- Amy Howden-Chapman2014

- Ana Iti2020

- Andrew McLeod2007

- Andy Leleisi’uao2010

- Anoushka Akel2024

- Ava Seymour2009

- Ayesha Green2022

- Ben Cauchi2011

- Benjamin Work2024

- Bepen Bhana2016

- Campbell Patterson2015

- Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss2021

- Dan Arps2014

- Daniel Malone2014

- Emily Karaka2021

- Emma Fitts2018

- Eve Armstrong2009

- Fiona Pardington2013

- Gavin Hipkins2007

- George Watson2024

- Glen Hayward2011

- Imogen Taylor2017

- James Robinson2007

- Jess Johnson2019

- Jim Speers2010

- Juanita McLauchlan2025

- Judy Millar2006

- Kathy Barry2012

- Lisa Reihana2009

- Liyen Chong2012

- Louise Menzies2016

- Luise Fong2008

- Madison Kelly2024

- Martin Basher2010

- Matthew Galloway2025

- Michael Stevenson2023

- Moniek Schrijer2021

- NELL2023

- Neke Moa2023

- Nicola Farquhar2018

- Oliver Perkins2017

- Owen Connors2023

- Regan Gentry2012

- Richard Frater2020

- Richard Lewer2008

- Rohan Wealleans2008

- Rowan Panther2025

- Ruth Buchanan2013

- Sarah Hudson2025

- Sarah Smuts-Kennedy2016

- Sefton Rani2025

- Sorawit Songsataya2018

- Steve Carr2020

- Suji Park2015

- Tanu Gago2022

- Taro Shinoda2017

- Tiffany Singh2013

- Tim Wagg2019

- Wayne Youle2019

- Zac Langdon-Pole2022

- Zena Elliott2026

Tim Wagg

YEAR OF RESIDENCY

April - July 2019

Gate IV - Tim Wagg x Cazador - July 2019

Tim Wagg (b. 1991, Masterton) is an artist currently based in Auckland, New Zealand. He graduated with a BFA (Hons) from the University of Auckland’s Elam School of Fine Arts in 2013. Working across various mediums including video, installation, and digital painting, Wagg’s work explores the intersections of politics, identity and technology within the context of New Zealand. More specifically, his work considers the tangibility and intangibility of archives and histories, and examines the visual languages surrounding moments of political upheaval or change.

Tim Wagg, Youth Portrait, 2022

4K digital video, colour sound 20:00min, sound by Ewan Collins

Commissioned by Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki 2022

Chartwell Collection, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, purchased 2022

Photo: Courtesy of the Chartwell Collection and Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 2022

It seems to me unlikely that any important portraits will ever be painted again.

John Berger, No More Portraits, 1967

Among the many functions of art is the possibility to represent a moment in history. Non-art objects do this too, but art combines the possibilities and limitations of medium, subject, intent, and skill to provide us with something more considered, more idiosyncratic. Writing in 1967, art critic John Berger described the decline of portraiture, suggesting this occurred alongside the rise of photography, new technology offering a faster, cheaper, and more accurate way to record a likeness, democratising the practice of having one’s image captured for posterity. And so painters and patrons claimed all manner of metaphysical qualities with which a painting can be suffused but a photograph cannot – “Only a man, not a machine, could interpret the soul of a sitter” etcetera.1 Many photographers would – and have – begged to differ, as did Berger himself, but it was not his intention to pit one medium against the other. Rather, he proposed that the function portrait painting had performed historically was no longer needed, or accepted, in modern society. “The function of portrait painting,” Berger explained, “was to underwrite and idealise a chosen social role of the sitter. It was not to present him as ‘an individual’ but, rather, as an individual monarch, bishop, landowner, merchant, and so on.”2

The sitter or subject for Tim Wagg’s Youth Portrait (2022) is Jadyn Dixon, a young Pākehā realtor working in Tāmaki Makaurau. Whatever beliefs a viewer may hold about realtors, it is unlikely for Jadyn to fulfil these, not because he is such an uncommonly singular subject, but because Tim has chosen to portray him as an individual, not a realtor. Throughout the video's 20 minute run time, we follow Jadyn as he navigates his work day. He arrives at his Glenfield office when the sky is still tinged dawn pink, and we arrive with him. We enter his office, a small glass-walled room furnished in shades of grey, a framed map of the world hanging behind a clean desk, Aotearoa tucked in the bottom left. We see him taking calls, working on his database, sending emails from his phone, driving through the suburbs, shooting video for a new listing. At one point, the camera zooms in on an object on Jadyn’s desk, a mounted gold credit card engraved with the maxim: YOUTHFUL TENACITY HAS ITS REWARDS.

But just as Jadyn is no one-dimensional caricature, Youth Portrait is not a linear narrative. Footage of Jadyn throughout his workday is interspersed with footage of him talking to camera at an anonymous, sparsely furnished house – perhaps his own, perhaps one of his listings – and footage of Tāmaki Makaurau seen as it so often is, from the window of a car. All the while, a voiceover of Jadyn speaking plays relentlessly, breathlessly, sound ruthlessly edited to give the listener no time for pause.

There are two things to consider here. First, this portrait is moving image, the subject captured on digital video (mechanical) but the final artwork dependent on a number of human decisions (artistic), this new medium complicating the dichotomy of painting versus photography. Second, despite the complexity with which Jadyn is portrayed, he is not positioned as the subject of the portrait. In titling the work Youth Portrait, there is the suggestion that Jadyn’s individuality is sublimated into his age, that this is a portrait of an individual but also a generation. While making this video, Tim was deeply concerned that Jadyn, or his intentions in putting Jadyn in the work, would be misinterpreted. There was a fear that audiences wouldn’t be able to see past their own scorn for capitalism (whether ironic or true) with realtors viewed as part of this machine (when of course, we all are). Because really, much of what Jadyn says is what many of us feel: the desire to succeed, to shape our own paths, to leave a legacy.3 But who is ‘us’? There is a certain cultural cringe with using the term ‘millennial’ here, but it is the most automatic descriptor for the generation Jadyn, Tim, and myself are part of. However, Youth Portrait is not a portrait of millennials en masse. It is a portrait of primarily Pākehā millennials in Aotearoa, those of us who just about remember life before the internet but not before free-market reforms of the late 80s and early 90s.

There is something tongue-in-cheek in this title, too. The word ‘youth’ for some might conjure images of a clear-eyed and dewy-skinned teenager, more Botticelli painting than Tiktok star. Or perhaps it evokes the edgy, nihilistic cast of TV shows like Skins or Euphoria. Yet the markers of ‘youth’ depicted in Youth Portrait are more akin to the twenty-somethings coding all night in The Social Network, or the finance graduates competing to succeed in HBO’s Industry. This is a representation of someone whose body hasn’t begun to ache, who can work gruelling hours and maintain collagen and enthusiasm, who has convinced themselves that putting in the hard work now will pay off later. As Jadyn says, “I don’t want to be chained to working forever, I want to build something that can create freedom.”

The potency of Youth Portrait is that it is a portrait made in the dominant medium of the time, digital video, crafted to resemble not an art video, but reality TV, a genre extant since the 1940s yet now hardly recognisable from its early forms, so responsive has it been to the ebbs and flows of society and culture.4 Through the use of quick cuts, man-to-man coverage, a mix of smooth and dynamic gimbal and handheld camera movements, confessional-style footage of Jadyn speaking to camera and a pulsating digital soundtrack, Tim has co-opted the frenzied aesthetic of a genre that sociologist Junhow Wei argues is “defined by its lack of moral cleanliness.”5 In mimicking a form that markets itself on showcasing reality in a way that can only be achieved through dubious ethical practices, Youth Portrait asks to be considered on these terms, as a complex and inevitably flawed document of a person, a time, and a place.

By the end of his essay, Berger has come to the conclusion that the incompatibility of portraiture and modern life is indicative of a “more general crisis concerning the meaning of individuality.”6 In 2023, the notion that a portrait, painted or otherwise, might reveal much about a known person is a non sequitur. Our search for truth in the representation of an individual comes from watching a show and questioning what parts are real, how they are real, what we mean by real when perhaps the most defining feature of both reality TV and digital video is the way it can be modified and manipulated.7 In a recent episode of her podcast Give Them Lala, Vanderpump Rules star Lala Kent explains that while everything we see on the show is ‘real’, filming schedules mean she is forced into close quarters with people she’d normally avoid – say, someone who accused her of being a homewrecker a few days ago, or a disgusting man you slept with after an 8-hour day of drinking and filming. Under these conditions, Kent explains, you do and say things you wouldn’t usually:

Day to day, if I’m not connecting with someone, I have the option to be like, I’m not kicking it with them. When we’re filming it’s like we have a group thing that we’re doing so you have to come… I don’t want to say forced because we’re not forced, but at the end of the day we’re here to film a TV show, so you’re seeing people for who they are but in situations that maybe they wouldn’t normally put themselves in. You have to separate reality from reality.8

This is before we even consider the ever-shifting imperatives to make good TV, to stay on the show, to be iconic. For Tim, the form of reality TV is perfect for encapsulating this contemporary moment for the way the production of such a highly manipulated environment creates a new reality.

* * *

So landscape painting, for the first settlers in New Zealand as for us, was a way of inventing the land we live in…

Francis Pound, Frames on the Land: Early Landscape Painting in New Zealand, 1983.9

Tim didn’t set out to make a portrait. This work was always intended to be about the landscape, rooted in discussions from the likes of Francis Pound and Claudia Bell about the invention of the New Zealand landscape and how this connects to the ideation of a Pākehā identity. Out of this consideration of the legacies of colonialism in the present moment and watching real estate centred reality TV shows such as Bravo’s Million Dollar Listing, Tim became interested in Aotearoa’s housing market and began searching for a real estate videographer to shadow and potentially collaborate with. This is how he first came across Jadyn, starring in his own advertising video on YouTube in which he drives a jet ski around Rangitoto Island in a grey suit, jumping into the crystal clear waters and walking onto a white sand beach, arms outstretched as if to say, isn’t this sublime?10

Describing Augustus Earle’s Distant View of the Bay of Islands (1827), art historian Francis Pound focuses on the figure standing with his back to the viewer. “The figure is European – the immaculately white hate, the burdenless back, the trousers and coat are sufficient signs of that. It stands, absolutely still, and gazes into the landscape, while Maori (sic) figures move in the land. This stillness, this movement, is significant, for landscape painting, the pictorial attitude to the land, stopping still just to look at it, to see it as a picture, is purely an imported convention.”11 Without a knowledge of our colonial art history, Jadyn’s promotional video mimics its conventions, ones that position the land as a commodity to be surveyed and quantified. Just as the paintings and sketches of Earle and his contemporaries were used to incite British capitalists to emigrate to New Zealand, real estate agents draw on the beauty and mythology of the New Zealand landscape to sell property, but also to illustrate their own personal visions. Just before he jumps from the jet ski into the ocean, Jadyn tells the camera, “I would love for you to be a part of my journey, and my legacy.”

Many of the colonial artists whose work hangs in our national galleries today were not, first and foremost, artists. Pound describes how Abel Tasman illustrated his voyage journals with coastal profiles, how naval training included drawing, and how Cook himself made profiles along with his artists and naturalist. This is all to suggest that such works from the likes of Charles Heaphy, William Fox, and so on were not considered art (as we understand the term) at all; were in fact more akin to studies of new plants, made for purposes of identification, description and at times, promotion of New Zealand’s beauty and abundance to prospective settlers. Indeed, Pound quotes museum professional Cheryll Sotheran as saying “many of the early landscapes of Fox emphasise not so much unspoiled primeval nature, but potential productivity”, an observation amply supported by Fox’s own enthusiastic promotion of the colonial project. He describes the “productiveness” of the land as second to none and explains that in New Zealand, the emigrant will find “an open sphere for the employment of his labour or capital, where industry, prudence, and perseverance are not baulked of their reward,” and how “generations to be born will feel its benefit.”12

The echo of Fox’s words can be felt throughout Youth Portrait, from the gold engraved credit card on Jadyn’s desk to the metaphor of exploration he uses to describe his own work ethic: “When the tide goes out or things get tough, you soon see who’s willing to stay and make things happen… the ones who are going to risk putting everything on the line or sailing through the rough storm to get to the promised land.” Jadyn suggests his motivation to succeed comes from his family, citing his grandfather and father as leaving legacies for him to fulfill. Yet in Aotearoa, this desire to build from the ground up and make it on your own are themselves legacies of the colonial period that have become part of the national psyche, one that Jadyn encapsulates when he explains, “I just knew I wanted to be involved in something bigger than myself, prove to myself that I had the ability to make it on my own. I think consciously I had to do that but also subconsciously it was kind of embedded in me from what I’d seen growing up.”

* * *

Youth Portrait opens with the deep quiet blue of the early morning harbour, situating us, as we always are in Aotearoa, by the ocean. This is where it all began, from the primordial soup to the arrival of the first waka to the Endeavour appearing on the horizon. Here are the coastlines artists and navigators sketched, the isthmus, the volcanic cones, many now quarried away. Rather than offering a “window to the world”, Tim’s video presents the landscape as it appears most often to those of us who inhabit the country today: through the car window.13 From this vantage point, we see the sun shimmering gold on the water, the dark rush of foliage blurring as we drive by, the smudge of mountains in the distance. But mostly, we see other cars, car parks as far as the eye can see, grey metal structures, suburbia sprawling towards the green, identical new build houses rising, the city spilling out onto the water, the harbour reshaped by jetties and ports. Describing a Fox painting of the Tiraumea Valley (1846), Pound admits that it offers the pleasures of Sublime emotion – vastness, emptiness – but suggests the feeling is tainted when one considers that it was painted on a surveying mission through land previously touched only by Māori. If we divorce this painting from its context, we might be able to look at it and say, isn’t this sublime? But as Pound writes, for Fox and the colonial project, this painting could have been used to say “Look! All this could be ours!”14 The project of Youth Portrait is less clear-cut. It is both landscape and portrait, but it is also neither, something more mutable and unsettled; it’s not trying to sell anything. There is no statement, perhaps just a tentative, hopeful question of where do we go from here?

[1] Berger, “No More Portraits”, 166.

[2] Berger, 167.

[3] As of the most recent report in 2020, Aotearoa is ranked number one in the world for our ease of business regulations, according to the World Bank Doing Business report. There is a longstanding culture of entrepreneurialism and small businesses here that dates back to settlement, with colonial New Zealand being advertised to the British capitalist class as a place to inhabit and create wealth from the land through farming and the export of goods back to Britain. “Because there was no capitalist development already here, it was much cheaper and easier to start a profitable venture here than it was back in Europe.” As Jadyn puts it in the video, “New Zealand as a place is more like a training ground, it’s off the radar, it’s not as known about but we do have a lot of good things going on here for the economy, good for business, the opportunities that are out there.” Tim’s own day job and those of his wider milieu are testament to this, a circle of contractors, small business owners, freelance writers, designers, artists and programmers.

World Bank Group, Doing Business 2020: Comparing Business in 190 Economies, p4. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/32436/9781464814402.pdf

Rākete et al. “Settler-colonialism in Aotearoa.” https://organiseaotearoa.nz/2020/01/30/settler-colonialism-in-aotearoa/

[4] As Junhow Wei points out, many of the earliest TV shows such as Candid Camera (1948) include ordinary people in unscripted situations. Reality TV scholar Misha Kavka, among others, cites 2004 as the year when reality TV began to “explode across television broadcast schedules in ever-expanding subgenres.” Wei discusses the political-economic context that spawned this proliferation, citing cheap production costs (including reliance on non-union production labour and unknown talent) as one reason, as well as the sale of templates (for example, competition formats like Big Brother and Idol or even docu-series such as Real Housewives) which have been tested that can be tailored to the specifications of new markets.

Wei, “Good Character: Reality Television Production as Dirty Work,” 15-16.

Kavka, “Reality TV: Its contents and discontents.”

[5] Wei, 18.

[6] Berger, 170.

[7] Thomas Elsaesser, “Digital Cinema: Convergence or Contradiction.”

[8] Lala Kent, “All Things Bravo with Lara Marie Schoenhals.”

[9] Francis Pound, Frames on the Land: Early Landscape Painting in New Zealand, 14

[10] Jadyn Dixon, https://www.jadyndixon.co.nz/video-gallery?wix-vod-video-id=34b842d6beff429f96799ac7782c1362&wix-vod-comp-id=comp-jxmlr8ua

[11] Pound, Frames on the Land, 12.

[12] William Fox, Colonisation and New Zealand, 12

[13] Pound, 12.

[14] Pound, 44

References

Bell, Claudia. Inventing New Zealand: Everyday Myths of Pakeha Identity. Auckland: Penguin, 1996.

Berger, John. “No More Portraits” (1967) in Landscapes: John Berger on Art, edited by Tom Overton, 165-170. United Kingdom: Verso Books, 2016

Dixon, Jadyn. “Jadyn Dixon.” Accessed March 4, 2023. https://www.jadyndixon.co.nz/video-gallery?wix-vod-video-id=34b842d6beff429f96799ac7782c1362&wix-vod-comp-id=comp-jxmlr8ua

Elsaesser, Thomas. “Digital Cinema: Convergence or Contradiction.” In The Oxford Handbook of Sound and Image in Digital Media. Edited by Carol Vernallis, Amy Herzog, and John Richardson England: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Fox, William. Colonisation and New Zealand. London: Smith, Elder & Co., 65, Cornhill. 1842.

Kavka, Misha. “Reality TV: Its contents and discontents.” Critical Quarterly, 60, no. 4. (2018) 5-18. https://doi.org/10.1111/criq.12442

Kent, Lala, host. “All Things Bravo with Lara Marie Schoenhals,” Give Them Lala (podcast). January 25, 2023, accessed March 6, 2023. https://podcasts.apple.com/nz/podcast/all-things-bravo-with-lara-marie-schoenhals/id1494722390?i=1000596448835

Pound, Francis. Frames on the Land: Early Landscape Painting in New Zealand. Auckland: William Collins Publishers Ltd, 1983

Pound, Francis. The Invention of New Zealand: Art and National Identity, 1930–1970. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2009.

Rākete, Emilie, Aaliyah Zionov, Sophie Morgan, Jessica Lim, Cáit Ó Pronntaigh, Vanessa Arapko, Lisandru Grigorut. “Settler-colonialism in Aotearoa.” Organise Aotearoa. Accessed March 4, 2023. https://organiseaotearoa.nz/2020/01/30/settler-colonialism-in-aotearoa/

Vernallis, Carol. “Accelerated Aesthetics: A New Lexicon of Time, Space, and Rhythm.” In Unruly Media: YouTube, Music Video, and the New Digital Cinema (2013; online edition, Oxford Academic, 26 Sept. 2013), p708.

https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199766994.002.0008Wei, Junhow. “Good Character: Reality Television Production as Dirty Work.” PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 2016. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2094

World Bank Group. “Doing Business 2020: Comparing Business in 190 Economies.” Accessed March 4, 2023. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/32436/9781464814402.pdf

Artist Artworks

Tim Wagg

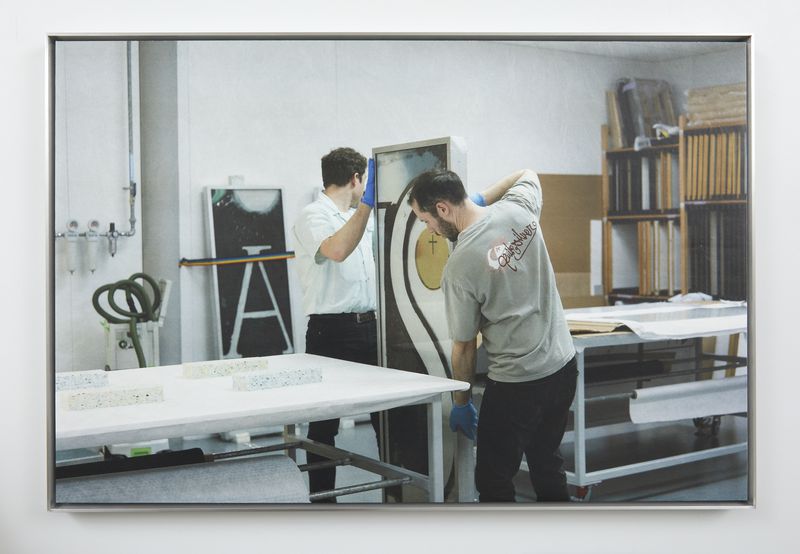

Working towards meaning (A7300142.arw)

2020

digital print on tyvek, aluminium frame, edition of 3

412 x 612mm (framed)

$950.00 (framed)

Contact us to purchase this edition.

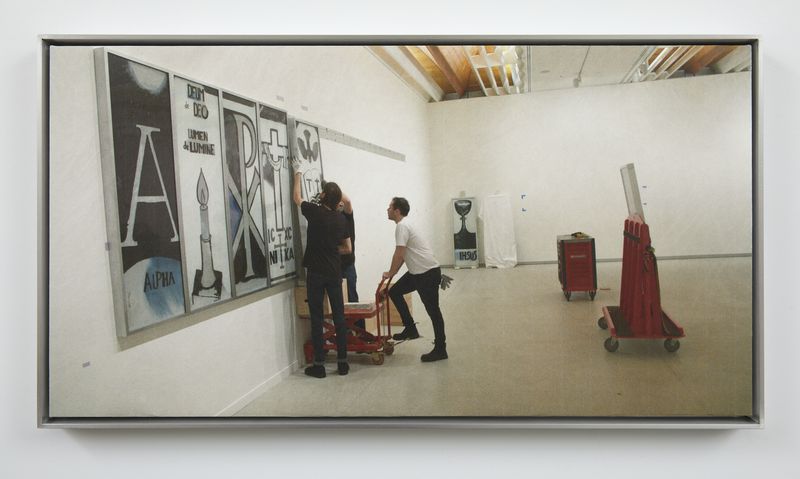

Tim Wagg

Working towards meaning (977_0024.MXF)

2020

digital print on tyvek, aluminium frame, edition of 3

228 x 421mm (framed)

$700.00 (framed)

Tim Wagg

Working towards meaning (519_0212.MXF)

2020

digital print on tyvek, aluminium frame, edition of 3

412 x 612mm (framed)

$700.00 (framed)