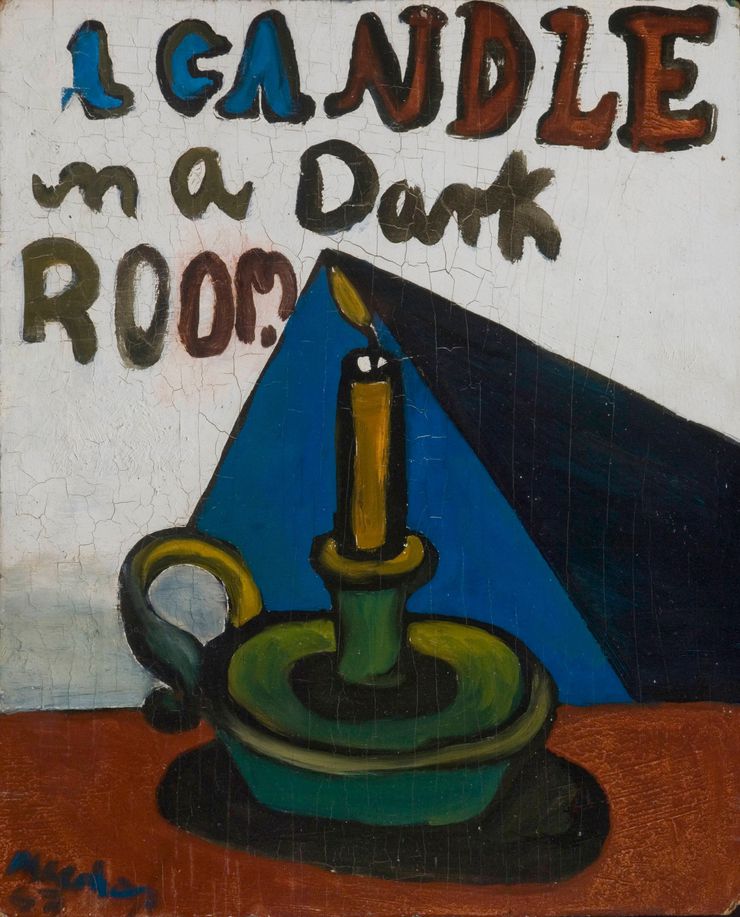

A candle in a dark room

A candle in a dark room, 1947, oil on hardboard, 380 x 310 mm. Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, on loan from private collection, courtesy McCahon Research and Publication Trust

Frances Hodgkins, Pleasure Garden, 1932, watercolour, 875 x 750 mm, gifted to the Christchurch Art Gallery 1951. Image courtesy Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū

W. A. Sutton, Homage to Frances Hodgkins, 1951. Image courtesy of Christchurch City Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū

Mary Kisler

Colin McCahon, as has been noted by many, cast light on the importance of New Zealand art, painting works that speak of our own land, our own turangawaewae, underlining the power of both paint and words to move us beyond the everyday.

Painted the year I was born, and the year Frances Hodgkins died, Candle in a Dark Room (1947) has always had significance for me. Symbolically in both art and literature, the notion of a candle lighting the way; casting light on ignorance; offering hope; illuminating the power of both art and artist to shift us in our perceptions and in our thinking, is ancient.

The cave paintings at Lascaux were made possible because of the blazing torches that illuminated the perennial darkness. In western art, generally, the candle offers hope, but once wisps of smoke signal it is spent, it also warns of the passing of time. It can symbolise the gleaning of knowledge, or draw our attention to human weakness or distress.

McCahon was one of the supporters who played a part in our ongoing understanding of the more radical work of Frances Hodgkins and its reception in Aotearoa. When Hodgkins’ The Pleasure Garden (1932) was rejected by the selection committee for Christchurch Art Gallery in 1948, McCahon was among the vociferous group who rallied in an attempt to push the acquisition through. Even after they raised the sum necessary to acquire the watercolour, (McCahon was only able to donate 10 shillings, whereas Rita Angus contributed the princely sum of 12 guineas,) the work was still rejected, and it was several years before it quietly entered the collection.

It was what the painting represented that was of most concern to local artists and contemporary collectors, who were eager to study and absorb the ‘modern problem’ that had set Europe alight in the late 19th century. At the time, Bill Sutton painted a portrait of leading Hodgkins supporters debating its worth, McCahon leaning on the easel on which the work was displayed. Candle in a Dark Room has closer links formally to some of Hodgkins’ cubist works from the mid-1920s, but it was what The Pleasure Garden symbolised—a break with the past, casting light on the future of art—that held particular resonance with New Zealand’s own modernists.

There is a lushness in the way paint is applied in Candle in a Dark Room, the artist using hardboard rather than traditional canvas as its support. Its structure invokes a simplified cubism: thick black outlines; slightly wonky multi-coloured lettering; the way the flame is made to bend sideways, constrained by the blue triangle behind it. Unlike the muted palette of Braque and Picasso’s cubism, (both artists included the candle motif in their still life paintings), here the dynamic palette is rich and sonorous. The sinuous form of the shadow that underlies the candlestick contrasts with the blackness that stretches back from the tip of the flame, implying perhaps that not all of us avail ourselves of understanding or knowledge when given the chance.

Years later, when McCahon was the Keeper at Auckland Art Gallery, Pleasure Garden was one of the Hodgkins’ watercolours exhibited as part of the group show, Six New Zealand Expatriates. He concluded his introductory catalogue essay; ‘Can any land that has in any way ignored its artists justly claim as its own the refugees it has created?"1 Yet Hodgkins, while basking in her position as a leading British modernist of her day, cared deeply that her work might one day be accepted in the land of her birth. She would relish the attention that her works so rightly attract today. McCahon and Hodgkins share the privilege of now having websites dedicated to their practise, allowing a rich understanding of their individual practice and its relationship to the ongoing story of New Zealand art today.

https://completefranceshodgkins.com/

http://www.mccahon.co.nz/

[1] Margaret Frankel. Year Book of the Arts in New Zealand No. 5, edited and published by Harry H. Tombs, 1949. Also published as ‘From the Archives: The 'Pleasure Garden' Incident at Christchurch By Margaret Frankel’, https://www.pantograph-punch.com/post/pleasure-garden-incident (first accessed 1 June 2017), by Francis McWhannell.