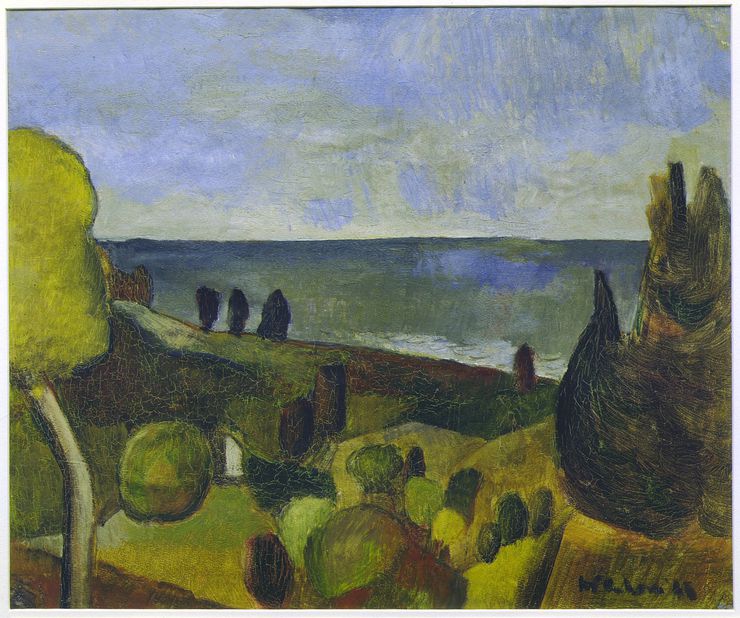

Ruby Bay

Colin McCahon, Ruby Bay, 1945, oil on paper, 394 x 473mm. Collection of Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellingto, courtesy McCahon Research and Publication Trust.

Lakiloko Keakea, Fafetu, 2018. Installation shot from Objectspace, November 2018. Lakiloko Keakea is a member of Fafine Niutao I Aotearoa. Image by Sam Hartnett.

Zoe Black

I spent a summer holiday around the South Island a few years ago. My husband and I had a campervan and for three weeks we trekked across hills and countryside, stopping at small towns and beaches as we made our way up the west coast, across and around to Ōtautahi Christchurch. On New Year’s Eve we happened to be at Ruby Bay, just outside Nelson. Friends were in the area and, although the population swells at that time of year, we managed to find a quiet campsite on the shoreline of the idyllic bay.

It was a quaint spot to celebrate the auspicious occasion. We lit a campfire, ate seafood and marvelled at the charming way the land seemed to protectively wrap around the beach and, as night fell, Ruby Bay lived up to its name with a dramatic crimson sunset.

That particular area at the top of Te Wai Pounamu has prompted an emotive response in many artists who have spent time in and around the district. The lazy roll of the mountain ranges stretching across the horizon, the scrubby fields and the contrasting bolts of blue in the sky and the sea have been captured on canvas for decades. Toss Woollaston and Colin McCahon have done so most famously, both of whom continuously returned to the hills overlooking Tasman Bay.

This work from 1945 uses that elevated vantage point to record McCahon’s feel for the little stretch of coastline. Now, it reads as a somewhat simple painting, far less assuming than others in his oeuvre, yet the pared back abstracted forms were daring for the time in regional New Zealand. We can see McCahon feeling out a new way of working with paint and shape, but still accurately capturing the sleepy seaside. At this time, when he was only 24, he was starting to find his way to interpret the land, still looking to formal ways of working but taking on the ideas coming from overseas that sought something more than just realistic depiction. Playing off new concepts mulled over with friends, dramatic forms of moody browns, muted yellows, and deep greens became his preferred vocabulary as he found his voice to illustrate the whenua.

In my role at Objectspace I work with artists and communities who are creating artworks that also reflect their place in Aotearoa New Zealand. For most, here is their second or sometimes third home. These artists are making objects referencing what has come before, but they are also embracing new materials, colours and forms to create in ways that interpret these discrepant surroundings and show how their making has inescapably changed as they have settled into their new environment. Many are women who work collectively, at home or in community spaces. Creating together means learning from each other and problem solving as a group to try out different things. Much of the investigation comes from necessity, as access to materials that they are used to working with is difficult. For example, the woman’s collective from Tuvalu, who we have been working with to realise a few projects, utilise recycled plastics and bright acrylic wool in some of their making as a substitute for pandanus leaves, as pandanus aren’t able to be cultivated here. These new materials are delicately stitched and woven into the most beautiful things, carefully upholding tradition but also infusing personal interpretation and innovation.

It is this way of creating - respecting the past while moving ahead into the new - that echoes throughout art making in New Zealand. We have a history of working quietly together to progress and create artworks that more accurately defines our unique place in the world, while responding to the global currents that ebb and flow around us. Exhibition and notoriety is not always the end goal, it is about making because making is an intrinsic and undeniable part of life, using what is on hand, transforming humble materials to articulate a viewpoint and create something powerful, honest and appropriately beautiful.