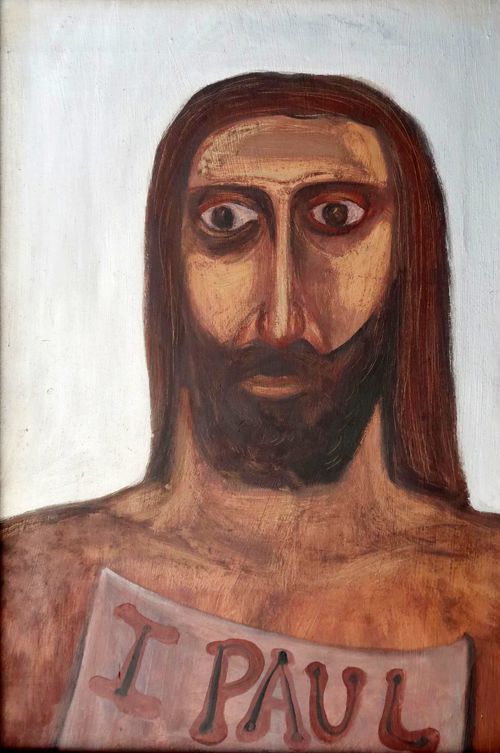

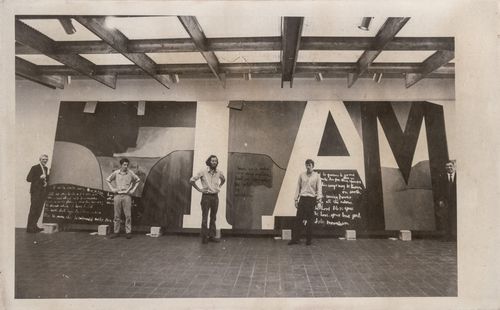

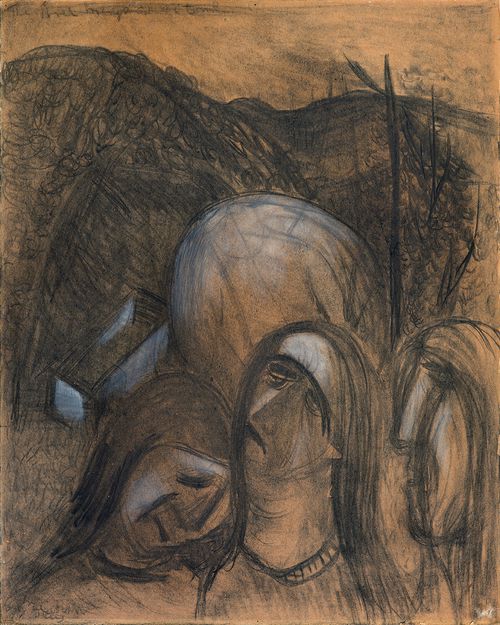

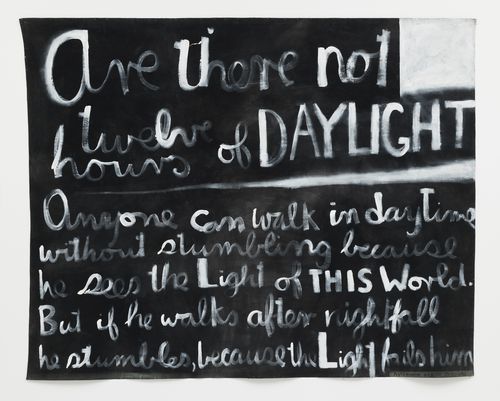

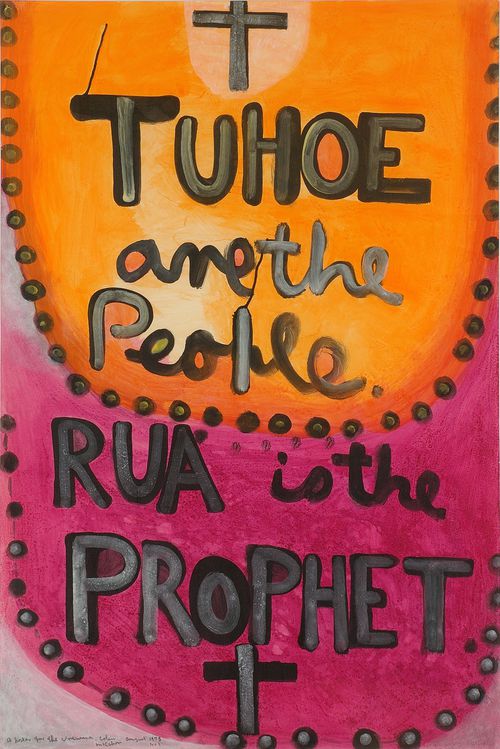

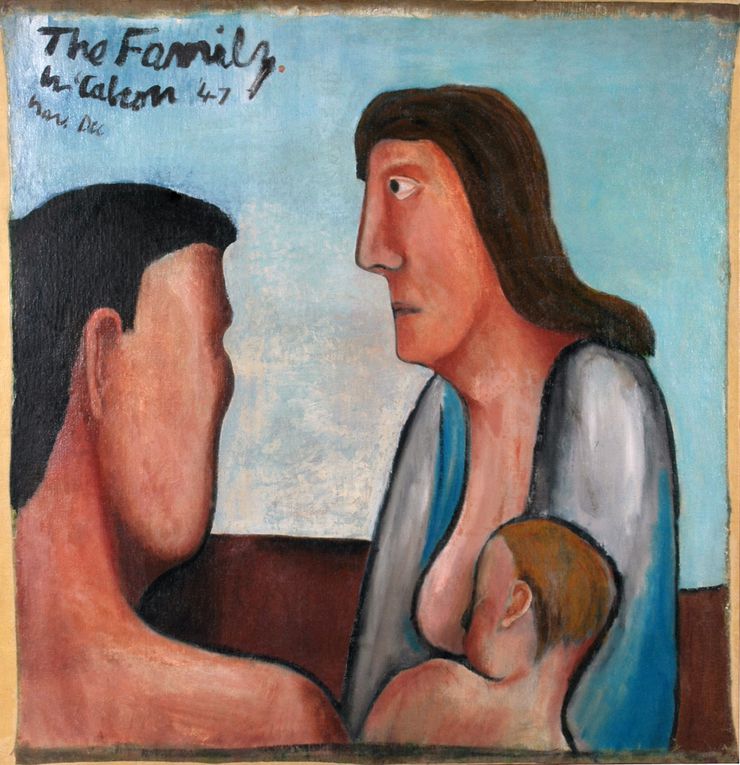

The Family

The Family, 1947, oil on canvas, 930 x 898 mm. Private collection. Courtesy McCahon Research and Publication Trust.

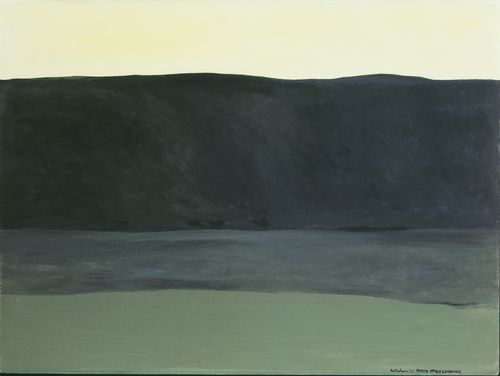

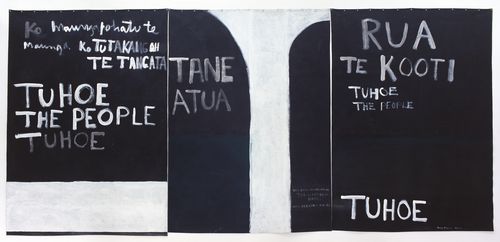

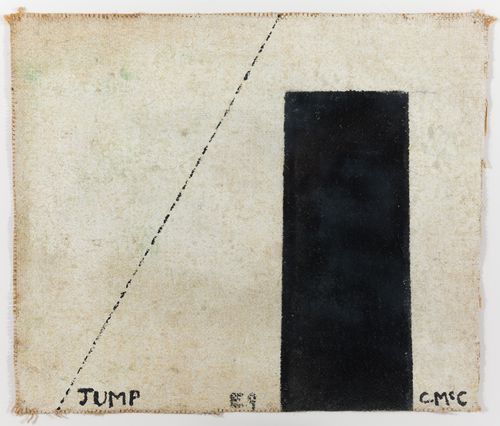

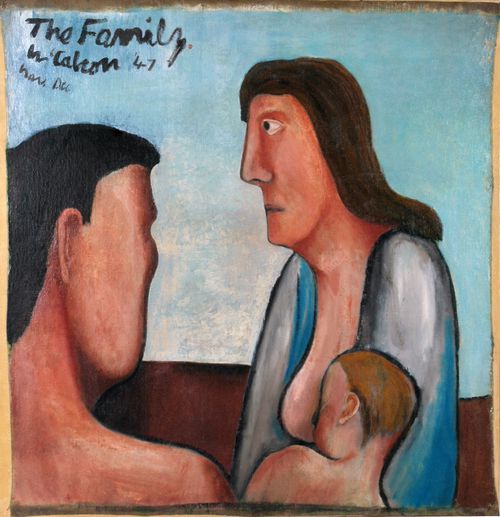

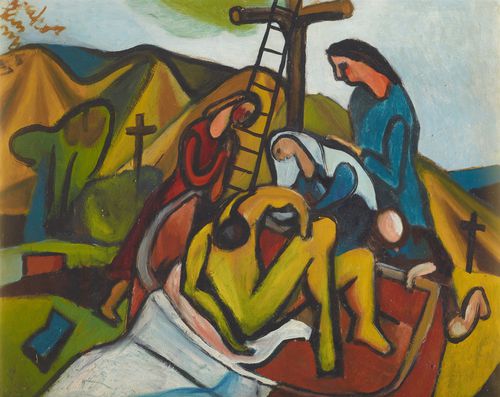

Brent Harris, Study #2 for more ,2019 oil on linen , 705 x 520 mm. Private collection

Brent Harris

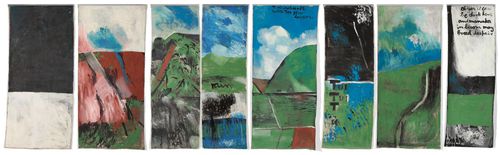

I first saw McCahon’s painting The Family (1947) in 1975, when it was included in the exhibition McCahon ‘Religious’ Works 1946-1952, a touring exhibition that started firstly at the Manawatu Art Gallery, Palmerston North, my hometown. Curated by Luit Bieringa, the Manawatu’s director at the time, this highly significant exhibition of Colin McCahon images drawn from Biblical scripture would visit seven subsequent institutions.

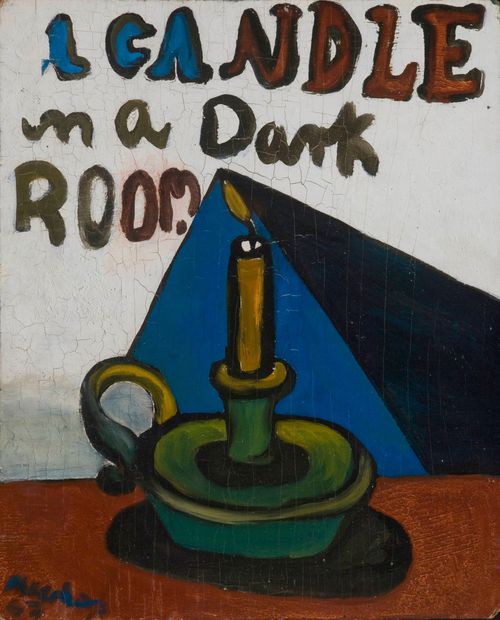

Though the presentation surveyed a wide range of imagery, this particular painting of the holy family spoke most directly to me. Much more than just a generic religious depiction, it seemed to carry a heavy and more universal psychological weight, for this is not at all a happy looking family! Mary, the only one of the three whose face we can read, is grim, as if she can foresee the future fate of her child. And the male figure at left – Joseph apparently – his gaze averted from us, takes on an ambiguous character. I was then and continue to be struck by the thought that this image might have more specific autobiographic significance - are we in fact looking at the artist’s family? Mary a stand-in for McCahon’s wife Anne, Joseph a stand-in for the artist? Either way she’s still looking grim, he inscrutable, the child buried in a nurturing breast.

The exhibition as a whole and this work in particular had a very powerful effect on me. At nineteen years of age in 1975 and struggling with my sexuality, I nevertheless got married this same year. My struggle, part of a rather complex journey through childhood and toward maturation, dominated by an overpowering father, was totally an internal one, and the cumulative paintings in McCahon’s exhibition seemed to speak directly to my own questioning. Identity, doubt, redemption. I immediately felt this man was going through similar struggles as me. A struggle that led to me coming out at the age of twenty-two, leaving the marriage and relocating firstly to Auckland in 1978 and then to art school in Melbourne from 1981.

As I grew older and started to study McCahon's work more, to read his biography, and to see his life’s trajectory, I still connect these original feelings about The Family to McCahon the man. I never felt that his endless search for redemption was a searching to save you or me, but rather to save himself. One would have to say on a personal level he didn’t win. And though I have always felt McCahon a deeply psychological artist, most of the writing on McCahon covers his relationship to religion, his relationship to the country, his tough reception as an artist in New Zealand. Projecting my own situation perhaps, I have always felt there was something deeply eating away at him, from the inside.

It is curious to me that most of the writers on McCahon are heterosexual male. I have enjoyed the two most recent additions by Justin Paton and Peter Simpson, soon to be followed by Wystan Curnow. As well Laurence Simmons and Rex Butler have an upcoming publication, but I do long for a biography of him written by a New Zealand woman. I wonder if we might find a different McCahon there?

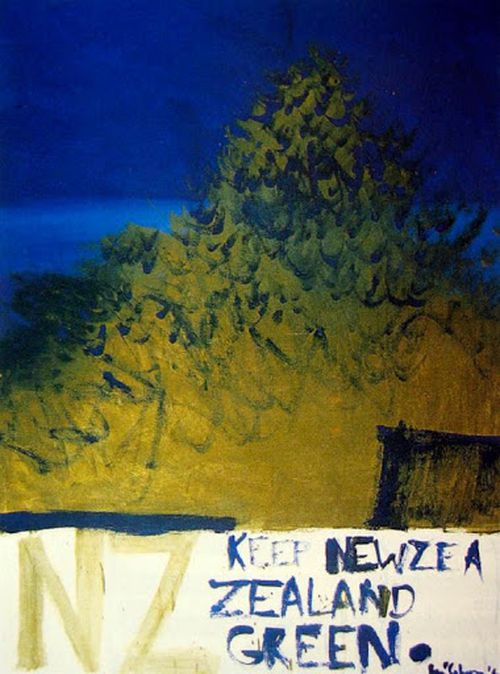

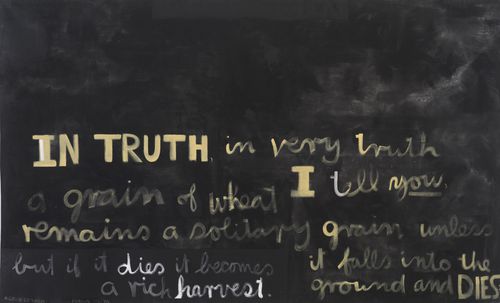

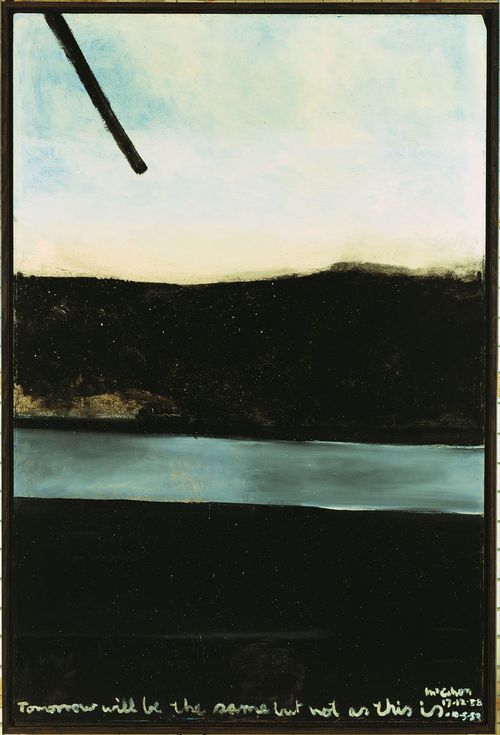

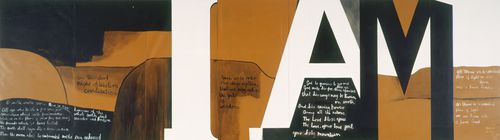

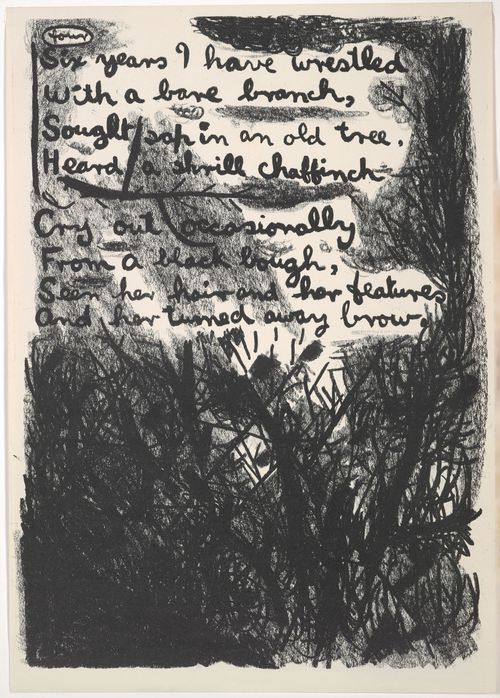

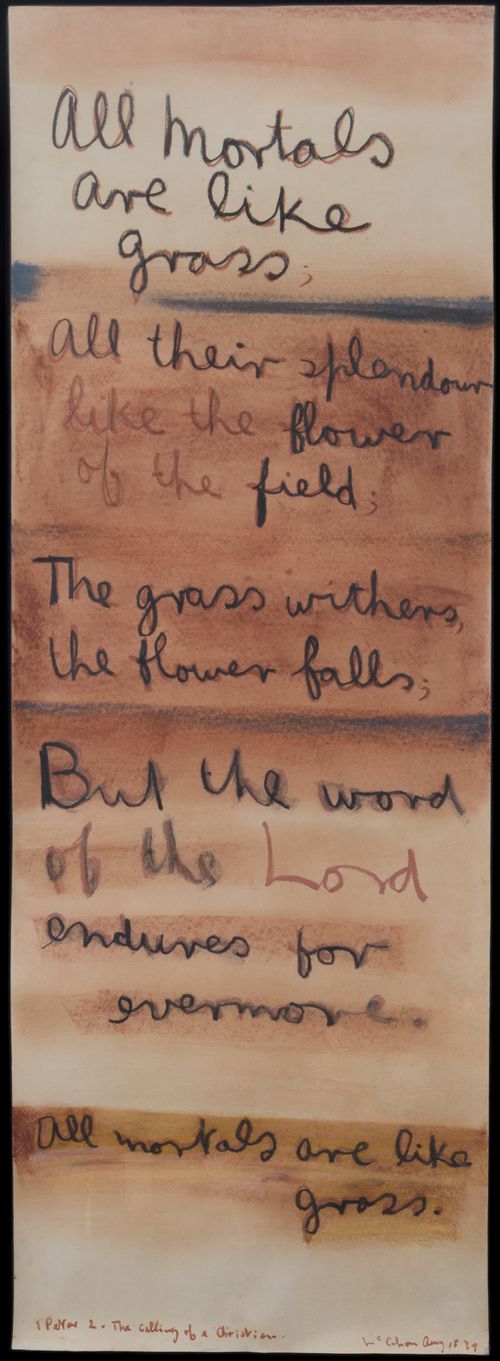

I still ask what was driving his inner struggle, this question for me most emblematic in his painting The Family - a question that keeps my psychological interest in his work. That this painting has influenced many of my own series is indicative, most obviously in the series of Grotesquerie - 26 paintings made over an eight-year period from 2000 to 2009, and depicting figurations from my own family drama. And the painting, Study #2 for more (below) from 2019, as well deals with the family subject – a dominating father, a mute mother, with death (mortality) stalking them both.

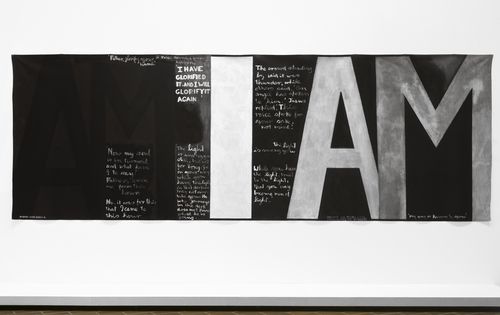

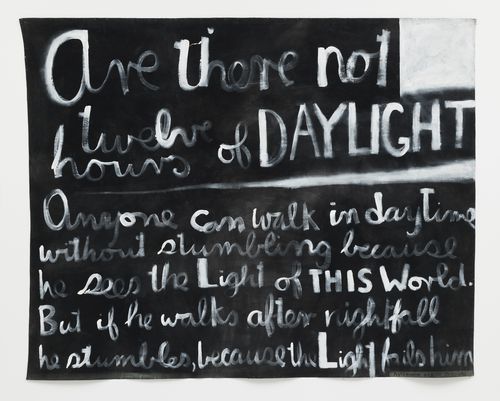

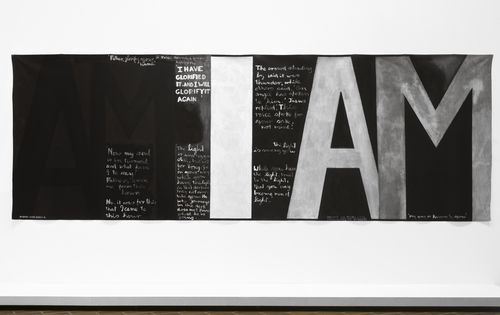

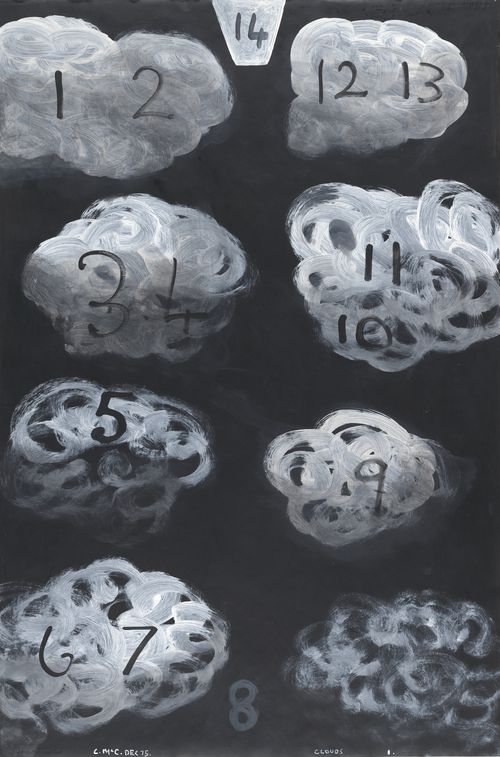

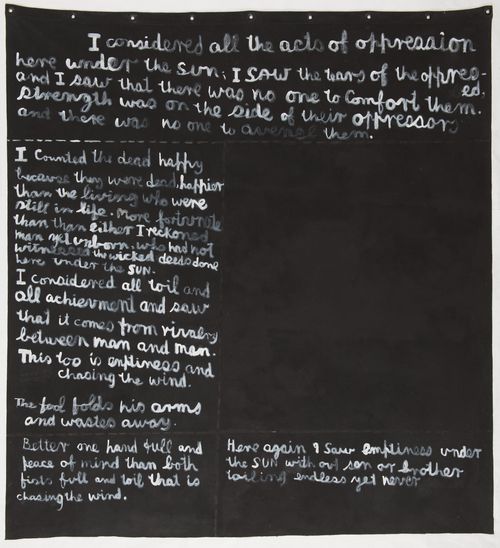

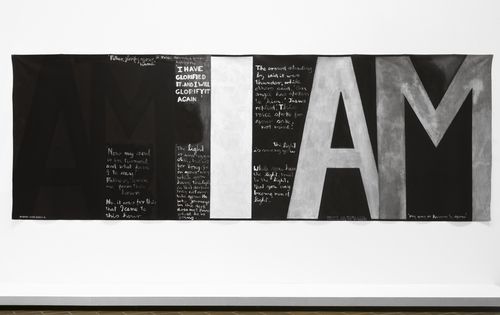

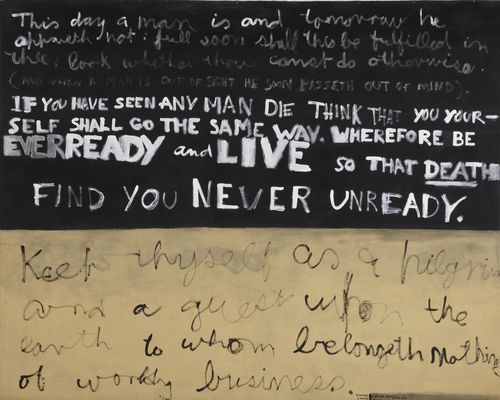

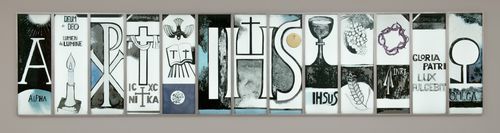

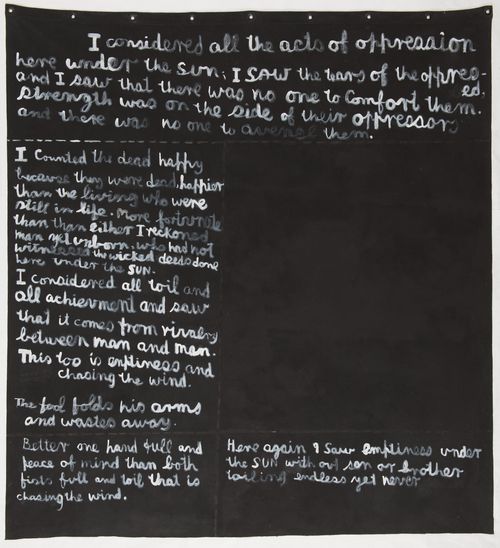

In Sydney in 1984 I saw the exhibition I will need words: Colin McCahon’s Word and Number Paintings (Power Art Gallery, University of Syndey, Australia, 1984). I have always lamented his statement ‘I will need words’ because though I love all of McCahon’s work I do find the late text paintings more and more belligerent, speaking less to me about his doubt and questioning of faith, and more of a repressed anger. The three artists who have influenced my work most profoundly on a psychological level - Louise Bourgeois, Edvard Munch and Colin McCahon - all seem to hold anger in a variety of stages of check.