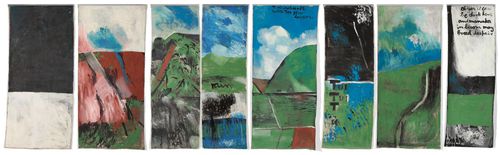

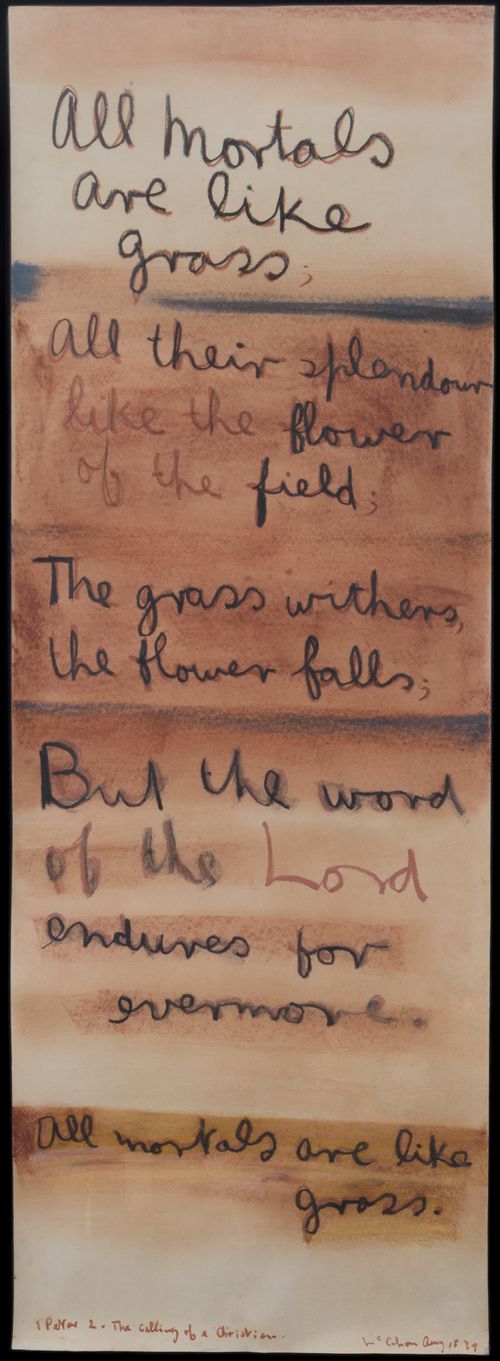

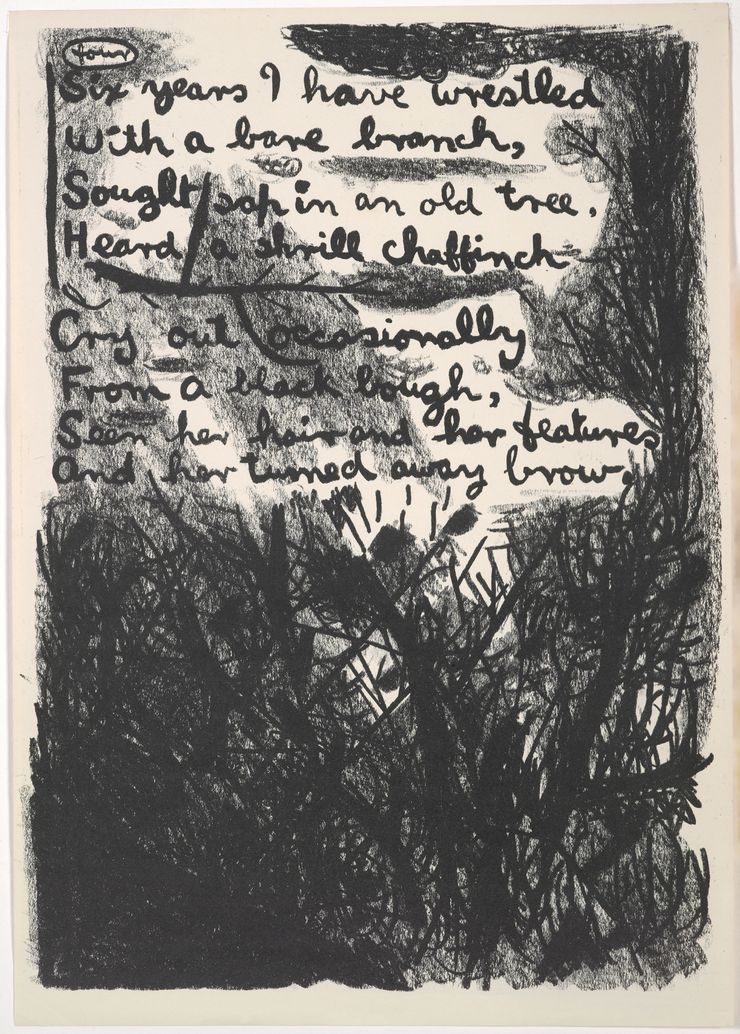

Van Gogh - poems by John Caselberg

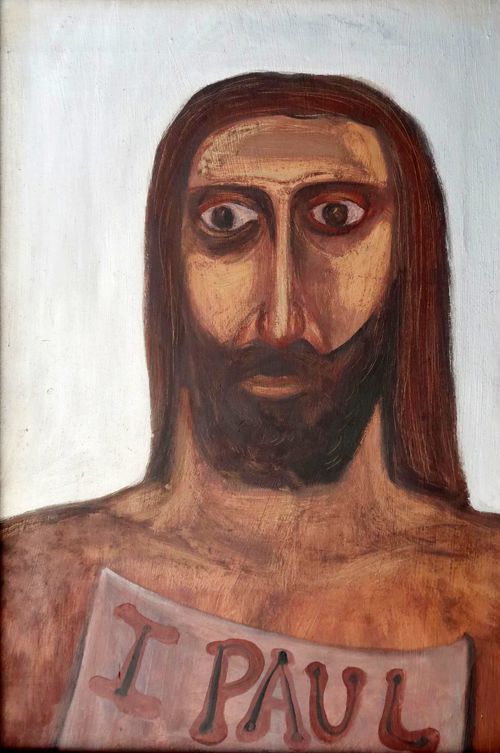

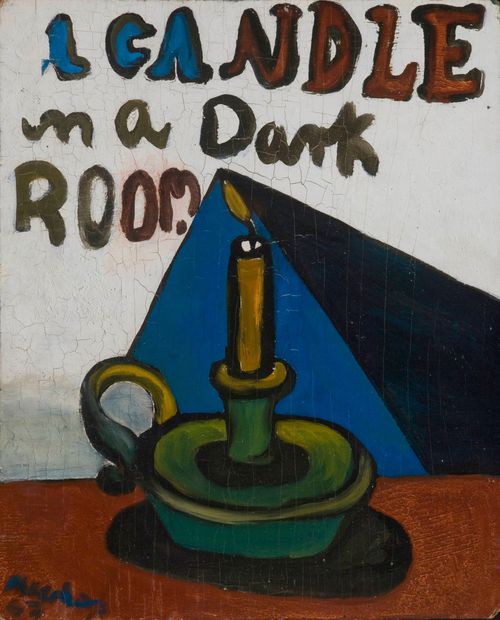

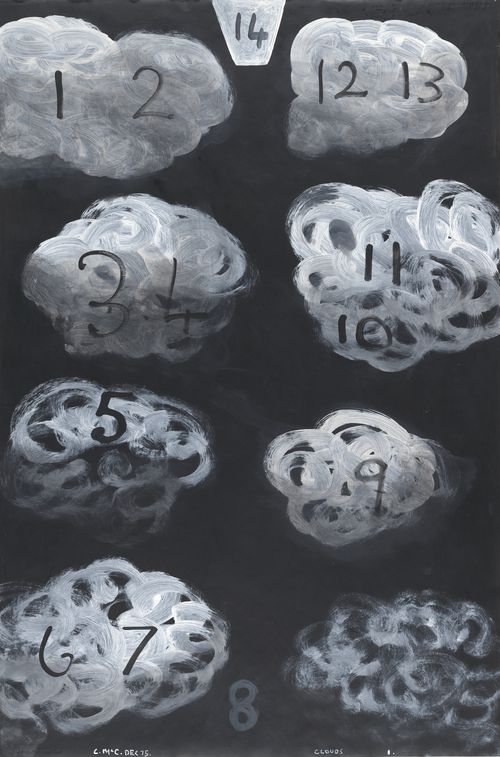

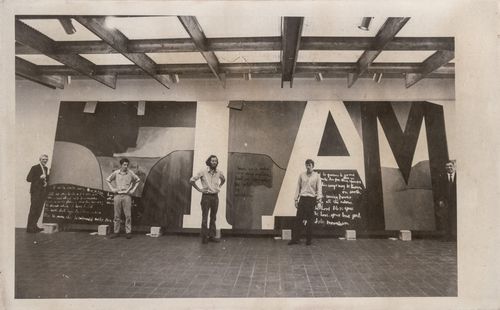

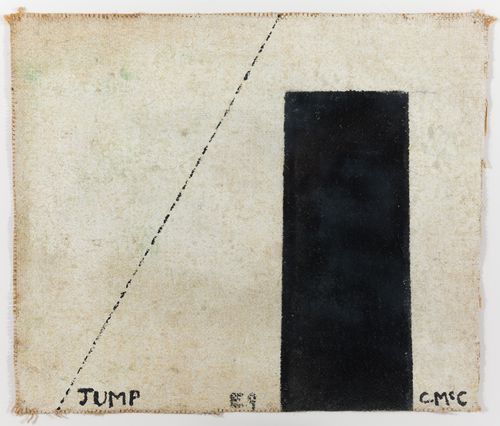

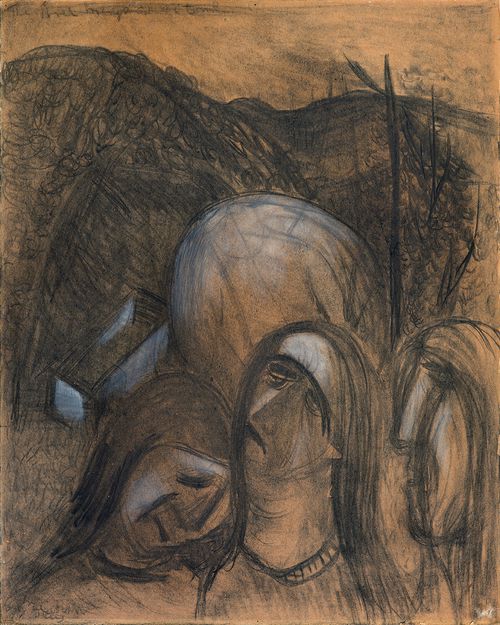

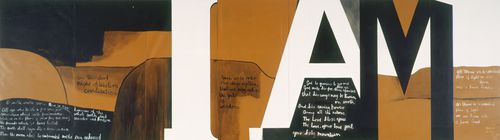

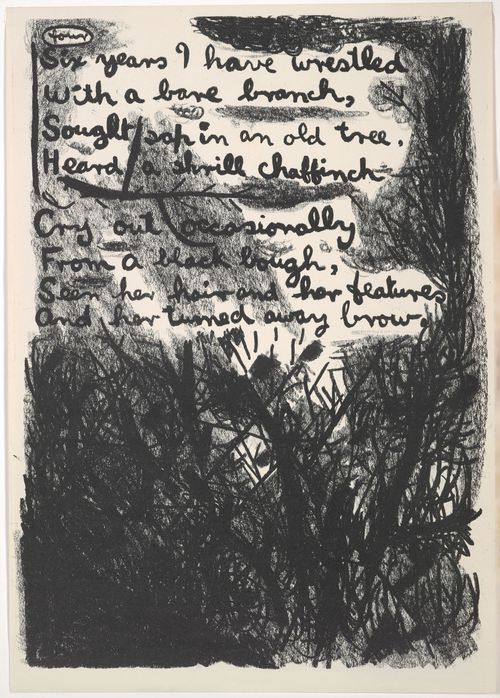

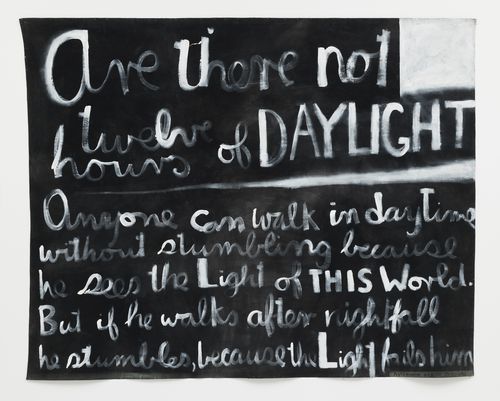

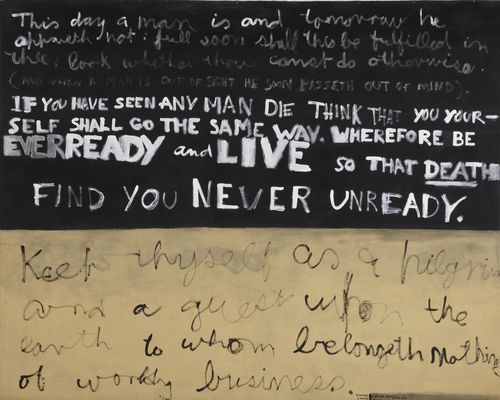

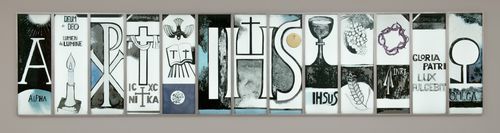

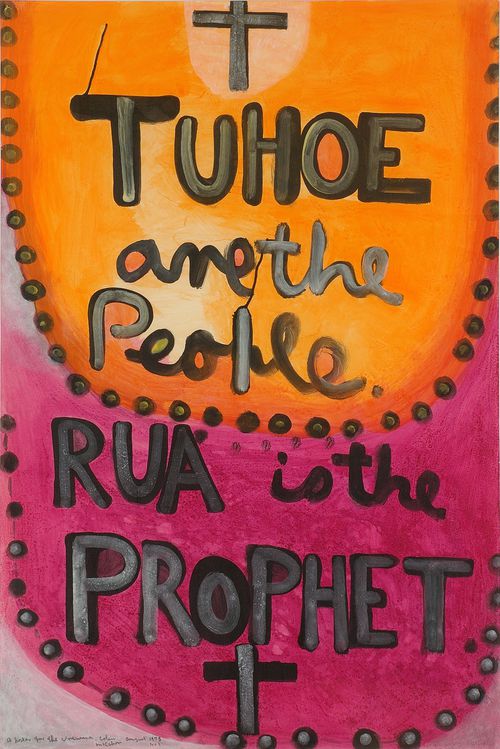

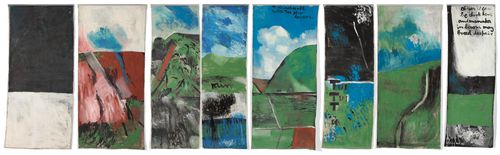

Colin McCahon, Van Gogh, poems by John Caselberg, 1957. Collection of Museum of New Zeland Te Papa Tongarewa. Purchased 1982 with New Zealand Lottery Board funds. Courtesy of the Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust

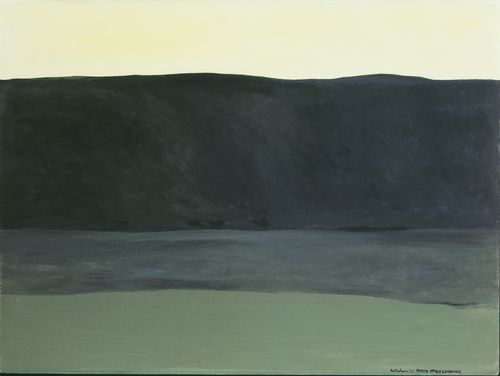

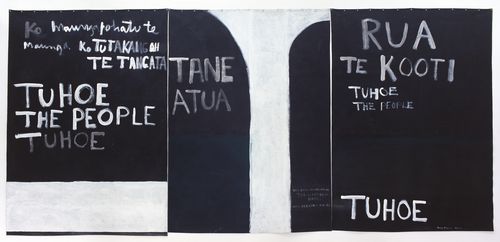

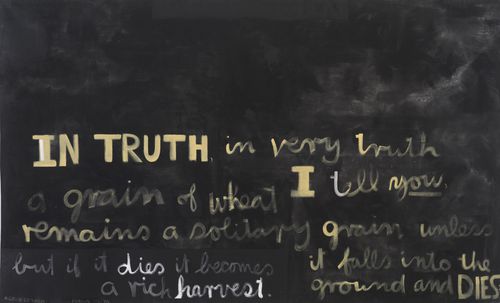

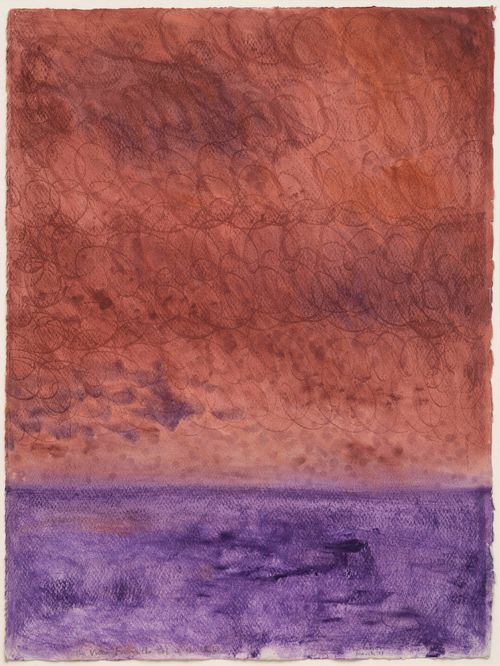

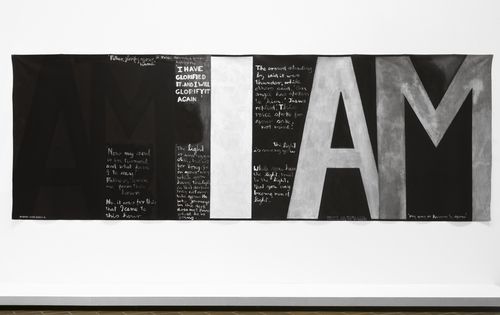

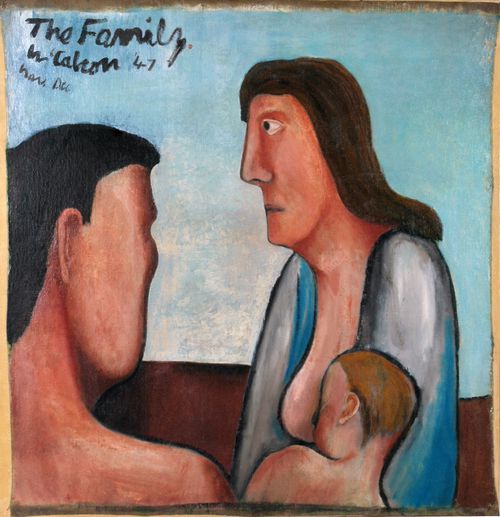

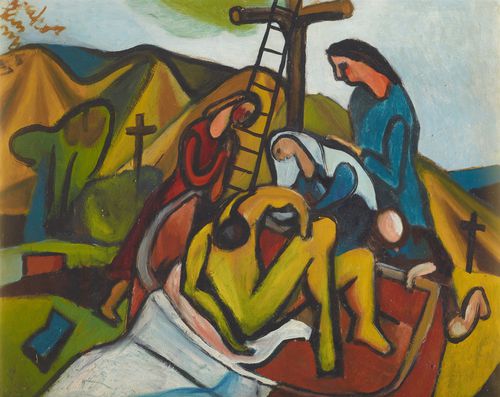

Sophie Bannan, No title (from the Waiuta series), c-type print, 50 x 60cm, 2018

Sophie Bannan

With my head currently in my thesis, deviating into thinking about McCahon has felt traitorous.

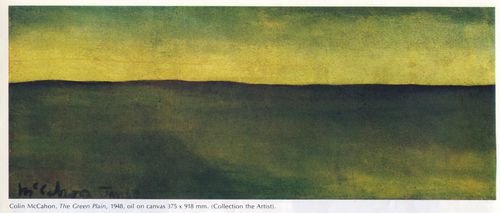

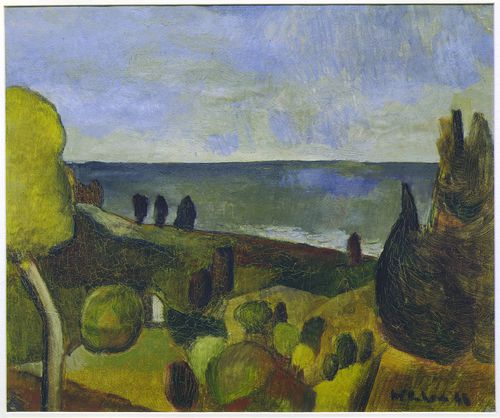

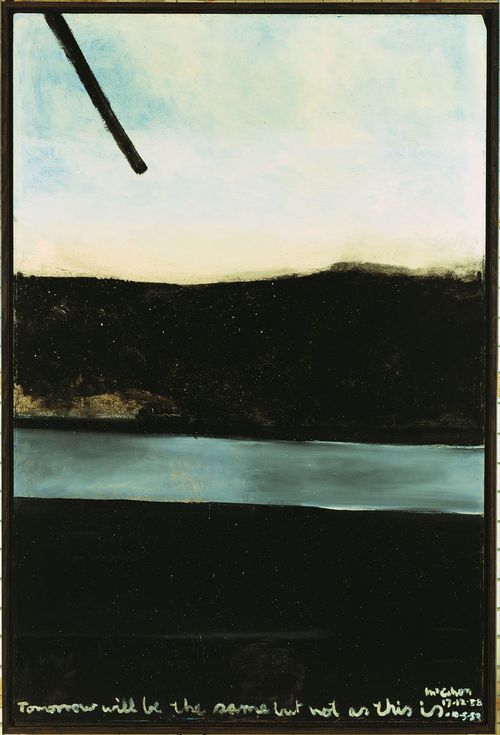

As a teenager, McCahon’s large scale paintings in the Christchurch Art Gallery’s collection resonated with my moodiness – I named my own ‘dark’ paintings and sketches ‘Tomorrow will be the same but not as this,’ and in art history essays claimed these encounters to be experientially poignant.

Later I wrote a university art history essay about the Northland Panels. My memory of this essay is that it was probably the best thing I had written to date and was granted a measly B from a tutor who ‘didn’t understand me’ – (lingering inner teenager). I managed to track the essay down thinking it might be useful for this text but in reality it’s… mediocre.

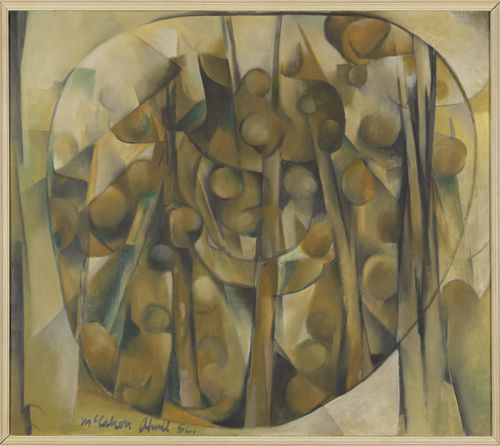

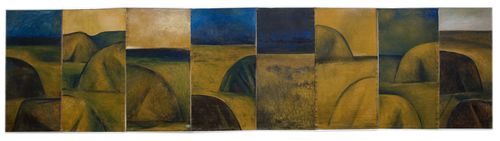

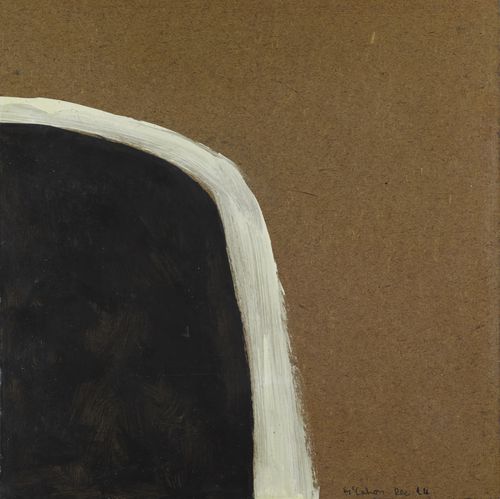

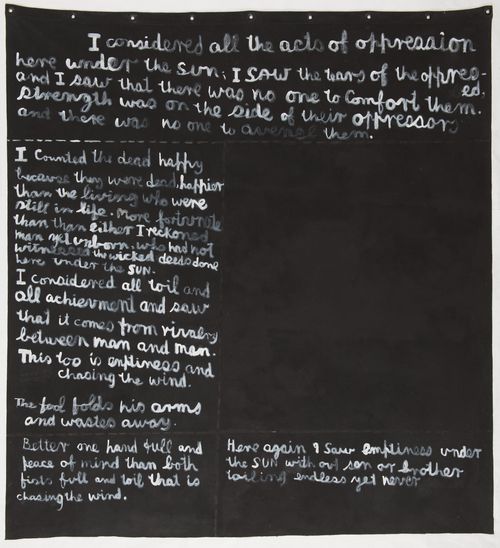

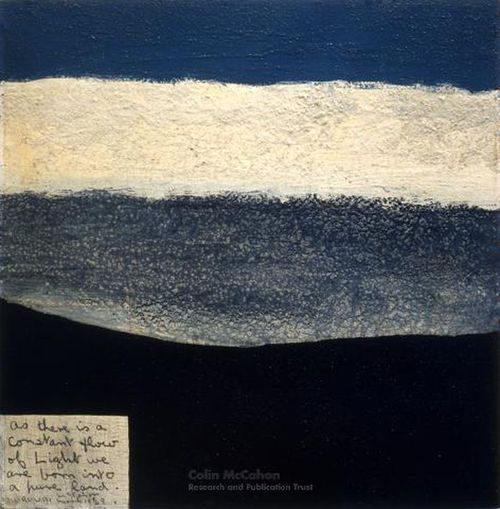

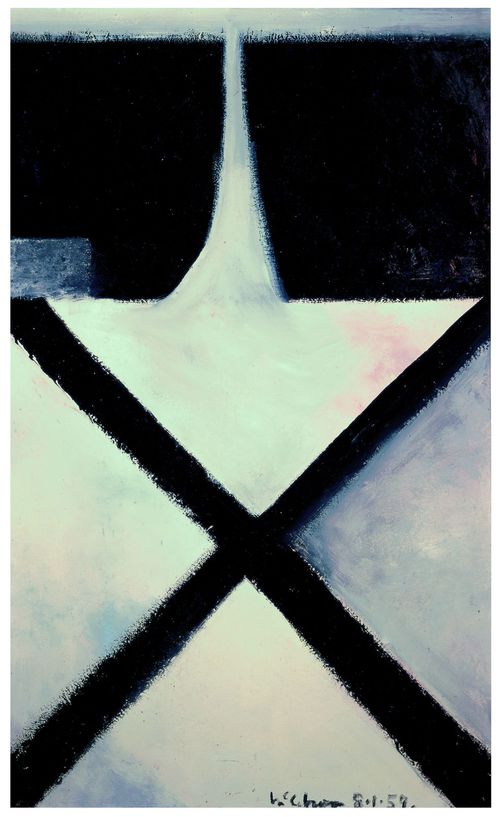

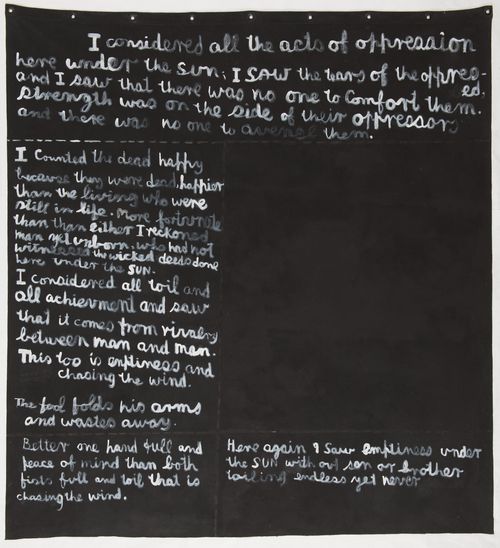

When Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū reopened following years of earthquake repairs I got a job as a visitor host and crossed paths with McCahon again. The luxury of time with the works in the gallery was not lost on me, but by autumn the boredom of standing in empty galleries on quiet weekdays was getting me down and so was the weather. Over summer I had fallen in love and my lover had since left for Sydney. Peter Vangioni had curated ‘McCahon/ Van der Velden,’ which was a small and unsuspecting show tucked away in an upstairs corner gallery. Here I was again, moody with ‘Tomorrow will be the same.’ A series of small scale works held the space against a few large paintings; ‘Northland’ ink washes, dusky and marshmallowy on brown paper, and a series of lithographs depicting John Caselberg’s series of ‘Van Gogh’ poems. The poems had been published in The Sound of the Morning (1954) and as Caselberg’s publisher wouldn’t release copyright of the poems, McCahon’s lithographs could not be sold and weren’t exhibited until 1970.

What I like about the Northland ink works and Caselberg lithographs is how they challenge my own (limited) mental narrative of McCahon and his work. This thesis I’m writing is attempting to develop methodologies for art making in and of landscape that is radically democratic, inclusive, and subversive of dominant narratives. So this is where the treachery sits for me. The company I am keeping in my reading and thinking is the work of women, mostly, artists and ancestors, and compared to an art historical heavy weight like McCahon their work is softly spoken and largely left in the undercurrents; it’s the presence of the most visible players that I’m trying to move aside.

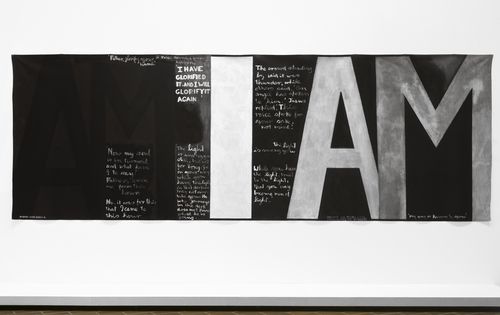

Amongst what little writing I have tracked down on the work of Christchurch photographer Rhondda Bosworth is a thorough and tender survey piece written by Peter Ireland in response to her exhibition Booklet 1 (McNamara Gallery, 2014) that, more so than addressing the exhibition itself, explores Bosworth’s covert practice and somewhat unfashionable art world status (a ‘result of a complex dynamic of perceptions, judgements and promotions that, perhaps surprisingly, can exist outside of what long-term value the actual work might have.’) In discussing Bosworth’s use of archival and autobiographical text in her work, McCahon’s ‘grand and notional’ text works are used antonymously, but Bosworth’s photographs of her father’s poems converge with McCahon’s imaging of Caselberg’s poems so amicably.

It’s a coincidence really, that I was surreptitiously thinking about McCahon while researching Bosworth then find myself reading about them both in the same sentence. I’m certainly not making any sort of suggestion that McCahon’s work set a precedent for the use of text in artwork as a feminist strategy, only that I find these coincidences pleasing, and softening, too, in that contributing to this project has challenged my own narrative of McCahon and, most surprisingly, has brought back some big teenage feelings about artworks that were, at different times, my companions.