Keep New Zealand Green

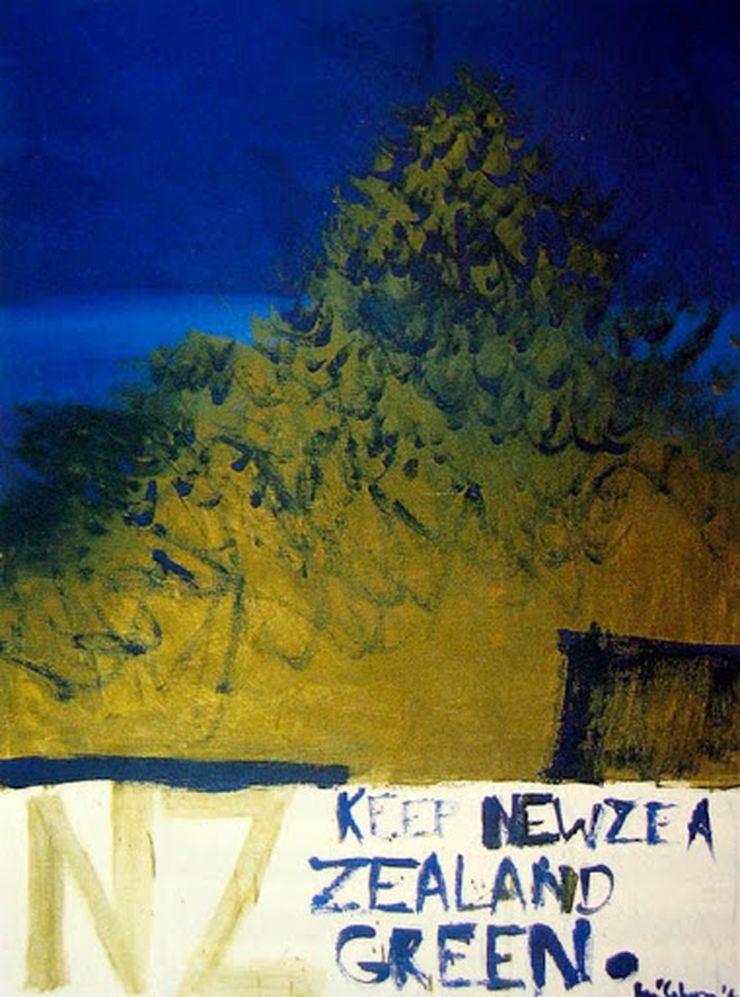

Keep New Zealand Green, 1966, oil on canvas, 1015 x 755 mm. Private collection, image courtesy McCahon Research and Publications Trust.

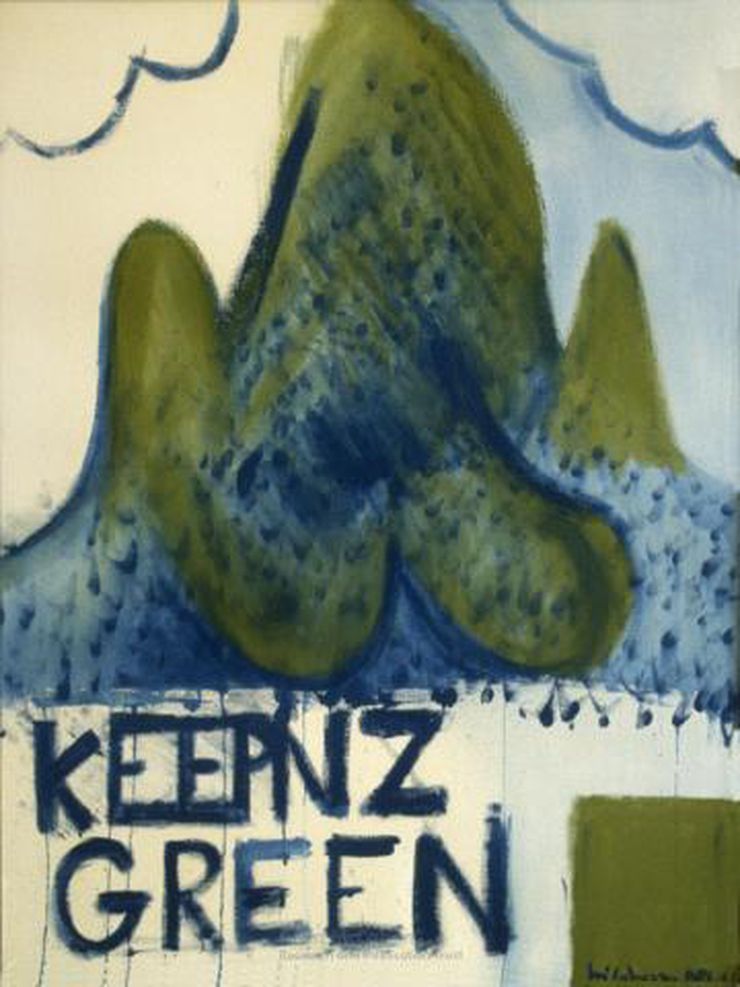

Keep New Zealand Green, 1966, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 1001 x 748 mm. Private collection, image courtesy McCahon Research and Publications Trust.

Tessa Laird

I wonder what Colin McCahon had in mind when he painted Keep New Zealand Green? (see top left). It wasn’t the only time he painted this phrase. I was drawn to this work because I appreciate McCahon’s nascent environmentalism. 1966 seems to be well ahead of the game to be thinking about what was then called 'conservation'. Nevertheless I’m curious – just what shade of green was McCahon hoping to conserve? Was it the wild, dappled melange of native bush greens, from olive, to lime, to darkest emerald? Or was it the uniform Brunswick green of pine plantations? Or was it the rolling khaki hillsides he so often eulogised in paint? I suspect the latter, which means that for McCahon, keeping NZ 'green' meant keeping it shorn and sheep-ready, the better, one imagines, to appreciate its curves.

I’ve chosen this work because it’s more bushy than the other versions with the same title. And yes, all these double entendres are deliberate. In Feminism and the Mastery of Nature, Val Plumwood catalogued the many ways in which Western philosophy has lumped women (as well as non-Europeans) into the same category as nature and the land, which might not be so bad if nature wasn’t also in the category of 'that which is to be tamed and exploited'. Landscape, according to the colonial doctrine, is just there to be fucked, one way or the other.1 Indeed, there is one version of Keep New Zealand Green which features mountains as boobs, or is it a backside, or even, balls? (see bottom left).

The version I've chosen is different from McCahon's usually denuded landmasses.It features a tufty stack, pile, or heap of scumbled green. It’s about as Woolaston as McCahon gets. Is it a tōtara, or is it a Wookiee? I like to imagine it’s actually a close up of some of Northland’s finest sticky buds. There is no way McCahon could have been an artist in the 1960s and not partaken of the Electric Pūhā. Perhaps this is what he meant by 'Keep New Zealand Green?'2

In the more than 50 years since this work was painted, the colour green has gone through a radical politicisation and depoliticisation. Globally, green parties have, like seeds, sprouted, grown, and in some cases, withered and died. Frustratingly, for those who believe in genuine ecological thought, the colour green has also been radically co-opted by capitalism, in what’s now known as 'green washing' – selling products and services to those who want to feel that their unsustainable lifestyles aren’t killing the planet (mea culpa, BTW).

One of my favourite books of the last few years is a collection of essays called Prismatic Ecology: Eco-theory beyond Green. It aims to expand ecological thought beyond its long hangover from Western European romanticism with its dark forests and sublime, unknowable wildernesses. Prismatic Ecology brings other entities into the conversation, and not just mountains, deserts, seas and skies, but the cities, plastics and pollution that are a very real part of our ecologies, whether we like it or not. The chapter Greener by Vin Nardizzi takes its name from a 1947 pulp sci-fi novel, Greener than you think, by Ward Moore. It’s about the lawn that ate Los Angeles – and then the world! It’s a classic example of post-war invasion paranoia, not to mention the-coloniser-afraid-of-being-colonised trope. Such fears reach their apogee of expression in this tale of the suburban white dream of the well-kept lawn running rampant and out of control. Which is pretty much the definition of the Anthropocene anyway: the mid-20th Century 'Great Acceleration' burning fossil fuels and destroying worlds everywhere. Even something as seemingly innocuous as a garden lawn can eat up ridiculous amounts of fertilisers and pesticides. In the US, 75% of household water is used on lawns,3 and Aotearoa, for all its extant beauty, has suffered from the imposition of Pākehā 'lawn order' (Nardizzi’s pun).

I once heard Lisa Reihana utter the heretical phrase (at least to farmers), that sheep are like maggots on the landscape. Certainly, Bruce Pascoe has argued in his book Dark Emu that sheep changed the ecology of Australia forever, in ways which make it all the more vulnerable to bushfires, and sorry to say, far less green. Then again, Philip Armstrong wrote a whole book about sheep and our unfair attitudes towards them. They are the environmentalist’s scapegoat, so to speak, when really it was (white) humans who put them there in the first place. Perhaps Reihana was being polite, or metaphorical, when she called the maggot-like white creatures swarming over the landscape of Aotearoa 'sheep'?

Either way, I haven’t been able to look at New Zealand’s countryside the same way since. Every hill, every rolling field, seems to be utterly naked, stripped bare, each tree like a hair uprooted from its follicle, with the plucked surface still smarting from its depilation. Long before I read Plumwood, I started to feel that the deforestation of the planet was spurred on by the same patriarchal construct that required women to depilate their bodies. The wild and unkempt bush had to be tamed, whether on the bodily, national, or planetary scale. In my final year of Elam undergrad in 1993, I staged a performance at lunch time in Vulcan Lane. Dressed as a rugby player, blindfolded and gagged, I had my legs waxed by two men in French maid uniforms.4 The title? Deforestation of the Amazon. For years, I’ve thought of that work as an embarrassing piece of juvenilia. But I could never have imagined back then that in 2020 Brazil would have a president who makes rape jokes and sees First Nations people as nothing more than an annoying hindrance to further exploitation of the forest.5 I could never have imagined a pussy-grabbing President of the United States who turns National Parks into rubbish dumps. Or an Australia in non-stop flames whose Prime Minister tells people to pray. And I could never have imagined, after all my campaigning for female hairy legs in the 1990s, that we would be living in a new era of compulsory pubic baldness for young women. Somehow, these things seem connected. If we can’t love our own bushes, how can we love and nurture luxurious growth in nature?

I like the bushiness of this painting by McCahon, the directness of its message and its economic form. It reminds me of simpler times. Not 1966, I wasn’t around then. But I used to see McCahon walking around Grey Lynn when I was a young teen in the 80s. And later, when I was at Elam, I met someone who was flatting in McCahon’s old house, years after the painter had died. My friend held a party there, and I went dressed as a male beatnik, with a turtleneck, beads, beret, and stuck-on felt sideburns and goatee. I was going through a bit of a cross-dressing phase at the time, including very bad Elvis impersonations. In my red-wine addled state, I was sure one of McCahon’s final, unfinished paintings, still on its easel and visible through the window of his old garden studio, said 'Elvis' (it was, of course, Elias).

I definitely had too much to drink that night. At some point, playing the beatnik to the hilt, I read out some poetry, and demanded a minute’s silence for McCahon. I don’t think anyone complied. I also helped myself to a book of Artaud’s collected writings (later returned), and then stumbled home, vomiting in some bushes (see, they are useful). I should have laid off the wine and just stuck with the green stuff.

Writing this almost twenty-five years later, from across the ditch, I’m keenly aware that it is often those New Zealanders who are away from home that are most eager to protect its clean green image, hence the Green Party doing so well in special votes. But the reality is that our agricultural industries are polluting our rivers and belching out carbon. Then again, after a summer of drought, smoke and fires, Australia has barely any bush left at all. The grass in Aotearoa is still, admittedly, several shades greener. Let’s try to keep it that way, eh?

[1] Which might be one of the reasons Indigenous scholars are so sceptical of the predominantly white “Ecosexual” movement, although its founders, Beth Stephens and Annie Sprinkle, are adorable, and would only ever advocate for consensual engagement.

[2] There’s a definite stoned aesthetic in operation here: McCahon didn’t factor in the space he’d need to write the phrase, but just kept going anyway, ending up with: Keep New Zea Zealand Green.

[4] The late, much missed Martin Lark, who was my classmate, and Mark Amery. Amery told me it was participation in this event that encouraged him to give up his day job as a young lawyer and pursue the arts full time!

[5] In keeping with the interconnectedness of poisonous colonial agendas, Bolsonaro has also said he’d rather a dead son than a gay son, and that Africans asked to become slaves.