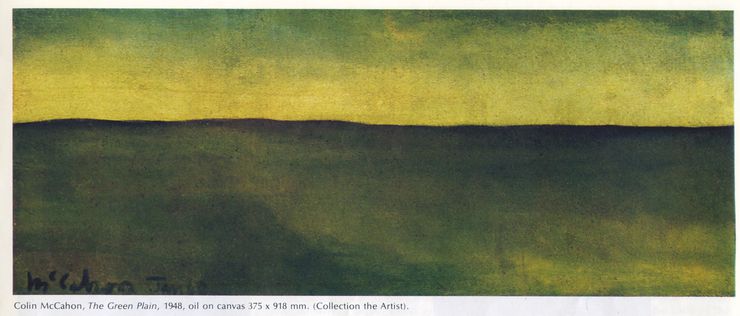

The Green Plain

The Green Plain, 1948, oil on canvas, 374 x 917 mm. Private collection, courtesy McCahon Research and Publication Trust

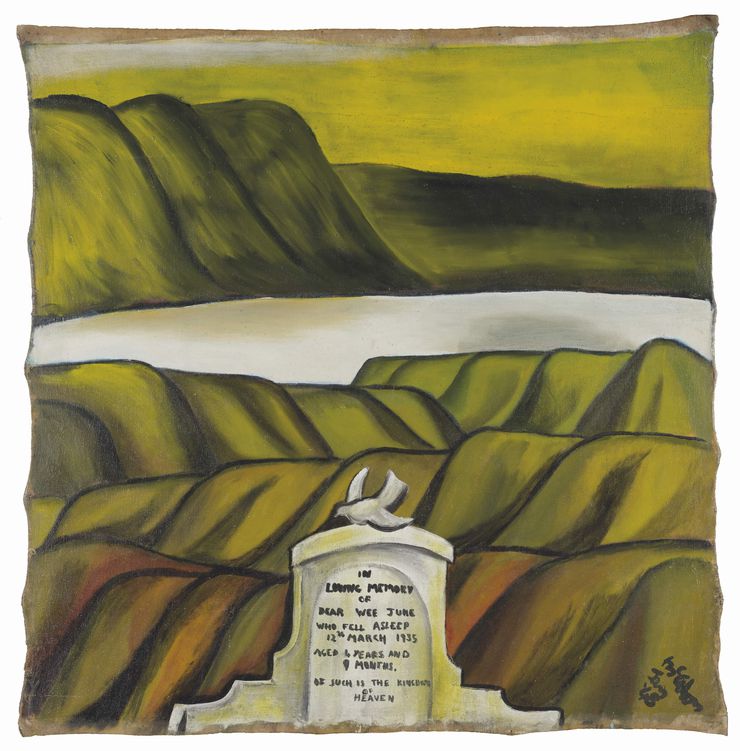

Dear Wee June, 1948, oil on canvas, 910 x 910 mm. Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hakena, University of Otago, courtesy McCahon Research and Publication Trust

Six days in Nelson and Canterbury, 1950, oil on canvas on board, 885 x 1165 mm. Collection of Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, courtesy McCahon Research and Publication Trust

Wystan Curnow

'The Green Plain' (or this text) will be published almost 60 years after my first McCahon publication, a review of the Gate paintings at The Gallery, in Symonds St in 1961. Since then there have been catalogue essays, exhibitions, lectures etc., on and on... but no book. I'm taking care of that at the moment.'

I’d been listening to Ray Thorburn’s 1976 interview, McCahon’s voice bringing him to life again, as I knew it would. He has such a lovely soft, light voice, now and then broken by a once-was-nervous giggle, yet he responds so succinctly, without hesitation or qualification. He has the confidence of someone who really knows his own mind. This was in the Research Library at Auckland Art Gallery. Soon enough it was closing time and on my way out I bumped into senior curator Ron Brownson. He is the only member of the Gallery’s staff who goes back almost as far as I do. Since mention had been made of The Green Plain (1948) on the tape, I recalled for him my earliest memory of it: it hung above his desk in the Research Library back when he was in charge. I visited the library quite a bit then, and grew familiar with and fond of it. Turns out it was only on loan, and has since left the Gallery. Still I had a question for Ron: the colours of the reproductions of The Green Plain in Justin Paton’s and Peter Simpson’s new books differ, which is closer to the original? I reckoned the Simpson, what did he think? He later emailed he reckoned the same. It’s great you can see the canvas weave, brushstrokes, and paint layers. For that reason the Paton image was the better for not being ‘clear cut’.

Leaving the gallery I crossed Kitchener and Lorne Streets, took the escalators down to the Citylink stop on Queen. As the crowded bus pulled up who should arrive but Ron. So, straphanging our way up to K.Rd., we resumed our conversation about The Green Plain. Ron noted its scale was much larger than its size, like some of the small Jump canvases. I agreed. As do Simpson and Paton: it is not a large painting, 373cm x 917 cm, but both reproduce it at about half its actual size. (Otago Peninsula (1946-49), by comparison, which also gets a double page, but in actual size is well over twice that of The Green Plain.) Reproductions aside, the painting feels bigger than its size because the proportions of both the canvas itself—it is more than two and a half times wide as high—and the unbroken horizon pictured on it, work together to optically stretch out the work’s lateral extent. Its panoramic reach. I said to Ron I wondered if there’s a connection between McCahon’s left-handedness and his use of text. I said, as a left hander myself, it seems natural to me that lines of print or handwriting begin on the left, whereas for right-handers ….? I asked Ron if he was left-handed. No, he replied, he wasn’t, but he had made quite a study of left-handedness in artists and writers, and didn’t doubt its significance. It sounded like he had plenty more to tell, but we’d reached our stop.

Ray Thorburn is an abstract painter—he has works in Te Papa’s and Auckland Art Gallery’s collections—so I’m not surprised he should ask about The Green Plain which is as abstract as any of McCahon’s paintings to that date. McCahon’s response is positive: ‘It was a discovery, at the time, it was a real discovery.’ But of what? Thorburn has asked what he’d gained from conversations with the painter Mary Cockburn Mercer—this was during his 1951 Melbourne trip—about her attitude to painting, to art. Her view was that art ‘had to be about something, and not just a vase of flowers or a landscape or a portrait, there is another layer that has to go into a painting before it ticks over’. Elsewhere he says to Thorburn his ‘landscapes are not landscapes.’ We should dwell on that briefly, because when The Green Plain was painted the vast majority of paintings exhibited in New Zealand were just one of those, that’s to say the genre answered the question: this a portrait of the artist’s mother, this is a landscape of the Southern Alps. Today’s art is rather different, art tends to be about ‘issues’, the other layer, supposedly deeper, is front and centre. You can say, The Green Plain is between landscape and abstraction (‘abstract’ is not a subject genre), and that many, subsequent McCahon’s occupy that place. Its ‘simple division’ he says,’ is one I’ve used ever since.’

Some see The Green Plain as the first in a series of Canterbury landscapes that culminates three years later in On Building Bridges (1952), but not me. For me the abstractness, the ‘plainness’ if you like, doesn’t so much topographically particularize Canterbury as simplify and defamiliarize landscape in the name of something else. That something else is Time, which is going to become an abiding subject. Time, and our consciousness of it, is what makes The Green Plain tick over. The time of day, as night turns into day, or day into night. When the light becomes strange and appearances change. Our attention is drawn to the horizon, more than just a division between earth and sky, it becomes a threshold, the divide between light and dark, past and present, beginning (sunrise) and end (sunset) of the world’s visibility. As day dawns—as I think it does here—the greenness of the plain comes to light. This horizon transcends the particularities of place, suggests a psychological and a metaphysical division, and so enters the same discursive realm as the biblical paintings.

Or does night fall? Change, even when it’s for the better, is a bearer of uncertainty—isn’t there a tinge of menace to The Green Plain? Not allowing landscape just to be ‘landscape,’ subjectifying it, has dangers. There's a price to be paid for over-reading the landscape, for expropriating that other layer of meaning from it. In a letter to his friend, Ron O’Reilly, McCahon reflected on this process: ‘… the landscape turns & rends you. Or is it only my experience (,) I may try to extract too much [?] I can’t express enough but I do do violence to the land and then suddenly I don’t know it any more … and if I can find enough love and reverence for the plains I may escape.’1

McCahon’s works speak to each other, they join in a conversation with their peers, which is ongoing. When Thorburn asked about Six Days in Nelson and Canterbury (1950), McCahon said: ‘can you see the connection with that and The Green Plain, which came before it? And its just an elaboration, a building up of the themes … it’s much more The Green Plain approach than it is anything else. It was a past and a present if you like, it’s a time sequence … getting rid of Nelson and coming to grips with something else.’ We can see how Six Days multiplies The Green Plain, expanding its temporal and geographic reach, how Takaka: Night and Day replaces its panorama with a bird’s eye view. Themes are added, each day is a revelation. Each word has an inflection that alters the conversation. God used this time frame for making the world. Comic books turn such sky lines into a journey, a series of events, a story line. It’s the gravestone inscribing June’s brief four years and nine months lifespan that makes Dear Wee June’s (1948) landscape tick over. A painting full of McCahon’s love and reverence for the landscape.

- The letter Colin McCahon to Ron O'Reilly is dated 19 January 1949. It is quoted with the kind permission of Mathew O'Reilly. The moral dilemma is inherent in Romantic epistemology, see Wordsworth's brilliant 'Nutting.'