- Amy Howden-Chapman2014

- Ana Iti2020

- Andrew McLeod2007

- Andy Leleisi’uao2010

- Anoushka Akel2024

- Ava Seymour2009

- Ayesha Green2022

- Ben Cauchi2011

- Benjamin Work2024

- Bepen Bhana2016

- Campbell Patterson2015

- Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss2021

- Dan Arps2014

- Daniel Malone2014

- Emily Karaka2021

- Emma Fitts2018

- Eve Armstrong2009

- Fiona Pardington2013

- Gavin Hipkins2007

- George Watson2024

- Glen Hayward2011

- Imogen Taylor2017

- James Robinson2007

- Jess Johnson2019

- Jim Speers2010

- Juanita McLauchlan2025

- Judy Millar2006

- Kathy Barry2012

- Lisa Reihana2009

- Liyen Chong2012

- Louise Menzies2016

- Luise Fong2008

- Madison Kelly2024

- Martin Basher2010

- Matthew Galloway2025

- Michael Stevenson2023

- Moniek Schrijer2021

- NELL2023

- Neke Moa2023

- Nicola Farquhar2018

- Oliver Perkins2017

- Owen Connors2023

- Regan Gentry2012

- Richard Frater2020

- Richard Lewer2008

- Rohan Wealleans2008

- Rowan Panther2025

- Ruth Buchanan2013

- Sarah Hudson2025

- Sarah Smuts-Kennedy2016

- Sefton Rani2025

- Sorawit Songsataya2018

- Steve Carr2020

- Suji Park2015

- Tanu Gago2022

- Taro Shinoda2017

- Tiffany Singh2013

- Tim Wagg2019

- Wayne Youle2019

- Zac Langdon-Pole2022

- Zena Elliott2026

Sarah Smuts-Kennedy

YEAR OF RESIDENCY

September - November 2016

Smuts-Kennedy's practice is focused on a research-based investigation into fields of energy as they engage with conceptual thinking, both within art-based languages and other intuition driven modes of enquiry. Non-linear principles of biodynamic and Goethean agricultural theory—which she tests at her biodynamic, permaculture teaching garden 45 minutes north of Auckland—function as a central axis for her research.

Born in Lower Hutt in 1966 Smuts-Kennedy graduated with an MFA from Elam School of Fine Arts in 2012. She has recently exhibited at Artspace Aoteaora (2017), Te Uru Waitakere Contemporary Gallery (2017), at RM Gallery (2013 & 2016), Malcolm Smith Gallery, (2016), BREENSAPCE Sydney (2013), Sophie Gannon Gallery Melbourne (2014 & 2016, 2019), tcb Gallery Melbourne (2016). The social sculptural commission For the Love of Bees for Auckland City Council 2016-2019 is nominated for the International Award for Public Art, 2019.

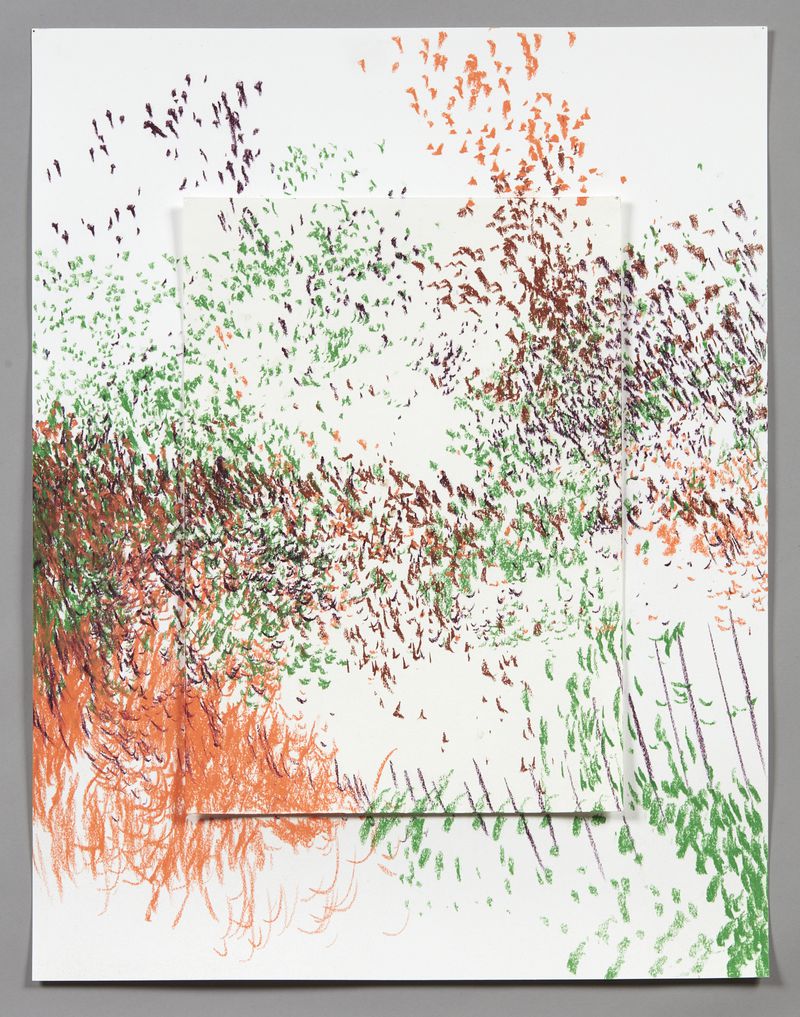

Sarah Smuts-Kennedy, Hearts Circuit-Event Within Boundaries, 2016

Sarah Smuts-Kennedy, Light Language, 2017

Toward the center of the field there is a slight mound, a swelling in the earth, which is the only warning given for the presence of the work.

– Roasalind Krauss, Sculpture in the Expanded Field, 1979

It’s a wretched day for writers and their texts when we hold them account for all those lives ahead of them. Those who have read and re-read their thinking – arguing against them for not anticipating a shift in terms, or a changed set of perceptions fresh for a new era. Almost forty years from its publication, American art historian Rosalind Krauss’ text ‘Sculpture in the Expanded Field, reads like a case against the conservative indictment of the new art forms of the late 1960s –the cry that really anything could be art now. To do this Krauss labours her now familiar structuralist diagram to adjust the terms of reference, and create for the humanities a logical and orderly explanation for the diffusion of modern form, support, viewer, architectural and landscape relationships.

The Klein diagram seems even now to offer some security for art’s expansion. If it is not this or that, then it is part of the field of terms established by their relationship in opposition. Yet most of these terms are known, even when they are read by their negative value, they are in, as Krauss writes, ‘the outer limits of those terms of exclusion’. But Krauss’s own terms could not have anticipated a kind of practice to lift off the field altogether as it were into the space of esoteric practice, where the ‘field’ is the unseen and unfamiliar field of energy – spiritual energy. A space where Sarah Smuts-Kennedy’s garden might not just be not- landscape/landscape or architecture/not-architecture or sculpture/not sculpture, but a place to work practically on that energy. How did we get out of the diagram? Or as Krauss might argue is this a re-deployment of the postmodern, in which we have reorganized the terms that are held in opposition within a new cultural situation. Esoteric practice arises, when the logic of ‘sculpture’ lets just say, even within the expanded field follows a too logical too familiar course. As my dictionary says the antonym of esoteric is familiar.

I might not have been thinking of Krauss even if I hadn’t been grappling with ‘the energetic field’, something Sarah Smuts-Kennedy has been working with since her completed post graduate exhibition. So you see even I am engaged in this dialectic, as I return the amorphous ‘energy field’, back to the frame of references established in this formative post structuralist text. So we’ve expanded the field in the only place left – the outer outer limit. Yet how helpful is this route? The implication that the growth of interest in ‘mystical’ subject matter or in this case energy fields was not more than an exercise in the expansion of terms, is a too- reductive or even cynical evaluation of the genuine attempts on behalf of an artist to explore the ‘practical exercises that help extend our ability to perceive the nature of things. To help us pay attention to the subtle perceptions that we often ignore, yet which offer opening to a world of form, dynamic patterns and colour and more intimate relationships to our feelings, thoughts and impulses.’1

In opening out her discussion Krauss begins with a description of a work by Mary Miss made the year prior, Perimeters/Pavilions/Decoys, 1978. Outlining the basic elements of the work as if from a distance, piecing together the scene in the landscape before closing in on definitions, Kraus names the work as ‘of course a sculpture or, more precisely, an earthwork.’ What I want to differentiate here for Smuts-Kennedy is how her own large garden north of Auckland, built using biodynamic processes, functions both outside of the work and as a basis for the sculptural work that would later emerge. The garden is not sculpture, or earthwork nor does it behave as her artistic practice, but in relation to her artistic practice it is the means for exercising the ideas basic to her practice which I might describe as – the exploration of forms which have the potential to practically influence energy fields and systems for productive outcomes.

Already in 1924 Rudolf Steiner’s biodynamic farming was responding to complaints of soil degradation by farmers and landowners in Germany. In many respects early organic farming was established internationally in response to the effects and impact of industrialisation. So, despite the practices derived from the more esoteric ends of Steiner’s early association with the Theosophical society, the emergence of his theory of agriculture was based in the modern period and its discontents.

It’s not so much of a stretch to compare other artists who have exercised their creative eye within the garden, including that most famous example of French Impressionist Claude Monet whose practice and his garden at Giverny emerged in the industrial era. Experimenting with colour relationships in nature while also cultivating his compositional interest in Japonism via the garden, Monet commented on the ‘magic’ of the garden, ‘I had planted them for pleasure; I cultivated them without thinking of painting them. A landscape does not sink into you all at once. And then suddenly I had the revelation of the magic of my pond. I took up my palette. Since then I have hardly had another model.’2 Here and elsewhere Monet describes what appears to be a symbiotic relationship between his cultivated landscape and the representation of it. But what to make of the presence of magic? The word occurs again at the end of the century in artist, filmmaker and writer Derek Jarman’s thoughts on his garden at Dungeness, England, ‘At first, people thought I was building a garden for magical purposes – a white witch out the get the nuclear power station. It did have magic – the magic of surprise, the treasure hunt.’3

At face value Smuts-Kennedy’s garden appears to function less as an aesthetic device and more as a tool or an instrument for exploring synergistic systems in biology. She herself has said, ‘biodynamics is a practical way to practice working between energetic systems and biological systems.’4 Sitting somewhere between a commercial or market garden and a domestic-scaled garden bed, this garden is designed to feed (it’s edible). Also it is in every sense hand reared, the original site was formed on a dense clay bed over which Smuts- Kennedy has built up a thick fertile soil. Here the word energy could be exchanged with work. During the process of the garden’s development and fertility Smuts-Kennedy was also undertaking postgraduate study focusing on the development of her sculptural form. In her first major exhibition in Auckland after graduation, Shape Analysis, 2013, she made highly polished bronze squares that hung elegantly from the ceiling using fine wire. Attached to each corner of the square frame the wires made light and airy cube and rectangular structures from the suspended bronze squares, which from a distance looked like she was drawing volumes of air itself. In the text for the exhibition Smuts-Kennedy wrote that the shapes were formed through the process of ‘mapping the room’s electro-magnetic field, such as telluric currents, man-made electrical currents and electro-magnetic radiation.’5 So the forms demarcate sites of electrical energy. These fields were identified with the help of a guide, but that assistant does not in any way designate or suggest the visual form for these invisible zones within the architecture of the gallery. In what might otherwise appear to be an extension of minimalist sculptural language, Smuts-Kennedy gives them a form but also a context within the field of art. Their sculptural ancestor appears to be closer to American Donald Judd than Robert Smithson and his great environmental works. Through his writing as much as his sculptural practice Judd still represents the height of sculptural Minimalism, despite his known resistance to the term. In an interview made the year after his first one man show at the Green Gallery, New York, Judd commented in what now seems like quite general terms about his intention towards a ‘simplicity’ that was also complex. Judd also defines simplicity by which it is not – it is non-naturalistic, non-imagistic and non expressionist. As he saw it, the geometry in the work which included the free-standing cubic forms for which he has become most known, is also disassociated from ‘Geometric art’. In fact Judd allowed for a kind of ‘obscurity’ in reading the work, something that was not so immediate for viewers, ‘I think what I'm trying to deal with is something more long range... more obscure perhaps, more involved with things that happen over a longer time perhaps. At least it's another area of experience.’6 However he denies the association with Mondrian, and he ‘orderliness’ or what he perceives to be a moral guide underpinning the work. In this way one reads the work is distinctly American. Mondrian was well known for his interest in Steiner’s anthroposophy and theosophical roots even in late twentieth century America and for Judd at least this was an alienating matter.

Sarah Smuts-Kennedy’s work undergoes something of a transition through the course of her residency at the McCahon House which magnifies this inversion of classic spiritualist traditions in art. In her description of the residency outcomes she proposed using the esoteric practice of Agnihotra to experiment with the healing of the Kauri trees surrounding the residency studio. These trees, the inspiration for some of artist Colin McCahon’s most defining early Auckland works, are now widely known to be grievously in danger from a soil borne disease. Facing the Kauri in their contemporaneous environmental condition Smuts-Kennedy practiced the Vedic fire ceremony and its healing mantra at dawn and dusk in a real-world experiment to heal the Kauri. Her actions were motivated not purely by Vedic science or spiritualism, but via the concerns of an artist operating with a fusion of healing systems for her resources.

Following on from Shape Analysis, and her work with electro-magnetic or energy fields, Smuts-Kennedy appeared to travel closer to Mondrian’s concerns for the spiritual in art. In particular in her exhibition Field Work she introduced threedimensional colour triangles and squares in overlapping geometrical forms. Taking the three-dimensions available to sculptural and architectural space Smuts-Kennedy appears to model diagrams or experimentations of Mondrian’s theory of plasticity in which composition, colour and line are employed in the representation of essential harmonies. However, curiously Smuts-Kennedy whilst using similar language is not pointing towards harmony, but in many respect a kind of disharmony. While the work both in its sculptural form and simplified colour relationships describes this harmonising impulse it is set in relationship to a natural field which is troubled, either with toxicity or erosion. In recognising what parts are in play here, we realise that Smuts-Kennedy has subtly inverted the principles of early twentieth century spiritualist tradition. Here, rather than art providing a representation of the unseen, or universal harmony in nature and let’s just say ‘spirit’ for want of a better word form and colour are used in an attempt to balance or even heal a disrupted field. Therefore the ‘art’ is a tool which has an implicit job to do in relation to what we might more commonly call our environment. But included within that environment is not just the natural world but its less visible properties.

Yet realistically how much can we separate the artist from her spheres of interest whether they are visible in the end result or not? Even Mondrian knew as much, when he reminded readers ‘art is a duality of nature-and-man and not man alone’. In her interview with Radio New Zealand’s notoriously sceptical Kim Hill Smuts-Kennedy skilfully argued that, ‘that’s the great thing about art work, it allows us to test and play with things we wouldn’t otherwise give credence to’7. So in much the same way that Joseph Beuys framed up his form of ‘social sculpture’ influenced by Steiner’s thinking art might be deployed to mould society, even having a direct real-world positive outcome. Beuys stated for example that ‘the concept of sculpting can be extended to the invisible materials used by everyone. That is why the nature of my sculpture is not fixed and finished. Processes continue in most of them: chemical reactions, fermentations, colour changes, decay, drying up. Everything is in a state of change’.8 Beuys offers a model of art’s relationship to society that interconnects esoteric thinking, something that has been mostly divorced from contemporary accounts of social sculpture. Following the residency Smuts-Kennedy also ran an agnithotra workshop at Auckland’s Artspace in association with her solo exhibition, which in the company of more traditional gallery visitor programmes was categorised as something closer to an artist’s performance. Far from the Titirangi trees now on Auckland’s Karangahape Road, the action had less ‘real-world’ implementation, but it was nonetheless utilised much like a teaching tool, to open out discussion on the trees and the energy field itself.

Smuts-Kennedy ran with several streams of activity in the studio during her McCahon House residency. One of these was the series of rhythmic drawings made using colour pastels drumming against the paper while it’s pinned to the wall in an almost meditative state. As she describes it the colour palette is selected by pendulum, and the almost hypnotic rhythm of the pastel’s application takes precedence over the artist’s conscious decision making. They are clearly abstracts made in a state of abstraction, yet the ‘high key’ to use Van Gogh’s phrase and the patternation are heavily reminiscent of the Impressionist’s relationship to the emerging science of colour. However these pastels are twenty first century tools and their colour range and capacity reflects the intricate developments in chemical colour, now long divorced from natural dyes and pigments. Yet the activity and integration of colours on the paper is highly active and intuitive. They are perhaps the most seductive of her works to date – why? Colour… to steal from Michael Taussig who in turn borrows from William Burroughs… appears to walk off the page. Whatever the mind/hand combination was that made these works, they seemed to know about the blending of light that occurs in certain colour adjacencies. In his essay ‘What Colour is the Sacred’, Taussig seeks to reinvigorate the investigations of early twentieth century social anthropologist Michel Leiris. In the course of the text understanding colour becomes analogous to understanding the bodily unconscious, ‘that which holds the future of the world in balance’. 9 He writes ‘ we need to catch up with the way that history turned the senses against themselves so as to control them. The mystery of color lies in the fact that it evaded this fate because, while vital to human existence, it could never be understood.’10 In the spectrum of examples he brings to bare on the problem of colour’s relationship to the sacred, Taussig nonetheless positions himself if not his examples firmly in the twenty first century’s problems and insights:

…the new nature of the new commodity world in which industry was gearing itself to fabricate cheap luxury goods. In mimicking nature, industry and most especially the chemical industry promised us utopias and fairylands beyond our wildest dreams, hence not merely colored, but magical, not merely colored, but poisonous. As the spirit of the gift, color is what sold and continues to sell modernity. As the gift that gives the commodity aura, color is both magical and poisonous, and this is perfectly in keeping with that view which sees color as both authentic and deceitful.

There can be no doubt that the drawings point us into nature, with or without the remembered history of pointillism and impressionism. Their likeness to colour in motion is most certainly of our world, they have wind and weather and seasons even. They move off the page like a living thing and motion towards the window. If there is deceit in this action, it is peaceful and accepting. The world has been wronged, we no longer trust or delight in rainbows, we’re thinking about pollution and pathogens in the atmosphere. Even as children are the last to delight in colourful magic within ancient intensity, they are taught about the ozone hole.

The drawings have been built in rapid development, and rather than essentialise colour relationships they are open to the viewer’s own perceptual movements. In the span of the artist’s practice they are also the most recent in a series of inversions within which she situates her three-pronged hand – art, the healing tool, nature. This time one can’t help feeling what we have in front of us is something like Monet’s cosmic garden represented for us, to stimulate our own need for healing as it did for him at Giverny and Jarman and Dungeness. However they are not explicitly ‘in nature’, whilst our relative consciousness may situate us there, these are without doubt representations of the inexplicable. They are allegories of a hopeful state, whether in wo/man or nature. Our responses to them are remote from logic but somehow engage the space between science and art. The colour field depicted comes as close as SmutsKennedy has yet to the representation of that unfamiliar space – the field of spiritual energy. Yet what of the white page? Is it enough? My sense is that this artist will keep recasting her pyramid of intentions until she finds the balance of the bodily unconscious which directs her one way or another into art and life on the case of nature. Unlike the modernists she is under no illusion that we can escape the chemical pollution that has now altered our natural world and atmosphere. Instead, through social and formal mechanisms, she proposes that within art we might at least imagine it differently (which in this instance is analogous to imagining the unthinkable) in order to start productively affecting change.

Essay commissioned by the McCahon House Trust on the occasion of Sarah Smuts-Kennedy's residency and resulting exhibition Light Language, 2 September – 29 October, 2017 at Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery

- Notes from the artist’s journal 2017

- Claude Monet cited in Jacqueline and Maurice Guillaud, Claude Monet at the time of Giverny (Paris, Centre culturel du Marais: 1983) p.150.

- Jarman, Derek, in Derek Jarman’s Garden (London, Thames and Hudson: 1995)

- Sarah Smuts-Kennedy in conversation with the author, July 2017.

- Sarah Smuts-Kennedy, in http://sarahsmutskennedy.com/project/shape-

analysis-rm/ accessed 27 August, 2017 - Donald Judd, in an interview with Bruce Hooton on February 3, 1965 for for the Archives of American Art, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-

history-interview-donald-judd-11621 accessed 27 August, 2017. - Sarah Smuts-Kennedy in conversation with Kim Hill, http://www.radionz.co.nz/national/programmes/saturday/audio/201852032/ sarah-smuts-kennedy-kauri-and-mccahon accessed 27 August, 2017.

- Joseph Beuys in John F. Moffit, Occultism in Avant-Garde Art: The Case of Joseph Beuys (1988: UMI Research Press, Michigan), p.109.

- Taussig, Michael, ‘What Color Is the Sacred?’, in Critical Enquiry, Autumn 2006, p.32

- Ibid., p.32

Artist Artworks

Sarah Smuts-Kennedy

Sound of Drawing: beginning, middle, end March #2

2017

digital print on Hahnemuhle photo rag paper, edition of 3

triptych, 420 x 297mm each

Collection of McCahon House Trust

Sarah Smuts-Kennedy

Sound of Drawing: beginning, middle, end March #1

2017

digital print on Hahnemuhle photo rag paper, edition of 3

triptych, 537 x 420mm each

$1,400 (unframed)

Contact us to purchase this edition.