- Amy Howden-Chapman2014

- Ana Iti2020

- Andrew McLeod2007

- Andy Leleisi’uao2010

- Anoushka Akel2024

- Ava Seymour2009

- Ayesha Green2022

- Ben Cauchi2011

- Benjamin Work2024

- Bepen Bhana2016

- Campbell Patterson2015

- Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss2021

- Dan Arps2014

- Daniel Malone2014

- Emily Karaka2021

- Emma Fitts2018

- Eve Armstrong2009

- Fiona Pardington2013

- Gavin Hipkins2007

- George Watson2024

- Glen Hayward2011

- Imogen Taylor2017

- James Robinson2007

- Jess Johnson2019

- Jim Speers2010

- Juanita McLauchlan2025

- Judy Millar2006

- Kathy Barry2012

- Lisa Reihana2009

- Liyen Chong2012

- Louise Menzies2016

- Luise Fong2008

- Madison Kelly2024

- Martin Basher2010

- Matthew Galloway2025

- Michael Stevenson2023

- Moniek Schrijer2021

- NELL2023

- Neke Moa2023

- Nicola Farquhar2018

- Oliver Perkins2017

- Owen Connors2023

- Regan Gentry2012

- Richard Frater2020

- Richard Lewer2008

- Rohan Wealleans2008

- Rowan Panther2025

- Ruth Buchanan2013

- Sarah Hudson2025

- Sarah Smuts-Kennedy2016

- Sefton Rani2025

- Sorawit Songsataya2018

- Steve Carr2020

- Suji Park2015

- Tanu Gago2022

- Taro Shinoda2017

- Tiffany Singh2013

- Tim Wagg2019

- Wayne Youle2019

- Zac Langdon-Pole2022

- Zena Elliott2026

Ana Iti

YEAR OF RESIDENCY

July - September 2020

Gate VII Ana Iti x Martin Bosley and Kono - September 2020

Ana Iti (Te Rarawa) is an artist based in Te-Whanganui-a-Tara. Often employing sculpture, video and text, her recent work explores the practice of history making through shared and personal narratives. Iti recently completed a MFA at Toi Rauwharangi Massey University Wellington. Recent exhibitions include The earth looks upon us /Ko Papatūānuku te matua o te tangata, Adam Art Gallery, Wellington (2018), Time is now measured in damage, Window Gallery, online (2018), (Un)conditional I,The Physics Room, Christchurch (2018).

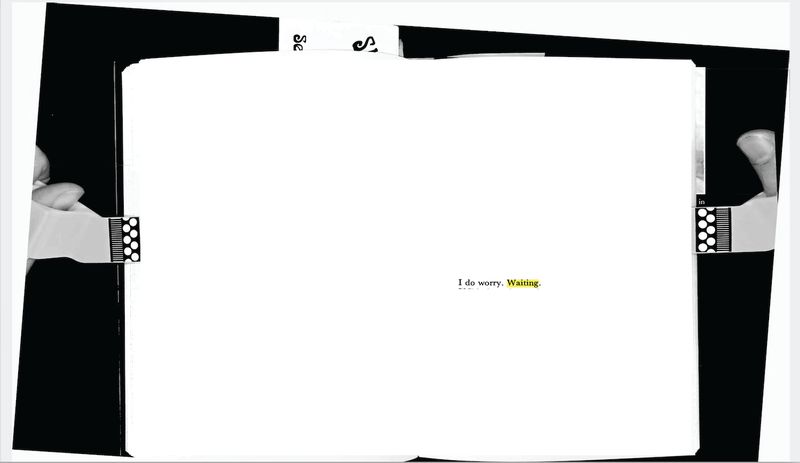

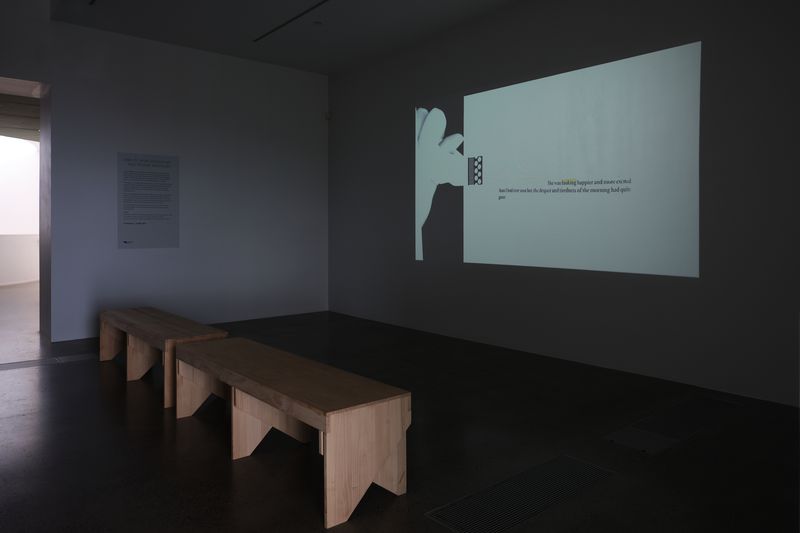

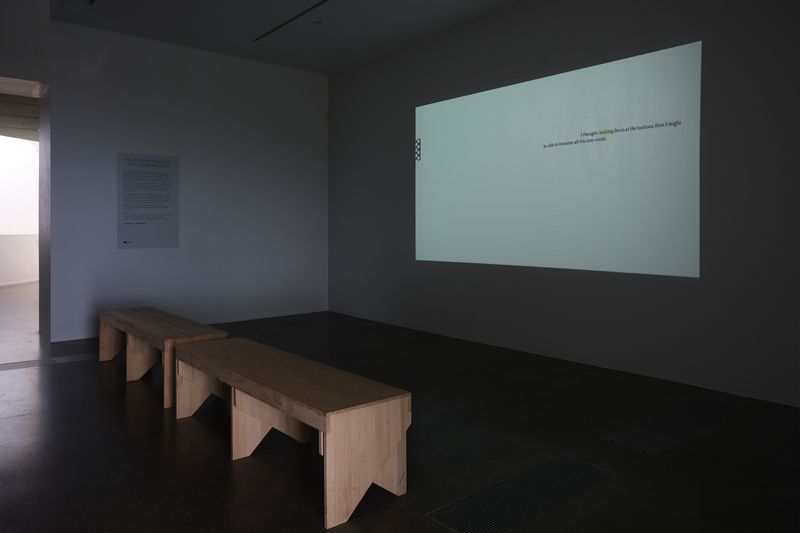

Still from Ana Iti's A dusty handrail on the track, 2021

I thought, looking down at the harbour, that I might be able to translate all this into words. June Mitchell, Amokura, 1978

I’ve spent quite a lot of time looking at your hands turning pages recently Ana, moving slow enough for a reader to follow. Your thumbs hold the tabbed pages to each side of the book, and isolated phrases appear, lit-up boats on the harbour. The page is dark like pre-dawn, contracted and dense in the anticipation of light.

I’ve spent quite a lot of time waiting for the narrative to emerge, gravity bearing down heavy on my shoulders as I sit here at my desk after the work day and read each sentence as it appears on the screen: “The forest trees themselves are waiting intently.” I’m glad to sit here, to be a reader as much as a viewer, to rest in the space between phrases. Nothing makes me sit as still as watching your videos, that’s what I’m thinking right now.

I’ve spent quite a lot of time wondering what it’s like to be there, with just the book and the camera, making this work, before it becomes solid and finished so you can leave it, have lunch, wash your hands, go back to the other things you’re doing. I can hear myself breathing as I watch it.

“I do worry, waiting” reads the line of text on the screen. Me too. I worry about these things: I worry about there not being enough time for the things I think I need to do; I worry about writing things that make no sense but nobody tells me; I worry about my teeth and my dry hands and I worry about saying the wrong thing. One reason I like to read is that it’s hard to worry, when you are reading.

The work is built in layers. A thick original layer of fiction texts by wāhine Māori is the foundation: Amokura (1978) by June Mitchell (Ngāti Raukawa, Te Arawa), a book on Meretini Te Akau1; Keri Hulme’s Te Kaihau: The Windeater (1986); and JC Sturm’s House of the Talking Cat (1983) A layer of darkness, which covers most of the original text. Not like redaction, or erasure, more like darkness itself, within which certain forms appear more clearly, are easier to hear. It says, “The sound track is full of night sounds from the bush.” There is no sound track to this work, but there is a layer of space in which I can hear the bush in the night time like I used to hear it in Ruapuke, morepork, and the achy sound of boney ti trees adjusting position against each other on the hill behind our house. There is the layer of the screen, my fingerprints on it visible against the black field of the image. There is the layer of the work’s title, A dusty handrail on the track, to lean on. And the exhibition title, How should we talk to each other? which is a question I have too. Learning language helps, and reading, because that can be a kind of dialogue, even if you’re reading the book 23 years after it was published, as I am. And also laughing, reading, “You walked up the path from this Ōtaki River, you the brisk Pākehā”, and recognise that talking to each other is not always earnest or about things that matter, that talking itself also matters.

In 2019, I watched another work of yours at The Dowse Art Museum in Te Whanganui-a-tara Wellington, Like everywhere, words come one foot after another, where a torch picks out a walking path from the darkness ahead. I can see the connection to this work, can feel how they make sense of each other in a way, are both searching for a language adequate to the experience of looking for something with your whole self. Watching Like everywhere made you feel the knowledge that exists in the soles of your feet, the way they might be able to understand and navigate a path in the darkness that your brain alone could not. The torch is useful, but it’s not offering enlightenment in itself, just enough information to allow you to keep walking in the dark.

This search for words is continued in How should we talk to each other? with a series of highlighted verbs appearing in the first part of the work: “looking”, ‘trying”, “waiting”, “research”: wanting, needing, putting your energy into trying to recover a story. The work of research is there too, “track” and “path” occur and recur, and I can feel you feeling your way through a methodical ordering of this wayward text. What is it like to want to understand, with your whole body? Is it like wanting to climb inside the book, and to find something substantial there, somewhere to sit? “Body to body” the words appear, “hand to hand”. The body of the text and the body of the reader sit together; there is the first phase of the work, where i’m leaning in to read each phrase or word as it arrives on the screen, and then there’s a phase where the page becomes somewhere for my mind to rest in the dark. Later in the work the page is white again, becomes a plain, a sail, a bedsheet, a wing, even. Becomes a room with the lights off and I'm lying here on my shoulder. These are the years of staying home now. No one sees as many exhibitions in the flesh. We read books, or we read books on the screen, and I ask you to send me images of the installation so I can see if my imagined version of how this work occupied the room is accurate, and how much that matters. I look at these in Ōtautahi, and rewatch the video, and the skies are different here now from when I saw it first in autumn. The dark is different here from the wet-dark of Tāmaki, from Titirangi where you made the work. Here where the trees are all gone and the swamps too, there are the thirsty hills that stand in your peripheral vision all the time even in the dark.

This work is all words, I could write about it for a long time, but finally, there is something that can not be translated. I wait for days for the experience of watching the work to crystallise into something else, that can be said. I hesitate. I look up ‘amokura’, a figurative term for a leader, and I see it is a red-tailed bird, too. I read, We watched the birds at every angle of flight, every rate of speed; not rarely they passed below us so swiftly that their plumes behind seemed but a diaphanous flash of strange brightness; sometimes more slowly in the sunlit air the hyaline red followed a ruddy haze, as a meteor’s radiance is shed astern. When floating with motionless wings, web, as well as shaft, were perfectly plain to the eye.”2

I’m looking up from the page again; looking up from the screen; looking up. I realise the work is not just the words but also the flick of turning pages, the moment between the last sentence and the one coming. It is the second after you read a line, and the words are no longer ‘perfectly plain to the eye’. It’s dark outside now, and the screen’s square of white light is reflected in the office windows. I sit still; not worried, not waiting. The words are the only thing that moves.

Essay commissioned by McCahon House on the occasion of Ana Iti's residency September - December 2020.

All images courtesy of Te Uru Waitakere Contemporary Gallery, 2020. Photograph: Sam Hartnett.

1. Meretini Te Akau was the granddaughter of Hape Tuarangi (ariki Ngāti Raukawa) and Te Akau o Tuhourangi (rangatira Arawa). June Mitchell’s ‘Amokura’ is included in Te Ao Mārama: Contemporary Māori Writing, compiled and edited by Witi Ihimaera, with contributing editors Haare Williams, Irihapeti Ramsden and D. S. Long (Auckland: Reed, 1992), 25.

2. W.H. Guthrie Smith, as cited on New Zealand Birds, Ngā Manu o Aotearoa (online): https://www.nzbirds.com/birds/amokura.html.