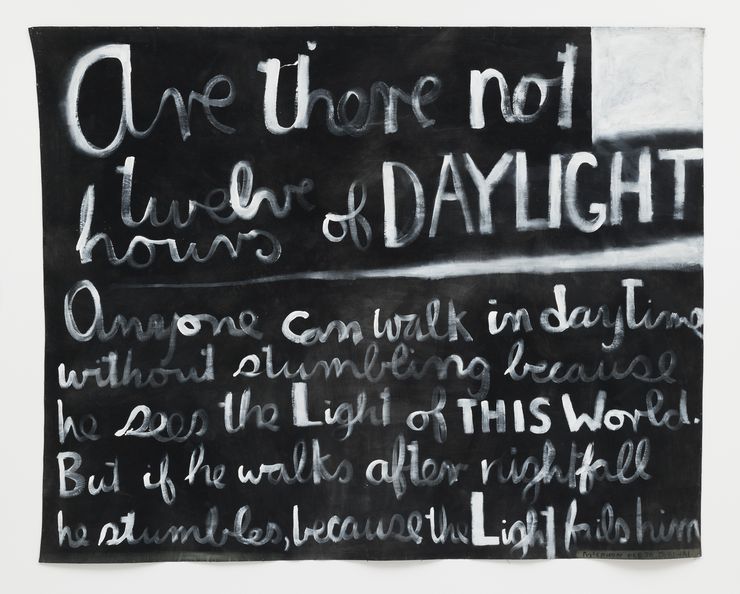

Are there not twelve hours of daylight

Are there not twelve hours of daylight, 1970, synthetic polymer paint, 2077mm x 2580mm. Courtesy of the Chartwell Collection, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki and McCahon Research and Publication Trust.

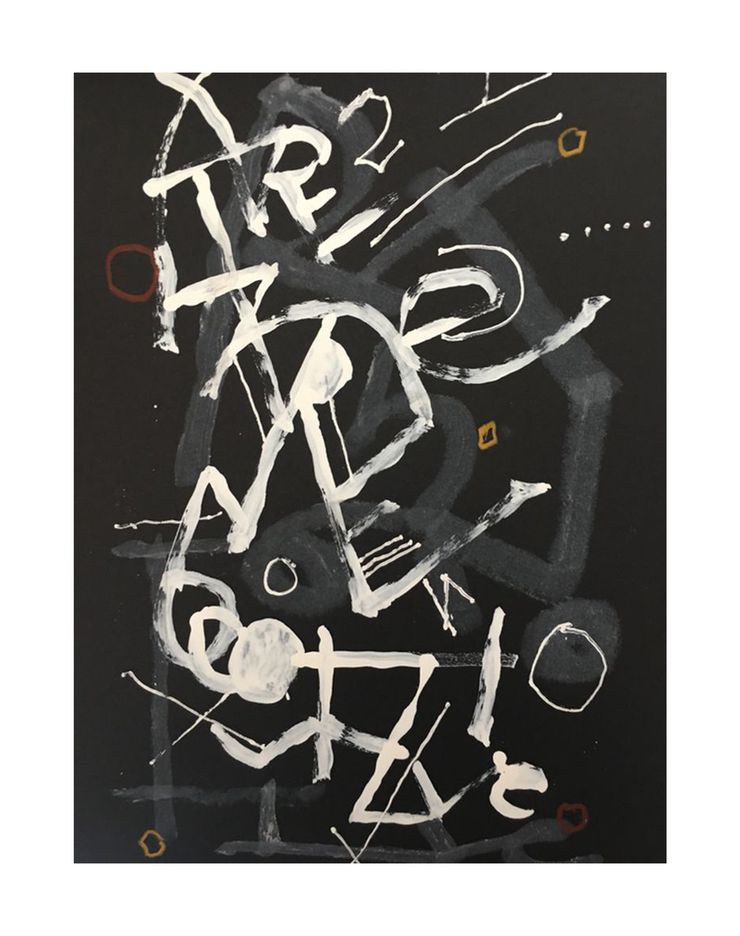

Robert Gardiner, untitled, 2019, acrylic paint and markers on paper

Robert Gardiner

Colin McCahon’s white writing paintings were a revelation to me when I first viewed them at the Auckland Art Gallery, it was in the 1970s I think. They were so testing of one’s engagement with content and means. Given time, and beyond the insistent intellectual meanings of the words, they powerfully delivered the experience of that different kind of ‘meaning’, of concrete poetic expression and composition. With white paint marks on a recessive black ground, it is a work of a kind I have come to value in much art making, including many of the works purchased for the Chartwell Collection. McCahon’s practices thus became influential learning points for me; pulling together artmaking influences from Europe, North America and Eastern sources, and Te Ao Māori.

The use of white on black often reminds me of white chalk on blackboards – a familiar experience for school children, at least of my generation. I would sometimes wonder about the curious aesthetic reversal in the classroom where teacher used white on blackboards and pupils used black on white papers in their books. I guess that before paper was invented children would have used white chalks on black slate. White advances, black recedes – a ‘push pull’ effect which is also at play in McCahon’s writing works.

Historically, the widespread use of hand printing and writing as technical tools recording the meanings of spoken communications, enabled the promulgation of ideas, contributing hugely to cultural development. It prompts reflection on the history of cursive writing, which used to be widely taught in schools and which McCahon would have learned, as I did, along with most schoolchildren of the time; some now don’t, I am told! McCahon used both hand printing and cursive writing in his painting practice and for me, they both provide the experience of prioritising the aesthetics of marking in art over intellectual understandings of literary or religious meanings to be found therein. Does this prompt reflection upon a dichotomy or similarity between religion and art? MMMM maybe. Or is it just my interest in the phenomenon of art making as creative thinking and its relationship to many religious rituals?

The impulse to read words in artworks does help to slow the looking – a device valuable to the deeper aesthetic and formal experiences accessible in works like Are there not twelve hours of Daylight (1970). The use of writing in artmaking by the most outstanding and influential NZ painter in our history seems significant to me, and this beyond any literary or religious content. The quality of his direct and lucid marking, informed by prior familiarity with cursive writing, provides a clue to the innovative impulses involved in artmaking of this kind. Confidence to create empirically shows in such marks and is felt by the perceiver.

McCahon obviously found the inclusion of bible texts valuable to his work. They would have been known to him from repeated readings, providing a way into meditative spiritual/religious interests he obviously had and which provide gravitas to the art work (common to the history of Western religious subject painting). Repeating in mind certain remembered poetic or religious verses helps one enter the meditative and productive state of mind, and remembering them as one actively creates, facilitates a flow of natural and direct mark making prominent in many of McCahon’s paintings.

Deliberate use of a paint-loaded brush as a drawing /calligraphic tool energised by the confidence acquired as one learns the dynamics of cursive writing, moves the mind closer towards a subconscious, intuitive state that is so important to creative thinking in natural marking. Those who have learned cursive writing and the laying out of sentences in lines, can also more readily access the impulse to begin and the intent needed for such marking. By this I refer to calligraphic invention of sequences of marks for their own aesthetic sake.

Familiarity with the impulse to create cursive writing transfers as a similar creative impulse to painting of the kind McCahon practiced. Such direct physical marking engages thinking and acting as a creative process in time. Learning writing also provides compositional experience important to all drawing and painting and would have informed McCahon’s intuitive placement of the words, his marks, in the given space of his canvas such as Are there not twelve hours of daylight.

McCahon’s addition of white paint over selected letters delivers rhythmic, aesthetic accents similar to calligraphic emphases or accents in music. Maybe here they work to strengthen the meanings of certain words or as a reflection of the idea of “stumbling”. It could also be a sort of playful, reflective cadence to complete the work. The loose canvas adds a note of submission, obedience, and meekness, appropriate to the text, while the use of capitals for all the letters of the words DAYLIGHT and THIS also act to provide particular accents of meaning and form.

I love that idea of that one cold, white, bursting line suggesting dawn light emerging, and a 'white light' angel entering the top right corner, work as if light falls through a door, offering a way through towards you. Are these marks ironic or filled with faith? Maybe faith in art?

One may speculate concerning McCahon’s use of words said to have been those used by Jesus. (John 11:9) I am not able, and have no wish here, to endeavour to provide theological or historical meaning analysis. Nor can I offer comparisons of the verses of the various Bibles with the one McCahon is said to have based his version on in this painting. It is enough for me to recognise the artful use found in all biblical versions of this verse, and of parabolic conundrums within the text, ambiguous, metaphoric meanings of the word LIGHT. The contemporary, practical, non-metaphoric meaning of the word LIGHT is, of course, the electromagnetic energy of the sun perceivable by human eyes:light as a medium of cognition in all art making. That is the meaning I find useful in addressing the concrete, empirical realities of marking and composition in this work.

I ask myself: perhaps in Are there not twelve hours of daylight McCahon was interested in investigating the nature of the human, questioning mind necessary and common to the making and cognition of all art?