On Building Bridges

On building bridges (triptych), 1952, oil on hardboard, 1067 x 2745 mm. Collection of Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki. Courtesy McCahon Research and Publication Trust.

Colin McCahon & Ted Spring, Lounge bar Kiwi Hotel, 1970. Max Oettli, Alexander Turnbull LIbrary, Wellington 104372

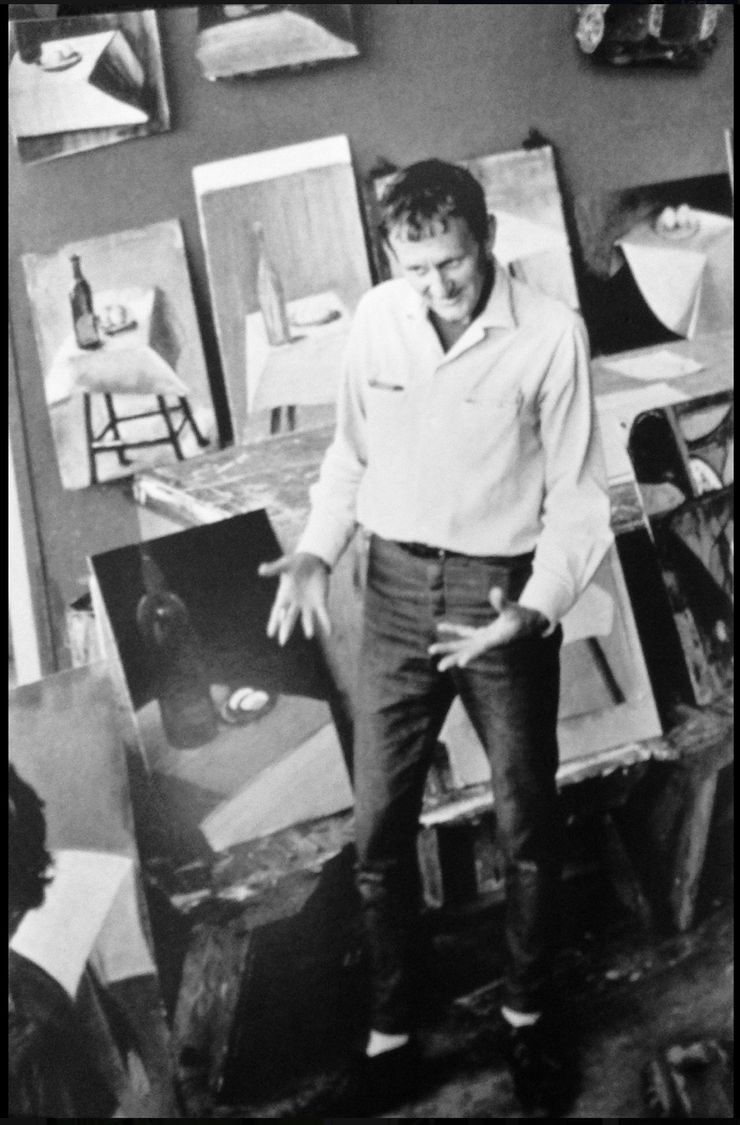

photograph by Stuart Pilkington, circa 1965

Ted Spring

The title On Building Bridges (1952) is appropriate and prophetic for both Colin McCahon and myself. For McCahon it is the work that projected him into a new life in Auckland. On Building Bridges (OBB) was one of the last works he produced in the South Island, focusing his grasp on a new technique that gelled after his Melbourne trip. I suspect it also focused a question regarding that moment in time for him. OBB initially began as a New Zealand pastoral scene, with the working title ‘Paddocks For Sheep’ but transcended such boundary fences to arguably become one of his most pivotal works.

From 1965 to ’68 I was a student at Elam School of Fine Arts where McCahon taught painting. He would ask us, his students, ‘what content can a painting hold?’ Over time OBB has revealed ever deeper layers of significance. Although McCahon’s name meant nothing to me at that time, from my first first encounter with OBB, circa 1960 at the Auckland City Art Gallery, the painting became both a sounding board and signpost marking and measuring the changes taking place in life; from shared South Island beginnings, then to the expansion of consciousness during the 1960s and now in return to these McCahon100 observances, and my proposed moving image examination of the painting’s significance.

On Building Bridges is something of an image of a post WW2 NZ lifestyle, still characterised then by earlier Twentieth-Century modalities of travel. My first sight of OBB brought instant recognition of the Canterbury Plains, as viewed from the western side windows of the Invercargill-Christchurch express train - drawn by steam locomotives and fondly known as ‘The Eckity-Peck'. The OBB triptych assembles some of the catalogue of landforms seen as the steam engine raced over the level straits on those many journeys to visit my sea captain Dad, docked in various South Island ports. Reading OBB’s subtly north aligned middle panel left/west to right/east, there is a horizontal terrace which drops into a water-cut slope, at the bottom of which is a profile of the coalescing alluvial river fan which runs to the eastern frame. In the panel to our left, there is the same geology, only south aligned. The right hand panel looks west into a close-by, water scalloped terrace. Although rivers are not seen they are alluded-to, between the lines.

On Building Bridges was painted in 1952, when the old Waitaki River shared road-and-rail bridge was still in use. The train often halted there until the bridge was clear of vehicles, then rolled grandly past a line of cars waiting for it to pass. People would wave up to the red carriages going by like they knew every one of us onboard. And we waved back. OBB also evokes for me, the Rakaia River, where the vast width of the river sees the train as a ponderous, people-filled contraption, suspended above rushing icy-blue glacier-melt braids, some able to carry all away at a stroke. As in the 1953 Tangiwhai disaster!

To my early 1960s schoolboy-eye there was more than a hint of some kind of disaster in the strangeness of OBB’s foreground structures. OBB’s style was used in International Air Race (1953) which NZ State Airline TEAL employees destroyed for packing material, a result no doubt of managements’ assessment of the painting having a ‘factual inaccuracy of the aircraft’s shapes’. If OBB’s title is taken literally, one’s reaction may also be that of TEAL’s bosses and, I have to admit that although I loved the background landscapes, my first viewings of the foreground’s ‘bridge’ structures were through TEAL-tinted lenses. Such insularity of mind and spirit all too often reared its ugliness to McCahon.

The decade of the 60s was, as is widely known, a time of sea change in NZ and in western society generally. On the strength of the appearance of my artistic talent my family moved to Auckland. Over the course of the first half of the 60s I gained a new vision and set of values, from attending Dugald Page’s art class and Russel Aitken’s English literature and geography classes at Westlake Boys High School, after Mum had bought a house almost next door to the school. I would go to see OBB quite often in that time and try my new found understandings on it, so to speak; to gauge changes. Gradually, Colin McCahon became an artist to admire. The cubistic style, with the type of brushwork and some of OBB’s colour pallet rubbed off into a small series of paintings I did, inspired by an out-of-body experience on Barry Brickell’s front porch during a ’63 Coromandel road-trip with friends. One of these paintings garnered an Auckland newspaper secondary school art exhibition award in 1964 and later elicited Colin's ‘Beauty, Beauty, Beauty’ response to seeing it in the painting room at Elam. This GM Hopkins quote from the The Leaden Echo And The Golden Echo hints that Colin held the same motivation that Hopkins elucidates, in the giving of beauty back to ‘the Giver Of Beauty and Beauty’s Self’.

Looking at OBB as being about literal bridges, now, is obvious naivety. Now is to see that McCahon stands us on the crucifixion hill of Golgotha, but the time is just after Christ’s crucifixion and transcendence, when all have gone their various ways. As previously, in his long brush-stroke draped landscapes, McCahon brings the Biblical narrative home to the familiar terrain of Aotearoa, but gone are the players. Only the set remains. What appeared to be a white, bridge-worker’s box is really the empty tomb. Rather eerily empty, as McCahon depicts the marble ossuary-like oblong as a conspicuous hollow space, excavated into the triptych’s expanse of otherwise cubistic flat picture plane using somewhat standard painterly spacial-depth means. The black uprights and diagonals are the Crucifixion’s vicious instruments. But among these grotesqueries there appears one variance, in the form of a black bridge cross-member that is not connected to the ground and that defies gravity, apparently leaving the boundaries of the picture plane at the top right of the middle panel; surely a painterly stand-in for Christ’s transcendence, rising in space above the empty tomb as per Christ’s Biblical ascension.

The dynamic of discovery for one engaged with OBB’s Canterbury setting might be as follows; you the perciever, after gazing at the background landscape, are then drawn back out, between the foreground uprights and diagonals, which in doing, so has you crossing the 'axis of action' to use film-making terminology. In other words, as ones gaze moves into and out from the landscape, through the foreground forms, one crosses the line of action established by those foreground forms. At some point one may flash that McCahon is having us cross to the other side of all the Crucifixion depictions of the last two-thousand years! You pass through the line-of-action of the three crosses and take up the point of view of looking back through them on ‘home’ terrain. The psychological effect is one of stumbling and finding Christ’s place of crucifixion in your own backyard. This was my recent experience of revisiting OBB, which came as a shock - not seeing it prior.

In the painting’s ambivalence - its quiet emptiness, its sunny state of midday moment - there is a sense that another psychological subtext seems to hang, unseen, in the space above the landscape; a monolithic ‘WHAT NOW?’ An unwritten anagram, in the lines and forms assembled there. What now for mankind? In a documentary on the making of the first nuclear explosive device, dubbed ‘the gadget’ in boffin-speak, a Manhattan team scientist recounts how those involved, after that first Trinity site detonation, asked that very question; 'what now?' 1952 saw the deepening of the Cold War. The outlines of the planes in Air Race more or less match the RAF’s brand new Canberra nuclear bombers that raced to Christchurch. McCahon was known to be concerned with the fate of mankind in this nuclear era; OBB’s foreground forms can also easily depict post nuclear devastation.

And, what now, at that time in 1952, with a powerful new style flowing through his brush, for McCahon? The immediate answer, as far as McCahon’s artistic and family life was concerned, was that when put on display in the Christchurch City Library by new librarian Ron O’Reilly, OBB attracted the eye of visiting Auckland City Art Gallery Director Eric Westbrook, who, after he saw the painting, contacted the painter. From that contact, both painting and painter moved to Auckland and the ACAG. Even then, McCahon was still obliged to get his foot in the door by starting work at the gallery as a cleaner. It was a re-beginning, starting at the bottom again, but McCahon was more than a match for any adversity.

McCahon’s earlier figurative style remained behind in the South Island. The intuited question of, 'what now?' is soon answered in 1954’s sculpturally three-dimensional and frame-filling, ‘I AM’. Victory Over Death (1970) and The Gate Series are foreshadowed in this three letter proclamation which develops the foreground/picture plane object-monumentality seen in OBB. This development of pictorial elements from OBB further reoccurs, in that there are parts of OBB that became complete paintings in many later works; Here I Give Thanks To Mondrian, the various landscape series, the Urewera paintings, etc. The seeds of later black and white works lie in the black oblongs at the foot of each of OBB’s panels, like ingots of nuclear obsidian or diabolical pitchblende. This bridging from his past and foreshadowing of his future is what marks this work out as significant.

On Building Bridges exemplifies one of Colin’s teachings to us, his 1965 painting class; Robin White recounts how he once stated that, ‘to paint is to contrast’. Going by the hunch that Colin was giving back beauty, then that beauty can be seen in OBB in the depiction of the classical geology of glacial moraine-created landforms, in the wonderful sense of light filled space, in the high angle view of the Canterbury Plains, curiously hanging, painterly hinged, below a ground level view of the scalloped flat-topped terraces. The contrast then occurs with the hideous, blood-rust encrusted, industrial machination forms of the foreground.

My first encounter with Colin McCahon in the introductory painting group class at Elam in 1965, devolved into a challenge some posed to him regarding the relevance of painting in the face of the motion picture; that the moving image was more powerful, was the medium for the age, and relegated painting to being a relic. McCahon’s retort was that painting’s strength was in the very fact it was not moving image. During a teaching session in our painting class, McCahon once defined a painter as an artist ‘who has to paint’. The fact that I became involved in motion image while at Elam in my collaboration with Rodney Charters in the making of Film Exercise (1966) may seem to suggest a rejection of painting as a means of expression, but not so, it is simply how providence has worked.

I do have a moving image project that I have been trying to pull off since before 2015. The project is a digital cinema examination and exposition of On Building Bridges. The plan is that, in the presentation some of Colin’s students, and notable artists among others, will speak to the painting in the setting of the AAG, and also about their dealings with its creator. I put the question of whether it was going a bit over the top to make one painting the subject of such a presentation to Robin White during a recent art fair here in Sydney. Dame Robin’s reply was, ‘Why not? A great painting deserves to be made known!’

The accompanying photographs show Colin in two of his teaching modes. The photo where he is standing captures a quintessential Colin-making-a-point moment in the latter half of the 1960s. The gesture and stance are that of giving. His facial expression is that of the sorcerer seeing if the apprentices are absorbing the revelation. Or so it seemed and still seems. The place looks to be the Elam painting class and the paintings reveal the students’ outcomes to Colin’s eggs-on-a-plate exercise, which was meant to give a grounding in the basics of observation of three dimensions and subsequent translation into two dimensions. The second was a moment of one-on-one, Colin and myself at The Kiwi pub in my last year at Elam, 1968. The body language says what is transpiring; I often felt foetal before some of Colin’s insights. Colin McCahon’s generosity of spirit and the giving of his knowledge are visible in both moments. Grateful thanks to Max Oettli, for the inclusion of his photo from his upcoming book of photos from the Kiwi Hotel. Stuart Pilkington is the photographer of Colin teaching at Elam.