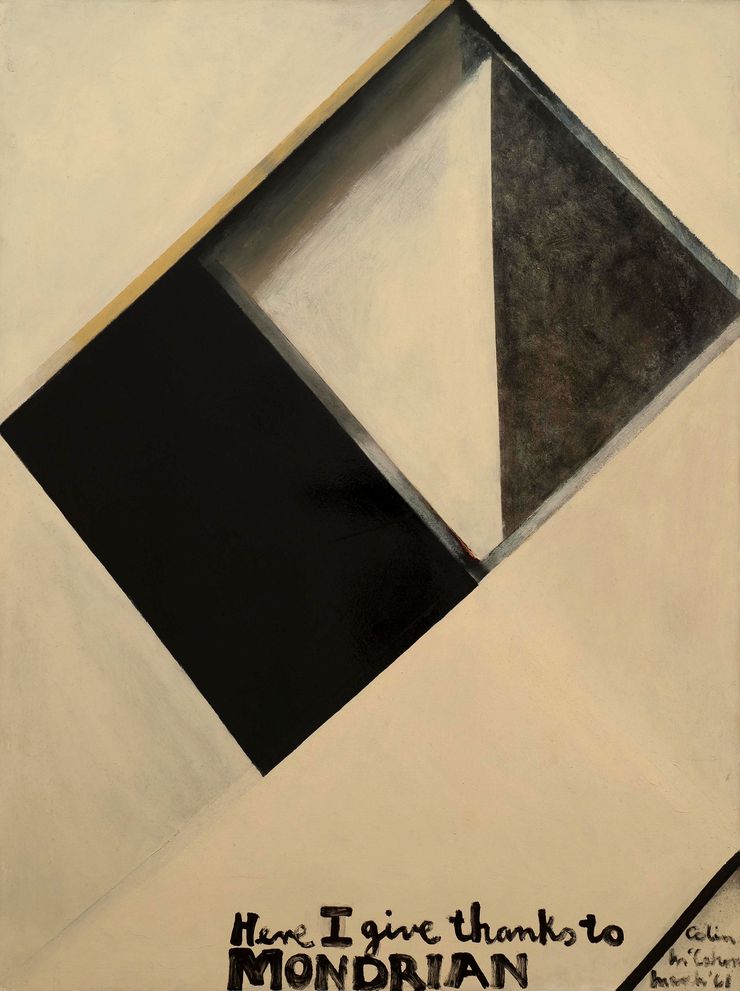

Here I give thanks to Mondrian

Colin McCahon, Here I give thanks to Mondrian, 1961, enamel on hardboard, 1215 x 915 mm. Courtesy Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki and McCahon Research and Publication Trust.

Billy Apple, Tāme Iti and Donna Awatere inside Te Ranimoaho with the installation of Apple’s Basic Needs translated into Te Reo Māori. Ruatoki, 2019. Image courtesy of Hamish Coney

Hamish Coney

I first saw this painting as a schoolboy in the mid 1970s. I can still recall its location in a small gallery upstairs on the southwestern corner of the then Auckland City Art Gallery, overlooking the Auckland Library and the Civic Theatre. My recollection of encountering Here I give thanks to Mondrian (1961) for the first time is still, after more than forty years, filed in the section of my brain titled ‘great art experiences’. It will always remain a ‘top tenner’ in that file along with: Carlo Scarpa’s Brion Tomb near Treviso in northern Italy, Francesco Borromini’s San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane in Rome, the whare whakairo Houmaitawhiti carved in the 1870s by Wero Taroi (Ngāti Tarawhai) on the shores of Lake Rotoiti, the Rosalie Gascoigne survey at the 12th Sydney Biennale in 2000, the Emma Kunz Cave and Museum near Zurich, The Joseph Beuys installation at Dia Beacon in upstate New York, a 1980s excursion to Pesaro in Italy to see Giovanni Bellini’s 1470s altarpiece, a recent trip to Ruatoki to document a collaboration between Tāme Iti and Billy Apple; and most recently witnessing McCahon’s own Gate III in all its glory at Te Uru in Titirangi just a few weeks ago.

That list includes many architectural masterpieces or in the case of Houmaitawhiti, the Borromini church and the Emma Kunz Cave, 360-degree experiences in the round. I’m drawn to artworks that house, hold and embrace you from all angles.

Here I Give Thanks to Mondrian (1961) is a medium sized easel painting, but to my eyes, it possesses monumentality and grandeur more usually associated with the types of structures described above. It made a such an impression on my 13-year-old self that that first moment of encounter has become the benchmark for all my subsequent art engagements. I was hooked and I guess, in simple terms, I’ve been looking to replicate that first ‘hit’ ever since.

I’m writing this piece a few days after attending the launch of Dr Peter Simpson’s new McCahon opus There is Only One Direction Vol 1, 1919–1959. In the introduction Peter records his entry point into McCahon’s work as being through his use of text and his relationship with poets such as John Caselberg and James K. Baxter. In describing his lifelong fascination with McCahon he quotes from a 1929 T.S. Eliot essay to make an analogy, ‘genuine poetry can communicate before it is understood.’

This was surely the case for a 13-year-old schoolboy stumbling onto Here I give thanks to Mondrian for the first time. From that moment ‘Mondrian’ and I have grown up together. McCahon painted this work in 1961 and I was born in ‘63. We were both teens when we met and are weathering middle age together now.

On that first meeting I had had very few art experiences and possessed few diagnostic tools with which to deduce meaning. I hadn’t heard of or seen the work of Mondrian but you can bet I did shortly thereafter. But this painting was and remains hugely instructive to me. I’m not sure if we are first drawn to art in search of meaning. But I’ll go to my grave quite sure that we look to art for feeling.

I can’t really recall how I felt when I first saw the work, so I have to recount my response now. The kicker is that I suspect after forty-something years I still experience the same emotions. The startling contrast between those shiny, creamy portions, the ever so slightly irregular angular block of black, and the ‘lip’ of mustard which allows for a grey sleeve of shadow to animate the composition, creating a sensuous, sliding visual game. The counterpoint with McCahon’s wobbly handscript dedication makes for a momentary pause and tension as I ask ‘how and why?’

As I’ve grown older, for good or for ill, I need a bit of understanding to go with those emotions. A writer’s job is to soberly decode and then make a case for an artwork, not gush all over the shop about how amazing it might be, even if it is. Such an approach, also for good or for ill, favours the extraction of cause and effect, of meaning over that swooning sensation that indicates you might be in the presence of greatness.

Over the last few weeks I’ve been a regular visitor to the Auckland Art Gallery and the centenary exhibition A Place to Paint within which Here I give thanks to Mondrian currently hangs. As is the way with contemporary art presentation there are a few helpful hints and quotes accompanying the works to assist the modern observer in reaching their own conclusions. Much is made of McCahon’s GREAT themes (Trump style caps are the writer’s). McCahon’s faith, too much or too little depending on the moment, the landscape and his growing environmental concerns are all on show. But Here I give thanks to Mondrian sits outside McCahon’s customary sturm and drang. The artist is not hunting his usual big game.

At face value it is a simple acknowledgement from one artist to another. And whilst this makes it unusual within McCahon’s overall oeuvre and all the more intriguing as a consequence, its sentiment is not uncommon. Cezanne, Bellini, Milan Mrkusich, Gordon Walters in addition to Mondrian were also the subject of similar homage. McCahon’s act of artistic manaakitanga, his acknowledgement that in his own struggle Mondrian provides a light to guide him, or a measure by which to record his progress, informs this work with a humble gravitas.

In the early 1960s McCahon was, in The Gate series of which ‘Mondrian’forms a vital component, grappling with the formal challenges and opportunities of abstraction where meaning must be communicated with sparer means than the texts, narratives and landscapes of earlier and subsequent bodies of work. Here, as McCahon establishes his voice within an exacting discipline, he reaches out to a father figure to lay claim to his own credentials, and perhaps to seek some form of approval in return.

Such thoughts assist me in attempting an explanation for this oil alkyd on hardboard. Context, history and some knowledge of the currents of 20th century art movements do not however, provide me with any insight into the reason why this work spoke to me as a young boy and asked me to treasure the ‘feeling’ of an artwork.

After forty-odd years of looking at a lot more art, and a decent training for that task courtesy of the Art History department of the University of Auckland I’m still going back to the well in search of that sensation. Here I give thanks to Mondrian started me on that journey so I welcome this opportunity to give my thanks in turn to Colin McCahon.

In August and September of 2019 Hamish documented a roadtrip in search of McCahon’s legacy in 2 parts under the title Six Days on the Road with Colin McCahon

Six Days on the Road with Colin McCahon: Part 1

Six Days on the Road with Colin McCahon: Part 2