Are there not twelve hours of daylight

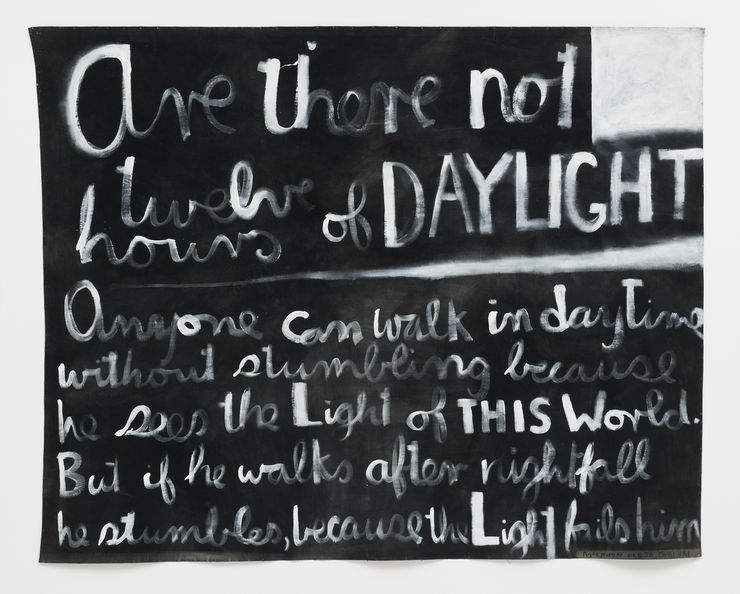

Are there not twelve hours of daylight, Colin McCahon 1970. Synthetic polymer paint, 2077mm x 2580mm. Courtesy of the Chartwell Collection, Auckland Art Gallery Toi O Tāmaki and McCahon Research and Publication Trust.

Published in 2017, Crow's book reconsiders the metaphysical in art through an examination of the work of Colin McCahon alongside Mark Rothko, Robert Smithson, James Turrell and Sister Mary Corita Kent.

Thomas Crow

Art historian, New York

To reflect on the art of Colin McCahon from the Northern Hemisphere is to reverse the terms implicit in responses from the artist’s native New Zealand, perhaps from Australia as well. In the Antipodes, his legacy makes for an inescapable point of reference; even to disregard or downplay him calls for conscious effort. For the very small band of McCahon enthusiasts in the United States, by contrast, even to raise the subject with others invariably meets with blank expressions and bemused indulgence if one tries to conjure a case for him out of the air. Barely anyone has even had a chance to see the work.

The disparity makes something of a mockery of present-day pretensions to global awareness of art. I cannot help wishing it were otherwise (and there is a nascent effort underway finally to bring some signature McCahons to New York), but at the same time I wonder if his absence from the international rankings of art historians is really so significant that it should deeply trouble anyone on either side of the equator? Might it not be as well that some enigmas and secrets remain in the face of a borderless art regime where all are leveled to commensurable tokens in the marketplace of reputations? It has not been so long since lengthy pilgrimages were required to attain any vivid sense of what many great works of art actually looked like. I can attest that seeking and finding McCahon’s work forms part of the total affect that embeds it in memory and consciousness. For an outsider, it cannot be had casually or merely for the asking.

I do not know anyone who has made that effort and failed to be struck with a certain force of revelation, a sense of unexpected illumination of a piece with the dominant theme in McCahon’s later work. Theme is perhaps too weak a word; one might better say the condition of its coming to exist, as Rex Butler and Laurence Simmons have articulated more eloquently than I can hope to do here. But it is with that effect in mind that I propose as its most compelling distillation the 1970 canvas, 'Are there not twelve hours of daylight'.

That utterance of Christ, taken from the eleventh chapter of the gospel of John, begins the saviour’s rejoinder when some disciples speak up against recrossing the Jordan at the pleas of Mary and Martha to save their brother Lazarus. But we were stoned there, they object, and urge Jesus to save himself —a benign but nonetheless ominous anticipation of the later taunts that he come down from the cross or summon Elijah in his hour of need. He replies, with portentous indirection: “Are there not twelve hours of daylight? Anyone can walk in daytime without stumbling because he sees the light of this world. But if walks after nightfall he stumbles, because the light fails him.”

These same words appear in the complete transcription of the tale in McCahon’s epoch-making 'Practical religion', its subtitle, The Resurrection of Lazarus Showing Mount Martha—a “monster,” he called it—begun at Muriwai in 1969. It is difficult not to read those particular lines in relation to the practicality that attended his new conditions of work. A lifetime of day jobs, “farming, factories, gardening, teaching, the years at the Auckland City Art Gallery,” had left him still uncertain as to whether his painting constituted a legitimate occupation to be conducted in daylight hours. So he worked at night: “…as the light fades, tonal relationships become terrifyingly clear,” he wrote in 1972, “At night I paint under a very large incandescent light bulb.”

But those physical circumstances of manufacture readily transposed themselves to the metaphysical. To quote Rex and Laurence, “what he attempts to present to us is … that which precedes the visible and meaningful image, the space in which the image can come to be. It is what we might call light itself, and we identify with it not because of what it means and resembles but in its own right.” The “tonal relationships,” the stark, white-on-black technique seem always to imply a fundamental act of creation: the white interrupting and articulating what would otherwise be a void, harking back to the division of light from darkness in Genesis, the words appearing in the world as if for the first time. As McCahon loads and exhausts his brush, fluid and adaptable rhythms emerge, a swelling and fading of the white pigment's opacity, as the voice itself appears fitfully to grow and wane in strength. Above DAYLIGHT, the most emphatic word in the array, a recessed window of nearly pure illumination holds the upper right corner, while a penetrating incursion of light into the world underscores it, strong where it enters at the right but swallowed in darkness as its force exhausts itself towards the left.

For that light to enter into the spectator’s own meditations, it was vital that McCahon’s own doctrinal allegiance remain undefined. Much ink has been devoted to the problem of McCahon’s personal Christian faith or belief, even though an unambiguous answer, whether affirmative or negative, would only serve to undermine the art. The negative would reduce scriptural content to cool ventriloquism; while the affirmative would allow non-believers, a majority among his actual audience, to dismiss the challenges to vanity and self-regard seemingly couched in the cant of sectarian evangelism. This requirement of his art (where McCahon always started) raises itself to the higher principle of the deity’s radical unknowability and thus scepticism toward all self-congratulatory claims to “believe.”

In occupying such a position, McCahon enjoyed good company. By declaring himself no Christian, he echoed the philosopher and (let us not forget) lay preacher Søren Kierkegaard, whom he likewise paralleled in his fixation on scriptural teaching. Out of the entire New Testament, Kierkegaard favoured the Letter of James, a book of only a few pages to which the New English Bible gives the heading “Practical Religion,” denoting charitable humility and its corollary: excoriation of grasping hypocrites who most loudly profess their faith. A late sermon, “The Changelessness of God,” called out the established church over its worldly venalities, taking as its text a verse from James that might define McCahon’s chiaroscuro of divine light: "All good giving, every perfect gift, comes from above, from the Father of the lights of heaven. With him there is no variation, no play of passing shadows.” In this world, dispiritingly, the lights gutter like a windblown candle.

Not long after I first saw 'Are there not twelve hours of daylight' in the Stedelijk-organized retrospective of 2003, my mother died. She had been living on her own in Santa Fe, New Mexico. The Department of Veterans Affairs saw to the cremation and burial, but it fell to me to improvise a graveside ceremony for the small circle of friends she had acquired there. I chose this same passage from John as the most apposite textual accompaniment to the passage from physical life to its absence: I genuinely could think of no other. Unfamiliar and unexpected, the Elizabethan cadences of the passage struck these listeners as appropriate, or so I think, even as its harsher notes and unconsoling ambiguity hung in the air. For that consoling memory I am indebted to Colin McCahon.

The disparity makes something of a mockery of present-day pretensions to global awareness of art. I cannot help wishing it were otherwise (and there is a nascent effort underway finally to bring some signature McCahons to New York), but at the same time I wonder if his absence from the international rankings of art historians is really so significant that it should deeply trouble anyone on either side of the equator? Might it not be as well that some enigmas and secrets remain in the face of a borderless art regime where all are leveled to commensurable tokens in the marketplace of reputations? It has not been so long since lengthy pilgrimages were required to attain any vivid sense of what many great works of art actually looked like. I can attest that seeking and finding McCahon’s work forms part of the total affect that embeds it in memory and consciousness. For an outsider, it cannot be had casually or merely for the asking.

I do not know anyone who has made that effort and failed to be struck with a certain force of revelation, a sense of unexpected illumination of a piece with the dominant theme in McCahon’s later work. Theme is perhaps too weak a word; one might better say the condition of its coming to exist, as Rex Butler and Laurence Simmons have articulated more eloquently than I can hope to do here. But it is with that effect in mind that I propose as its most compelling distillation the 1970 canvas, 'Are there not twelve hours of daylight'.

That utterance of Christ, taken from the eleventh chapter of the gospel of John, begins the saviour’s rejoinder when some disciples speak up against recrossing the Jordan at the pleas of Mary and Martha to save their brother Lazarus. But we were stoned there, they object, and urge Jesus to save himself —a benign but nonetheless ominous anticipation of the later taunts that he come down from the cross or summon Elijah in his hour of need. He replies, with portentous indirection: “Are there not twelve hours of daylight? Anyone can walk in daytime without stumbling because he sees the light of this world. But if walks after nightfall he stumbles, because the light fails him.”

These same words appear in the complete transcription of the tale in McCahon’s epoch-making 'Practical religion', its subtitle, The Resurrection of Lazarus Showing Mount Martha—a “monster,” he called it—begun at Muriwai in 1969. It is difficult not to read those particular lines in relation to the practicality that attended his new conditions of work. A lifetime of day jobs, “farming, factories, gardening, teaching, the years at the Auckland City Art Gallery,” had left him still uncertain as to whether his painting constituted a legitimate occupation to be conducted in daylight hours. So he worked at night: “…as the light fades, tonal relationships become terrifyingly clear,” he wrote in 1972, “At night I paint under a very large incandescent light bulb.”

But those physical circumstances of manufacture readily transposed themselves to the metaphysical. To quote Rex and Laurence, “what he attempts to present to us is … that which precedes the visible and meaningful image, the space in which the image can come to be. It is what we might call light itself, and we identify with it not because of what it means and resembles but in its own right.” The “tonal relationships,” the stark, white-on-black technique seem always to imply a fundamental act of creation: the white interrupting and articulating what would otherwise be a void, harking back to the division of light from darkness in Genesis, the words appearing in the world as if for the first time. As McCahon loads and exhausts his brush, fluid and adaptable rhythms emerge, a swelling and fading of the white pigment's opacity, as the voice itself appears fitfully to grow and wane in strength. Above DAYLIGHT, the most emphatic word in the array, a recessed window of nearly pure illumination holds the upper right corner, while a penetrating incursion of light into the world underscores it, strong where it enters at the right but swallowed in darkness as its force exhausts itself towards the left.

For that light to enter into the spectator’s own meditations, it was vital that McCahon’s own doctrinal allegiance remain undefined. Much ink has been devoted to the problem of McCahon’s personal Christian faith or belief, even though an unambiguous answer, whether affirmative or negative, would only serve to undermine the art. The negative would reduce scriptural content to cool ventriloquism; while the affirmative would allow non-believers, a majority among his actual audience, to dismiss the challenges to vanity and self-regard seemingly couched in the cant of sectarian evangelism. This requirement of his art (where McCahon always started) raises itself to the higher principle of the deity’s radical unknowability and thus scepticism toward all self-congratulatory claims to “believe.”

In occupying such a position, McCahon enjoyed good company. By declaring himself no Christian, he echoed the philosopher and (let us not forget) lay preacher Søren Kierkegaard, whom he likewise paralleled in his fixation on scriptural teaching. Out of the entire New Testament, Kierkegaard favoured the Letter of James, a book of only a few pages to which the New English Bible gives the heading “Practical Religion,” denoting charitable humility and its corollary: excoriation of grasping hypocrites who most loudly profess their faith. A late sermon, “The Changelessness of God,” called out the established church over its worldly venalities, taking as its text a verse from James that might define McCahon’s chiaroscuro of divine light: "All good giving, every perfect gift, comes from above, from the Father of the lights of heaven. With him there is no variation, no play of passing shadows.” In this world, dispiritingly, the lights gutter like a windblown candle.

Not long after I first saw 'Are there not twelve hours of daylight' in the Stedelijk-organized retrospective of 2003, my mother died. She had been living on her own in Santa Fe, New Mexico. The Department of Veterans Affairs saw to the cremation and burial, but it fell to me to improvise a graveside ceremony for the small circle of friends she had acquired there. I chose this same passage from John as the most apposite textual accompaniment to the passage from physical life to its absence: I genuinely could think of no other. Unfamiliar and unexpected, the Elizabethan cadences of the passage struck these listeners as appropriate, or so I think, even as its harsher notes and unconsoling ambiguity hung in the air. For that consoling memory I am indebted to Colin McCahon.