- Amy Howden-Chapman2014

- Ana Iti2020

- Andrew McLeod2007

- Andy Leleisi’uao2010

- Anoushka Akel2024

- Ava Seymour2009

- Ayesha Green2022

- Ben Cauchi2011

- Benjamin Work2024

- Bepen Bhana2016

- Campbell Patterson2015

- Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss2021

- Dan Arps2014

- Daniel Malone2014

- Emily Karaka2021

- Emma Fitts2018

- Eve Armstrong2009

- Fiona Pardington2013

- Gavin Hipkins2007

- George Watson2024

- Glen Hayward2011

- Imogen Taylor2017

- James Robinson2007

- Jess Johnson2019

- Jim Speers2010

- Juanita McLauchlan2025

- Judy Millar2006

- Kathy Barry2012

- Lisa Reihana2009

- Liyen Chong2012

- Louise Menzies2016

- Luise Fong2008

- Madison Kelly2024

- Martin Basher2010

- Matthew Galloway2025

- Michael Stevenson2023

- Moniek Schrijer2021

- NELL2023

- Neke Moa2023

- Nicola Farquhar2018

- Oliver Perkins2017

- Owen Connors2023

- Regan Gentry2012

- Richard Frater2020

- Richard Lewer2008

- Rohan Wealleans2008

- Rowan Panther2025

- Ruth Buchanan2013

- Sarah Hudson2025

- Sarah Smuts-Kennedy2016

- Sefton Rani2025

- Sorawit Songsataya2018

- Steve Carr2020

- Suji Park2015

- Tanu Gago2022

- Taro Shinoda2017

- Tiffany Singh2013

- Tim Wagg2019

- Wayne Youle2019

- Zac Langdon-Pole2022

- Zena Elliott2026

Taro Shinoda

YEAR OF RESIDENCY

September - December 2017

Taro Shinoda, Auckland Cityscape and Supermoon, 2017, video (1:05:00)

McCahon House’s inaugural international resident Taro Shinoda was selected in partnership between McCahon House Trust and Tobias Berger, Head of Art, Twai Kim Centre for Heritage and Art, Hong Kong. Taro’s ‘post residency exhibition’ was the performance of Lunar Reflection Transmission Technique with Uriel Barthélémi at Corban Estate Art Centre during Auckland Art Fair, 2018. Taro is a Professor of Fine Art at Tokyo University of the Arts, which also involves teaching blocks at Central St Martins (London). During his residency Taro presented to students at The University of Auckland's Elam School of Fine Art and hosted an open studio.

Taro Shinoda’s work evidences a sensory relationship with nature and the intersection between art and science in the natural world. His work is universal in its reach and he has a significant international profile. Shinoda’s application conveyed his interest in connecting with Māori in much the same spirit as he has already done with Aboriginal communities leading up to his work for the 20th Sydney Biennale: The Future is already here? It’s just not evenly distributed… His practice reflects his deep consideration of nature, humanity, philosophy and science and engages in a highly conceptual and experimental artistic process that traverses video, sculpture, installation, performance, painting and photography.

Taro Shinoda, Engawa Site Project (ESP), 2004–05, steel, aluminium, paint. Courtesy of the artist

Taro Shinoda, Abstraction of Confusion, 2016, clay, pigment, ochre, tatami mats, dimensions variable, as installed at the Art Gallery of New South Wales for the 20th Biennale of Sydney. Courtesy of the artist

Taro Shinoda, Model of Oblivion, 2005–07, mixed media, 4575 x 2600 x 1830mm, as installed at Mori Art Museum, Roppongi Hills, Tokyo, Japan, 2010. Courtesy of the artist

Kate Brettkelly-Chalmers meets Tokyo artist Taro Shinoda in French Bay, Auckland, and hears his thoughts on possums, gumboots and the parable of the frog in the well.

“I have found that the research doesn’t work if it happens before arriving,” says Taro Shinoda, newly installed as the first international recipient of the McCahon House Artists’ Residency in French Bay. While brimming with ideas for new projects, Shinoda is carefully exploring a number of different possibilities for his time here – looking for stories that will lead him toward a particular theme or artistic topic. “In my first morning here,” he says, “I woke up early and I met a neighbour who was wearing rubber boots, or something. He looked like he was going to the mountains.” Shinoda smiles when I tell him that we call these ‘gumboots’.

“I asked this man wearing gumboots what he was doing and he told me that he was out hunting rats. I wanted to know why, so he told me about the history of New Zealand – about how isolated the country has been, how there are no indigenous mammals here and how animals like rabbits and possums were introduced for their fur, and have since become a problem for the environment. At the same time, possum fur is now used in combination with wool from merino sheep to produce yarn. This is a very local topic, but a similar economic trick or cycle has occurred in a number of other places – including Japan – and that is something I am very interested in.”

Trained in Japanese landscape and garden design, Taro Shinoda makes films and installations that explore connections between the natural environment and man-made structures. The Tokyo artist was chosen from a handful of international applicants for a three-month stay in a purpose-built studio and apartment complex nestled into the bush alongside Colin McCahon’s French Bay cottage.

McCahon House Trust Director Vivienne Stone explains that Shinoda has come to New Zealand at the recommendation of Tobias Berger, former director of Artspace in Auckland and current Head of Art at the Tai Kwun Centre for Heritage and Art in Hong Kong. After focusing on local artists for its first 10 years, Stone says the trust was keen to open the “residency to an established artist based in the Asia Pacific region who might bring new ideas, networks and relationships to the New Zealand art community”. She hails the international residency as “an exciting addition to the contemporary art conversations that are happening in this country”.

Shinoda will be most familiar to New Zealand audiences for his installation Abstraction of Confusion (2016) exhibited at last year’s Sydney Biennale. In this work, Shinoda placed a wooden platform and traditional tatami mats in a small exhibition space where the walls had been treated with a fresh wash of white clay and red ochre – materials that the artist learnt about while visiting indigenous communities in Yirrkala, Arnhem Land, in Australia’s Northern Territory. Over the course of the exhibition, the pale surface of the walls began to dry and crack, gradually crumbling away to reveal an earthy red pigment beneath.

While these natural materials were particularly compelling, Shinoda’s wider practice engages a remarkably diverse range of media. The Engawa Site Project (2004–05) is a Japanese engawa platform – the traditional portico that separates house and garden – on wheels, by which viewers can sit and contemplate different environments at a slight remove. The sculpture Model of Oblivion (2005–07) takes the form of a pristine white rock face dripping with a brilliantly viscous red paint. The Lunar Reflection Transmission Technique projects (2007–ongoing) are based on images of the moon filmed from different cities around the world using a simple cardboard telescope.

Many of these sculptures and installations make use of fabrication skills that Shinoda acquired while working for several years for a manufacturer of steel frame supports. Shinoda explains that there was no work for garden designers in Japan after the financial bubble of the 1980s abruptly burst and caused a great downturn in the country’s economy. These different work experiences inform his unique artistic interest in subjects that are conventionally opposed in Western thinking: nature and artifice, landscapes and manufacturing, gardening and machines.

Given these divergent themes, I ask Shinoda if he considers himself an environmentalist. While his works address the relationship between nature and human industriousness, he does not champion a specific environmental cause. Shinoda insists that “the point is not what is good or bad. We human beings are part of nature, so anything that we do is also ‘natural’. But at some point we have to stop, step back and think about the consequences of what we are doing from a higher position. I want to offer this perspective – to reflect on the way we are currently living.”

This need to gain perspective on everyday human activities is motivated, in part, by Shinoda’s early training. The artist was greatly affected by the words of one teacher who had spent his life as a bonsai instructor and seemed to be following the path of the ‘frog who lives at the bottom of the well’ – a Japanese allegory for living a narrow and confined existence. This teacher pointedly reminded Shinoda that the frog can always look up at the night sky from deep within the well, thereby transcending the human viewpoint that remains bound to the surface of the earth. Shinoda says that “because the earth is constantly spinning around, the frog can see the whole universe from the bottom of the well. I was really impressed by this idea. I thought that maybe I could do something really deep and gain another perspective on things – another understanding. These words changed my life.”

I ask how this perspective might relate to a work like Abstraction of Confusion, which invites the viewer to contemplate solid white walls that appear to be slowly crumbling. Shinoda replies by referring to another big, philosophical narrative: the premise that the breadth of human existence is but a brief and finite moment compared to the deep timescales of the earth. He suggests that in the future, the human story will only be represented by a few centimetres in the sedimentary record of geological epochs.

“For the piece at the Sydney Biennale I tried to provide a way to feel more at ease with the idea that our civilisation is really fragile. Nothing will last forever. I want to allow people to reflect on the impermanence of things. For me, art is not an economic product, but a kind of tool for achieving a higher-level perspective. I am always trying to create a space of distance. If you go up a tall building like a skyscraper or take the view from a satellite, all the people on the ground below look like ants. This is an important perspective. I want to create a simple platform where people can adopt this point of view.”

Talking to Shinoda in the very first week of his residency, it is still early days when it comes to how he might offer a different perspective on New Zealand’s unique relationship to the land, economy and environment. Several projects are in the pipeline. Shinoda has developed a strong international reputation for creating ambitious installations and many are hoping that come autumn or winter 2018, Auckland will be home to one of them.

This article was first published in Art News New Zealand Summer 2017 artnews.co.nz

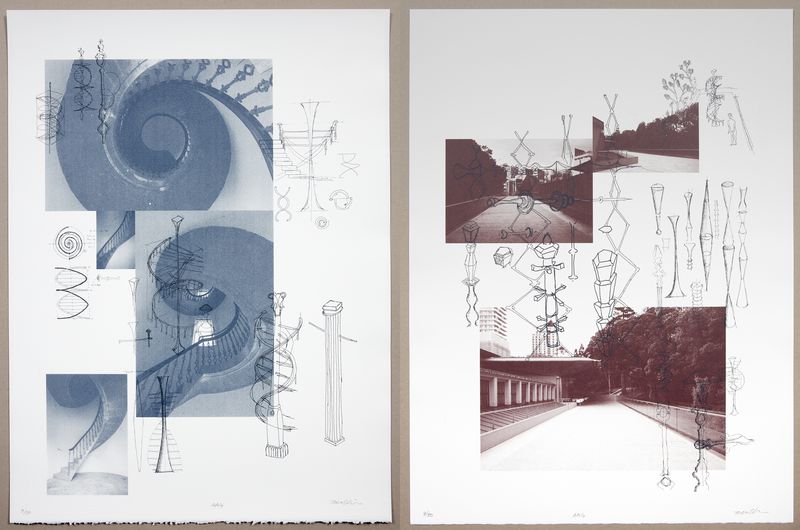

Artist Artworks

Taro Shinoda

AAG

2017

screenprint on paper, edition of 50

diptych, 760 x 560mm each

$1,150 (unframed)

Contact us to purchase this edition.