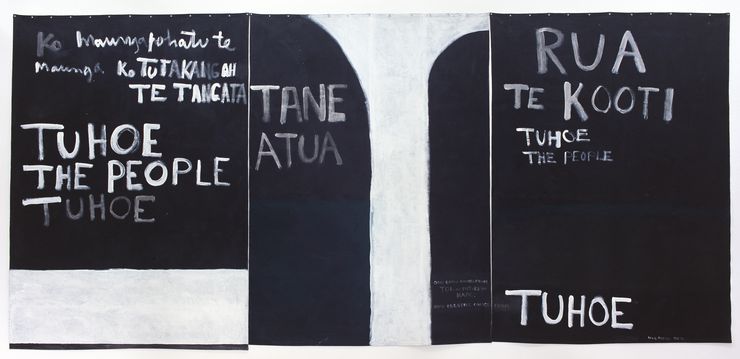

Urewera Triptych

Urewera triptych, 1975, synthetic paint on unstretched canvas, 1: 2520 x 1793 mm, 2: 2475 x 1798 mm, 3: 2450 x 1780 mm. Private collection. Courtesy McCahon Research and Publication Trust

Installation view Te Mihaia Hou: Maungapōhatu and the prophet Rua Kēnana Contemporary art about the prophet Rua and the Millennium at Te Whare Taonga o Waikato Waikato Museum of Art and History 15 February – 1 May 1991

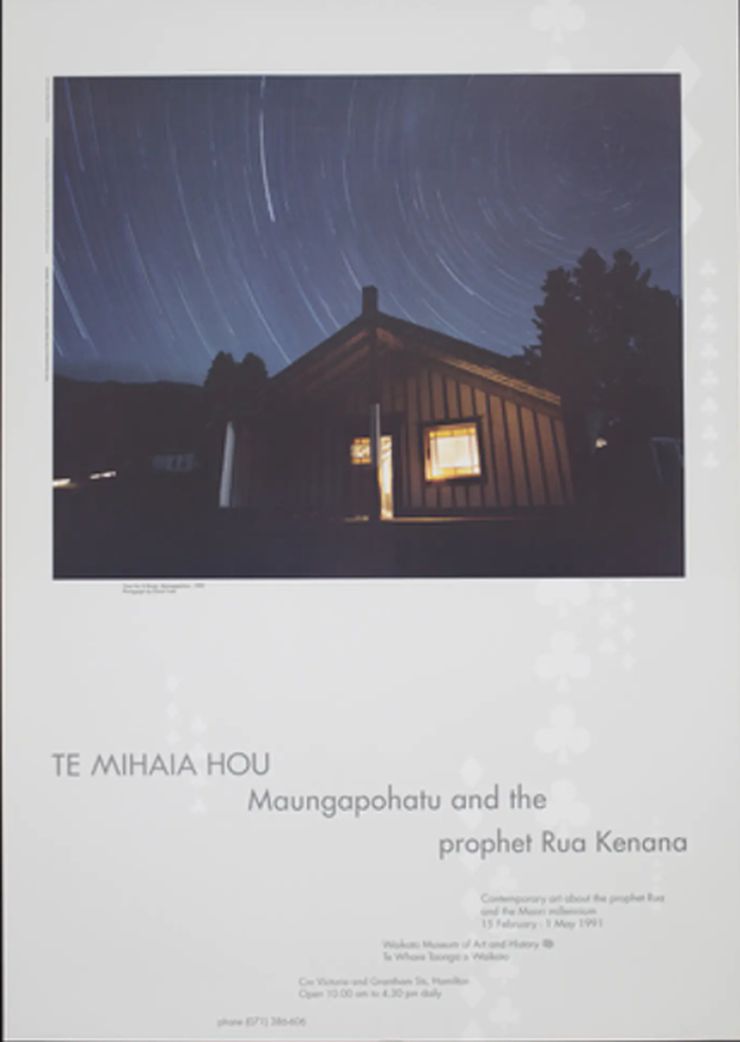

Catalogue cover Te Mihaia Hou: Maungapōhatu and the prophet Rua Kēnana Contemporary art about the prophet Rua and the Millennium at Te Whare Taonga o Waikato Waikato Museum of Art and History 15 February – 1 May 1991

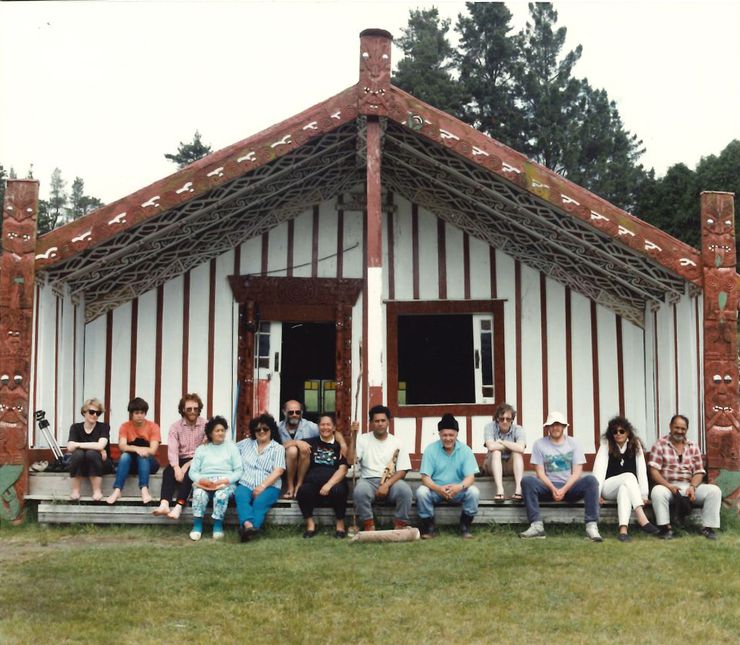

Outside Tane-Nui-A-Rangi at Maungapōhatu 10 November 1990. Hirini Melbourne and Wharehuia Milroy (centre), author seated far left

Poster for the exhibition Te Mihaia Hou Maungapohatu and the prophet Rua Kenana at the Waikato Museum of Art and History. Image Tane Nui a Rangi at Night by David Cook

Linda Tyler

My favourite part of making exhibitions is getting to move artworks around and see how they look in relation to each other in the gallery. Larger institutions have everything locked down months ahead of opening, but I am lucky to have always worked for smaller places where you are the one lifting off the Tyvek as the painting comes off the roller. It’s a great privilege to get to see the back of paintings, to feel their heft and texture, while manoeuvering to get them on the wall. Although it seems banal to say so, art works can be very powerful. This one, and its sister painting, the Urewera Mural (1975), do seem to have created ripples.

Even though it is 28 years ago, I can remember the exact spot in the Level 5 gallery at the Waikato Museum that we hung Colin McCahon’s Urewera triptych for the exhibition Te Mihaia Hou: Maungapōhatu and the prophet Rua Kēnana in 1991. McCahon himself had died only four years previously, and the work itself was just sixteen years old, but already he seemed like the Old Master of New Zealand painting. His smoky breath still clung to

this work, giving it the aura of a great masterpiece.

We made it the hero of the back wall, the artwork that pulled you into the exhibition with its command of the space, visible from the bottom of the stairs before you even entered the gallery. It had some competition for visual dominance with a one-third scale model of Rua’s council house Hiona in the centre of the room.

Although it is not as notorious as the Urewera mural (for which it was ‘A Painted Drawing’), I find the Urewera triptych the easier work to conjure in my memory. For me, McCahon is acting as a translator, conveying his understanding of how Māori had been wronged in the Urewera to a Pākēha art world, in preparation for making his final painting. Presumptuous, perhaps even wrong-headed, but well-intentioned, and full of feeling.

Recently the work has travelled to Hong Kong, where it may have been ‘read’ from right to left. When I looked at the image on the McCahon website, I realized the two panels had been transposed in collaging together the image. The duplicity of the digital world!

We have McCahon’s own words to tell us which way round the panels go. Writing in 1974 to his friend Ron O’Reilly, (who was about to become the third Director of the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery), McCahon described what he was trying to do with

the work, which had been commissioned by the Urewera National Park Board:

I’m painting on black so I can do the romantic thing in white & bring “the one without a name” into the picture … I think it’s Tane-Atua … But it’s to the God of Trees: he needs some help as the pine trees come in: I feel they belong to a very different religion. So even if I have to start again I now know what it is about … Tane in the middle, the Tuhoe People on the left & Rua & Te Kooti on the right—and the Tuhoe who continue.1

As has been well-documented elsewhere, McCahon got into trouble for choosing Elsdon Best’s informant Tūtangahau as the ancestor in the pepeha, but no one disputes the significance of Maungapōhatu to Tūhoe.

My Tūhoe colleagues at the University of Waikato, Hirini Melbourne (1949–2003) and Wharehuia Milroy (1937–2019), facilitated a trip in May 1990 into the Urewera to moot the idea of an exhibition about Rua. Just two years earlier, Wharehuia had brought the WAI 36 Tūhoe lands claim to the Waitangi Tribunal on behalf of Ngāi Tūhoe. This was eventually settled as part of the Tūhoe Claims Settlement Act 2014. In May 1990, Wharehuia took me in to visit Pei Atawa, the Tūhoe Trust Board Chair at Ruatāhuna, to talk about how the exhibition could help instigate a movement to get Rua Kēnana a statutory pardon.

We made a second trip to stay at Maungapōhatu on 10 November 1990, taking the museum photographer David Cook with us. Hirini Melbourne who was researching taonga puoro at the time, brought many musical instruments along with him, which he played inside the wharenui late into the night, illuminated by a kerosene lamp and a candle. I remember the eerie sound of the pūrerehua as it spun on the end of its cord. David Cook left his camera outside the meeting house for a 4 ½ hour exposure (10.30 p.m to 3.00 a.m.) using a wide-angle lens, capturing the earth’s movement as circular tracks left by the stars and planets. We used this image on the poster for the exhibition because its blue and yellow colours linked to the colours used by Rua’s community, and the circular paths of the stars traced the shape of Hiona as well as suggesting that Rua was attempting to establish an independent axis around which his own community could revolve. It was a cold night, but in the morning it was warm and sunny, and we walked out the ‘six foot track’ from Maungapōhatu towards Tawhana.

Shortly before Christmas in 2019, more than 200 people, including Māori King Tūheitia, assembled to witness the Rua Kēnana Pardon Bill being signed into law at Maungapōhatu marae by Governor-General Dame Patsy Reddy. Rua Kēnana is only the sixth person in New Zealand to receive a statutory pardon, and it was the first time in history that an apology has been signed into law on the original site of the wrongdoing. Not only was this an acknowledgement that he had been unlawfully arrested and imprisoned, causing lasting pain and disadvantage, but it was also a declaration to restore his mana and that of his descendants. 103 years after his arrest, 44 years after McCahon painted the Urewera triptych, and 28 years after the Te Mihaia Hou exhibition, justice had finally been served.

[1] Colin McCahon to Ron O'Reilly, December 1974, qouted in Simpson.

Purchase a print publication of McCahon 100 here.