- Amy Howden-Chapman2014

- Ana Iti2020

- Andrew McLeod2007

- Andy Leleisi’uao2010

- Anoushka Akel2024

- Ava Seymour2009

- Ayesha Green2022

- Ben Cauchi2011

- Benjamin Work2024

- Bepen Bhana2016

- Campbell Patterson2015

- Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss2021

- Dan Arps2014

- Daniel Malone2014

- Emily Karaka2021

- Emma Fitts2018

- Eve Armstrong2009

- Fiona Pardington2013

- Gavin Hipkins2007

- George Watson2024

- Glen Hayward2011

- Imogen Taylor2017

- James Robinson2007

- Jess Johnson2019

- Jim Speers2010

- Juanita McLauchlan2025

- Judy Millar2006

- Kathy Barry2012

- Lisa Reihana2009

- Liyen Chong2012

- Louise Menzies2016

- Luise Fong2008

- Madison Kelly2024

- Martin Basher2010

- Matthew Galloway2025

- Michael Stevenson2023

- Moniek Schrijer2021

- NELL2023

- Neke Moa2023

- Nicola Farquhar2018

- Oliver Perkins2017

- Owen Connors2023

- Regan Gentry2012

- Richard Frater2020

- Richard Lewer2008

- Rohan Wealleans2008

- Rowan Panther2025

- Ruth Buchanan2013

- Sarah Hudson2025

- Sarah Smuts-Kennedy2016

- Sefton Rani2025

- Sorawit Songsataya2018

- Steve Carr2020

- Suji Park2015

- Tanu Gago2022

- Taro Shinoda2017

- Tiffany Singh2013

- Tim Wagg2019

- Wayne Youle2019

- Zac Langdon-Pole2022

- Zena Elliott2026

Anoushka Akel

YEAR OF RESIDENCY

January - April 2024

Parehuia Education Resource: Anoushka Akel, 2024

Anoushka Akel is an artist who lives and works in Tāmaki Makaurau. She received her MFA from the Elam School of Fine Arts in 2010. Akel works across the mediums of painting and printmaking engaging with various fields including: art history, neuroscience and psychology, embodied poetics and philosophies of care. Her work considers pressure and plasticity in relation to a body, behaviour, and the art object.

Akel has exhibited extensively, featuring in shows at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, Hopkinson Mossman, Artspace Auckland and Michael Lett; with whom she also held a solo exhibition at the Aotearoa Art Fair 2023. Anoushka has presented work at TCB, Melbourne, Goya Curtain, Tokyo, and was the recipient of the C Art Trust Award in 2018 and artist in residence at Künstlerhäuser Worpswede, Bremen, Germany in 2013.

Images

Top: Courtesy of Michael Lett

Profile: Meg Porteous

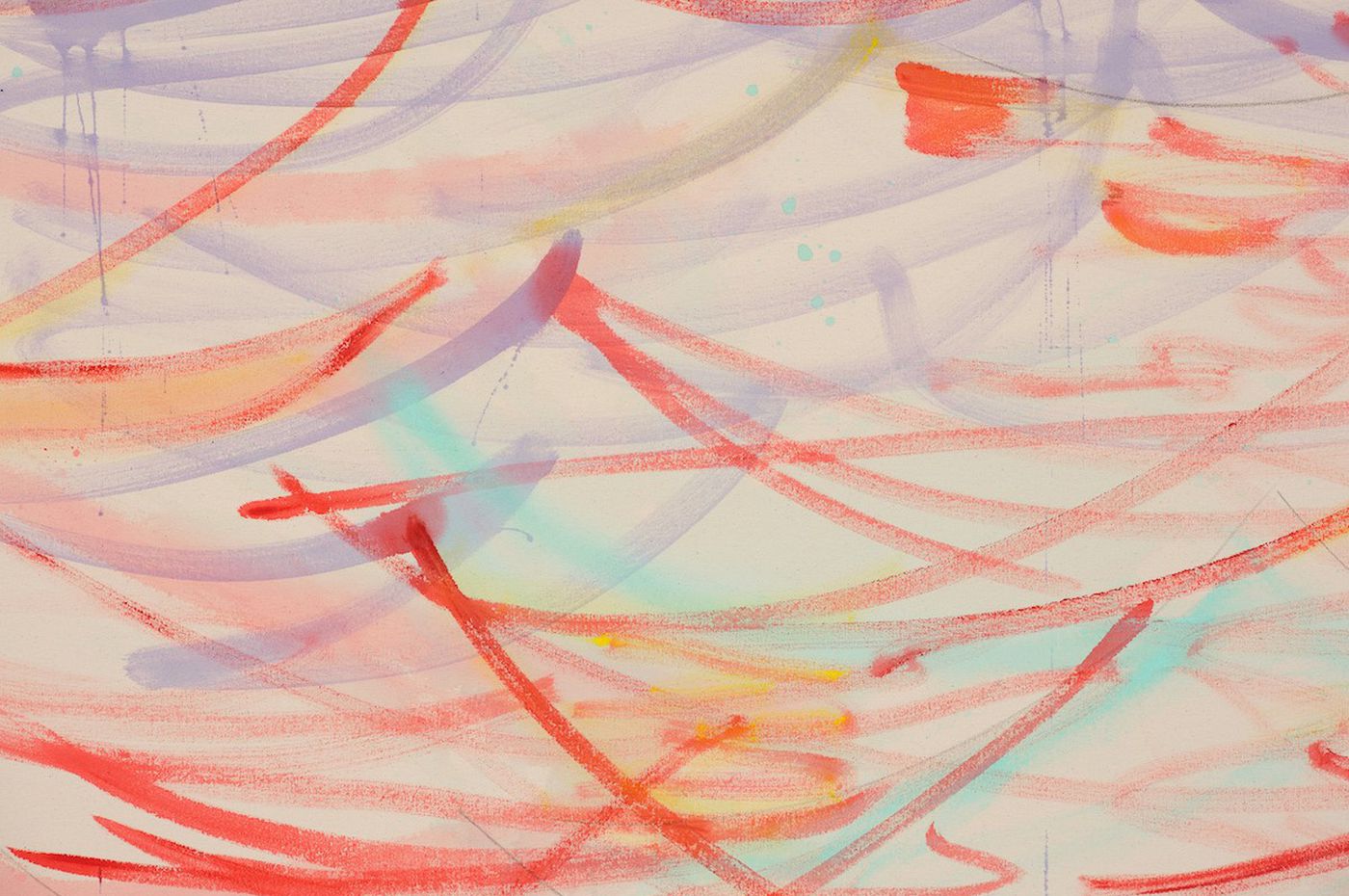

Anoushka Akel, Commune, 2024, Oil, acrylic and charcoal on canvas, 1500 x 3000mm (triptych, each panel 1500 x 1000mm) Installation view, Michael Lett, Karangahape Road. Image courtesy of Michael Lett

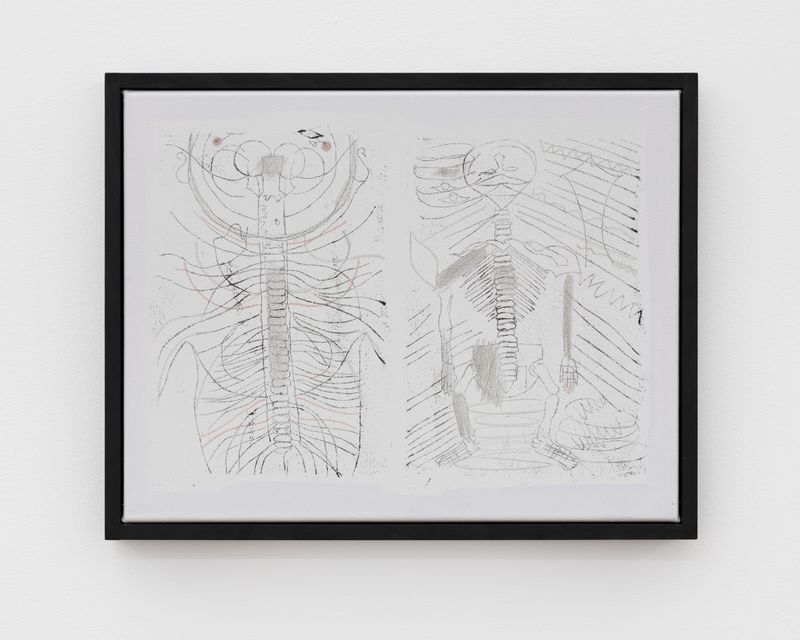

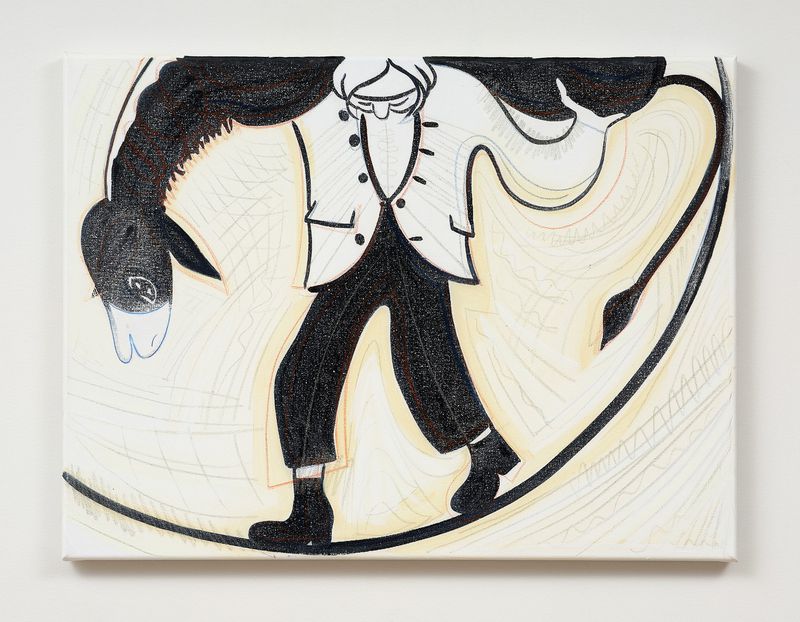

Anoushka Akel, Anatomy Museum (Mansur), 2024, Oil and oil pastel on canvas, 376 x 480 x 30mm frame. Image courtesy of Michael Lett

Anoushka Akel, Anatomy Museum (Mansur), 2024, Oil and oil pastel on canvas, 376 x 480 x 30mm frame. Image courtesy of Michael Lett

Anoushka Akel, Commune (green), 2024, Oil on canvas, 660 x 1060mm. Image courtesy of Michael Lett

Anoushka Akel, Arterial Sun, 2024, Oil on canvas, 670 x 1015 x 25mm frame. Image courtesy of Michael Lett

Last summer, I discovered a wasp’s nest on my front porch. It was about the size of a grapefruit, teeming with busy wings and legs. Daniel and I watched it get larger for a while, revelling in the sublime, hesitant to get close. Eventually we destroyed it with some kind of toxic spray and it promptly shrivelled up and fell to the ground before our eyes. Days later I happened to read about the role wasps played in the development of modern paper. Written records describe the story of T’sai Lun, a court official in 2nd century China, who lay beneath a tree watching wasps strip the bark from the branches above. As he observed closely, he discovered they were dissolving the wood to a pulp with their saliva and spitting it back out to form the cells of their nests. Wasps are an invasive species in Aotearoa, but they join countless beings—human and non-human, known and obscured—who have given something, or been taken from, to shape the world we know. In this case, the ability to record.

As I write today, arborists are clearing a section of native bush beside the room where I work. 80-year-old kānuka are being dismantled branch by branch and put through a wood-chipper. An ecologist, a gentle giant of a man, surveys the treetops for nests and the ground for lizards, rescuing a giant centipede furled around her eggs. As the trees come down and their inhabitants disperse, I think through Anoushka Akel’s recent series of paintings, Carrying the Beast.

*

One of this show’s smallest works, Anatomy Museum (Mansur), depicts a squat, strange skeleton. It is a re-drawing of an image by a late 14th century Persian physician, Mansur ibn Ilyas, who made what is believed to be among the earliest colour manuscripts of anatomical drawings, and one of the first of those to feature a pregnant woman. This early record of Middle Eastern medicine is referenced within a grave context. Anoushka has been painting, and I write, at a time when Arab lands are being systematically erased: crowded hospitals bombed, universities and libraries destroyed, food and water withheld, lives abandoned by those with the power to protect them.

Mansur’s drive to map the human body is a poignant counterpoint to such barbarism. Of course modern medicine has its own barbaric legacy, but I am also reminded of the centuries of care and research that have gone into acquiring and passing on knowledge in order to preserve life. The proportions of this body, rudimentary as they seem, feel truthful to the essence of a being, to the basic quest of art and medicine to understand and help one another, ourselves. The primal shapes of eyes and noses double and float out as though seared into the retina of a curious soul who is repeating, grasping, remembering.

In an email from Parehuia, Anoushka ruminated on the fraught history following her grandfather’s emigration from Lebanon during WWI. Perhaps her family would have contemplated a return to his homeland if not for the Nakba of 1948, which pushed Palestinian refugees into Lebanon and bred violent divisions. As it happened, Anoushka’s grandfather, Richard Akel, ended up devoting his life to medicine as a respected paediatrician in Whakatāne. Surprisingly, he is also where Anoushka found a connection to Anne McCahon (née Hamblett), Colin McCahon’s wife. When Richard was undertaking his medical training at the Otago Medical School, Anne, who was exactly his age, was also employed there to draw medical specimens (aligning her, also, with Mansur). This serendipitous crossing of paths back in time offered Anoushka an opening to commune with Anne as one of her ‘art grandmothers’.

As Anoushka deep-dived into the archives at McCahon house, she would find that illustration continued to be Anne’s bread and butter. Like many women artists and writers of her time, Anne used the medium of printed matter as a way to sustain a creative practice from the confines of her domestic world. With four children and Colin’s income sporadic, Anne took illustration commissions for The New Zealand School Journal to support the family throughout the 1950s and 60s. Anne had been an accomplished painter, but as Linda Tyler surmises, made “a conscious decision not to compete with Colin,”1 and found fulfilment in other work. While Anne’s story is not simply one of a disenfranchised wife, I struggle to imagine how she could have decided on anything else. With Anne’s School Journal drawings forming the centrepiece, Carrying the Beast points to the work women produce in less visible places, to the support column they so often form in families and societies.

*

Anoushka’s paintings have long been attuned to the workings of female and maternal care. I think of a piece I saw last year, :( Johny, which references a drawing by Sofonisba Anguissola—one of the Renaissance period’s few female painters—and her acute attention to a moment of pain as expressed and beheld by children. In her re-drawing, Anoushka carries the alarm and heat of the original into doubled lines of eyes, ears, and noses, energetic swarms of paint mimicking ink pen scribblings. I think, too, of the studies she showed me early on in her residency, when she was finding her bearings for this body of work. One was a charcoal re-drawing of a Käthe Kollwitz pencil sketch, in which a sleeping or ailing child’s head is cradled in their mother’s hands. “Each evening when I kiss my daughter goodnight,” Anoushka wrote, “I think of how peace is never a given.” Indeed, Kollwitz lost a son, and later a grandson, to two world wars. Her unflinching attention to women’s grief, work, and working-class survival would inspire Muriel Rukeyser’s famous lines: “What would happen if one woman told the truth about her life? / The world would split open.”2

These world-splitting yet mundane truths are what Anoushka is often drawn to. After the Kollwitz study, Anoushka showed me more drawings: a large pastel self-portrait as she combs through her daughter’s hair for lice, front-facing and Madonna-like; a re-drawing of a Kippenberger painting in which the artist’s mother balances a pile of stones in her arms (an uncanny echo of the stacked vertebrae in Anatomy Museum), the largest stone held high as she looks at it sidelong. Much is symbolically held by these maternal figures and their full hands. I am reminded of Jacqueline Rose’s troubling question: “What are mothers being asked to carry, what forms of failure and injustice are they made accountable for, above all, in the modern Western world?” Beyond examining the sociopolitical, literary, and historical measures of this weight, Rose looks to the transgressive borderlessness of motherhood “as the foundation for a different ethics and, perhaps, a different world.”

To re-make the works of others is also to permeate artistic borders: communing directly in tracing past gestures and subjects; insisting on the creative necessity of mimicry and a transparency of influence and process. The individual becomes more difficult to define. It is also a form of caretaking, preservation, and even resurrection, ensuring the continued spiritual presence of the particular images she transforms. Perhaps this impulse stems from Anoushka’s experience in art conservatorship, a field she gained experience in over her years working for the Melbourne Museum. As I sat in her studio a month before the opening of her show, Anoushka stood carefully wiping small areas of paint from the surface of a work. This is a part of the process she enjoys the most, she told me, when the painting has become a kind of ‘body’ she can attend to. That patina of care is visible in the layered colours and marks of works like Your Sea, where ghosts of boats and birds hover beneath the waves, testament to (and inviting) revisitations.

*

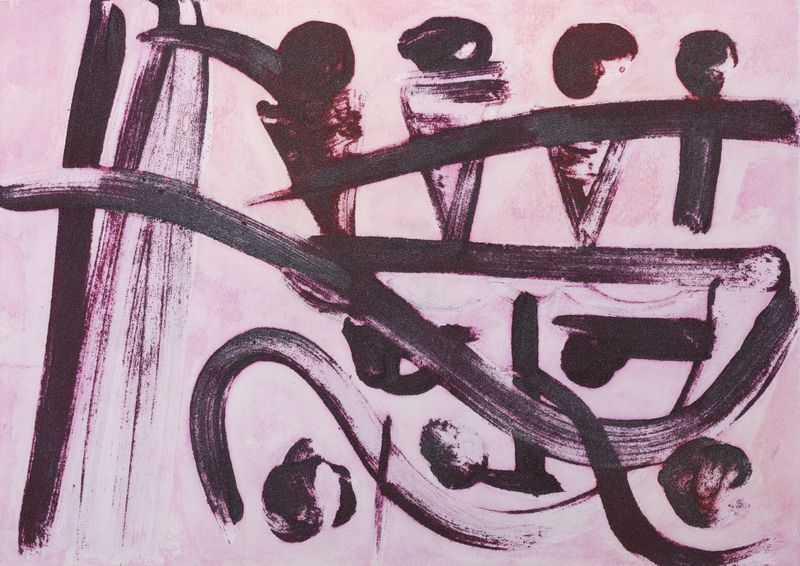

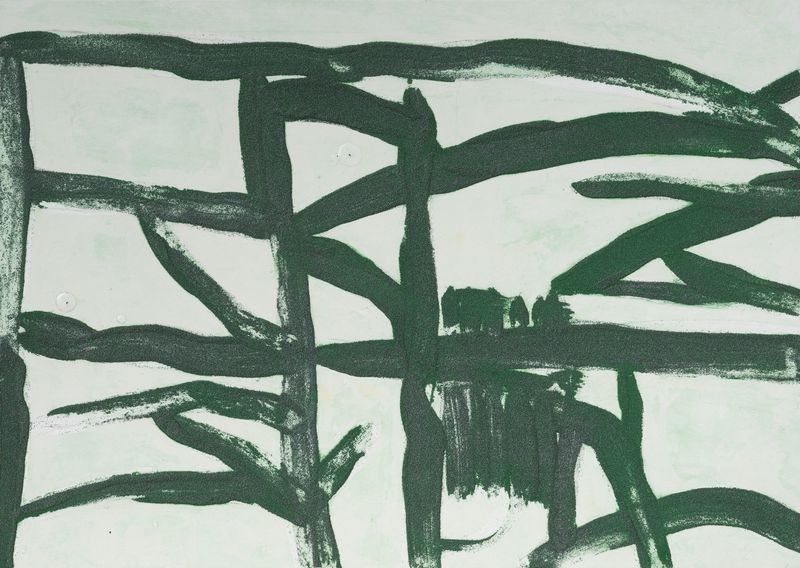

As scenes from Gaza reached her leafy enclosure at Parehuia, Anoushka found herself returning to Etel Adnan’s The Arab Apocalypse (1989) to make some kind of sense of the senseless. Adnan’s poem is a breathless, revelatory epic, her words erupting into glyphs as language reaches its limits in bearing witness to the horrors of the Lebanese civil war. She had set out to write a simple poem about the sun, but as the siege and massacre of Tel al-Zataar unfolded in Beirut, that sun mutated into a symbol for the ferocity of empire. Barely a page in the poem goes without an iteration of the sun, which seems to consume everything in its path, “destroying and destroying until it eats itself, as all empires are destined to do.”3 A red sun a blue sun a green sun a yellow sun: this cumulative poem is perhaps a formal influence for the colours and repetitions of Carrying the Beast, the tree-lines and title of Commune reappearing in silver, gold, and green, and their vascular forms again in Arterial Sun.

Alongside Etel Adnan, Anoushka was reading about the nurturing networks between trees, surrounded as she was by the lush tangle of native forest. She wrote to me of the ways they look after each other, tending to the sick and sending chemical signals to warn neighbours of threats. Paintings of these communities took shape: brisk, flat works on loose swaying canvas, almost reminiscent of theatre backdrops (set design was another of Anne Hamblett’s early jobs). These works take their larger scale from McCahon’s 100 x 750cm Teaching Aids and political posters. But rather than the vertical trunks of McCahon’s kauri paintings, or even the stark unseriffed ‘I’ of his ‘I Am’ paintings, here branches form a web of horizontal bridges—not unlike inner bone tissue, to circle back to Anatomy Museum again—in which the individual loses distinction. Lines grow across as well as upward, limbs that may hold whatever might come to land.

We look to native ecosystems for a true commune, and commons: one in which nobody’s freedom is theirs alone, or contingent on the oppression of another. In the Commune paintings, that ruthless sun is for a moment held, its fire defused by the thicket of trees (McCahon famously found the kauri forest claustrophobic after the open plains of the American midwest). Layers of light pass through, filtered in varying degrees: trunks and branches are sometimes blocks of solid colour, more often semi-transparent washes housing darker layers behind and within, their edges bleeding into the porous canvas. We do not see the tops or bottoms of these trees; instead we are at the level of a creature who inhabits them. Which was once, after all, what we were. According to evolutionary theory, tree branches are where we developed the capacity as small primates to grasp and hoist ourselves up through the canopy. For better and worse. They are an origin point of our own hands and branching fingers, and thus in another sense of the exhibition’s driving verb, to hold.

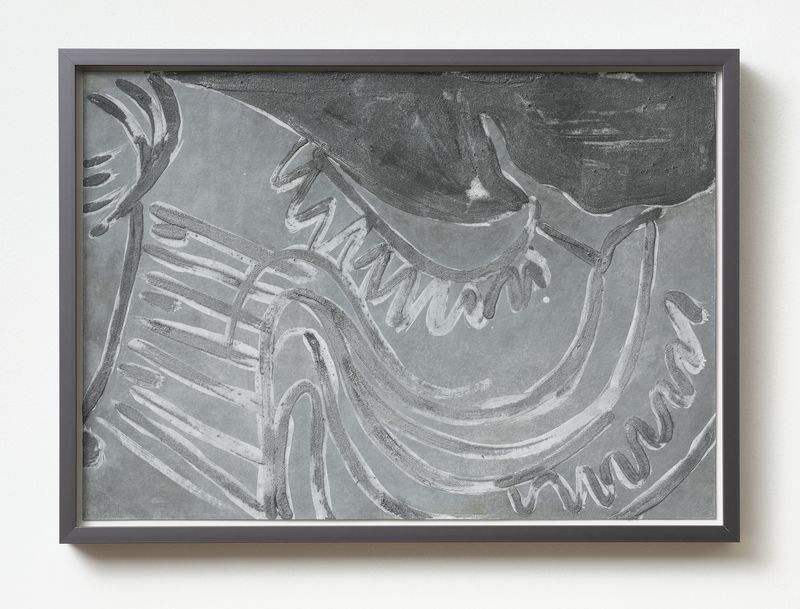

The repeated painting of the figure and donkey is another place Anoushka teases out this verb. It is a reworking of one of Anne Hamblett’s illustrations for a story called Lazy Jack, in which a solo mother attempts to instil some common sense in her son and enlist his help with domestic labour. Jack is sent to fetch goods from the market, but time after time fails to bring them home in one piece due to his failure to transport them wisely: his mother’s advice seems to backfire on her each time. Their fortune finally changes when, after bringing home a leg of lamb he has spoiled by dragging it along the ground, Jack’s mother gives him the advice to ‘next time, carry it home on your shoulders.’ When he then acquires a donkey and sets off (you guessed it) carrying it home on his shoulders, he captures the attention of a depressed young princess who is taken by the comic absurdity of the gesture. The rest is surmisable.

In the context of the Lazy Jack story, this final image highlights a striking contrast between son and mother, modernist men and women, (and to me, Colin and Anne), and their respective passages to prosperity. Jack never really needs to learn the lessons his mother was trying to teach him, for he wields another type of power out in the world. But he does marry into royalty and, the story assures us, supports his mother for the rest of her life. Beyond the story’s politics or even any kind of symbolism within the donkey, this remains an image of an intersection between extrinsic power and intrinsic strength. In their radical inversion, the expected relationship between the two is exposed and undone, prompting a sense of possibility: that which has long been held is suddenly, impossibly, holding.

*

Anoushka is attuned to her materials on many relevant levels. To their origins and politics (the mad king’s murex snail and its imperial purple), but also to the organic and microscopic, to porous surfaces that bear traces of water, fire, touch. When looking at framing options with maker Grant Bailey, Anoushka learned of a technique called yakisugi, a kind of controlled damage whereby the wood’s surface layer is charred to form a seal against mould, fungi, and water. This gesture of safeguarding felt pertinent to the medical subject of Anatomy Museum, and formed a reference point for the work’s blackened frame. Instead of burning the wood, Anoushka purposefully painted it with carbon black, an opaque pigment made from charred plant matter. Beyond merely framing the painting, this wood and its fortifying outer skin speaks deeply to the notion of protection.

Another layer emerges in one of the Carrying the Beast paintings, subtitled ‘(Lignin)’, which is an important molecular structure in the cells of plants and trees that ensure water and nutrients can be transported through their tissue. A kind of backbone, without which they would go floppy. While lignin is extracted from high grades of paper, it remains in the fibres of mass-produced pulp and is what causes the distinct yellowing over time as it oxidises. Perhaps this particular iteration of Carrying the Beast—its pale yellow halo and animated pastel lines pulsing round and through the figures—suggests those unseen architectures that hold our world together. Perhaps we see those same lines dance inside the blue branches of Arterial Sun, around the bones of Anatomy Museum’s skeleton. The lignin or nerves within.

In a process akin to printmaking, Anoushka will often soak the canvas in water before painting, allowing the weave of the canvas to expand and hold the paint inside rather than merely on top of it. By scrunching the canvas and then smoothing it out again she creates a “network of creases,” building a ground that is, like yakisugi wood, “damaged but strengthened.” For the paintings in Carrying the Beast, Anoushka worked more often with dry canvas, but this carrying capacity of plant materials was still very much in her thoughts. An earlier version of the exhibition title was longer: She is in the Ink and Paper, Carrying the Beast. When I asked what drew her to these words, Anoushka said she had been thinking of publishing as a structure that holds ideas, fixing their fluid forms within the pulp and carrying them across time. As Le Guin put it, “a book holds words, words hold things. They bear meanings.” It is the printed matter of art forebears that reaches Anoushka. Anne and Etel, each enabled to place weight somewhere it would stay and disseminate, their definitive lines and marks bearing very different lives. I think how the paper is, though so far removed from those original wasps, still a kind of nest.

1 Morton, Frances. ‘The Power of Two: The Woman Behind Colin McCahon.’ Metro, November 2016. 2 Rukeyser, Muriel. ‘Käthe Kollwitz’. The Collected Poems of Muriel Rukeyser. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2006. 3 Farah, Summer. ‘From Witness From Speech From Image: On Etel Adnan’s The Arab Apocalypse and Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee.’ Poetry Northwest, April 2024.

Artist Artworks

Anoushka Akel

Mad King Murex (1)

2025

Carborundum, polyvinyl acetate, primal and oil on cardboard

297 x 420mm

$2,000 (unframed)

Photo: Sam Hartnett

Anoushka Akel

Commune (1)

2025

Carborundum, polyvinyl acetate, primal and oil on cardboard

297 x 420 mm

$2,000 (unframed)

Photo: Sam Hartnett

Anoushka Akel

Carrying the Beast (1)

2025

Carborundum, polyvinyl acetate, primal and oil on cardboard

297 x 420mm

Collection of McCahon House Trust

Photo: Sam Hartnett