Tomorrow will be the same but not as this is: McCahon, O’Reilly, Brasch, Baverstock and the McDougall Gallery

Peter Simpson

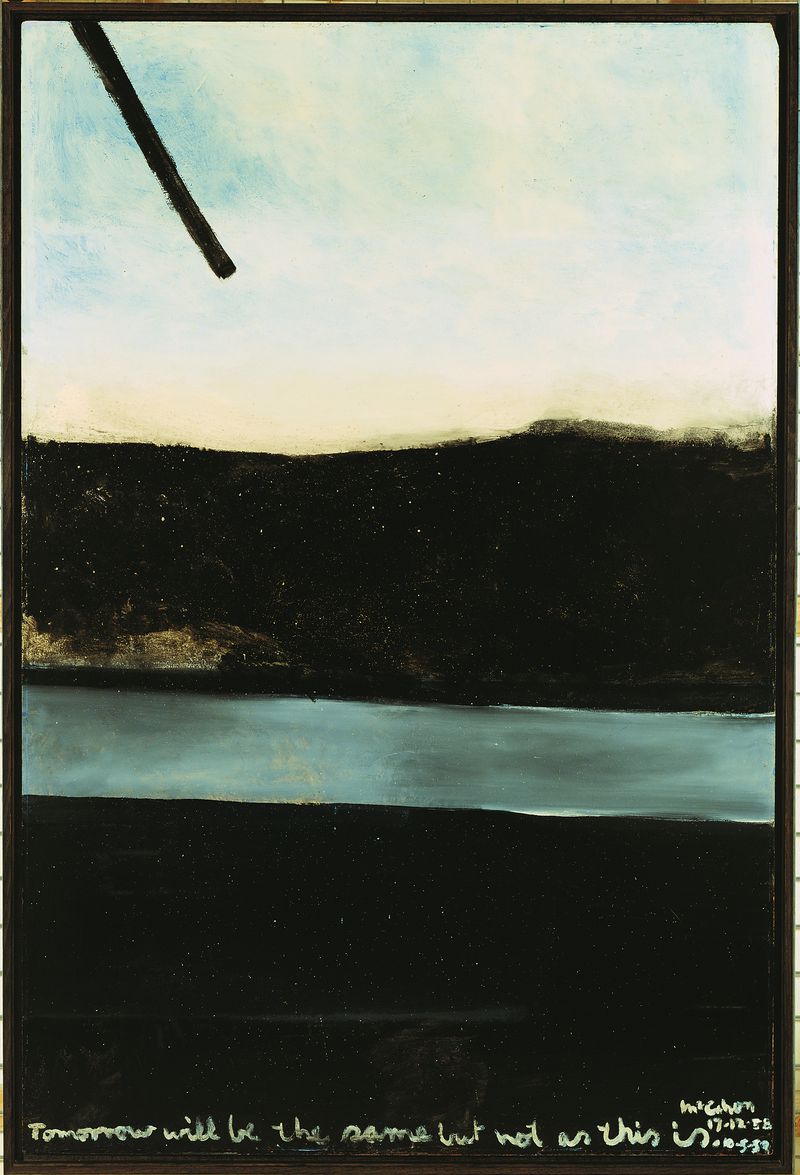

Tomorrow will be the same but not as this is (1958-59) – hereafter referred to as Tomorrow – is rightly one of Colin McCahon’s best known paintings, often exhibited and reproduced and nearly always on display at Christchurch Art Gallery (CAG). The full story of how it entered the collection of the McDougall Art Gallery – predecessor of the CAG – in 1962 is not so well known, but is worth telling from a number of perspectives. It says much about the pivotal moment in McCahon’s career it represents, about the polarised reception of his work sixty years ago, about overcoming institutional resistance to his work, about the wide following he had among fellow artists (especially in Christchurch), and it reveals, too, an instructive clash of sensibilities between two of McCahon’s closest friends and most important supporters and collectors – Charles Brasch (1909-73) and Ron O’Reilly (1914-82).

Tomorrow will be the same but not as this is, enamel and sand on board, 1958-59, CAG

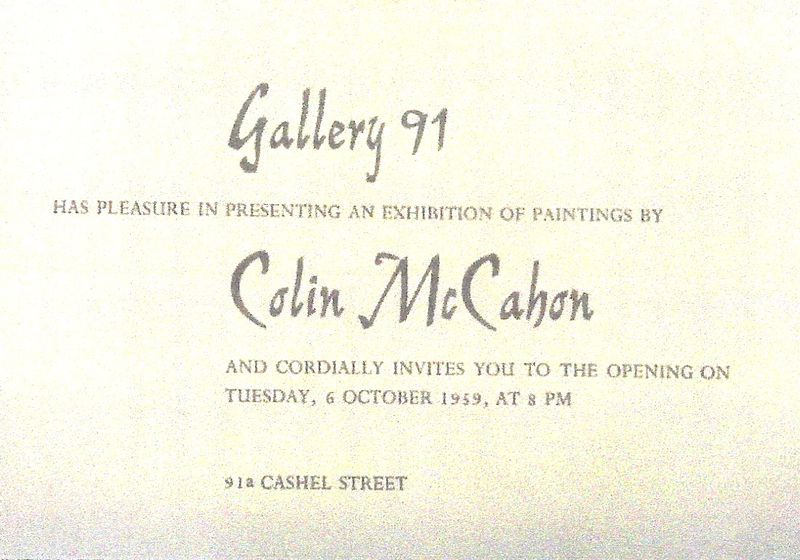

Invitation to exhibition at Gallery 91, 6 October 1959

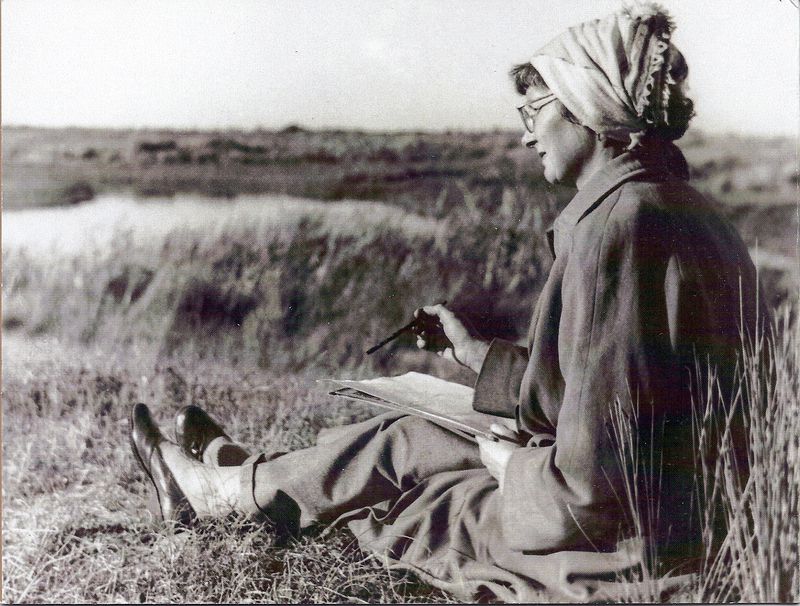

Doris Lusk in 1959 (photograph courtesy of Patrick Holland)

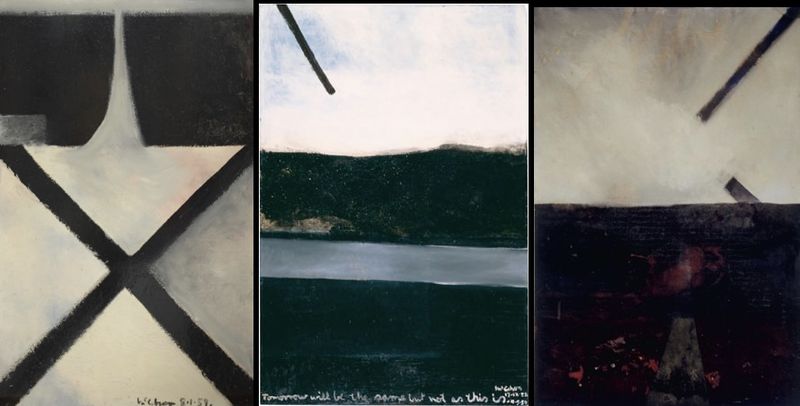

Left: Cross, 1959, AAG; Centre: Tomorrow, 1958-59, CAG; Right: A landscape – Fragments of a Cross, 1959, pc

Robert McDougall Art Gallery, Christchurch, 1950s (Christchurch City Libraries)

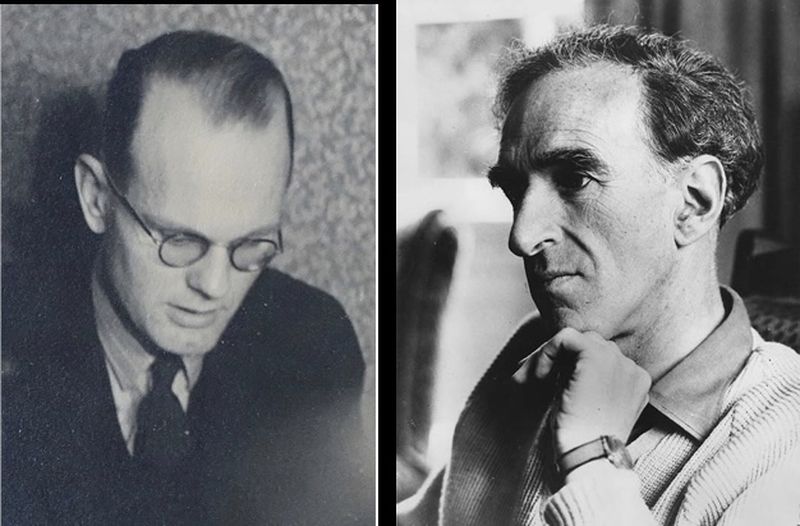

Left: Ron O’Reilly (O’Reilly Estate); Right: Charles Brasch (Hocken Collections)

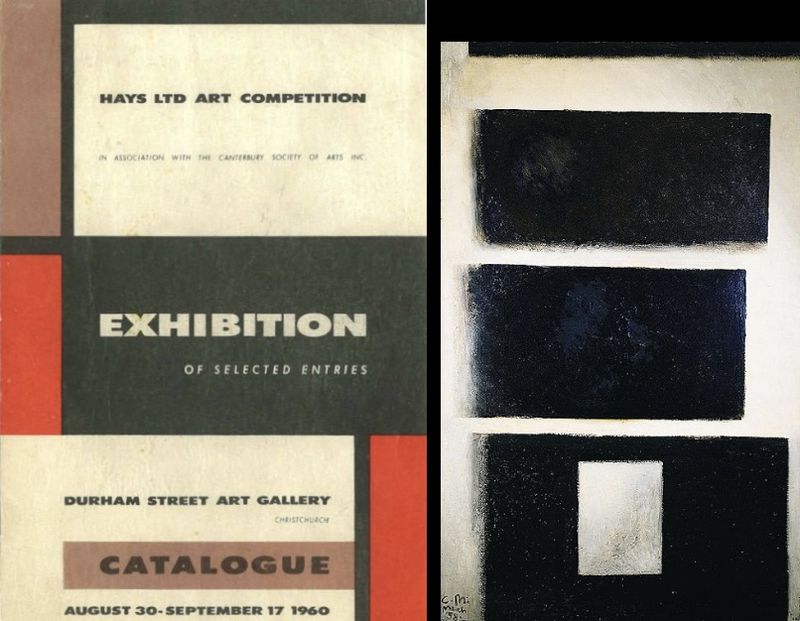

Left: Catalogue, Hays Ltd Art Competition, 1960 (Christchurch Art Gallery); Right: Painting, oil on hardboard, 1958, Fletcher Trust

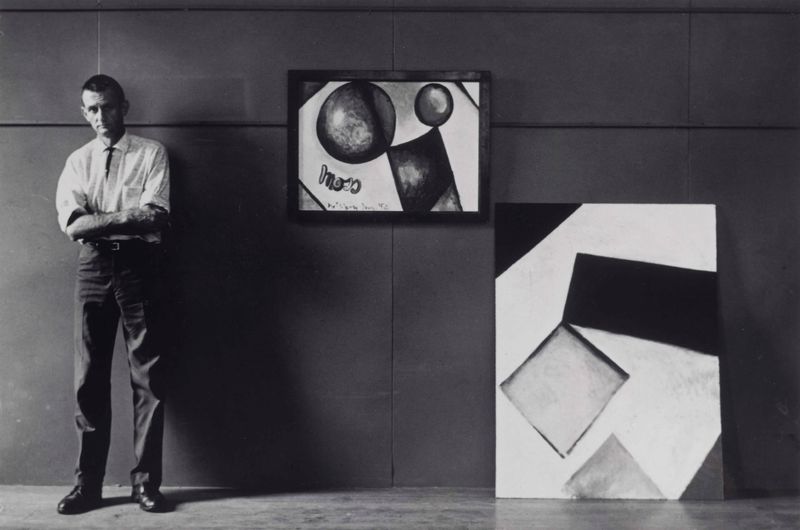

Colin McCahon in 1961; Bernie Hill photograph, E.H. McCormick Research Library, Auckland Art Gallery

W.S. Baverstock in the 1960s (Early New Zealand Photographers)

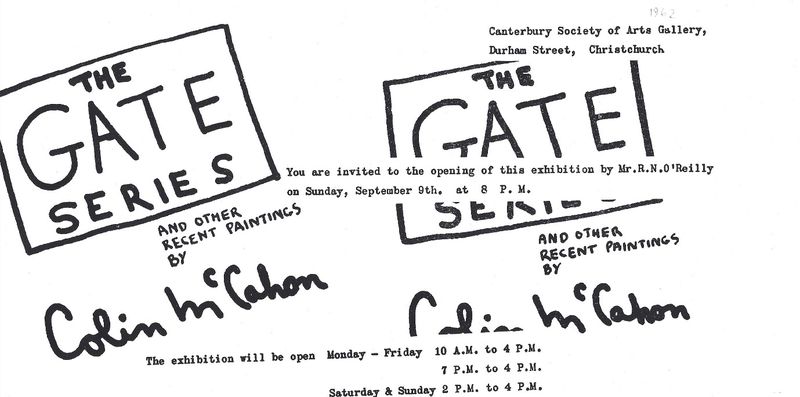

The Gate Series, exhibition invitation, 1962, E.H. McCormick Research Library, Auckland Art Gallery

Tomorrow will be the same but not as this is (1958-59) – hereafter referred to as Tomorrow – is rightly one of Colin McCahon’s best known paintings, often exhibited and reproduced and nearly always on display at Christchurch Art Gallery (CAG). The full story of how it entered the collection of the McDougall Art Gallery – predecessor of the CAG – in 1962 is not so well known, but is worth telling from a number of perspectives. It says much about the pivotal moment in McCahon’s career it represents, about the polarised reception of his work sixty years ago, about overcoming institutional resistance to his work, about the wide following he had among fellow artists (especially in Christchurch), and it reveals, too, an instructive clash of sensibilities between two of McCahon’s closest friends and most important supporters and collectors – Charles Brasch (1909-73) and Ron O’Reilly (1914-82).

I Colin McCahon: Recent Paintings, October 1959

Tomorrow was first exhibited in the exhibition Colin McCahon: Recent Paintings November 1958 - August 1959 at Gallery 91 in Christchurch in October 1959. This exhibition was one of the most important in McCahon’s career. It brought together – with the exception of The Wake (1958) which was exhibited earlier2 – much of the new work made during a prolific ten-month period after his return from a visit to the United States with his wife Anne in April-August 1958. McCahon himself referred to having produced ‘a flood of new work’ in a letter to Brasch (15 July 1959)3. The exhibition included the eight Northland panels on unstretched canvas, 35 Northland drawings in Chinese ink, Northland triptych in enamel on board, two sets of Numerals in Chinese ink – One to Ten and One to Five – the Elias Series (14 items, mostly Solpah or Butex on board)4, two ‘homage’ pictures, Toss in Greymouth and John in Canterbury (both Butex on board), a couple of stand-alone works: Northland and I one (Butex on board) and a miscellaneous group of about a dozen landscapes/abstracts (Solpah on plywood or hardboard). Tomorrow belongs to this last group but stands somewhat apart from the others because of its exceptional size. The catalogue lists 36 items but when multiples are counted the total is 92.5

The miscellaneous ‘landscapes’, are listed as numbers 8 - 19 in the catalogue.6 The paintings range widely in size, the smallest being 544 x 426mm, the largest (Tomorrow) being 1824 x 1217mm, with half a dozen size variations in between. All are painted in the commercial enamel floor paint Solpah (sometimes mixed with sand) on either plywood or hardboard. A couple refer in their titles to French Bay (Black white French Bay, Black & white French Bay) while eight have the word ‘landscape’ in their titles (e.g. Black, white and orange landscape, Landscape grey sky, red earth, A landscape – Fragments of a cross etc.). Most of the paintings are precisely dated as to day and month on the back, and were painted between 7 December 1958 and 9 February 1959, a two month period. Tomorrow is unusual in carrying a double date: 17-12-58 – 10-5-59, and for extending beyond the December-February dates shared by the others.7 A possible reason for this difference is given in McCahon’s only published comment about the work, in his 1972 Survey Notes where he describes painting the work in his garage studio at Titirangi:

This was unfortunate in that it wouldn’t go right, and I got madder and madder (which shows the childish mentality of painters). I hurled a whole lovely quart tin of black Dulux at the board and reconstructed the painting out of the mess… (p. 26)8

As to whether the paintings in this miscellaneous group are ‘abstracts’ or ‘landscapes’ or a combination, there is an apposite comment by McCahon made to Brasch in the month in which many of the group were painted:

Immediate painting is very mixed – am swinging between greater realism and much freer abstraction & just can’t settle either way. I did expect to have a difficult time but not as difficult as it has been since coming back. After Xmas will probably settle down. This manuka flowering season is always hard, my paint becomes romantic & it just doesn’t seem to suit me. (4 December 1958)9

There is also a relevant comment made by John Caselberg in a letter to Brasch in the new year:

You may be interested to hear of the painting which somehow over Xmas Colin has done. In spite of being beleaguered by visitors, building an additional room, etc. To my mind, it is some of the most powerful & beautiful of all his work. In subject it harks back to & develops from Canterbury; from the last Crucifixions & Canterbury landscapes, & his explorations of plain, horizon & sky; of horizon & space. For years, I think, in a way this has been his subject & concern. These paintings are stark, like all his work; but they are so delicately painted. Mostly black & white; but with many variations on this, & many traces of delicate colour. His artistic vision is so fierce & sharp: so unlike anything else in N.Z. unless it is Maori art itself.10 (13 March 1959)

McCahon told O’Reilly in March, echoing Caselberg’s comment about the relationship to earlier paintings:

Sorry I couldn’t show you any new paintings owing to flu & general rush – they are quite different to any of the more recent things having nothing to do with the Titirangi landscape this time but rather more like earlier southern paintings. (11 March 1959)11

McCahon was fully aware that his Gallery 91 exhibition would surprise his viewers with unexpected developments in his practice. He told Brasch somewhat diffidently:

There is just a chance that I may get down to Chch in October myself – I hope I can make it. Not that I wish to be too closely associated with this exhibition. It’s not going to be what anyone expects at all, and sadly for André [Brooke] not saleable – at least I don’t think so. (19 August 1959)12

To Woollaston he wondered indecisively about the quality of his new work:

Am hoping to get down for my Gallery 91 show in October – all new work & I’d like to see it all together. I can’t decide whether it’s good or not. Sometimes one knows at once – other times not at all. This is one of the latter occasions. (27 August 1959)13

In the end McCahon was unable to get to Christchurch for the exhibition in October but was told about its reception by O’Reilly who sent reviews from the Christchurch papers; the reviews were positive but there was ‘resistance’ from some others:

Herewith some reviews: The show is quite a turning point in the lives of many around here so that the resistance of others is understandable and indeed a part of the context which could hardly be different if what you seem to be crying out against has the truth it seems to some of us to have.

Bill [Sutton] is now almost dramatically among the resisters and by the [same] token – one would sense – in something of a crisis. Some of his own protégées now do you homage… He can’t, he won’t see. (20 October 1959) 14

The two reviews sent by O’Reilly were by J.N.K. (Nelson Kenny) in The Press and Toss Woollaston in the Star; both were highly complimentary. Kenny’s review spoke of ‘an extraordinary creative outburst’ resulting in works that avoided conventional ‘elegance, refinement or beauty’, ‘with no incidental decorative qualities’, and which ‘don’t look like the paintings of anyone else, here or abroad’. Here, slightly abbreviated, is the review:

Colin McCahon’s exhibition of recent paintings and drawings at Gallery 91 is no less remarkable than his illuminations of John Caselberg’s poem, “The Wake”, which were shown in the city earlier this year. It is a very large exhibition easily filling all the wall space in the gallery, although it consists entirely of works done between November 1958 and August this year. Although it may not take Mr McCahon very long to put the paint on this is still an extraordinary creative outburst…

Anyone who equates art with elegance, refinement or beauty in the conventional sense of the word may be repelled by these works at first and anyone whose experience does not include contact with the New Zealand landscape in its more powerful manifestations may have no affinity with them.

Formally, the works of this exhibition show a reversion to the big emotional forms of Mr McCahon’s early religious painting. But his preoccupation with space in recent years has resulted in more sophisticated handling of these forms. Whereas once they jostled each other now he uses space to create taut relationships between them…

There is, however, very little sensuous appeal in these works; there are no incidental decorative qualities in them which can be easily admired and they don’t look like the paintings of anyone else, here or abroad – although there are affinities with some American painting. Anyone going to see them must expect more than to have the eye titillated…Colin McCahon is one of the very few painters in this country who is also an artist.15

In the Star, Woollaston’s review, headed ‘Man’s Predicament in his Own Word [sic for World]’, was equally admiring; he emphasised the existential and ‘tragic’ gravity of the paintings, the implicit presence of the Crucifixion, and the pervasive presence of words used ‘frankly and without apology’; he mentioned also ‘the complexity of relations between relatively simple shapes’, and the sense of a painter trying to discover new rules, ‘to see whether they will work for him and so for us’; slightly shortened the review reads:

The subject of these paintings is, most of all, the predicament of man in his own world, culminating in the Crucifixion. The Crucifixion is implicit in every picture here, whether by words, by light piercing the darkness, by the visible strain of suffering, or by something as hard to describe as an atmosphere.

So they are necessarily tragic paintings, and, as such, rightly make no overtures to the public, no effort to be charming or appealing. It would be an unpardonable abuse of their trust if they did that deliberately.

Other subjects beside the Crucifixion are present in them—for instance particularly in the Northland series, landscape…

The written word, too, most often quoted from the Bible, is frankly and without apology used as a subject for painting. No one seeing this exhibition can dismiss those pictures in which lettering is painted, without missing the very unity and power of the artist’s whole work…

It is obvious that part of the painter’s work here is to discover rules and try them, test them as he goes along, to see whether they will work for him and so for us. When a whole sky cries “Elias” as in No. 25 [Elias, 1959] who shall say lettering should not be big in a picture. Or who object to it when a glimmering whisper of time is given in the darkness of a passing river? (No. 18) [Tomorrow will be the same but not as this is]

… Above all, they move us through the complexity of the relations between relatively simple shapes and colours whether these are of sky, earth, written words, the wooden cross, or extra mundane shapes like the shaft of doom in No. 18, or the song-burst of a tui made visible up in the sky of one of the Northland panels called “Tui”.16

O’Reilly mentioned Woollaston’s review to McCahon with strong approval of its freedom from egotism and artistic rivalry:

Toss’ contribution we feel most grateful for and hope you will too. He seems (as [Rudi]Gopas says) to feel secure enough now in his own approach not to be disturbed at the approach of others and so no longer a prey to jealousy and other egotistic emotions tied up with. He is quite humbled too by the superiority of your energy and output. This alone should humble all of us who jabber on the sidelines. (20 October 1959). 17

In the same letter he also mentioned Doris Lusk’s speech at the opening:

Doris’ talk at the opening (wholly about the sort of chap you were through

her acquaintance with you) which she gave with an obvious sense of her inadequacy to the task before her, was, apart from the work itself, the most moving thing that happened about here. It is a pity it was not recorded: it does not exist either in written form.18

McCahon’s reply was full of gratitude and relief:

Many thanks for yours and the enclosures – the first word I’d had about the show. Your reviews arrived on the same day as the newspaper room’s Chch papers. They are incredibly slow…

From your letter & one Hamish [Keith]19 got too it does seem that this show has not passed unnoticed in Chch. I was not at all surprised to hear of Bill [Sutton’s] difficulty. After all we do paint in utterly different ways & I must say that I find the post ‘Norwester in the Cemetery’ paintings very hard to understand & take – as in the Group Show one.…20

The news of Doris [Lusk] doing the opening talk was quite new to me. I think I have been extra well-supported by my friends in this show.

The Toss contribution amazed me. It was a most generous thing to do & is well written & to the point. Not in the least the usual catalogue of information that mostly passes for an art review here… (27 October 1959)21

McCahon wrote to Lusk thanking her and offering a painting; she replied:

As for “opening” your show it was a pleasure to do so, and if I made a good job of it, the reason is the sincere & deep admiration I have for both you and your painting, and the words came easily, though I made no attempt to explain you! Toss certainly made a job of that. Since you have offered me a painting, may I have one of the warm little “Elias” ones. Apart from some of the very large compositions I like those the best…22

McCahon also expressed gratitude directly to Woollaston and offered to give him the homage painting, Toss in Greymouth. He emphasized his concern with ‘communication’ and whether or not he had achieved it:

A mere note to thank you for the review which arrived last week sent up by Ron. I was greatly moved & pleased. I was very anxious about those paintings whether people would see what I wanted them to. Here with some viewers I felt the communication was too difficult & didn’t come across & I find I can’t honestly tell myself now whether or not this communication is made…

Should you like to have the ‘Greymouth’ from the show – please let André know & pick it up some time.But please don’t feel you must accept it if you’d be happier without. (27 October 1959)23

Before leaving the topic of the Gallery 91 exhibition it is instructive to look at Tomorrow in the context of some other paintings in the ‘miscellaneous’ group. The horizontal banding which is such a feature of Tomorrow is present to some extent in most other paintings of the group, notably Black white French Bay, Black, white and orange landscape, Black and grey landscape and others. The degree of ‘realism’ and ‘abstraction’ in these works varies, but probably all are in origin at some level French Bay landscapes with the banding related to cloud, sky, hills, water, land, in various combinations and degrees of abstraction, sometimes with a contrasting element (vertical, diagonal, square etc.) included to vary the composition. Tomorrow manifests all of these elements, with its four horizontal bands, easily read as sky, hills, water, land, plus a diagonal intrusion and a prominent title. Is it also, at one level, a French Bay landscape? Possibly. If so, the grey band often read as a river is more likely to be a tidal channel24; not that it matters especially – as the title suggests that ‘realism’ is not the primary intention. It is also revealing to compare Tomorrow with two other works in the ‘miscellaneous’ group whose titles also point towards symbolism: Cross (1959, AAG) and A landscape – Fragments of a Cross (1959, pc).

A comparison between these three paintings offers in particular a persuasive explanation of the mysterious diagonal intruding from the upper left corner of Tomorrow, suggesting that it, too, is a ‘fragment of a cross’– a diagonal portion of the same saltire cross which is complete in Cross and in the process of fragmenting in A landscape – Fragments of a Cross. As for the ‘meaning’ of this symbolism, different viewers will have their own explanations, but it may be helpful to recall Woollaston’s remarks: ‘The subject of these paintings is, most of all, the predicament of man in his own world, culminating in the Crucifixion. The Crucifixion is implicit in every picture here, whether by words, by light piercing the darkness, by the visible strain of suffering, or by something as hard to describe as an atmosphere. So they are necessarily tragic paintings…’

The memorable and unusually long title contributes further to understanding. McCahon’s phrase ‘Tomorrow will be the same but not as this is’ has the enigmatic eloquence of a Buddhist koan. The idea of perpetual recurrence is one that interested him. Back in 1949 he wrote to O’Reilly: ‘But it[’]s awful to know that what has happened before will happen again[;] the landscape turns & rends you,25. And, in a 1981 letter to Peter McLeavey he quoted himself when writing about making recent contact with a teacher who had taught him in primary school; reflecting on the experience he referred to the 1959 painting: ‘Strange how time works – me in Standard 1 and she really not much older than I was, but I not so well informed. Well, what now. Time closes in on us all and the reality of a life span is more real than it was a few years back. Tomorrow will be the same but not as this is.’26 There is something, too, of Heraclitus’ statement as recorded by Plato: ‘Heraclitus, I believe, says that all things pass and nothing stays, and comparing existing things to the flow of a river, he says you could not step twice into the same river’ (Plato: Cratylus 402a = A6). Others put a different reading on the metaphor of time as a river. ‘Heraclitus believes in flux, but not as destructive of constancy; rather it is, paradoxically, a necessary condition of constancy, at least in some cases (and arguably in all).’27 Whatever precisely McCahon intended, his title adds to the mystery and magic of the painting, as well as supplying another horizontal element to its structure.

II Campaigning for Tomorrow

The first reference to the idea of a public subscription for Tomorrow was reported by O’Reilly while the show was still running:

André [Brooke] started a fund on Friday night (that then reached £4.10) and a few of us decided that the big ‘river’ landscape (“the same but not as this is”) was what the McDougall really ought to have and that’s what the fund is for. I shall suggest to André that, after his regulars have had the chance to see and contribute I bring it here to the library for a while; and we may get it up where the mural should go.28 (20 October 1959)

The ‘few of us’ who were original contributors to the fund included: Olivia Spencer Bower, Frank Gross, Mr & Mrs Selwyn Hamblett, Doris Lusk, John Summers, Leo Bensemann, Ron O’Reilly and David Langley. Spencer Bower, Gross, Lusk and Bensemann were all fellow painters and Group members; the others were Christchurch friends, relatives, supporters and collectors.

O’Reilly evidently wrote to Charles Brasch seeking a contribution to the fund and received a stinging rebuke in reply, in which Brach accused him of ‘hasty judgment’ and of being both unwise and ‘rather irresponsible’ in selecting a work for museum acquisition so soon after its making, and before its quality had been adequately assessed; the letter is slightly abridged:

I quite agree with you that one has to get to know Colin’s work well before understanding it and deciding whether it is successful or not and assessing its merits relative to his other work. As you know Colin himself often exhibits paintings in order to see how they will stand up in a gallery, and sometimes decides in the end that they don’t. So I was dismayed to learn that you had made the hasty judgment that some of his recent work shown at Gallery 91 was so good it deserved to be hung in the McDougall, as the first work (I gather) to represent him there. I am not prepared to pass final judgment yet on any of this work, as you appear to have done. I am certainly not convinced yet that it is among Colin’s best: I am convinced that only his best should represent him in a public art gallery. I am inclined to think that in none of the larger works in this recent show has Colin fully worked out the possibilities and implications of this phase of his painting, so that I want to wait and see what he does next – that is I want to see the whole output of this phase, once he has finished with it and gone on to another; only then I think will it be possible to decide which are the best works of the phase and which of them, if any, are good enough to represent him in a public gallery…

I don’t think you have been wise in choosing one of these recent works for the McDougall so soon, and I do not support you. It may turn out that there are better works in this phase than the one you have chosen. It may turn out that, relatively, this is not even one of the successful ones. I don’t believe that anyone can tell yet. I think you may be doing Colin harm in buying for the McDougall a work that you can’t yet be sure about. It would be much wiser to wait; it would be fairer both to Colin and the McDougall. To be plain, your rushing in like this seems to me to be rather irresponsible, and not the best way of persuading people that Colin’s work is important. (7 November 1959)29

Brasch knew McCahon’s work as well as anyone and had been a dedicated supporter and collector for 15 years, but he was always slow to recognise the merit of change and innovation in his work, as McCahon was aware, especially as it moved towards abstraction and the use of text in the later 1950s.30 His first preference was always for Colin’s landscapes especially those panoramic paintings of Otago Peninsula in the 1940s he first responded to and which became for him a kind of touchstone.31 For example, initially, he disliked the religious paintings though gradually modified his views over time and came to admire paintings he had initially disliked, a case in point being Crucifixion with lamp (1947) which at first he derided as ‘repulsive’ and later purchased for his collection.32 The caution and conservatism of his responses is fully on display in this letter, his being unwilling to concede any merit to Tomorrow or indeed to any work in the 1959 exhibition. There was possibly also an element of unconscious rivalry between himself and O’Reilly as to who was McCahon’s ‘best’ supporter.

O’Reilly in reply accepted that his approach may have been somewhat precipitate but strongly rejected the accusation of irresponsibility and reaffirmed his belief in the quality of Tomorrow; he reminded Brasch that he had some form in early identifying key works by McCahon, as in his recognition of the importance of On building bridges: triptych in 1952 – a work which Brasch had been critical of.33 He wrote:

I realise now that it was presumptuous of me to have written to you as I did and should have been suitably abashed had you rebuked me for say rushing into a decision about a matter on which you preferred to suspend judgment; but I shall not be called irresponsible because my mind does not work as yours. I have no doubt about the stature of “Tomorrow will be the same…” any more than I had of “On building bridges” when I exhibited that work here – which led directly to Westbrook’s asking to meet Colin and – on the same morning – inviting him to work for him in Auckland. (10 November 1959)34

In recognising that his ‘mind does not work as yours’, O’Reilly offers a partial explanation for the difference between himself and Brasch as supporters and collectors of McCahon. O’Reilly was much more open to McCahon’s experiments and radical evolution as a painter. This difference is clear in the contrast between their collections: Brasch’s was largely confined to the 1940s and early 1950s, whereas O’Reilly’s started in the late 1930s and he continued to add to it regularly to the end of McCahon’s career, embracing each of the painter’s changes and developments as they occurred.

O’Reilly let McCahon know about his contretemps with Brasch:

Biggest blow in our present presentation effort is [that] Charles has snubbed us. He has come to believe that certain of your earlier works (all in private hands) should be in public galleries, but only reached such conclusions very slowly. Moreover (he says) you yourself have come to the conclusion that certain of your works are not good enough. He is therefore appalled at our precipitancy in campaigning for the McDougall to acquire one of these very recent works and has told me he regards my part in it as “irresponsible”.

I find this v. hard to take though I acknowledge that I left myself open to a rebuff by writing what could be regarded as importunately to him – knowing that he had – with evident deliberation – not made any comment on the ‘91’ exhibition (and this on top of some expressed scepticism concerning the value of “The Wake” panels and what Daphne – and Toss “imagined they saw in them”.) I am very sorry for the ineptitude I have shown recently in the handling of these matters.

But of the value of “Tomorrow will be the same…” I have not the smallest

doubt; and shall campaign for it as hard and as well as I can. It is really magnificent. (13 December 1959)35

O’Reilly deferred but did not drop the subscription idea. He wrote next in May 1960:

I still have your Tomorrow will be the same… in the library waiting to see what the City’s new picture selection procedures will be. Because it could prejudice Council’s freedom of action I was asked not to solicit subscriptions any more in the library; but I have had the work framed (which works the magic for many people) and hung in the N.Z. room meantime. We should soon know whether there is a chance of getting it accepted or none at all. In the meantime it looks magnificent where it is. (18 May 1960)36

At this point there is a brief gap in the record concerning Tomorrow. At some point a decision was made to include the work in McCahon’s 1962 (The Gate Series) exhibition at the CSA Gallery in Christchurch so as to resuscitate the subscription plan. But before the 1962 exhibition, a situation occurred in 1960-61 which had a significant bearing on the outcome of the Tomorrow subscription.

In 1960 the first Hay’s Art Competition was held in Christchurch attracting over 400 entries, but the three judges (Russell Clark, Professor John Simpson and Peter Tomory) could not agree and each chose a different winner. Clark and Simpson were academics at the Canterbury University Art School at Ilam and Tomory was director of ACAG.37 The work chosen by Tomory was McCahon’s Painting (1958), a radically abstract work painted in March 1958, just prior to his trip to the USA. The McCahon work immediately aroused controversy with a wide gulf between supporters and detractors as played out especially in newspaper correspondence columns. McCahon was so depressed by the newspaper furore that he threatened to leave the country (as he told Brasch): ‘Thanks for your earlier letter on the Hays affair. The [Otago Daily Times] was the only paper to be at all sympathetic. I have about 100 quite devastating cuttings from all over N.Z. which I am keeping for when I eventually manage to leave N.Z. for good – to remind me in times of homesickness of what to expect should I return. (The Auckland Star reproduced the picture on its side.)38’ Brasch in reply was kindly and reassuring: ‘Do let me beg you not to take newspaper criticism so much to heart. It’s worthless, nearly all of it, as you know. I agree it’s infinitely depressing to read, and hurtful when you’re consistently misunderstood, misrepresented, sneered at’.39

A judicious and balanced comment on Painting (1958) was offered by the Press reviewer Nelson Kenny:

Colin McCahon’s winning entry is not one of his best paintings; it is not nearly as moving as his Northland Panels, “The Wake” panels or several others shown in his one-man show in Christchurch last year. Nevertheless, it is a good painting, possessing uncompromising strength and intensity. A newspaper reproduction cannot do any justice to the subtle tonal modulations and contrasts which are the source of its expressiveness…It needs to be looked at for a long time before it yields its secrets. It is a contemplative painting which needs contemplating upon. Above all, its title should be noted – “Painting”. It is not a picture of anything. It is not meant to be anything but what it is. It is simply a surface covered with paint of different tones and colours – as ultimately is any painting – and it must be looked at with this in mind if its stark austerity is to be appreciated.40

This purely formalist reading is probably less fully attuned to McCahon’s intention than that of Woollaston who wrote a piece about Painting for The Press after a flood of letters – many of them ignorantly negative – in the correspondence columns. After a close formalist reading in his opening paragraphs, Woollaston changed tack in his closing comments:

I would say that, if the picture has a subject, a “meaning” as people like to say, it would be of such a kind as to make necessary the extreme abstinence from representation that we find in it. It is too close to the unutterable for easy verbal communication: its subject is too disconcerting to allow many people to indulge in the easy response of “I like it”, which unfortunately is all that most people will allow of themselves for painting.

It subject could have to do with the sharp singularity of the self against the blurring of universality; or the hope of light against the thrust of darkness; or the anxiety of being against the dissolution of not-being.

Whatever it is, it was not painted in words: and these words I am offering are intended only as suggestions, in the hope that they may perhaps, help someone to look at the painting and experience it for himself. I do not pretend to have exhausted all that it offers, either technically or imaginatively.41

All three prize winners were offered to the McDougall Gallery by Hays Ltd., and the purchase of the McCahon was recommended by the majority of the Arts Advisory Committee of the City Council (which processed all acquisitions to the Gallery); but on the recommendation of the McDougall Director, William S. Baverstock – a notorious reactionary and enemy of modernism – all three were rejected by the full Council, Baverstock arguing that that such a gift was wrong in principle. In reality Baverstock’s appeal to principle was a way of disguising his hostility to McCahon’s painting (‘not art but the negation of art’, he is reported to have said) and his determination to keep it out of the gallery.

The Council’s decision led to a controversy in The Press about Art Gallery Policy; with letters from Leo Bensemann, Doris Lusk, M.T. Woollaston, W.A. Sutton, E.N. Bracey, John Coley and John Summers all attacking the Council decision, though other letters supported it. Summers’ letter, for example, said:

Whatever may be the rights or wrongs of the City Council’s rejection of all three paintings offered by Hays, Ltd. to the McDougall Gallery, I consider it a grave anomaly that the work of our most powerful painter is not represented there: neither any of his earlier landscapes, his rightly disturbing religious paintings, nor the later and often symbolical abstracts which remind us that in our times we are living on a volcano. I suggest that a retrospective exhibition of McCahon’s paintings would be stimulating, to say the least, and could, in its variety, provide bridges for the understanding between his more easily accepted and the more difficult work and could provide the gallery with a range of work from which a painting could be chosen… 42

There was even an editorial in The Press about the controversy which deplored the rejection of Painting:

Whether the controversial “Painting” by Colin McCahon is a great work of art is apparently arguable: but it would be a significant addition to the gallery’s stocks, if only as an example of what New Zealanders of the mid-twentieth century argued about. Further, because of Mr McCahon’s standing, it is safe to assume that in not very many years the painting will be worth more than the artist received as his share of the prize.43

The Council’s rejection no doubt increased the determination of O’Reilly, Summers and co. to find an alternative way of getting a work by McCahon into the McDougall Gallery. Hence the revival of the subscription scheme in 1962. 44

The last entry in the typewritten catalogue for The Gate Series (assembled by O’Reilly from information provided by McCahon) read:

46. Tomorrow will be the same but not as this is 1958/9, 65 gns. (Subscription Picture. Friends of the artist are seeking subscriptions to acquire no. 46 for the City. The price is 65 gns of which some 10 gns has already been received. Subscriptions may be left with the Secretary or with Mr R. N. O’Reilly, care of Canterbury Public Library.)45

O’Reilly wrote to McCahon in November to report on progress:

As you will see from the enclosed we have negotiated our first hurdle.46 The next will be the meeting of the Council’s A[rt] G[allery] Committee on Tuesday afternoon next, 4th December, but we may not know how that goes until we get to the final one, the Council meeting of Monday, 17 December.

Greetings

Ron

Attached:

- Letter to Colin McCahon enclosing cheque for £73.15

- List of subscribers

3) Letter to W. Baverstock from John Summers and R.N. O’Reilly on behalf of the subscribers.(30 November 1962)47

Subscribers, apart from the ‘originals’ mentioned earlier, included many painters: Russell Clark, Philip Trusttum, Rudolf Gopas, John Oakley, Toss Woollaston, Maurice Askew, Quentin McFarlane, Rhona Fleming, Bill Sutton, Ivy Fife, Louise Lewis, plus various academics, lawyers, architects, publishers, librarians and others. There were 64 subscribers in all.

McCahon replied to O’Reilly’s letter of 3 December:

The cheque arrived this morning. Herewith the receipt.48 And thanks to both you & John Summers for all your efforts. I only hope that the city fathers etc won’t be too difficult. I suspect that they might be, there’s not much allowed to pass in that direction. (3 December 1962)49

In The Press for 18 December 1962 there is a detailed account of the Council meeting referred to in O’Reilly’s letter. It quotes William Baverstock’s reluctant report:

I am well aware that the fact that I do not like the painting and cannot enter into the spirit of the interpretation of it should not restrict my judgment as an art gallery director. I have often taken action beyond the scope of my personal likes and dislikes. I agree, moreover that a collection of New Zealand art of today is not complete without some example of the work of Colin McCahon.50

Baverstock objected, however, on principle to subscriptions being raised for art works as a method of building a public collection. Nevertheless he did grudgingly recommend the work for adoption by the Council for the Gallery. Cr. Stillwell objected, describing the painting as ‘a figurative monstrosity which should not be hung in our beautiful art gallery’; he also objected to the fact that ‘it is only on hardboard, not even on canvas’.51 His amendment that the council decline to accept the painting, seconded by Cr Mabel Howard, M.P. was defeated on voices. The Press story also quoted these paragraphs from O’Reilly’s and Summers’s letter about the painting:

‘You will be aware of the importance of McCahon in the development of New Zealand art. We hope that you will also agree that this picture is a good one, and a suitable work with which to represent him in the Gallery’s collection.

‘It depicts a powerfully flowing river (or tidal reach) under a steep scrub-covered hillside and a sky of lightly moving clouds. The heavy expanse of beach, the grey water, the rising land and the sky form parallel horizontal bands contrasted in tone and in breadth. Their apparently simple, rectangular shapes are harmoniously proportioned and subtly varied where they meet. For example, a drag of a brush stroke suggests a strip of foam by the water’s edge; another a wisp of mist over the hill-top. The colour again is apparently simple to the point of austerity (a modulation of greys between black and white) but a hint of blue in the sky suggests that the world of chromatic splendour might not be far away.

‘The strong diagonal line in the upper left of the picture, like a pointer thrust out of the sky, introduces a disturbing note into an otherwise peaceful composition. The artist has reinforced the disquiet, but not effaced the underlying serenity, by the words he has scrawled across the bottom. What he means we are not told. It could be that we are simply asked to look afresh at this lovely, lonely, wild neglected land of ours. But we shall however not easily exhaust the meaning of the picture, nor will some of us soon cease to be haunted by it.’ 52(The Press, 18 December 1962)

And so Tomorrow will be the same but not as this is finally entered the Robert McDougall Art Gallery, joining there Frances Hodgkins’ Pleasure Garden (1932) which had similarly entered the Gallery in 1951 from public subscriptions and a comparable tussle with reactionary administrators and local body politicians. Tomorrow became not only the first McCahon in the McDougall but one of the first in the country in a public gallery collection, preceded only by Abstract (1952), donated to the Suter by John Caselberg in 1955 and three works in Auckland City Art Gallery: On building bridges: triptych (1952), and Takaka: night and day (1948) acquired in 1958 and The Marys at the Tomb (1950) in 1960.53

About the Author

Peter Simpson has been researching and writing about Colin McCahon for more than thirty years. He has curated exhibitions of McCahon’s work at Auckland Art Gallery, Lopdell House, Titirangi, New Zealand Portrait Gallery, and Hocken Collections. He has published numerous articles on McCahon and given lectures and talks about his work in Australia, Asia, Europe, America and throughout New Zealand.

His books about McCahon include Answering Hark: McCahon/ Caselberg Painter/Poet (Potton Books 2001), Colin McCahon The Titirangi Years 1953-59 ( AUP, 2007), Patron and Painter: Charles Brasch & Colin McCahon (Hocken Library, 2009), Bloomsbury South: The Arts in Christchurch 1933-53 (AUP, 2016), Colin McCahon: There is Only One Direction (AUP, 2019), Colin McCahon: Is This the Promised Land? (AUP, 2020), and Dear Colin Dear Ron: Selected Letters of Colin McCahon and Ron O’Reilly (Te Papa Press, 2024).

Peter was a foundation member of the McCahon House Trust and is a member of the McCahon Research Committee for the McCahon Trust.