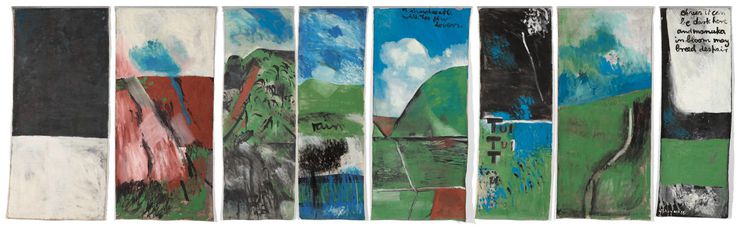

Northland Panels

Northland Panels, 1958, enamel on canvas (eight panels). Collection of Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington, courtesy McCahon Research and Publication Trust

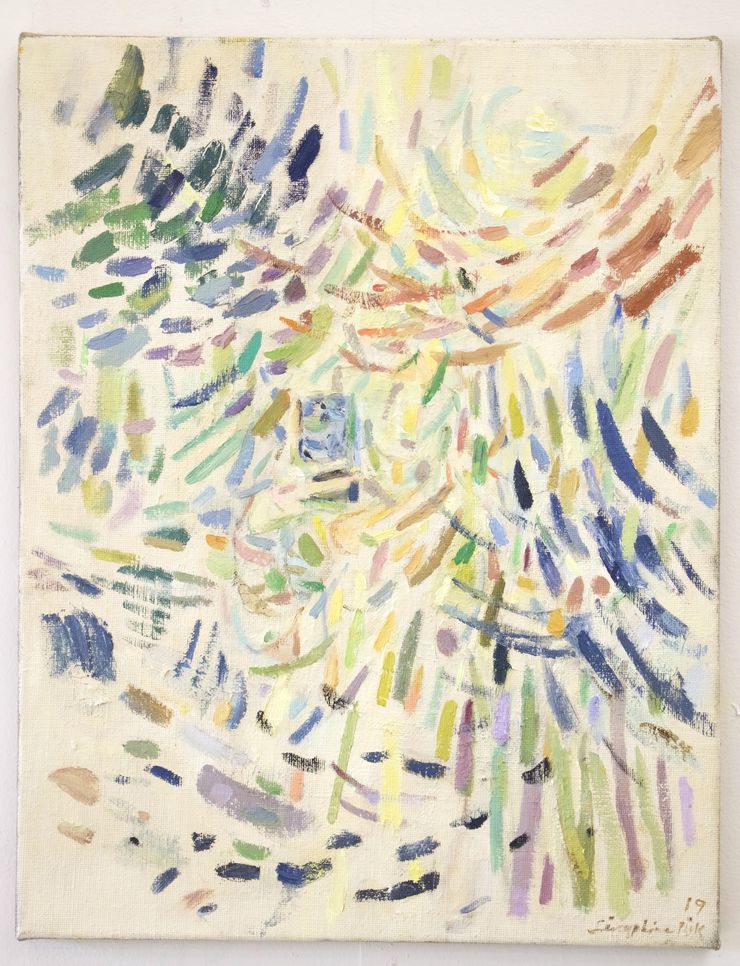

Séraphine Pick, Corporeal V, 2019, oil on linen, 450 x 350 mm

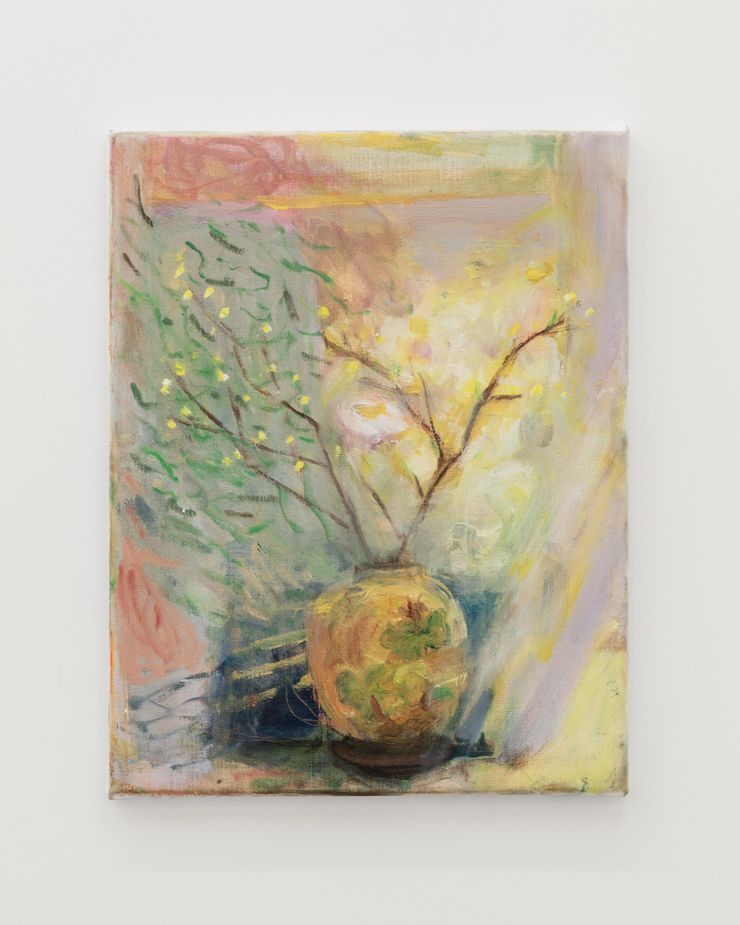

Séraphine Pick, Still life (soft fascination), 2020, oil on linen, 450 x 350mm

Séraphine Pick, Whisper, 2020 oil on linen, 1540 x 1360mm

Séraphine Pick, Untitled (Mingled), 2020, Oil on linen, 450 x 350 mm

Séraphine Pick, Trace, 2020, oil on linen, 600 x 500mm

Séraphine Pick, Seventh Sense, 2020, oil on linen, 1300 x 1050mm

Séraphine Pick, Guru, 2015, oil on linen, 1600 x 2000mm

Séraphine Pick

I was in high school at Bay of Islands College in the early 1980s when my art teacher Selwyn Wilson took us to Auckland to see McCahon paintings that I first encountered one of his paintings.

I remember my experience seeing the Northland Panels (1958). The scale of the work impressed me first, then the energy in the brush strokes. Walking along it, it reminded me of the bus ride I took every day to school in Kawakawa. The painting was just like the frames of bush and skies flicking past through the windows of the bus. I thought it was very filmic with each scroll of canvas like stilled moments of seeing. It was so familiar with the intense green of the land, blue skies, voluminous clouds and the scaring of red clay. My father was a potter who gathered clay from Northland, so I recognised that colour of earth. There were always slips in the winter rains; the clay got wet and dried and then crumbled onto the roads.

The words on the painting were puzzling for their feeling of foreboding. ‘Oh yes it can / be dark here’ - ‘Manuka / in bloom may / breed despair’ - ‘a landscape with too few lovers’. Scrawled in black in the sky like a flock of birds flying by, these words all made sense to me in different ways; about my place of birth, its dark history, its beauty and the talk at the time of climate change and the human impact on the landscape.

In 1981 my father took me to an exhibition of Colin’s in Auckland at Peter Webbs. I saw the painting Storm Warning (1980) with its powerful message all in text on the painterly fiery surface of a loose canvas. ‘YOU MUST FACE THE FACT’, it shouts, ‘the final age of this world / is to be a time of troubles, ‘men will love nothing but money and self, they will be arrogant, boastful and abusive; with no respect for parents, no gratitude, no piety, no natural affections they will be implacable in their hatreds.’ I had no religious context for the words, they read firstly as images of letters, the painting itself, then as messages of what was happening in the world; the combination communicating the emotion of the artist. I read it as an environmental warning at the time. Peter Yates, a potter friend of my parents went on small yachts from Russell to Moruroa Atoll to protest the nuclear tests, so I was well aware of the environmental politics at the time and this painting made me see how you could communicate through art in a powerful way without losing the language of painting: the strong message within the painting upon strong loose brush marks of colour, lightness and darkness. It seems his message could still apply to today.

I have only more recently begun to look more closely at our early New Zealand modernists, having been discouraged to look at New Zealand artists while at art school in the later 80s. I love McCahon’s Titirangi series; the reduction of dappled light through trees to dancing rectangles of vibrating colour; almost digital pixelation to our contemporary eyes. What we see is an abstract collection of shapes which relate to each other in space creating a sensation, a feeling, an experience of nature.

My more recent work is moving towards semi-abstraction exploring an intuitive and bodily awareness through painting on a large scale. Colin McCahon’s work resonates with me in the way he used an economy of marks and fields of tone and colour to convey light nature and the presence of the body in it, through its absence. You become very aware of yourself being in the paintings’ vast spaces. The way light is conveyed with a minimal brushstroke of an intense white or yellow - you look at it as an experience that you know you have had in the physical world - the New Zealand landscape - transforming you to another space and time. You sense his presence in them too as they are often physically large paintings and he would have used his whole body to make them. There’s an intense energy and urgency in them. Other favourites include Walk (Series C) (1973), The Gate series (1962) and The Wake (1968), all works you physically move your body along to view as a journey reminding me of places I have been and lived in.

Painting is a contrasting thing to do in this world of the digital, where we spend more and more time in the virtual world. I have had moments of feeling that painting is redundant in this Covid-19 world. But then it has also felt more necessary than ever, as it is tactical, primal and an essential human activity using both the body and the mind to communicate. It somehow brings me back into my body, into the present, I filter the world through it into edible marks, my feet are on the ground, it takes me forward through time, keeps me moving and observing the world, connecting and reflecting.