- Amy Howden-Chapman2014

- Ana Iti2020

- Andrew McLeod2007

- Andy Leleisi’uao2010

- Anoushka Akel2024

- Ava Seymour2009

- Ayesha Green2022

- Ben Cauchi2011

- Benjamin Work2024

- Bepen Bhana2016

- Campbell Patterson2015

- Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss2021

- Dan Arps2014

- Daniel Malone2014

- Emily Karaka2021

- Emma Fitts2018

- Eve Armstrong2009

- Fiona Pardington2013

- Gavin Hipkins2007

- George Watson2024

- Glen Hayward2011

- Imogen Taylor2017

- James Robinson2007

- Jess Johnson2019

- Jim Speers2010

- Juanita McLauchlan2025

- Judy Millar2006

- Kathy Barry2012

- Lisa Reihana2009

- Liyen Chong2012

- Louise Menzies2016

- Luise Fong2008

- Madison Kelly2024

- Martin Basher2010

- Matthew Galloway2025

- Michael Stevenson2023

- Moniek Schrijer2021

- NELL2023

- Neke Moa2023

- Nicola Farquhar2018

- Oliver Perkins2017

- Owen Connors2023

- Regan Gentry2012

- Richard Frater2020

- Richard Lewer2008

- Rohan Wealleans2008

- Rowan Panther2025

- Ruth Buchanan2013

- Sarah Hudson2025

- Sarah Smuts-Kennedy2016

- Sefton Rani2025

- Sorawit Songsataya2018

- Steve Carr2020

- Suji Park2015

- Tanu Gago2022

- Taro Shinoda2017

- Tiffany Singh2013

- Tim Wagg2019

- Wayne Youle2019

- Zac Langdon-Pole2022

- Zena Elliott2026

Nicola Farquhar

YEAR OF RESIDENCY

September - December 2018

Gate II Nicola Farquhar x Miss Changy - November 2018

Farquhar's paintings draw on the conventions of portraiture to represent the human body as a dynamic and evolving ecosystem. They are composed of forms that resemble, variously, cellular structures, decorative foliage, and geometric motifs.

Pictured: Installation view of Nicola Farquhar, Listening, Twitching at Te Uru Waitakere Contemporary Gallery, 2020. Photograph: Sam Harnett, courtesy of Te Uru Waitakere Contemporary Gallery

Like a soggy map, or an untethered globe, the following text can be spun in any direction.

To borrow words from Bhanu Kapil, below are sentences and paragraphs that have not found their place in prose.i They were written at a subaquatic pace in response to Nicola Farquhar’s amorphous human portraits that comprised her show Listening, Twitching at Te Uru in 2020.

There is no down or up in space or in the womb.ii

I.

My eyes move like a broken compass -

a red slit…a mouth…bones…entrails...

or maybe tentacles?

Temptare : to feel, to try. The latin root of tentacle and temptation.

II.

I think of The Dream of the Fisherman’s wife. A delirious scene of clinging organs and limbs. The background of the image is scrawled with a telepathic dialogue between the entangled creatures. The woman cries out:

Oh hateful Octopus! Your sucking at the mouth of my womb makes me gasp for breath!...with the sucker, the sucker! ... Until now it was I that men called an octopus! An octopus! ... How are you able? ... Oh! Boundaries and borders gone! I’ve vanished!

III.

A memory of a man standing at a lectern flickers somewhere in my throbbing brain. He tells a half-empty lecture theatre that in early modern english the word nought held multiple meanings: nothing, wicked, vagina. Take for instance Shakespeare’s sonnet 57 in which a desperate lover is consumed by the thought of their beloved’s missed and missing sex:

But like a sad slave, stay and think of nought.

The vagina as void, absence, wound. A violent erasure of a sensing organ that takes myriad forms. It oozes, ripples, throbs, expands, contracts; grows both inwards & outwards. It is more than just an orifice, more than a 0.

IV.

And still the 0 lures me into itself; a slippery entrance and exit through which a spineless body might vanish. A black hole that obliterates all that appears rigidly defined into a matrix of vibrating particles that may be reconfigured.

Nothing is

the force that renovates

the World. iii

We are pulled forward by the sense that there is something in the nothing. A feeling of terror that is yoked to wonder.

Medieval cartographer’s would illustrate unknown territories with monstrous mythical creatures.

VI.

Hokusai’s woodblock print also goes by the name Girl Diver. Who is the diver? Girl or octopus? Boundaries and borders gone!

To dive; to plunge, to fall, to descend.

In order to deep dive toward the bottom, one must either hold their breath, or learn how to breathe underwater. But where is the bottom?

Abussos: bottomless, abyss.

If there is nothing to fall toward, you may not even be aware that you’re falling.iv Falling can sometimes feel like floating.

Descending into the abyss is disorienting. A confused sense of space and time; the edges of bodies dissolve. Ideas, language, even the phrase ‘each other’ doesn’t make sense.v

Hélène Cixous describes descent as a movement of ascending downwards; to move in both directions at once, like an ouroboros devouring itself. The writers she loves are all descenders; voyagers of dark interiors. She claims that there are two ways of clambering downwards - by plunging into the earth and going deep into the sea - and neither is easy.vi Clarice Lispector, one of Cixous’ beloved descenders, warned that it takes courage to attempt such depths - you never know what might come and frighten you.vii

Approximately 83% of the ocean is made up of what is called the abyssal zone, where there is no light. A number mirrored by the percentage of water in human lungs.

My favourite kind of darkness is the one inside us.viii

I think of Juahani Pallasmaa’s reflection that shadow inhales and illumination exhalesix and I am overcome with the dizzying thought that the sea is one endless inhalation.

I have dreamt of inhaling underneath water and this is what it feels like: panic, and then acceptance, and then elation. I am going to die, I am not dying, I am doing a thing I never thought I could do.x

A breathless elation. I’ve vanished!

VI.

In Jean Painlevé and Geneviève Hamon’s 1965 experimental short film The Love Life of the Octopus, the camera searches for the shapeshifting creature which has disappeared beneath a rock, its presence indicated only by the lapping water caused by its breathing. An eerie, arrhythmic soundscape typical of the era’s imaginings of outer space accentuates the otherworldly qualities of what the narrator calls the horrifying animal.

“You’re not a monster,” I said. But I lied. What I really wanted to say was that a monster is not such a terrible thing to be. From the Latin root monstrum, a divine messenger of catastrophe, then adapted by the Old French to mean an animal of myriad origins: centaur, griffin, satyr. To be a monster is to be a hybrid signal, a lighthouse: both shelter and warning at once.xi

In Ovid’s version of the myth, the gorgon Medusa was once a mortal maiden transformed into a fearsome creature after Posideon violated her in the temple of Athena. From the ancient greek medien, ‘to protect’, the name Medusa means ‘guardian’ and ‘protector’; a serpent-haired hybrid signal on the rocky shores. Donna Harraway contemplates what might have happened to the men turned to stone by Medusa’s gaze had they greeted her with respect and not as a monster to be slain.xii What if they had treated her as kin? Perseus ruthlessly severed her head and like an octopus who begins to die just as she spawns life, Medusa birthed the winged horse Pegasus from her mortal wound.

VII.

You need a long time to dissect me. I may be small, but I’m deep. The more you dig, the deeper it goes. Nobody has reached the bottom yet. xiii

A friend once told me she hopes to see inside a human body before she dies; to descend into the dark interior where she might encounter something beyond organs and blood. She is not a doctor, but a poet. William Carlos Williams was both, which perhaps accounts for his incisive use of words and his fascination with how beings are composed:

There is

the

microscopic

anatomy

of

the whale

this is

Reassuringxiv

VIII.

& eggs…

cells…

atoms…

Essay commissioned by McCahon House on the occasion of Nicola Farquhar's residency September - December 2018.

All images courtesy of Te Uru Waitakere Contemporary Gallery, 2020. Photograph: Sam Hartnett.

i. Bhanu Kapil. “Verge Notes.” Wildness. Issues No. 23, August 2020. https://readwildness.com/23/kapil-notes

ii. Franz Wright. “Walking to Martha’s Vineyard.” Walking to Martha’s Vineyard. (New York : Knopf, 2003)

iii. Emily Dickinson. The Gorgeous Nothings. (New York: Granary Books, 2012), 5

iv. Hito Steyerl. “In Free Fall: A thought experiment on Vertical Perspective.” The Wretched of the Screen, (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2012),13.

v. Jalal al-Din Rumi.”A Great Wagon.” The Essential Rumi. (San Francisco, CA : Harper, 1995.)

vi. Helene Cixous. Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993), 5.

vii] Benjamin Moser “Breathing Together.”Agua Viva

viii. Ocean Vuong. “The Last Prom Queen In Antarctica.” The Yale Review. Volume 109, No.1, Spring 2021 https://yalereview.org/article/the-last-prom-queen-in-antarctica

ix. Juhani Pallasmaa. The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. (Chichester : Wiley-Academy, 2005), 47.

x. Carmen Maria Machado.“Eight Bites.” Her Body and Other Parties (Minnesota: Graywolf Press, 2017), 220.

xi. Ocean Vuong On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous. (New York : Penguin Press, 2019),13.

xii. Donna Harraway, Staying with the Trouble. (Durham : Duke University Press, 2016)

xiii. Hossein Sabzian interviewed in Close-up Long Shot. Mamhoud Chokrollahi. 1996.

xiv. William Carlos Williams, ‘Some Simple Measures in the American Idiom and the Variable Foot’ from Pictures Brueghel and Other Poems, 47.

Artist Artworks

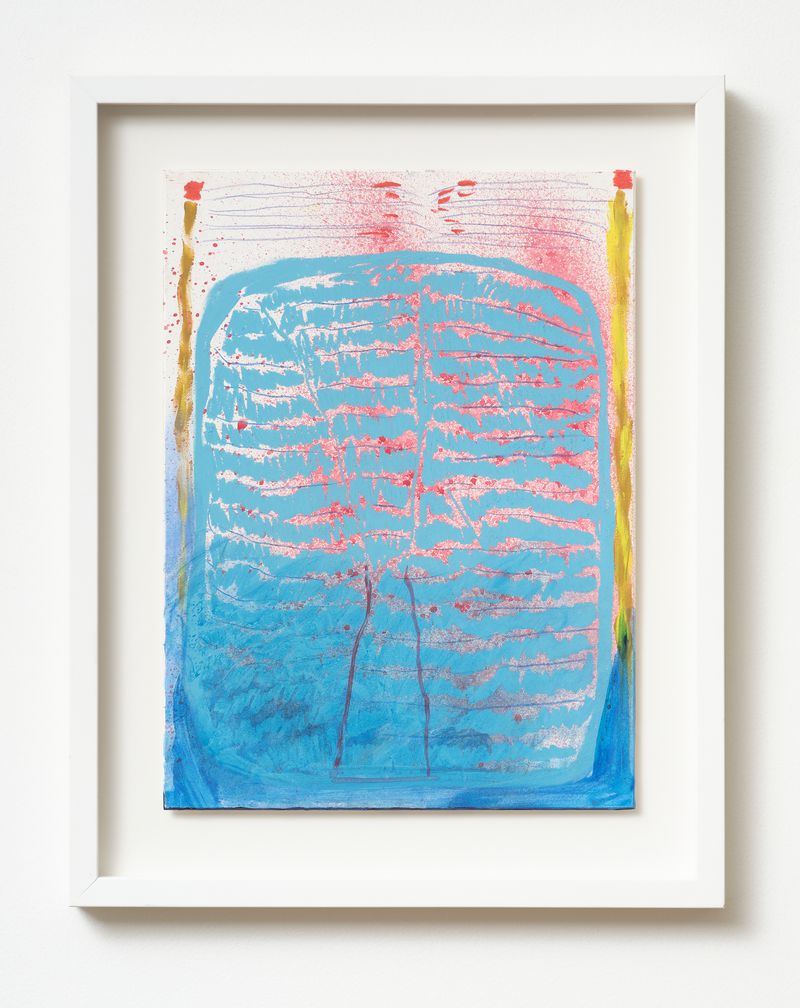

Nicola Farquhar

E.M. Noon

2019

pastel and acrylic on mattboard

480 x 380mm

$3,000 (framed)

Photo: Sam Hartnett

Contact us to purchase this edition.

Nicola Farquhar

E.M. Cap

2019

pastel and acrylic on mattboard

433 x 433mm

$3,000 (framed)

Photo: Sam Hartnett

Contact us to purchase this edition.

Nicola Farquhar

E.M. Crown

2019

pastel and acrylic on mattboard

422 x 345mm

Photo: Sam Hartnett

Collection of McCahon House Trust

Nicola Farquhar

E.M. March

2019

pastel and acrylic on mattboard

460 x 460mm

$3,000 (framed)

Photo: Sam Hartnett