- Amy Howden-Chapman2014

- Ana Iti2020

- Andrew McLeod2007

- Andy Leleisi’uao2010

- Anoushka Akel2024

- Ava Seymour2009

- Ayesha Green2022

- Ben Cauchi2011

- Benjamin Work2024

- Bepen Bhana2016

- Campbell Patterson2015

- Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss2021

- Dan Arps2014

- Daniel Malone2014

- Emily Karaka2021

- Emma Fitts2018

- Eve Armstrong2009

- Fiona Pardington2013

- Gavin Hipkins2007

- George Watson2024

- Glen Hayward2011

- Imogen Taylor2017

- James Robinson2007

- Jess Johnson2019

- Jim Speers2010

- Juanita McLauchlan2025

- Judy Millar2006

- Kathy Barry2012

- Lisa Reihana2009

- Liyen Chong2012

- Louise Menzies2016

- Luise Fong2008

- Madison Kelly2024

- Martin Basher2010

- Matthew Galloway2025

- Michael Stevenson2023

- Moniek Schrijer2021

- NELL2023

- Neke Moa2023

- Nicola Farquhar2018

- Oliver Perkins2017

- Owen Connors2023

- Regan Gentry2012

- Richard Frater2020

- Richard Lewer2008

- Rohan Wealleans2008

- Rowan Panther2025

- Ruth Buchanan2013

- Sarah Hudson2025

- Sarah Smuts-Kennedy2016

- Sefton Rani2025

- Sorawit Songsataya2018

- Steve Carr2020

- Suji Park2015

- Tanu Gago2022

- Taro Shinoda2017

- Tiffany Singh2013

- Tim Wagg2019

- Wayne Youle2019

- Zac Langdon-Pole2022

- Zena Elliott2026

Oliver Perkins

YEAR OF RESIDENCY

May - July 2017

If the works in Japanese Laurel involve a reordering of elements, they also involve a reconfiguration of painting and sculpture. In past years, Perkins worked more explicitly within the tradition of painting, depending on its well-established vocabulary even as he challenged its forms. Aspects of the vocabulary persist. Dowelling tends to function as a framing device, but it is never all-enclosing. Similarly, canvas is an essential material, but it is deployed like the fabric it is: overlaid, rather than stretched in the traditional manner, allowed to pucker and, in places, to fray.

Oliver Perkins, Untitled, 2018, acrylic, dowel, rope and staples, 1600 x1000mm

Oliver Perkins, Dry Dock, 2018 acrylic, ink, plywood, dowel, canvas, screws and staples, 620 x 430mm

Between old new beginnings and aggregate categories, there’s an enticing idea of breaking things down and putting them together. A scrolled-back, shifty, recombinatory, and flexible form that feels right.1

—Matt Saunders

A painting that exceeds itself begs a profound question: How can one delimit any thing—even that most ostensibly autonomous thing, a painting?2

—David Joselit

I first meet Oliver Perkins several weeks into his residency at Parehuia, a purpose-built studio and house that lies behind the humble former home of Aotearoa’s best-known Pākehā artist, Colin McCahon. I am here to learn about Perkins’ latest works, soon to be show at the nearby Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery. While orderly, the studio space provides evidence of enthusiastic experimentation. Scraps of canvas bear monoprints of the poetical names of Resene paints, one of which, Japanese Laurel, will become the title of Perkins’ exhibition. Like his fellow Cantabrian, McCahon, before him, Perkins is playing with text.

Work benches are stacked with pots of paint, lengths of thick dowelling, and shallow box-forms made of plywood. Hanging on an adjacent wall, illuminated by a feeble winter sun filtering through the damp surrounding bush, are paintings assembled from these elements. Each comprises a plywood form and three pieces of dowelling: two crowning the form (abutting one another like the rollers of a laundry wringer or an ink grinding mill), the third kissing its bottom edge. Each work is coated with three tones of house paint: one for the face, one for the crown and sides, one for the lower length of dowelling.

As with all Perkins’ works, the paintings possess an immediate, intuitive rightness. The physical elements and colours are in easy balance. Their formal restraint, not to say simplicity, inevitably draws you in close, summoning you to attend to every visible surface and edge, every quirk of the materials and their combination. Unlike previous works by Perkins, which relied heavily on the ingredients associated with painting qua fine art, these depend on more commonplace, utilitarian substances. Consequently, they also direct attention outward to the world of everyday painted objects and spaces in which they exist.

Looking at the face of one work, I see McCahon House, which— like so many homes in the Waitākere Ranges—is painted a similar rust red. This is not to say that the work is necessarily meant to refer to the building, much less represent it. Perkins is drawing on what’s at hand, including the big box hardware centre ‘down the road’ in New Lynn, and the timber and paint products available therein. And this process is as much about finding parameters, an order for his practice, as it is about nodding towards the local built environment, the home handy-worker, McCahon making do with a pot of enamel house paint and an offcut of linen.

Still, there can be no doubt that architecture marks Perkins’ practice. The artist notes that the works at Parehuia are modelled loosely on the architrave, the element that sits immediately atop column capitals in classical architecture. Perkins’ 2017 exhibition Translations, at Hopkinson Mossman in Tāmaki Makaurau, was accompanied by a book of photographs taken by the artist of apartment buildings in the Spanish city of Alicante, for some time his place of residence. The show title ostensibly referred less to movement between countries and spoken languages than to a process of recasting architectural elements and modes as artistic ones.

Comparing book and show, it was possible to draw connections. The dowelling in one work could be understood to echo tubular balcony railings, the overall form of another a set of sliding doors. A third work suggested the basic template of a western building: a floor, walls, a pitched roof. More prominent, though, was the sense that Perkins was using the architectural system of reordering well defined elements as a model for his own method of constructing paintings. Certainly, his works—like the Greco-Roman temple or the Grey Lynn villa—may be reduced to a series of key components, able to be recombined in a great many variations.

In Japanese Laurel, the components are dowelling, plywood, canvas, paint, and—on one occasion—string. These form the lexicon of the show’s language and are attended by a generative grammar, a set of rules for the production of well-formed constructions. Dowelling, for instance, is deployed along edges, which are horizontal and vertical alone. Canvas is painted loose and only later wrapped round supports, which comprise plywood and sometimes abutting dowelling. It upholsters existing forms. Perkins, it transpires, has looked not only to the house, but also to the furniture—playing up the family resemblance between artworks and such cousin entities.

Isabelle Graw has commented that paintings, of all artworks, are especially apt to transcend their logical objecthood. This is because paintings—unlike, say, photographs—typically depend on marks and on shaped materials, both of which strongly point to the presence of an intelligent maker, the artist. Graw notes that ‘painting is able to produce the sensation that it has captured living labor’.3 Individual paintings thus project a certain vitality, which can begin to feel proper to them, creating a sense of their autonomy. This is perhaps most acute with works that are more sensational, less legible, as are Perkins’

The paintings in Japanese Laurel, however, enjoy an additional, less typical sense of vital autonomy. The grammar of elements yields a heightened sense of self-organisation. Considered en masse, one can almost imagine the works reconfiguring themselves: pieces of dowelling rolling up and down or back and forth, panels of plywood floating in and out to fill or vacate spaces, swathes of canvas wrapping themselves round forms. Just as an all-over painting by Jackson Pollock implies the potential extension of its marks beyond the limits of the canvas, so a cluster of works by Perkins implies a potential multiplicity of kindred forms beyond those witnessed.

The serial nature of the works does not—to borrow a phrase from David Joselit—‘eclipse the individual’.4 The restricted toolkit tends to encourage one to attend to the minutiae. Small differences become large, large differences huge. Within each work, a tension grows between consideration of the constituent elements and the overarching form. I begin to obsess over details visible only from the most awkward of angles. I have to remind myself to step back, to consider the whole of the work. And then there’s the ensemble, and then all the diverse works Perkins has made over the years—each whole being quite other than its parts.

A message arrives from Perkins. It includes a link to an essay called ‘Theory of the Non-Object’. Written by the late Ferreira Gullar, a theorist of the Brazilian neo-concrete movement of geometric abstraction, it advocates for painting that exceeds the bounds of convention. It is peppered with polemic. Gullar decries tachisme and l’art informel, complaining of its proponents, ‘Rather than rupturing the frame so that the work can pour out into the world, they keep the frame, the picture, the conventional space, and put the world (its raw material) within it.’5

He is not, per se, for a reaction against traditional forms of painting. He is critical of both Lucio Fontana’s sliced canvases, which he sees as a childishly literal attack on an already obviously fictive space, and Alberto Burri’s strident use of unconventional materials, which he sees as little more than an aestheticized replay of Dada techniques. At heart, his grouse seems to be with the reassertion of the primacy of the painting tradition implied by simple rebellion (Fontana) and the impotent mixing in of new ingredients (Burri). But what’s the solution?

Gullar calls for work that is untraditional rather than anti-traditional. The artist must strive not only to exceed the conventional frame (both literal and figurative), but also to bridge the old boundaries between art forms. Such a bridging, he suggests, takes place in the paintings of Lygia Clark and the sculptures of Amílcar de Castro, which share more in common with one another than do any number of works historically lumped together as sculpture. Painting and sculpture, he argues, are converging, giving rise to a class of entity he refers to as the ‘non-object’, an artwork ‘freed from any signification outside the event of its own apparition’.6

If the works in Japanese Laurel involve a reordering of elements, they also involve a reconfiguration of painting and sculpture. In past years, Perkins worked more explicitly within the tradition of painting, depending on its well-established vocabulary even as he challenged its forms. Aspects of the vocabulary persist. Dowelling tends to function as a framing device, but it is never all-enclosing. Similarly, canvas is an essential material, but it is deployed like the fabric it is: overlaid, rather than stretched in the traditional manner, allowed to pucker and, in places, to fray.

The artist tells me that his intention is to ‘keep the construction commensurate with the painting’, not to allow the elements of paint to dominate the built form, the architecture of the work. I’ve no qualms about calling Perkins’ works paintings, both because they retain sufficient traces of the tradition (to say nothing of paint the substance), and because, after modernity, the category painting can accommodate more than a little protrusion. But in essence they are uncategorical. They are sculptural. They are painterly. They are non-objects, in Gullar’s formulation, lending the spaces they inhabit precisely what he calls for: significance and transcendence.7

I find myself engaging with the works in Japanese Laurel on a sensational level first and foremost. I approach the show by way of the main stairwell in Te Uru. The steps are fortified against tread-wear with a butter-coloured linoleum. As I reach the landing, a large oblong work comes into view. It is saturated in a sympathetic yellow. The harmonising of floor treatment and painting should be too obvious, but it isn’t, perhaps because Perkins’ works have an uncanny ability to insinuate themselves into spaces—to feel inherent rather than dropped in from the outside.

I’ve anticipated the crowd and have the gallery mostly to myself. My eyes roam round walls and works, tumbling into voids of colour scumbled over fabric, snapping back as they meet passages of glossy painted wood. Exhibitions inevitably key one’s experience of a space and moment to some extent, but this room feels unusually under the influence of Perkins. I think suddenly of Wallace Stevens and particularly ‘The Idea of Order at Key West’: ‘the maker’s rage to order’, where rage implies will and passion, and the maker becomes a momentary Creator, takes charge of your guts.8

There’s a lot of order here, but it isn’t unfettered. If a key project of Perkins’ is to balance structure and surface, he is also attentive to offsetting rules with play, method with intuition. Built tension is consistently punctured and punctuated: sometimes by a tiny drip of paint, a vestigial nail hole, or a fragment of masking tape; more often by the casual application of colour to canvas. In places, the strokes (ostensibly rolled rather than brushed) seem quite incidental. The canvas takes on the appearance of a test swatch or even a drop cloth. The finished work is not merely informed by studio experimentation; it wears it on its sleeve.

Embracing improvisation and depending on reconfiguration, Perkins’ works crackle with freshness. This is not to say that they are preoccupied with being ‘new’, nor that they pretend to shake off the art histories out of which they inevitably grow. On the contrary, they resonate strongly with the work of earlier artists. Spliced lengths of dowelling recall Donald Judd’s Progression works. Fields of pigment put me in mind of Yves Klein, misty edges Mark Rothko. Viewed from the side, dowelling and plywood form a bar and lobe after the fashion of pītau regulated by Gordon Walters. Julian Dashper’s deconstructive chuckle is in the air.

McCahon is present, too—subtly. He’s not only in the house paint and rough-cut canvas, but also in the letters that emerge vaguely in several works: Ls, Is, or an E on its back in one piece, tau forms in others. Is this Perkins’ covert attempt at homage? Have these elements emerged quite unbidden? Or have I imposed them, not reading a latent story, but writing my own over the top? I decide that it doesn’t matter. I overhear a couple rhapsodising over the way one work suggests the Waitākere bush. And why not? With Perkins’ work, one registers an immanent sense of order, then is free to be fanciful.

At Parehuia, there is a post-opening gathering. It’s cold and damp, but not so cold and damp that you feel it in your marrow. The studio has been cleared but hanging on the walls are a few architrave works that didn’t make it into the ‘final cut’ of Japanese Laurel. The architectural nature of the panels is quite unmissable. They trace the perimeter of the room, embrace the gathered crowd. Two are painted in the same palette, differing only in scale. They might be the same work at different stages of growth. They might once have been a single work, now chopped in two. They might even, I think fancifully, be sections of an infinitely extending band.

I home in on one of the works, the better to establish its haecceity, the ‘thisness’ that separates it from its siblings and all other things. The wall behind bears traces of paint. I’m immediately reminded of a piece of haphazardly splotched linen in a Perkins from 2012. The borders of the architrave wobble. In a world and moment replete with site-responsive, performance, and participatory art, it would not be surprising if Perkins’ overtly object-based practice were more fixed, more contained. But, time and again, it overflows, leaks into the wider world—not unlike the voices of a party of revellers, echoing out into a mild midwinter night.

Essay commissioned by McCahon House Trust on the occasion of Oliver Perkins’ residency and resulting exhibition, Japanese Laurel, 5 August - 8 October 2017, Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery

- Matt Saunders, ‘Thread, Pixel, Grain’, in Painting Beyond Itself: The Medium in the Post-Medium Condition, ed. Isabelle Graw and Ewa Lajer-Burcharth (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2016), 173–174.

- David Joselit, ‘Marking, Scoring, Storing, and Speculating (on Time)’, in Painting Beyond Itself: The Medium in the Post-Medium Condition, ed. Isabelle Graw and Ewa Lajer-Burcharth (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2016), 19.

- Isabelle Graw, ‘The Value of Liveliness: Painting as an Index of Agency in the New Economy’, in Painting Beyond Itself: The Medium in the Post-Medium Condition, ed. Isabelle Graw and Ewa Lajer-Burcharth (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2016), 82.

- David Joselit, ‘Marking, Scoring, Storing, and Speculating (on Time)’, 18.

- Ferreira Gullar, ‘Theory of the Non-Object’, trans. Michael Asbury, in Cosmopolitan Modernisms, ed. Kobena Mercer (London: Institute of International Visual Arts, 2005), 173. See http://ualresearchonline. arts.ac.uk/5392/.

- Gullar, ‘Theory of the NonObject’, 173.

- Gullar, ‘Theory of the NonObject’, 171.

- 8 Wallace Stevens, ‘The Idea of Order at Key West’. See https:// www.poetryfoundation.org/ poems/43431/the-idea-of-orderat-key-west.

Artist Artworks

Oliver Perkins

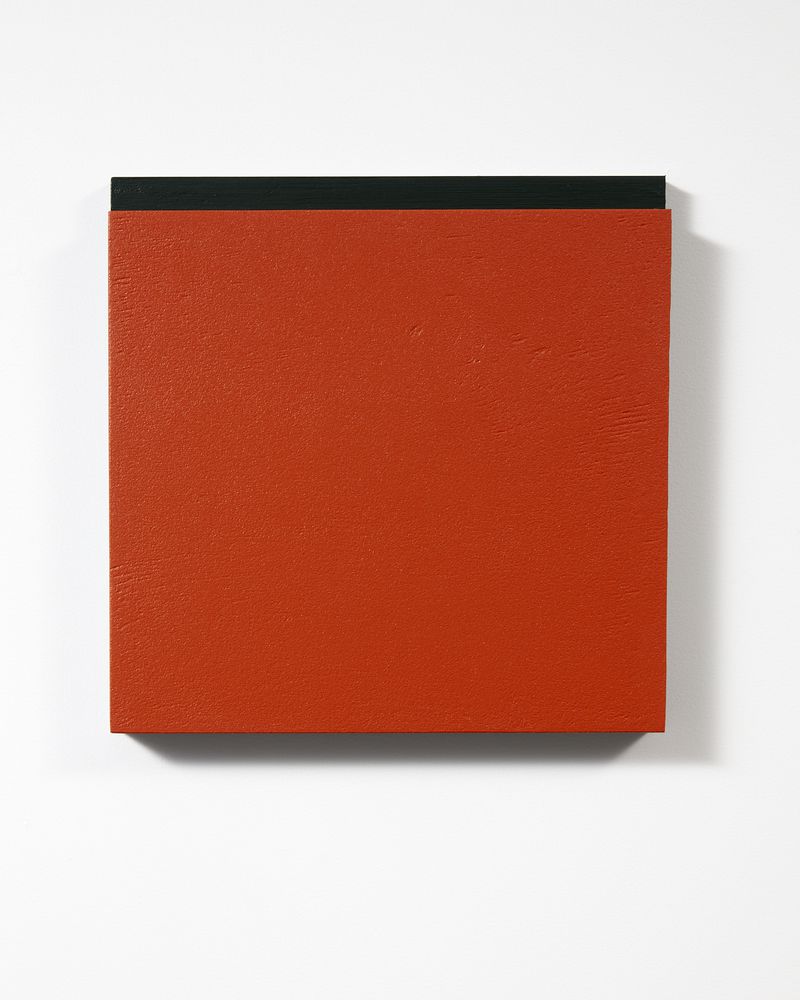

Untitled (Midnight Moss)

2018

acrylic and primer on plywood

305 x 305mm

Photo: Sam Hartnett

Collection of McCahon House Trust

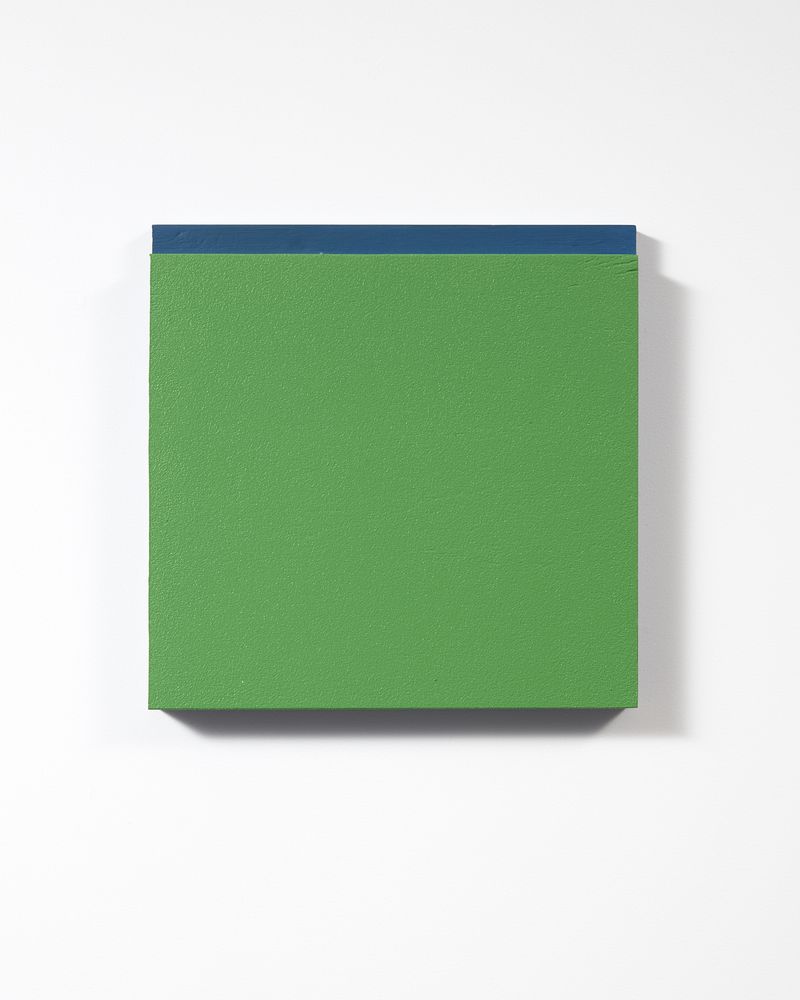

Oliver Perkins

Untitled

2018

acrylic and primer on plywood

305 x 305mm

Photo: Sam Hartnett

Sold

Oliver Perkins

Untitled

2018

acrylic and primer on plywood

305 x 305mm

Photo: Sam Hartnett

Sold

Oliver Perkins

Untitled

2018

acrylic and primer on plywood

305 x 305mm

Photo: Sam Hartnett

Sold