Muriwai

Muriwai, 1974, synthetic polymer paint on unstretched jute canvas, 937 x 1048 mm. Courtesy of Matthew O'Reilly and McCahon Research and Publication Trust.

Installation for Robin, 2019. Image courtesy of Matthew O'Reilly

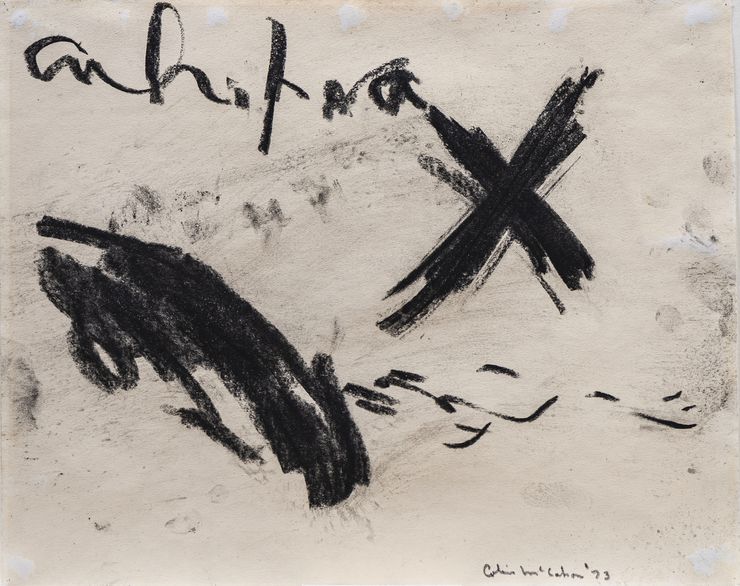

Jet out from Ahipara, 1973, charcoal on paper, 275 x 350 mm. Courtesy of Matthew O'Reilly and McCahon Research and Publication Trust.

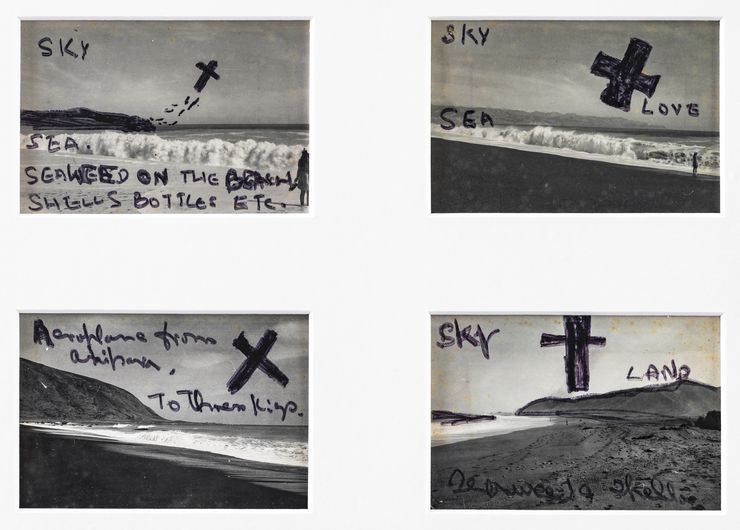

Four matted, collaboratively annotated, photos, 1970-1973. Image courtesy of Matthew O'Reilly

Matthew O'Reilly

I: Presence and Absence: a wound at the heart

1973.

A true loss remains a loss. Our daughter Rebekah’s and my relation to this painting is Robin who fought cancer through all of our time together—something under four years all told. She and I met in 1969 during the last days of regular passenger liners at Cape Town harbour. She did not know of her cancer then, but a week and a bit later she did.

After her death, in the storm of my grief, I asked Colin if he could help me remember her; he replied that he would know it when he saw it and that he intended it for both Rebekah and me. In about one further year’s time he did: its brush point date anchoring it in a larger reality.

My memories have painterly qualities.

Such can be the tricks of the distressed mind: I have lived this story as a protective fiction, partly for want of many clear (photographically detailed) memories. This purely physical artefact [and I am pointing at it, now] in many ways constitutes my hold on a reality that I constantly question—back and forth between a real world, long past and ethereal, and my uncompetitive wounded (blunted) imagination.

This painting fills a need for a perceptual continuum between the internal wound and a once material reality; the material evidence is at once deeply absorbent of all light in the ocean of forgetfulness, while in an ongoing mystery, in the drenched air above, light is in the process of breaking through—time is passing—tonally precise. This painter’s capacity to make light operate like this, actually with such photographic precision, was always his. I belonged to a household for which this property was a given from my earliest childhood. You may recognise this relational quality in his works, whether as a blessing or not.

II: Structures of support: survival

In the storm of my father, Ron O’Reilly’s grief (and I saw it distinctly) he too reached immediately out to his old friend, Colin McCahon, sending him four small 3 x 4 1/2 inch photos of big landscapes taken on the southern coasts of the North Island that Robin looks small in, as if to illustrate his own relation to his daughter-in-law and her journey, and the shock of her departure. In a few days the photos returned, marking the losses of Colin’s own life in the recent past to add to those of another, remarking in felt tip pen also the detritus to be seen in the images. Robin was not related by blood or by fame, but Colin treated her as if she was both.

Colin was not a distant figure. Colin is not a distant figure.

He could make symbols out of (the formal attributes of) aeroplanes. Ron sent me one. About two weeks after Robin succumbed, during an early-arriving Easter, Colin poured out a large number of charcoal drawings that worked through the ara, the journey, of departing spirits. Among these images he clearly wrestled with the dissolving differences between the solid realities of corporeal substance, of aeroplanes, of wooden (charcoal, carbon) crosses, which together in the mind begin to resemble the fluid currents of sea (water) and air.

Colin had lost at least Baxter and his own mother, Ethel, from his recent life and now another—Robin. (Brasch too was to go in a month or so.) Each loss would generate responses.

The charcoal series is collectively known as Jet out (1973). Robin, a Sydneysider, had fled her country (I too had fled mine) to various parts of the world. In her story she wanted to put her roots down in Aotearoa New Zealand, but multiple times over the three plus years she was forced by her illness (and hope) to leave. Now by aeroplane.

Colin knew this story. I do not know what went on in his creative mind during the making of these charcoals but I want to believe her reluctant journey(s) home to Sydney were at play somewhere in his mind, becoming embedded in the symbolism within the body of works. Who knows? At least, the echoes of that thought continue to give me warmth. I hope it went something like that.

III: The later frames of Colin McCahon

A possible reason to come here.

I do know that a greater number of people of Colin’s generation who grew up in the aftermath of the first world war, were more deeply rooted in Christian and 19th century thought and reactions to it—including various strands of socialist activism—than we can easily know today; a sense of communal obligation was more deeply bound in their culture than in mine. Certainly, my later generation than his and my father’s was already at a greater distance from the deeper history that could provide us today with clues to understanding the artist’s culture and art.

An ecology of community.

The set of annotated photos (collaborative artwork?) coupled with an explanatory text by Ron was to perform a didactic function in his Govett-Brewster touring McCahon exhibition entitled Necessary Protection in order to illustrate the artist’s deeply personal relation to his subject matter—the communality of his art, towards whom he aimed his work(s); a parallel relation you could say as the related works (series of works) that came under the ‘necessary protection’ rubric bore specific reference to our mounting ecological anxiety.

Framing and its sublimation.

Within his endeavour, sometime after his arrival in Auckland, I believe that the painter began actively to search for ever more formally direct ways to bind the affective relation of the painted artefact to its content and thence to the viewer. Because humanity itself was so fiercely his subject, all of us his subject (with a dawning consciousness of the ecological hazards being created), the idea of vulnerability became bound inexorably to it. In this regard, with big help along the way from his American trip, he began to steer steadily towards a point of framelessness (nakedness) in his paintings—witness The Wake (1958) and The Northland panels (1958). Manifest framelessness became part of the power of the artist’s message. It is my contention that while it seems clear the precarious nature of his media and its lack of framing (the exposure at its edge to the dangers of thoughtlessness) is intended, importantly it was an explicit expression of its affective content (or aspects of it), and further, another means to direct the message and its energy, unmediated, straight at his (its) viewer’s mind and heart.

Simultaneously to remind and to sooth:

When Muriwai (1974) was used in Victoria University of Wellington’s Adam Gallery exhibition Behind Closed Doors in 2011 it was placed centrally at the end of the long axis of the top floor. (The architect makes one come around a corner to be surprised by the dramatic space.) The concentrated singularity of the art piece was transfixing at that distance. The view through the full length (say 25 metres) of this very pure space to alight on the painting where it was small to the eye was revelatory: it had a jewel-like precision and was completely legible. The light emanating from the storm cloud communicated a miraculous effect. For this pleasure I didn’t mind its absence too muchi.

It seems to me the deepest of unintended ironies that my small painting, made smaller by the curated perfection of its setting, could so command attention, and yet be there only really because of the sale of Storm warning. Same motif, different motive.

Constant exposure in this case is indispensable to my maturation. Because of ongoing exposure to this painting (paint and canvas) I have been given access to a far deeper history than I might otherwise have perceived. Every day, as I walk past it, I am a thankful participant at an art function, catching up on our mutual progress, arguing, laughing, crying. This painting is not Robin but a theatre telling of an instance of human drama relating to her and Rebekah and me, evidence of its dimensions. Like so much that McCahon did, that good art can do, it is transcendent, its interior light pulsing at me.

Somehow, I suppose I have more need of it than it does of me, personally. And then, there’s always another generation. As Ron said: “There’s nothing like living with art…”

//

Newly retired, for nearly 34 years I was the framer of paintings first at the National Art Gallery and then Te Papa Tongarewa. I was exposed from the very beginning (1945) to Colin McCahon’s paintings in the house of my father R.N. (Ron) O’Reilly. Through this continuity I became aware of the artist’s evolution towards an art and its materials that could avoid framing.

I want to acknowledge Luit Bieringa for giving me an opportunity to engage with the power of the frame through its presence or absence. Little did the institution(s) know what they were getting into. Lots of stories there, thanks Luit.

[i] My great thanks to Christina Barton’s conception and Laura Preston’s curation of this very smart show for the mind-expanding placement of Muriwai, 1974 - in its play between size and scale – and to the memory of architect Ian Athfield for providing the setting to allow it to happen.