- Amy Howden-Chapman2014

- Ana Iti2020

- Andrew McLeod2007

- Andy Leleisi’uao2010

- Anoushka Akel2024

- Ava Seymour2009

- Ayesha Green2022

- Ben Cauchi2011

- Benjamin Work2024

- Bepen Bhana2016

- Campbell Patterson2015

- Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss2021

- Dan Arps2014

- Daniel Malone2014

- Emily Karaka2021

- Emma Fitts2018

- Eve Armstrong2009

- Fiona Pardington2013

- Gavin Hipkins2007

- George Watson2024

- Glen Hayward2011

- Imogen Taylor2017

- James Robinson2007

- Jess Johnson2019

- Jim Speers2010

- Juanita McLauchlan2025

- Judy Millar2006

- Kathy Barry2012

- Lisa Reihana2009

- Liyen Chong2012

- Louise Menzies2016

- Luise Fong2008

- Madison Kelly2024

- Martin Basher2010

- Matthew Galloway2025

- Michael Stevenson2023

- Moniek Schrijer2021

- NELL2023

- Neke Moa2023

- Nicola Farquhar2018

- Oliver Perkins2017

- Owen Connors2023

- Regan Gentry2012

- Richard Frater2020

- Richard Lewer2008

- Rohan Wealleans2008

- Rowan Panther2025

- Ruth Buchanan2013

- Sarah Hudson2025

- Sarah Smuts-Kennedy2016

- Sefton Rani2025

- Sorawit Songsataya2018

- Steve Carr2020

- Suji Park2015

- Tanu Gago2022

- Taro Shinoda2017

- Tiffany Singh2013

- Tim Wagg2019

- Wayne Youle2019

- Zac Langdon-Pole2022

- Zena Elliott2026

Sorawit Songsataya

YEAR OF RESIDENCY

January - March 2018

Sorawit Songsataya is primarily interested in craft, textiles, hand-made objects and their connection to computer technology. Their practice forms at the intersection of digitised labour and traditional craftsmanship. Employing both analogue and digital film and animation, sculpture, new media, synthetic, and organic materials, Songsataya explores the intricacy of what it means to ‘make’ today: how political and historical dimensions are embedded and layered in the process of making, in material selection, modes of research, and methods of presentation. Often resolved in a form of video installation, Songsataya’s handmade and machine-crafted sculptural objects manifest the tangibility of their moving-image work, in which the relationship between the visual and the bodily is intensified through the process of materialisation; of 3d animation into 3d-printed and machine-made forms. Songsataya’s works aim to understand and unravel the kinship between making, remaking and unmaking the image/object of the past, present, and future.

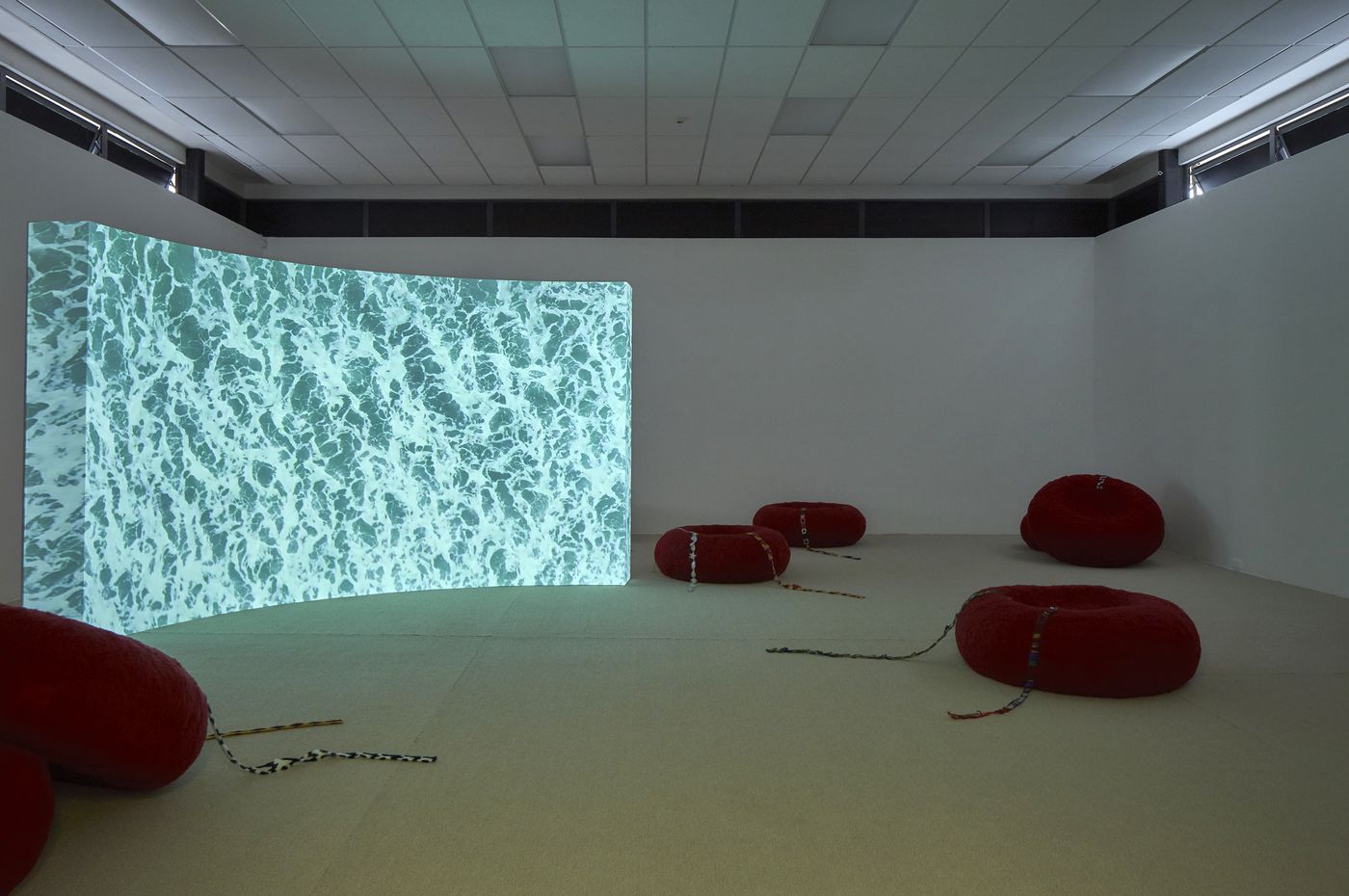

Sorawit Songsataya, Jupiter (installation view), 2019. Six-channels digital video, merino wool, copper wire, cotton twine, pressed flowers. Dimensions variable. Photograph by Sam Hartnett

Sorawit Songsataya, Offspring of Rain, 2019. Digital video with sound by Antonia Barnett-McIntosh. 10:00 min. Photograph by Cheska Brown

Sorawit Songsataya, Morning Dew, 2019. Heat-pressed and dried plant material, resin. Dimensions variable. Photograph by Cheska Brown

Sorawit Songsataya left Chiang Rai, a mountainous city in Northern Thailand, at age fifteen. They followed their father to Auckland, where they both gained residency. It was in either 2001, or 2002, Songsataya says. The artist’s mother still lives in Chiang Rai, running a bed and breakfast there.

Sorawit held the McCahon House residency from January to March 2018. During this time, the artist hand-felted enormous blood cells and DNA-like strips of imagery: love hearts, birds, sea shells. From Titirangi, they immediately left New Zealand for a three-month residency at the Tensta Konsthall in Stockholm, Sweden.

The lineage of Songsataya’s practice is marked by periods of investigation into different craft traditions, and their positions in history and culture. When one speaks of craft in the context of contemporary art, it is immediately complicated by the gendered, cultural, and imperial structures that have historically defined their interaction. The artist’s approach is one of devotion to craft as a cultural phenomenon, with an emphasis on rigorous research and curiosity for methods in their time and place.

Kites are often zoomorphic—lattices of material cra ted in the image of birds, insects, dragons, and other creatures. Wind, spurred by the geographical exchange of heat, is their animating force. Darting and zigzagging, the kite becomes a creature, a cultural animal. The human is positioned in-between, elaborating this continuity.

In Sweden, Sami artist and activist Katarina Pirak Sikku invited Songsataya to her home. Together they looked at a carving by her father, Lars Pirak. Later, they went up her mountain to an impoundment facility, where the river is stored to produce electricity in its controlled release through a turbine generator.

Afer ten months away, Songsataya returned to New Zealand in late January 2019 as Enjoy Public Art Gallery’s Summer Resident, living and working from Rita Angus’s Wellington cottage. During Songsataya’s residency, Angus’s fireplace became a soldering station, where the artist fused recycled copper wire to form the frames of kites. Jupiter, ดาวพฤหัส is their first show—back in Titirangi, again—since travelling.

Contemporary art, as a globalised cultural field, has afforded Songsataya’s travel. It has housed, moved, and remained constant to the artist. In this way, it has served as both material animating force and resting place for the articulation of experience and identity, a place in which traditional practices and forms can be transposed, meddled with, made different. Articulation on this personal scale is a process of coming to terms with identity via making: taking a zigzagging flight through the forces that have shaped oneself, traces of movement beholden to greater trajectories. Though contemporary art is an imperfect field, with its neutrality constantly in doubt, it is a place where these articulations can come to rest.

The kite, windmill, and wind turbine appear within a scaling dynamic; a genealogy of technological advance, a linear increase in size, prowess or reach. Together, they diagram a shift in register between local and planetary. While the kite design the artist deploys is embedded within localised networks of meaning, the context of contemporary art opens it up to planetary concerns.

At birth, the Loggerhead sea turtle is imprinted with the unique magnetic signature of its birthplace. It is drawn to this specific part of the coastline throughout its life: a magnetic home, where it will return from vast migrations to mate and lay eggs. In describing this process, we find ourselves in danger of either anthropomorphising the turtle, or ascribing its return to a blind biological impulse. We know this: Loggerhead turtles have a home, and regardless of whether they think of it, or long for it, they return there, over and over again.

At Riddu Riđđu, an annual Sami music and culture festival held in Olmmáivággi (Manndalen) in the Gáivuotna (Kåjford) municipality in Norway, Songsataya learned how to embroider and turn fish skin into leatherwear from Eastern Russian Nanai practitioners.

Songsataya transposes the traditional form of a Thai kite into the field of contemporary art. The artist has used the ratios of a traditional kite without adhering to strict dimensions. Rather than silk and bamboo, they’re made from felt and copper. Rather than joining this framework with string, each part is soldered together. Copper is chosen for its conductivity, a material able to transmit information or electrical impulses between two points.

The mundane way in which humans capture material flows and transform them into life-sustaining forces, while they might seem to dislocate us from our environment, are an expression of embeddedness. Networks of city lights and communication are sustained by the flow of river water, sustained by the ebb of the water cycle, sustained by global exchanges of heat.

Cinema 4D, the software Songsataya uses to create 3D animations, comes packaged with a complex physics simulator. The physical rules of exchange are simulated in microcosm, lending dynamic life to fur, fabric, grass, and hair. These are the fuzzy substances Songsataya often returns to, often presenting them in exaggerated states of physical flux, traces of exchange mapped out across their surface.

In the South Island of New Zealand, moist air flows in from the Tasman Sea and rises up the Southern Alps, cooling as it goes. Much of the moisture is left behind, feeding the rainforests of the West Coast. What is left on the other side is a cloud formation unique to Canterbury, the Nor’west arch, a high white cloud in a clear blue sky. The Nor’wester, a strong dry wind, is anecdotally associated with animating human moods: anger, anxiety, or mania. There is some evidence for a causal link between the wind and social disorder.

The windmill is earthbound. It sits in the flow, capturing and commodifying its wealth. The windmill doesn’t resemble a creature of any kind. It is optimised to function as a mirror image of the topology of air flow.

Our expressions of nature are continuous with it. Working backwards from the elaborate fiction of culture, into nature, we find ourselves using the language of commodification, capture, excess, production and labour. Working the other way, we find ourselves in metaphor.

The social role of kites in Thailand is entangled with the demarcations of competition and gender roles. The kite flying competition between Chulas and Pakpaos, two species of traditional kites, is underpinned by rigorous and complex rules that situate the two as male and female, caught in a game of capture and evasion. Their characteristics embody traditional gender roles.

The artist learnt how to make the Jula and Pra Ruang kites from an elderly woman, an “aunty”, in Sukhothai - the first Thai capital and the birthplace of traditional Thai kite designs. On the family’s farm this knowledge passed from her hands to the artist’s. In this exchange—a week of intimate inheritance—heritage no longer seemed distant or abstract but active and obtainable.

Certain spiders will climb very high and release silk threads into the air, forming a triangular parachute. They use the flow of air and static electricity to disperse themselves across the surface of the earth, like seeds. They can travel many hundreds of kilometres this way.

Essay commissioned by the McCahon House Trust on the occasion of Sorawit Songsataya's residency and resulting exhibition, Jupiter, 23 February – 26 May 2019, at Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery

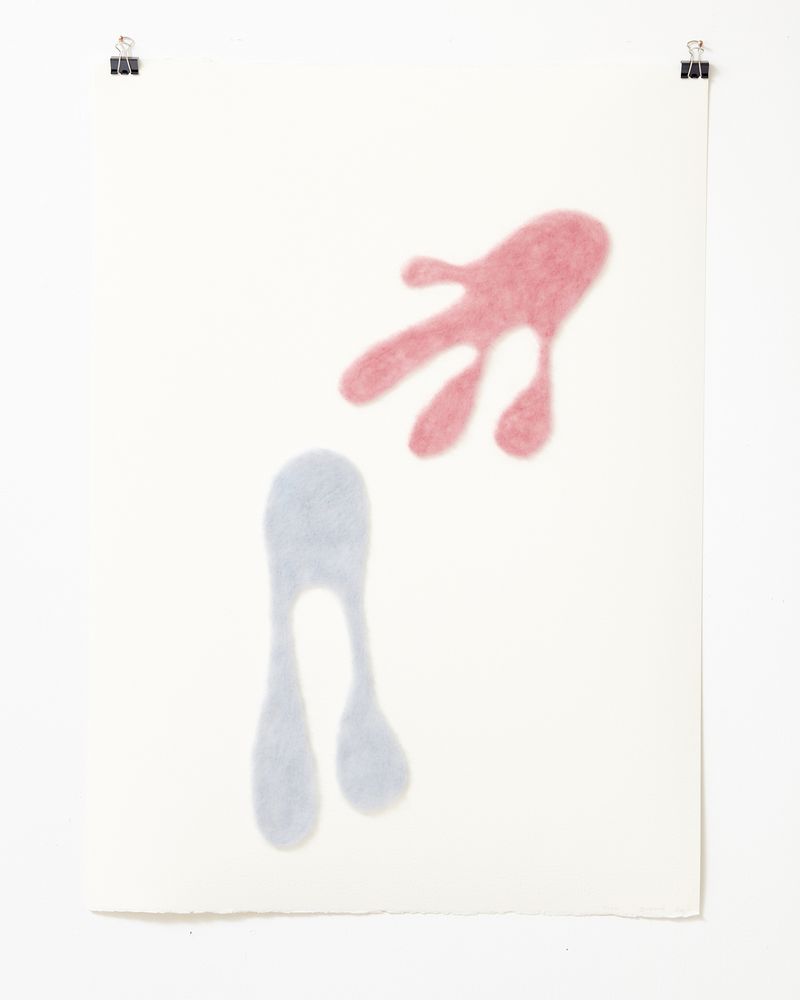

Artist Artworks

Sorawit Songsataya

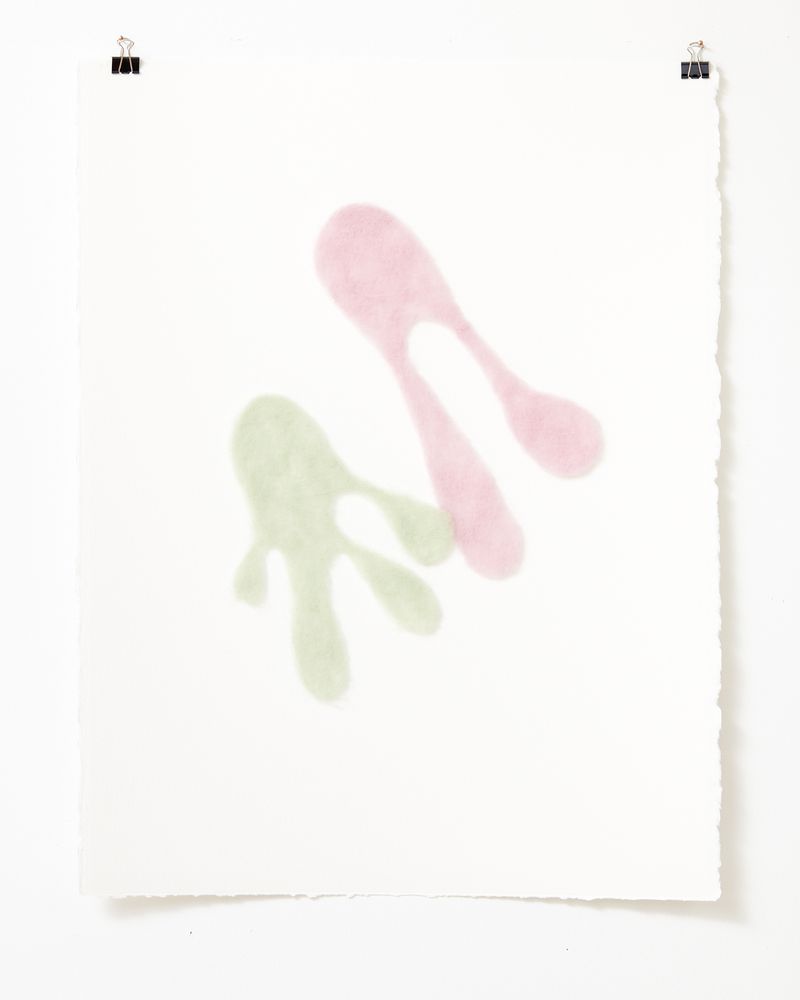

Gramsci's matisse II

2018

series of 5, hand-felt wool on Hahnemuhle Leonardo water colour paper 600gsm

760 x 560mm

$600 (unframed)

Photo: Sam Hartnett

Sorawit Songsataya

Gramsci's matisse I

2018

series of 5, hand-felt wool on Hahnemuhle Leonardo water colour paper 600gsm

760 x 560mm

Photo: Sam Hartnett

Sold out

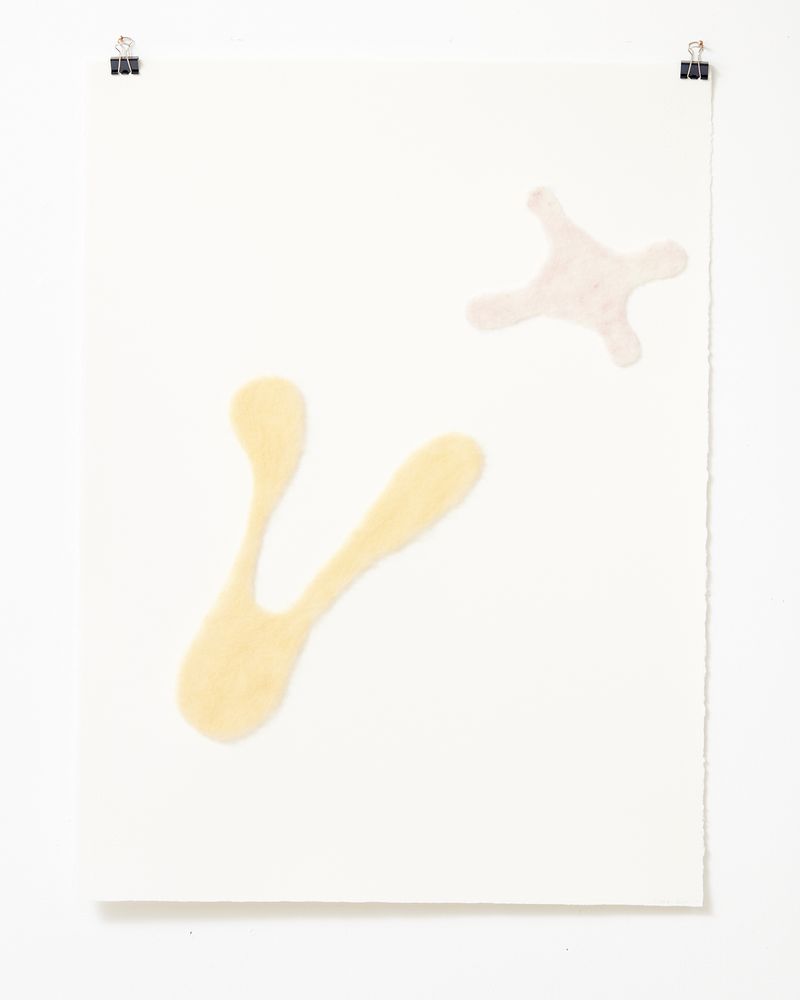

Sorawit Songsataya

Gramsci's matisse III

2018

series of 5, hand-felt wool on Hahnemuhle Leonardo water colour paper 600gsm

760 x 560mm

Photo: Sam Hartnett

Sold out

Sorawit Songsataya

Gramsci's matisse IV

2018

series of 5, hand-felt wool on Hahnemuhle Leonardo water colour paper 600gsm

760 x 560mm

Photo: Sam Hartnett

Sold out

Sorawit Songsataya

Gramsci's matisse V

2018

series of 5, hand-felt wool on Hahnemuhle Leonardo water colour paper 600gsm

760 x 560mm

Photo: Sam Hartnett

Collection of McCahon House Trust