?). More generously, to see Pop in McC’s comic paintings is a reading done, shall we say, with the benefit of hindsight. But, and as such, it is a reading that slides down the surface of things, moving from sign to sign, from reference to reference. It makes historical work contemporary, and as art history its weak but as art, hey, it works! In fact, MaL’s point is even more vigorous, more ontological, because quotation is not a ‘mode’ of reading, it is an epistemological fact; our world is a hypertext, unfolding moments of synchronicity, the mother-fucking network. Everything is a link. Something to like. In MaL’s work, it’s not that I&I (2014), or Cloak III (as the most obvious examples) are particularly Pop, it’s that they exemplify the fact that today everything is already an ‘info-commodity’, a freewheelin’ sign for itself, or maybe (who knows?) for what it’s not. The work of art in the age of digital reproduction is a process of repetition distributing signs along a trajectory of ramifying difference. Art=Life. To get back on point: MaL’s work and McC’s share some formal aspects, some techniques, some content, but they are nevertheless generated out of an entirely different historico-political context. That sounds like a wank. What I mean is that McC and MaL are producing work under quite different assumptions as to what constitutes ‘art’.

VIII

It seems to me that MaL’s work embraces and emphasises the element of ‘appropriation’ in McC’s work, which we could say simply extends McC’s method into a more contemporary context. But we won’t.9 Because if we did we would just casually obscure the differences, collapse them into an empty affirmation of reference for its own sake. MaL’s paintings do nothing if they do not insist upon the monumental modern/post-modern shift in the concept of the artist. McCahon’s appropriation could be incredibly direct - just write out someone’s poem (Peter Hooper, John Caselberg, Matire Kereama) on wallpaper or canvas - but at the same time because McC’s “style” was so singular and recognisable, this act also totally changed the words he took.10 They became HIS, undoubtedly and immediately, because appropriation was never intended by McC as an interrogation of authorship. For us, the idea that there is no original because there are only copies is the most common blasé fact (Art Theory 101, but actually it’s just a simple fact of life). McC is the exact opposite of this, he takes one original and makes it into another - THERE IS NO COPY. Today, this remark can only exist as a description of an entirely historical fact. THERE IS NO COPY. Put that in your Zig-Zag and smoke it!

Today, questioning the authority of authorship through an act of quotation or appropriation has become part of the gesture of appropriation itself, as it is in MaL’s work (for example his Black Market Next To My Name (2008), a work that succeeded in selling the contents of his flat as a ‘found object’ art work). In this sense, MaL’s ‘appropriation’ of McC’s style locates it within a collection of other references and techniques (most obviously that of the found object) none of which belong to MaL qua original or originating subjectivity. MaL is a contemporary artistic subjectivity, composed of a tissue of quotations of which “the artist” is one. MaL takes McC’s style as a found object, not a neutral one certainly - it is no pure readymade qua ‘any-object-whatever’ - because MaL uses it to express quite specific, and often very personal things (rather than interrogating the epistemological conditions of art or…. yawn). But nevertheless, MaL does not ‘translate’ McC into his own style in the same way that McC did his own ‘texts’. Rather, MaL’s paintings invite us into the gap, the irrevocable chasm separating MaL and McC, separating I&I, separating McC’s house and the studio out back. There’s no going back.

IX

MaL <> McC, a movement somewhere between going and coming back, between carrying on and giving up, between four to the floor and dub-step. Between The Gordons and The Rip: A Trapdoor Exit? Arhythmia, stuttering, lurking down the back. Not knowing what I want, not knowing what I’m talking about. Arhythmia (2014) (everything I say here under the condition of not having actually seen it) - an act of translation? A movement of transition? Just doing the commute? Between times, between continents, between then and now, MaL and McC, here and there, him and me, modernism and postmodernism, you and I, I and Thou, similar and different. NZ and the world, staying home and going out. Taking pills and smoking pot. And back to the found object. Arhythmia is analogue personal inasmuch as the empty pill packets are documentary evidence of MaL’s arhythmia, but like documentary evidence they are also rather neutral and objective, detached, medically defining a generic set. They indicate that MaL belongs to the set of people with arhythmia. Nothing more or less, the packets are a physical residue of a physical problem and its solution (physical). But this process (of taking pills and of the physiological correction they make) is - in the work - transformed by a practice. MaL qua generic set is juxtaposed with the McCahonesque. MaL qua medical subject swims in the black waters of the Manukau, following the Titirangi tide marks, looting the washed-up detritus (French Bay Landscape (2015)). Schwimmen In Der See. The generic pill packet, a psychologically blank but nevertheless analogue sign for MaL (himself an empty or shifting [shifty?] signifier) acts as a quotation of McC. Spanning these two things, between a generic set and the actual body it conditions - it cures - lies the postmodern subject. (“Are you on facebook?”) A body whose soul is constituted by the cloak of quotations that covers it: Zig-Zag Man, ‘Oh Charley Brown’, McC’s Mapua Landscape (c. 1940-1) … Arhythmia contains other signs of McC; the calligraphic gulls, the mosaic tiles of Flounder Fishing Night, French Bay, the relaxed gravity of the hanging canvas. They form the background murmur of the painting, signifying, at least for those of us of a certain age (MaL, b. 1970), our inheritance, our father’s presence. These unmissable signs of McC’s work, these trademarks, what is their status here, within this text (without text)? Do they retain an otherness, a modernity, a stubborn individuality? Or are they assimilated, appropriated, consumed in a process, becoming what we might call, in short-hand, a (generic) ‘found-object’? If so, then these signs would be typical of how found objects tend to be used in ‘contemporary practice’, their status as everyday objects opens art onto the world, allowing it to move unhindered by its history or intent (i.e., in exactly the opposite way to McC). In this sense, quotation is one way in which contemporary artistic practice enjoys - indeed insists upon - its non-art status, surfing the infinity of signs constituting the www of information, our very own plane of immanence (yeah man, ;-)). Quotation is the democratisation of art, we’re all doing it. Nietzsche said we should all become poets of our own lives, but I don’t think that quotation was what he meant. McC wasn’t a poet, he was a _____________ Original-Artist. He roll like dat.

Today, we <3 fluid identities and shifting forms, we (y) transient facts. We dance amongst the generic signs, consume them, photoshop them, send them to our mailing lists. We use them to endlessly talk about our “selves” (cognitive capitalism=endless self-expression), even if just to say WE ARE NOT THAT, we are of course, MORE THAN THAT, the delirious narcissism of the AND… We are the AND per se.

And yet. MaL’s quotation of McC, his appropriation of McC, does not abandon the frame of painting but rather embraces it. So while Arhythmia actualises the distance between MaL and McC, it does so in paint, utilising McC’s vocabulary to bridge the chasm, to lead McC across. To us. Batting the eyelids, come-hither looks. Conjunction: anyone familiar with McC will recognise his loved colour combination of terracotta and black. Disjunction: between the pills and the canvas lies the chasm between modernist painting and contemporary practice. What does this mean, more exactly? That MaL’s method of composition is not McC’s, whose found ‘material’ was always presented in his own style. He took ownership of it. The pills (qua personal signifier) are not MaL’s in this way, MaL does not own them, he takes them, which is perhaps a succinct description of the conjunction/disjunction I’m trying to get at here….. McC’s signs started out someone else’s but he transformed them into himself. MaL’s signs are generic (pills and paintings), juxtapositional, recombinable, flexible, meaning McC’s McC and MaL’s “McC” are not the same fella, and when MaL takes McC (like a pill, or perhaps from behind - giving him a mutant child) he transforms him into something else.

And yet. And yet the painting remains, McC’s voice sounds out, and the ventriloquism of Arythmia seems more tragedy than farce, which is how McC would have liked it.

X

What I want to say, it’s been said before, more beautifully and correct. Ralph Paine has produced the single best book on McC, ever, and he writes:

Our task: to take possession of McCahon’s effects within the world - the traces of his moods - to use them against themselves, as a resistance to their own time, their own present, in order to turn them into a new cause; to take back his Proper Name, and hence his multiplicity rather than any bounded oneness, from those who would use it to block our becoming.11

My question here is simply if that is what McC would want? But maybe this question isn’t really relevant.

XI ‘Our becoming’, MaL and McC’s, the alpha and omega. Omega and Alpha (Kauri, Unfinished) (2015), let’s track its becoming, lets follow its rhizomatic growth. MaL collected amber necklaces from flea markets in Poland, which, he told me, are often used as ‘votives, hung by people around holy pictures’.12 But as well, they look like Kauri gum, polished and made precious by Dalmatian people in Auckland, an echo of home, a shared religious effluence. The flow of people, of things, of a sticky substance congealing somewhere else, something MaL ‘gleans and reconfigures to conflate ecological and religious narratives of renewal and transformation through natural cycles’, as the room-sheet for I&I tells us. I think this is maybe what I already said… well maybe not the ‘natural cycles’ part.

These amber beads hang in the lower third of the painting over MaL’s generic reconstruction of McC’s Kauri paintings - a reconstruction closer to the central part of McC’s Kauri Trees (1954) than the painting quoted in MaL’s title. Kauri, Unfinished (1953) however, has the advantage of showing two houses prophetically configured like McC’s Titirangi cottage and the residency studio built next to it. That’s weird. On the floor below the painting are the words ‘DIE BACK’, the term used to describe the Kauri’s gradual disappearance in Titirangi, but which MaL also seems to apply to McC’s status as a “living” artist. Following the trail we find Gordon Brown’s words on these works:

Such pictorial leap-frogging makes it difficult to discuss the work McCahon produced during his Titirangi years as if it progressed in a neat orderly fashion, with one group or series necessarily following the other. While there is stylistic development in his work from this period, certain factors appear, submerge and reappear, while other divergent factors are simultaneously worked upon. Some effort is required to avoid oversimplifying a sense of order in this apparent maze.13

Let’s pick that up and run with it. Into the maze, into the haze, into the Titirangi bush.

The middle third of the painting shows an alpha sign inside that for omega. A comic book thought bubble tells us ‘This is the tomb’ (omega), while a speech bubble announces ‘This is the stone’ (alpha). The new covers the old, or more exactly sits snuggly inside it. The tomb and the stone echo the composition of McC’s The Marys at the Tomb (1950), but whereas in McC’s painting the stone has rolled back to reveal the empty tomb, and so Christ’s resurrection, in Omega and Alpha (Kauri, Unfinished) the stone remains in place, rewinding the narrative thrust of McC’s painting (emphasised by the angel dramatically pointing his hand out of frame - exit stage right) back to Christ dead. Rewinding, perhaps, back to McC’s pre-apotheosised state? Not to deny the resurrection, but just to replay it again in a more contemporary context (as the comic script suggests, a fact not lost on McC who also tried it). The alpha and the omega, the stone and the tomb, and MaL bringing McC back from the dead. Who needs God when you can be resurrected in a quote, reanimated more or less out of context? An afterlife of new signs that the artist (either one, both) is, indeed, present? MaL has returned home bringing evidence that McC was in fact Polish.

In the top third of the painting the hanging amber votive is repeated in a curve of hanging dots that is an obvious reference to a series of five paintings McC produced in 1974 called Rosegarden. For Brown these are ‘a half-circular string of beads, a half-ring of roses, possibly an adornment celebrating the sun.’14 Amber symbolises solar energy and supposedly transmits its warmth. But have you ever seen the sun in a McC painting? In any case, the beads were a motif McC also used as a part of other series of this time such as Angels and Bed (also referenced in MaL’s Six Dais in Otago and Canturbury) and the Muriwai paintings. Brown claims the title is from ‘the popular song of the period’ I Never Promised You a Rosegarden (which is basically a song about ‘tough shit….deal with it’, a truly McCahonian tune), but another story - one I like more - is that McC ripped that _____ off the Polynesians. Wandering around Grey Lynn, so the story goes, McC (probably pissed) liked to look in house windows (scary thought!). Looking into a Poly living room he saw family photos on the wall draped in leis. Polynesian decoration of the dead. The lightbulb goes off: that’s some totally cool shit! Brown, more seriously, goes on to quote McC’s old mate John Caselberg on these paintings, who claims the motif ‘describes suffering, particularly by Polynesian people, in Auckland. On a black canvas hangs a necklet of small roses or jewels: islands of light shining against almost unimaginable loss and pain.’15 Yeah, an almost Catholic vibe, something perhaps a little Polish? John Caselberg was a political militant, a very interesting figure, not only for McC but as one of the leading white liberals of the 60s who really wanted to engage with that BLACK POWER stuff.

Stuff.

XII In 1962 McC was involved in Caselberg’s reading of his play Duatterra King at the ACAG. The play was about Samuel Marsden and the New Zealand government’s confiscation of Maori land in direct contravention of the Treaty of Waitangi, and according to a review of the time it aimed at ‘stinging the social conscience’.16 Caselberg also edited the book Maori is my Name in 1975, which collected translated and incendiary Maori texts, including the one used as an epitaph for this text: ‘The old order has changed: your ancestors said it would change. When the net is old and worn it is cast aside and the new net goes fishing.’ Cut to Arhythmia, does it show the fish or the net? In any case Omega and Alpha (Kauri, Unfinished) is a new net cast from here to there, from MaL to McC, from Poland to NZ, from the Islands to Grey Lynn, from Modernism to the postmodern.

And what does it catch? Wrong question. Because this net, it sets things free. It catches the past in pieces, recombines them, mazes them, makes them new. A chaos-sieve,17 a ‘genealogy’ as Foucault called it, one that creates ‘virtual fractures’ within our present conditions of possibility or ‘historical a prioris’ in order to produce spaces of ‘concrete freedom, that is, of possible transformation’.18 Foucault says this in praise of Modernism, and Pomare, in 1907, said as much. Haulin’ on his new net, what does MaL set free? We’ll come back to that.

XIII

First, the whole MASSIVE question about McC’s biculturalism …. do we want to go there? We gone there.19 MaL is obviously down with those Rastafarians and all, Mr Zig-Zag Man, feelin’ Irie with the twelve tribes, rollin’ up some spliffs and listenin’ to Bob.20 Summer sunday afternoons in Aotearoa. I can feel it. But the Zig-Zag Man (I&I (2014)) takes us far away from McC because its only real echo is the paint direct on canvas. What is even further away from McC is the work’s humour, the wit of the deconstructive gesture that lays bare the process of a common object’s transformation into art, and of course (a necessary part of the wit) the suggestion that those dopey, daggy kids who drew on their bags were also “artists” in this sense. Them kids was us?! We find here another version of the MaL-McC conjunction/disjunction, only now in relation to the problems of biculturalism. These are of course MaL’s problems just as much as they are McC’s, but their respective answers are structured according to entirely different theoretical and artistic diagrams. In many ways MaL’s older work with tagging (vestiges of which appear in Omega and Alpha (Kauri, Unfinished) and Our Great O.E.’s (2015)) put his colours on the wall, because like the Rasta stuff - more stuff - it engages a certain (black) street culture under the assumption that within the conditions of late-capital all signs are available to be used, abused and most of all consumed. That’s a part of the new net capitalism likes, the way it can leverage race for profit. Yeah, and that’s something about contemporary NZ too, the way that Maori “signs” are now signifiers for ALL NZ, for WE (whoever), and no more anxiety about that COZ WE PAID THOSE _______ OFF, they got their swag. We bought out their shit, and now we can all break ourselves off a little action.

You get the feeling McC didn’t break himself off a little sumthin’ too much. But I guess we’ll never know for sure. What is for sure is that all the doubts, all the anxiety, all the AM I AM and the stinging social conscience pervaded his greatest work on biculturalism, the Urewera Mural (1975). A great story from beginning to end, incredibly fascinating, someone should write the book. What always struck me, sort of stuck in my throat, was the story of McC meeting with Tuhoe elders to discuss the Maori content of the painting. There was stuff they wanted him to change. McC agonised about this - there are angst-full letters to Caselberg - before deciding, ____ it, I’m the ______-_______ artist here and I decide what goes in my painting or not. Yeah mon. And I hesitate before saying this, but I’m going to suck up my courage and just say it, HE WAS RIGHT! Maybe he got the Maori stuff wrong, maybe his vision of an ecumenical Christianity as the universal basis of bicultural communication (the Tau cross front and centre is labelled Tane, God/Kumara patch, same difference) was dumb, but all that was what allowed him to get that painting so _______ right, because that painting rocks 100%. That painting is our (us whiteys) most valuable document (no, more than a document, a kind of living palimpsest) of bicultural relations in Aotearoa. That painting is about wanting a way forward, a conversation both angry and scared (AM I Scared Boy (EH) (1976)), but where the interlocutors are committed. And the result was a painting that carried on the conversation past McC’s death, a painting that is saturated in blood and tears and crazy ______ with guns going _______ bush. And coming back and playing the media, and being all clever and shit, and then going off to make love to _____ _____ on a Fijian beach. My name is Maori. My name is legion. And you better watch out for my ______-_______ new net you white honky bastards, ‘coz that net, you damn well forced me to take it off the end of your gun … and who’s laughing now? That painting has history carved into its flesh, and McC may not come out of it smelling good, and actually after about 1975 you gotta think he don’t smell too good, but you have to give him respect. He didn’t know what he was doing, but his stubborn ignorance was the most honest intelligence a white painter could offer. The Urewera Mural is so generous, so successful in a wider political sense, because of its commitment to saying what it meant, to having a vision. And let’s face it, the history of biculturalism in NZ is not exactly blessed with white fellas saying what they mean while treating the others as equals. So it led to a fight, nothin’ wrong with that, especially when the cuzzies done won it!

That McC considered himself equal to Maori is really important if we are to understand the nature of McC’s “regionalism”. For McC there was nothing problematic in saying that when he went on deck and saw the old Maori woman crying when she saw the first signs of Aotearoa - HE FELT LIKE THAT TOO. Just as there was no problem in saying: when you read The Shining Cuckoo (1974), read the words aloud, because then you hear the bird song that the Maori words also couldn’t capture. We’re like them, McC says, we don’t understand shit too, and like them this is the source of our most beautiful art! Analogue cultural politics - some kind of voodoo cultural materialism, possessed by the cuckoo and speaking in chirps..… Words (images?) are all the same, fumblings in the dark in search of otherness. Do you hear me St. Francis? So when McC dredges American post-war abstraction and dumps the lumps back into that poor NZ landscape ‘with too few lovers’ (The Northland Panels (1958)) he’s not “appropriating” nothing, he’s staking out Modernism in NZ with his name on it. Taking possession of it, he owns that shit. And he was fucking right. Use it or lose it baby. Like when he decides not to take the Tuhoe kaumatuas advice for the Urewera Mural, not disrespectin’ but just, well shit, I got my ideas too mate. We don’t know this form of commitment any more, we don’t have the simple guts, no wonder, today it no longer has the conditions by which it might exist.

So, to get back on point, MaL stages the MaL-McC disjunction/connection no doubt, with joy and beauty and sensual laughter. But the (conceptual) condition of this confrontation is that both its terms are as simulacral as the other, signs for a meaning, for stuff, both simply signifiers that refer to other signifiers ad infinitum. And the gambit is that this loving caress takes us out to we know not where, to another French Bay, to the Polish Kauri tree, to McC rolling joints and singing praises to Jah. Jump? Narratives weaving in and out of the actual and the invented, narratives that constitute a new New World. What the new net sets free….

And the gambit is that this question must be, can only be, answered by you, each time again, as another tumbling piece of our kaleidoscopic future. The prophet is dead and all that’s left is to reshuffle the pieces, to make it up as we’re going along. Like me. Obviously

XIV

Don’t get me wrong, I ain’t for no old and scabby nets.

But there was something in Modernism that was new, I mean the net was really new, not some slimy pomo “new”, and it released an unknown but utopian future that couldn’t be imagined because it was the irruption of the undetermined itself. Ungoogleable. And this ignorance was bliss, because it was the beginning of something better, of something else. We could not read it in the tea leaves of the past, we could not quote it, because it hadn’t happened yet. All we could do was find new weapons to win the old fights, weapons invented by us, by artists, by visionaries and all those who were up for it. It was the mother-_______ revolution. And it still is. As Foucault puts it, and I love his deadpan schtick, Modernism is about discovering ‘how that which is might no longer be what it is’.21 To make it new, to unleash something inhuman and dark and alive and brutally tough. Something REAL. SOMETHING REAL, without irony or melancholy or bored feigned interest. Something committed, something that couldn’t be thought, couldn’t be said, something that could only be forged from the pulsing vitality of what has not been, reaching past us to remake the earth. McC called it “God”, but what we see now is the force that came through his hands and into his paint. That’s our inheritance. MaL is a new net, no doubt. And he’s dipped it in the sparkling waters of McC’s French Bay, he’s walked amongst McC’s Kauris, now dying in the Titirangi bush. He’s slept out there, by McC’s old house, and listened to the tuis and fantails and wind in the trees and surf on the beach. He’s checked out McC’s shit. And you better believe it, it’s ALL good. And he’s produced a value-added re-mix. It’s arhythmical reggae beat breezes by, seducing your hips, skanking out a flip-flop roll that makes your arse go all expressive. Your at home baby. It’s good to enjoy it.

Looking out on the Pacific, the world, this ______-up life. Towards a multitude of McC’s? Towards a Promised Land?

Yeah, and other stuff.

Essay commissioned by the McCahon House Trust on the occasion of Daniel Malone's residency and resulting exhibition Titirangi Apocrypha, 20 February – 29 March 2015, at Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery

- Included in Maori is my Name, Historical Maori Writings in Translation, edited by John Caselberg (John McIndoe, 1976), p. 146.

- Daniel Malone, I&I, 29 January - 28 February, Hopkinson Mossman Gallery, Auckland, NZ.

- Seen on the cover of Gordon Brown’s Towards A Promised Land, On the life and art of Colin McCahon (Auckland University Press, 2010). On p. 98 you can see McC (in the same jumper) smile! Needless to say, it’s less than convincing….

- Personal correspondence.

- See Francis Pound, The Invention of New Zealand, Art and National Identity 1930-1970 (Auckland University Press, 2009), p. 230-1 for a rather more condensed discussion of these paintings. Pound also usefully notes that the work the McCs bought on their famous US trip and then presented to the ACAG on their return, Karl Kasten’s Fragment of Autumn, was representative of a West Coast Abstract Expressionism in which ‘regional figurative and atmospheric elements are used’. One could say the same for Flounder Fishing in its relation to Cubism and Mondrian.

- Pound, The Invention of New Zealand, p. 323. As with Mrkusich then, McC takes Walter’s international abstraction and turns it into this-place-right-here, HIS NZ landscape. In this context, the fact he erases what is most local about Walter’s work - its Maori motifs - must be seen as an extension of his critique.

- Personal correspondence.

- Francis Pound, The Invention of New Zealand, Art and National Identity 1930-1970, p. 140.

- Francis Pound, in a wonderfully irate passage to which I give the thumbs up, rails against those (primarily Wystan Curnow) who read McC as a proto-post-modernist: ‘This will not do. It is only to form McCahon, as it were, after the fashion of ourselves, that he might answer without difference or difficulty, to the postNationalist time. To claim McCahon uses biblical language only as a post-modernist might - arbitrarily, detachedly or critically - is not only to undo his difference, his strangeness, the very eccentricity of his place in the larger international modernist endeavour: it is also to reconstitute him, in a more palatable form, for a largely post-Christian age.’ (The Invention of New Zealand, Art and National Identity 1930-1970, p. 143)

- On this point Gordon Brown gets it right: ‘while such borrowings are evident in McCahon’s work, he never allowed these to swamp his own presence. The appropriated stylistic features are not wholly of the style itself, but features used to achieve a given end. What persistently co-exists is a range of identifiable shapes, irrepressible motifs, compositional devices and a control of tonality that characterise McCahon’s presence in much the same way as a personal signature or fingerprint. […] By such means, the artist’s own heartbeat resides in his work, notwithstanding the adoption of any foreign idiom.’ Towards A Promised Land, On the life and art of Colin McCahon, p. 17.

- Ralph Paine, Terminus Hotel (Teststrip, 2001), p. 6. I have to mention here - circles within circles, iron sharpening iron - Make History Poverty, Paine’s collaborative show with MaL at Gambia Castle (2008), which is some totally amazing shit.

- Personal correspondence

- Gordon Brown, Colin McCahon: Artist (Reed, new edition 1993) p. 52.

- Op cit, p. 180.

- Ibid.

- Quoted in Brown, Towards A Promised Land, On the life and art of Colin McCahon, p. 75.

- ‘Chaos-sieve’ is the title of a beautiful painting by Ralph Paine.

- Michel Foucault, ‘Structuralism and Poststructuralism’, in Aesthetics, Essential works vol. 2 (Penguin, 1998), p. 450.

- I wrote something serious about that; ‘McCahon’s Promised Land: The Politics and Aesthetics of Bicultural Mistranslation’, in Landfall 211, Autumn 2006.

- And not just Bob Marley, according to Ralph Paine’s and John Hurrell’s interesting exchange about I&I on the Eyecontact website. http://eyecontactsite.com/2015/02/daniel-malones-titirangi-paintings

- Foucault, ‘Structuralism and Poststructuralism’ in Aesthetics, Essential works vol. 2, p. 450.

Artist Artworks

Daniel Malone

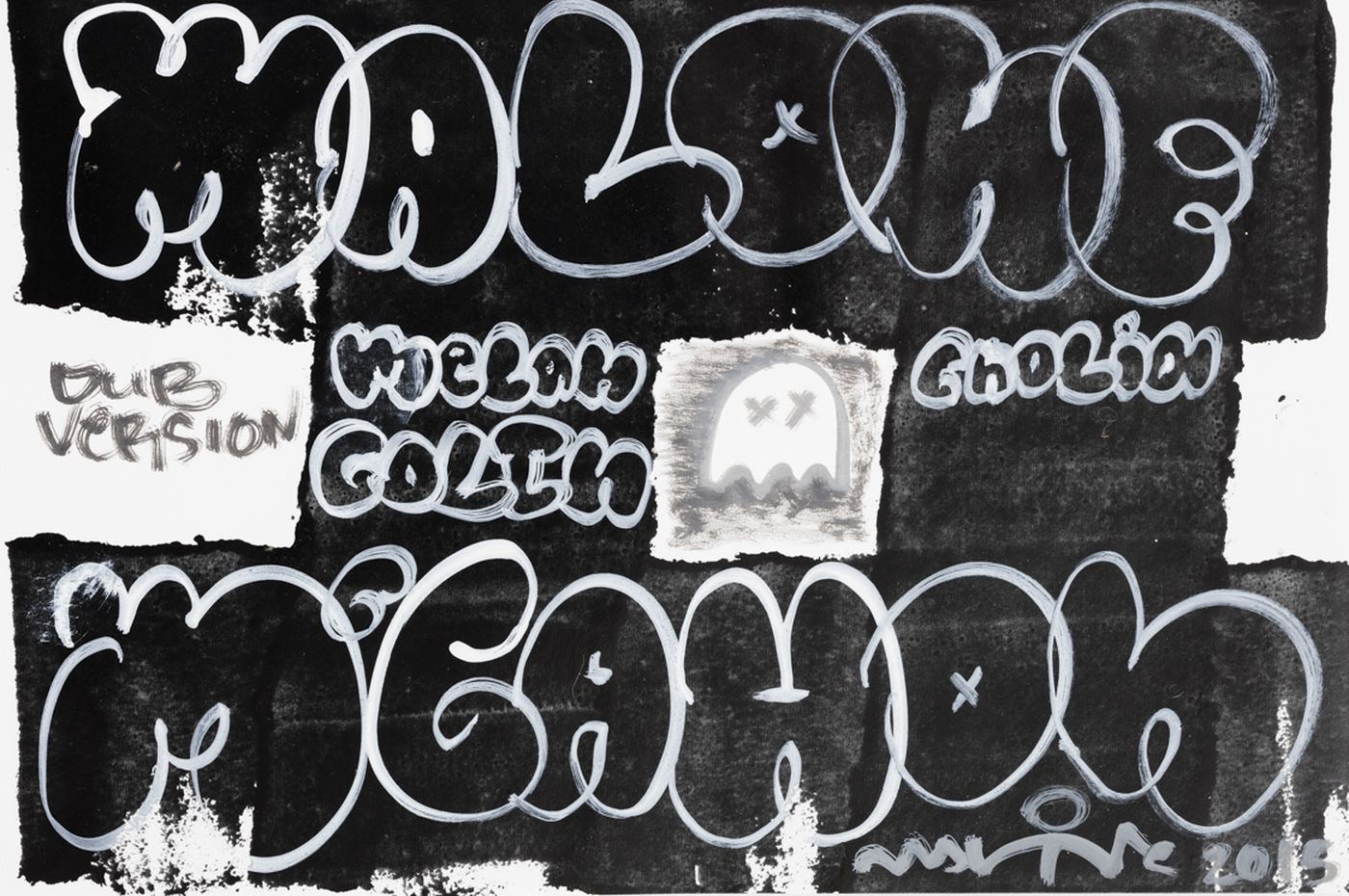

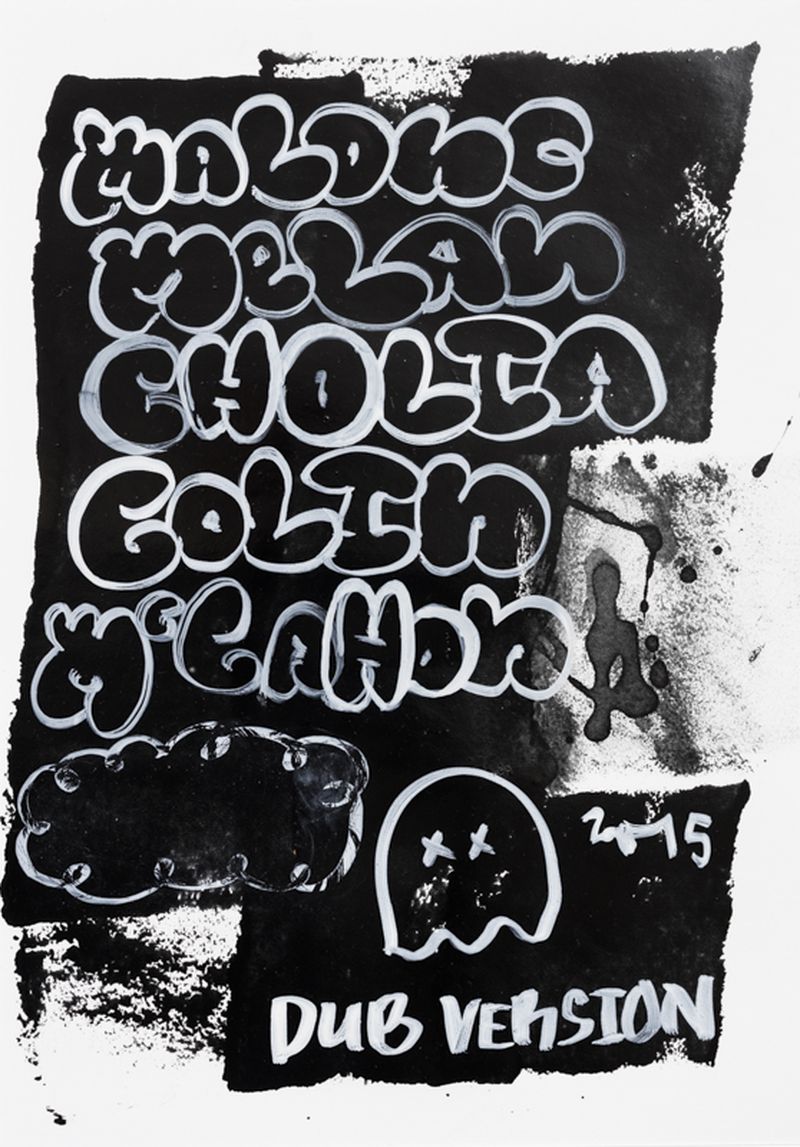

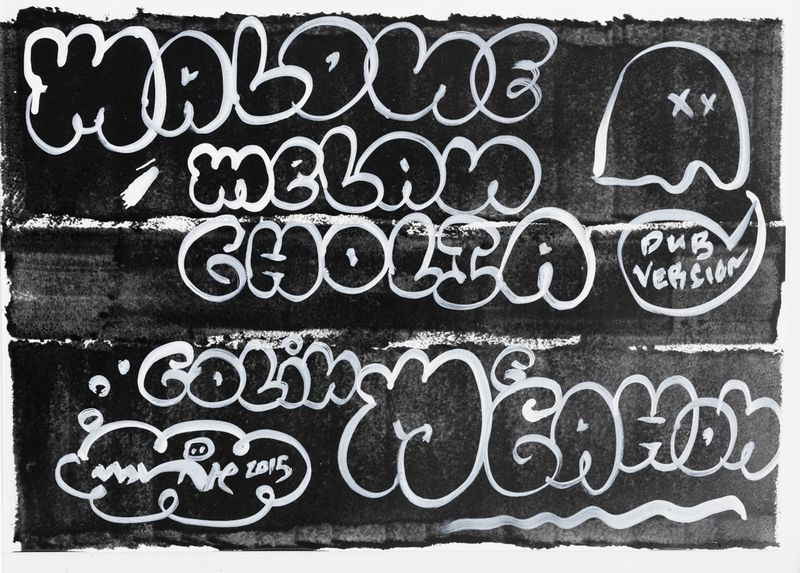

Untitled 1 (Malone, Melancholia, Colin McCahon)

2015

gesso, solpah and ink on paper, series of 8

420 x 300mm

$750 (unframed)

Contact us to purchase this edition.

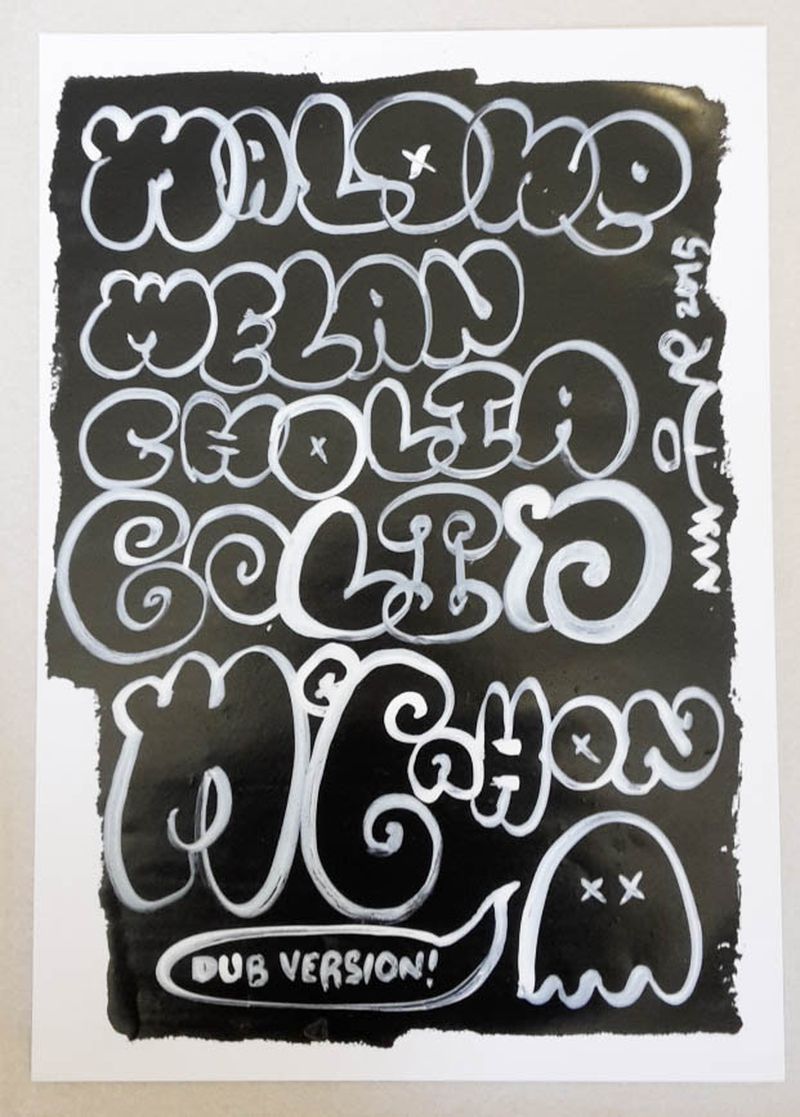

Daniel Malone

Untitled 3 (Malone, Melancholia, Colin McCahon)

2015

gesso, solpah and ink on paper, series of 8

420 x 300mm

$750 (unframed)

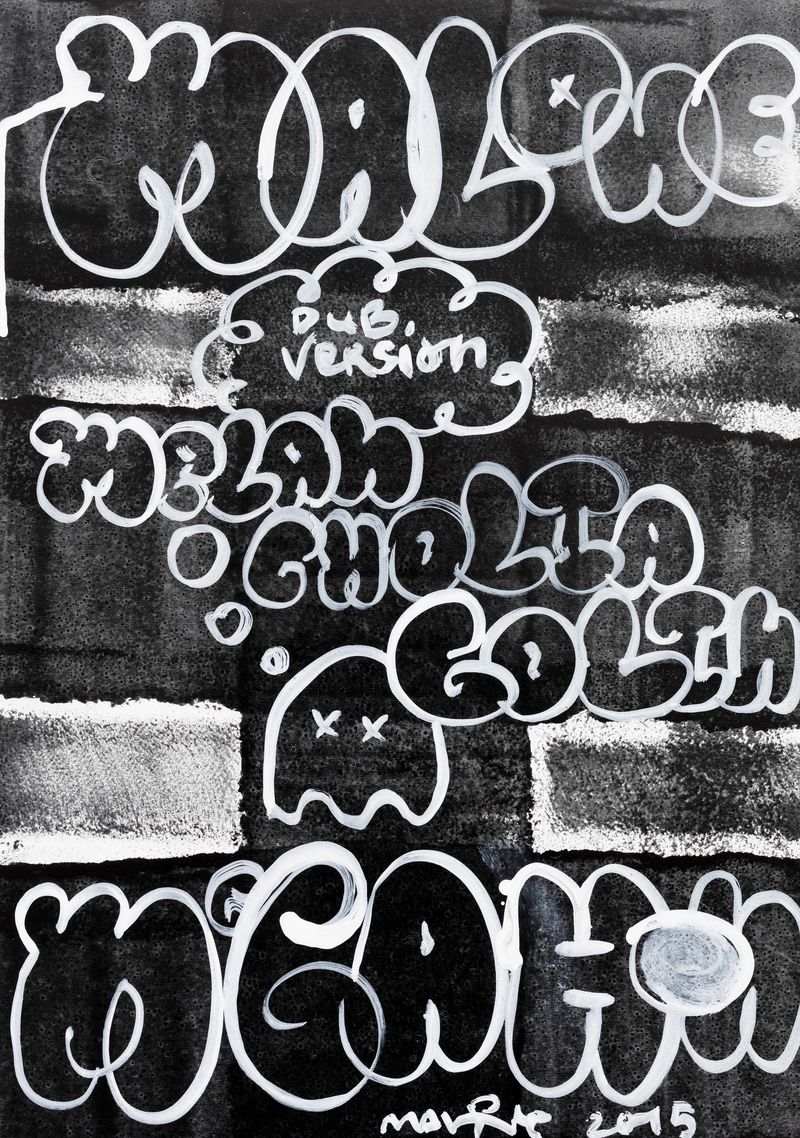

Daniel Malone

Untitled 4 (Malone, Melancholia, Colin McCahon)

2015

gesso, solpah and ink on paper, series of 8

300 x 420mm

$750 (unframed)

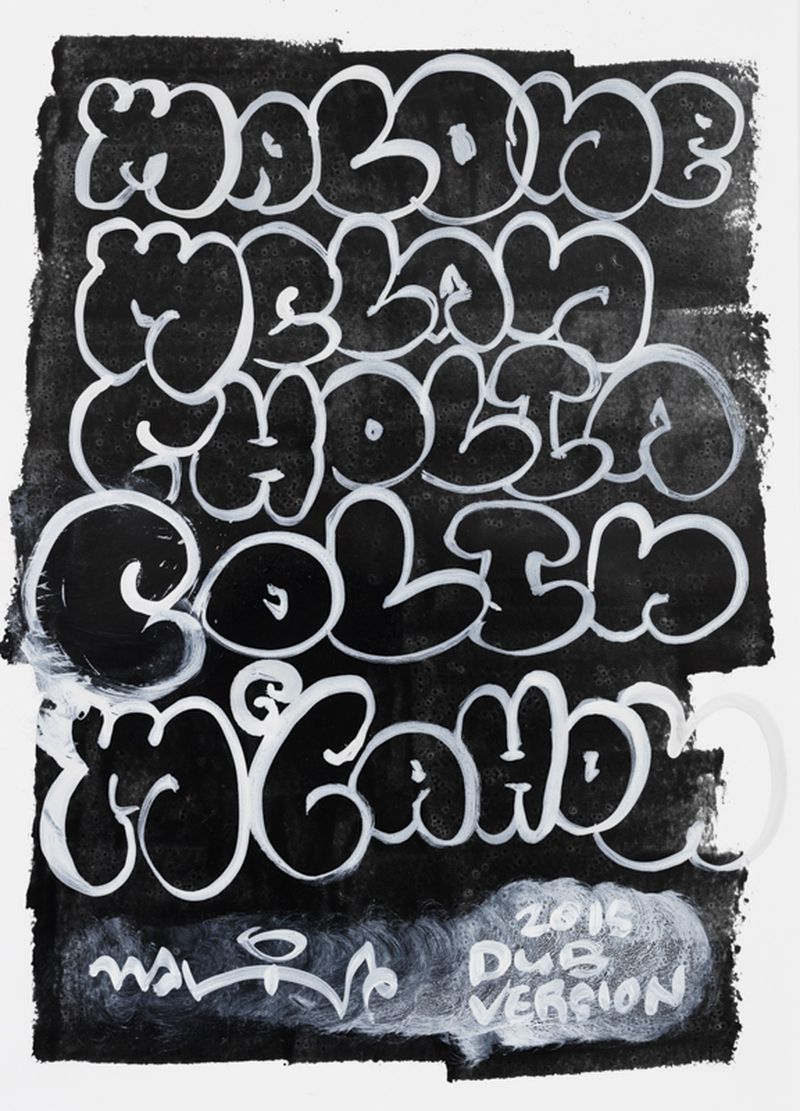

Daniel Malone

Untitled 5 (Malone, Melancholia, Colin McCahon)

2015

gesso, solpah and ink on paper, series of 8

420 x 300mm

Collection of McCahon House Trust

Daniel Malone

Untitled 6 (Malone, Melancholia, Colin McCahon)

2015

gesso, solpah and ink on paper, series of 8

420 x 300mm

Sold

Daniel Malone

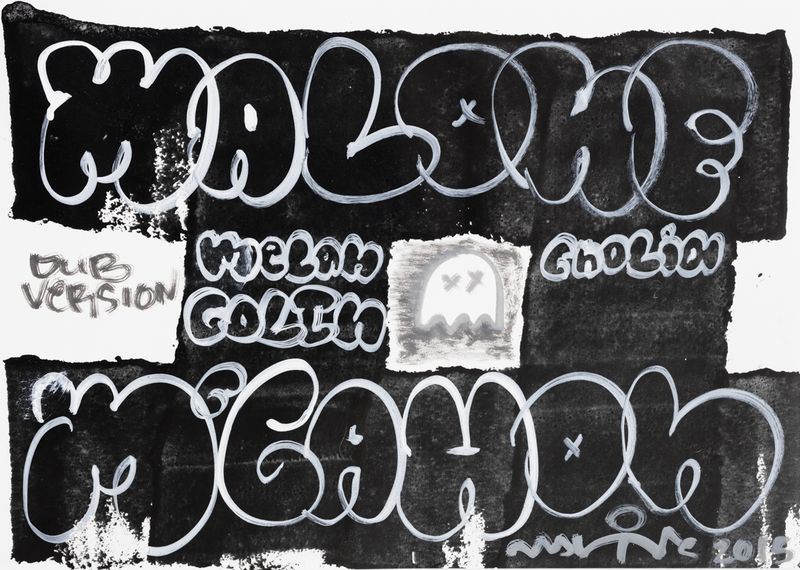

Untitled 2 (Malone, Melancholia, Colin McCahon)

2015

gesso, solpah and ink on paper, series of 8

300 x 420mm

$750 (unframed)