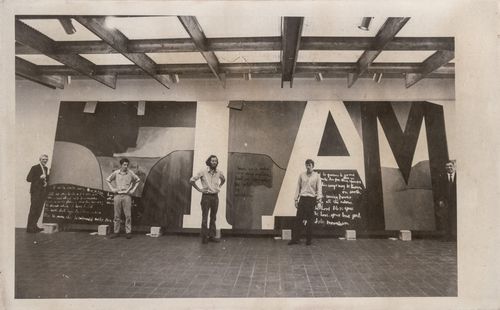

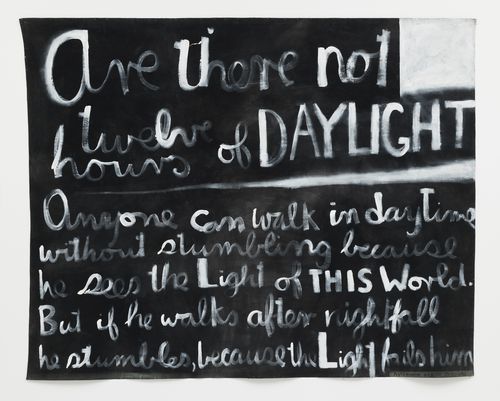

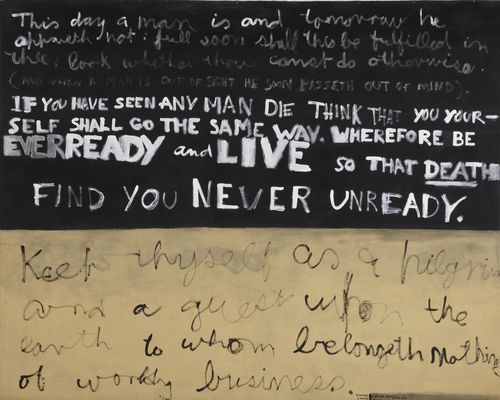

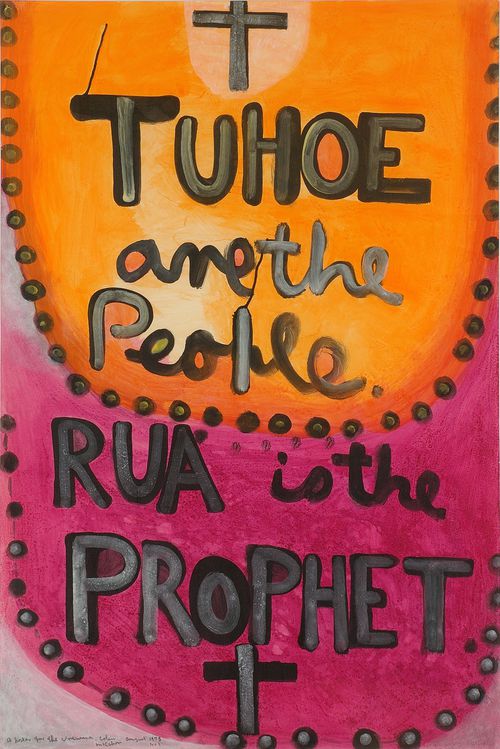

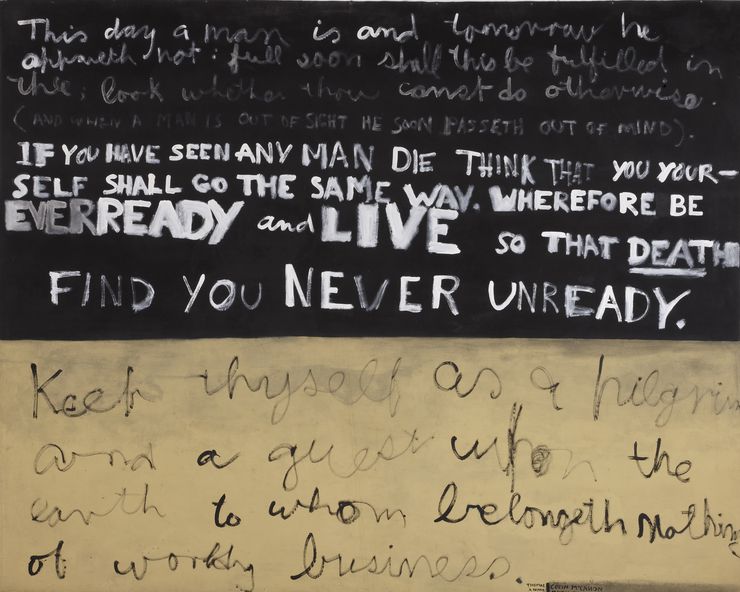

This day a man is

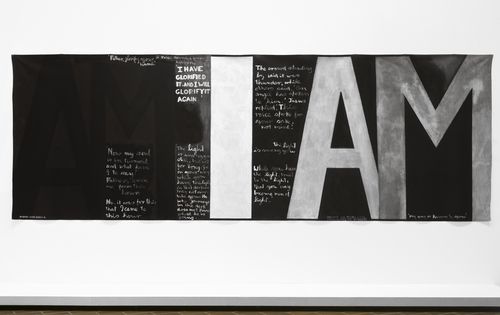

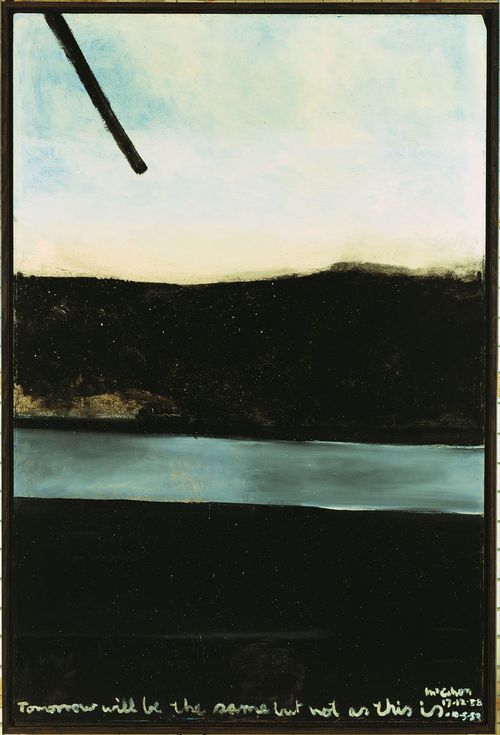

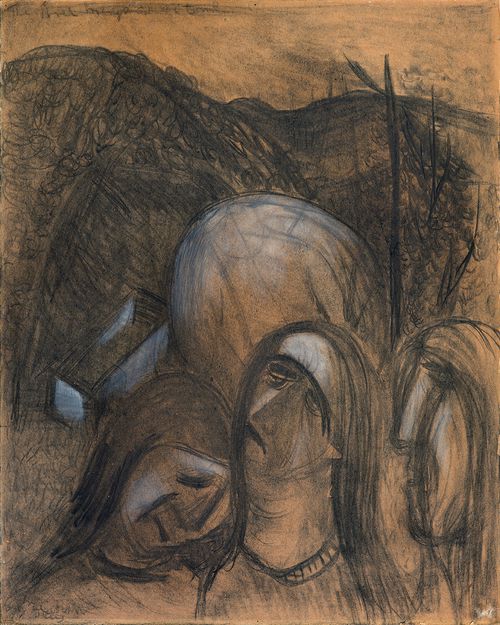

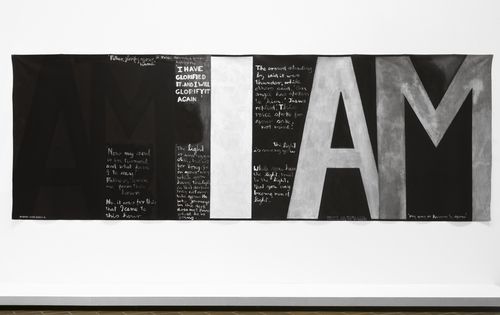

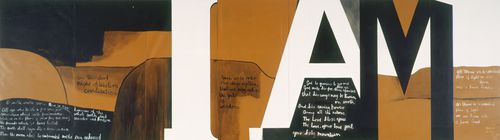

This day a man is, 1970, synthetic polymer paint on unstretched canvas, 2080 x 2600 mm. Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, courtesy McCahon Research and Publication Trust

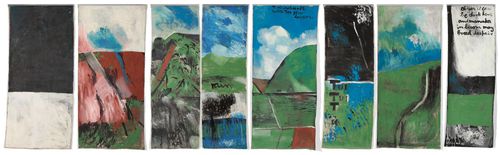

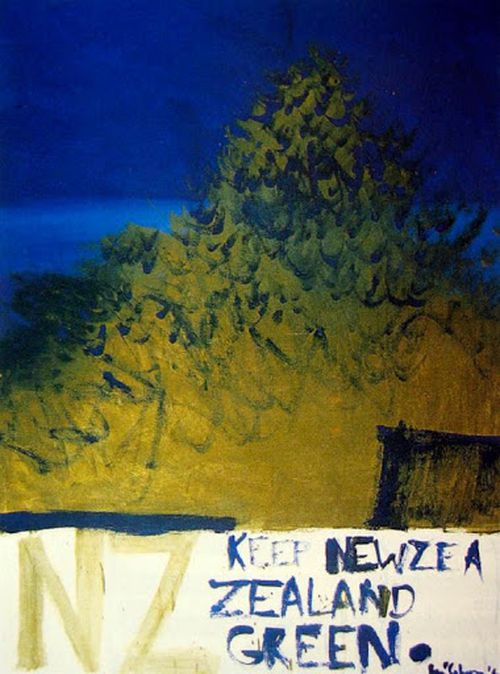

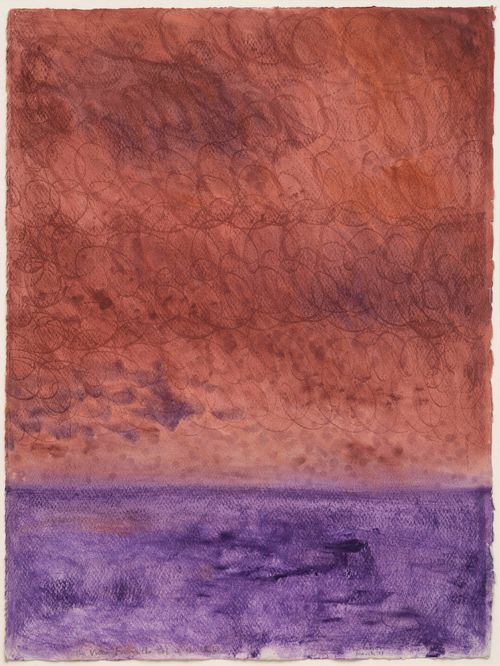

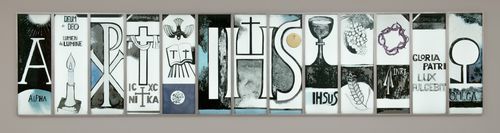

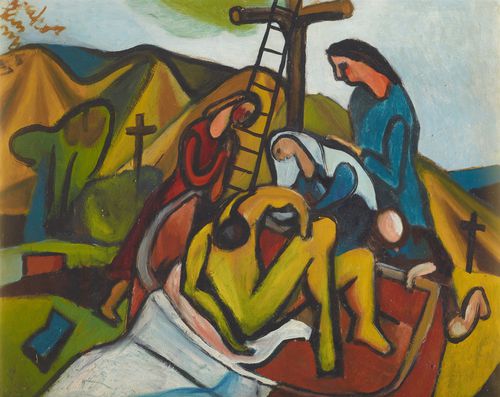

Grant Lingard, Swan song. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū; gifted by Trevor Fry, 2013

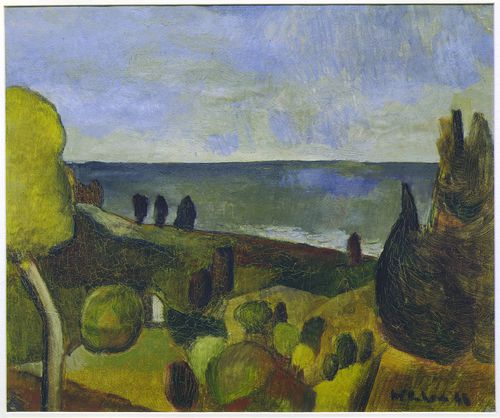

Swan song during installation, 1996. Left to right, Mary Kay, Graham McFelin, Teri Johnson, Peter Lanini, Ruth Watson. Photo by Trevor Fry

Ruth Watson

Unprepared

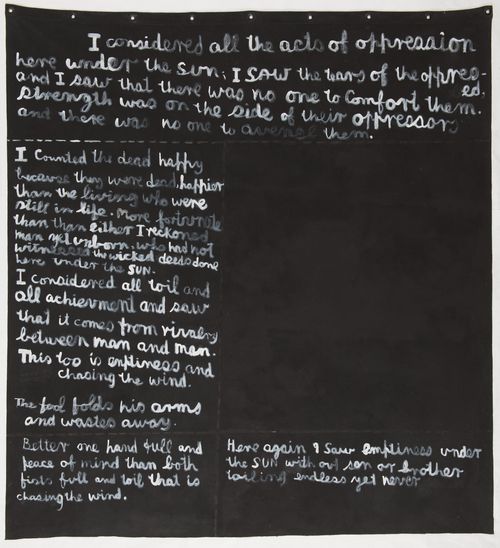

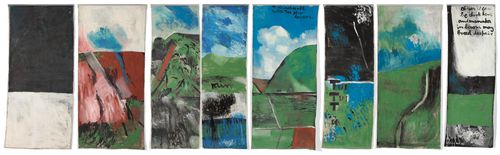

When I lived in Sydney I was an artist working in the gig economy, moving from one part-time job to another. I did this for 22 years after leaving art school and it was not easy – although I did manage to move countries three times, something I look back on now with trepidation (ignorance or denial of what that entailed was clearly a key driving force). Love of art, not all of it of course, remained constant and I’d long recognised McCahon’s ability to make you see the world through his eyes, whether that be hilly ranges in the South Island or his painted words that challenge expectations of nicety. This raw intensity made it difficult to accept other artists’ hand written words – it took me years to appreciate French artist Ben Vautier’s white on black writing, like being asked to enjoy a Prosecco spritzer after years of bootleg liquor.

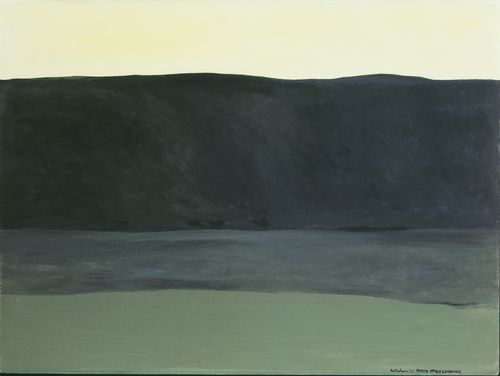

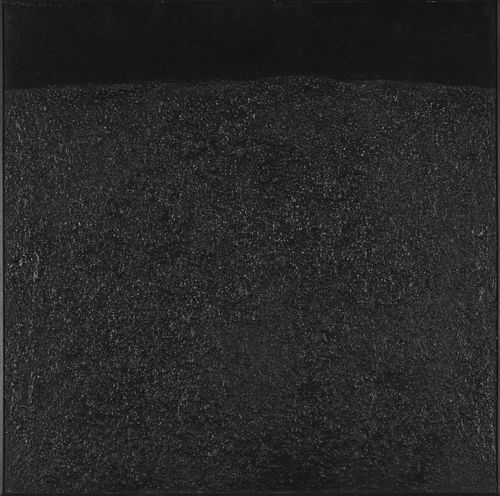

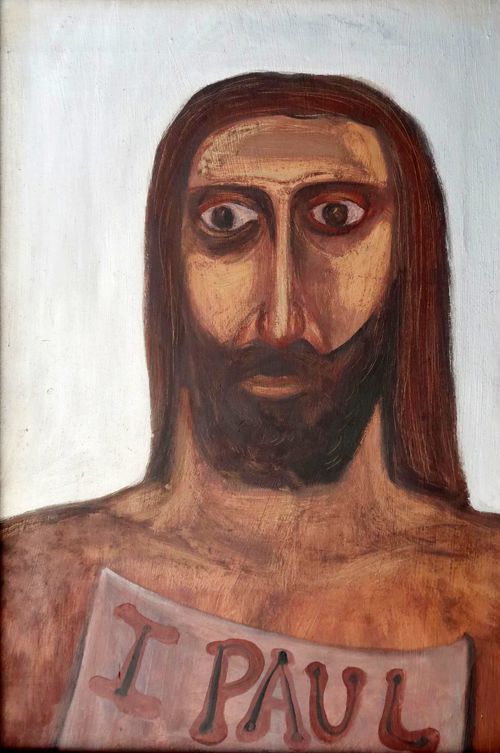

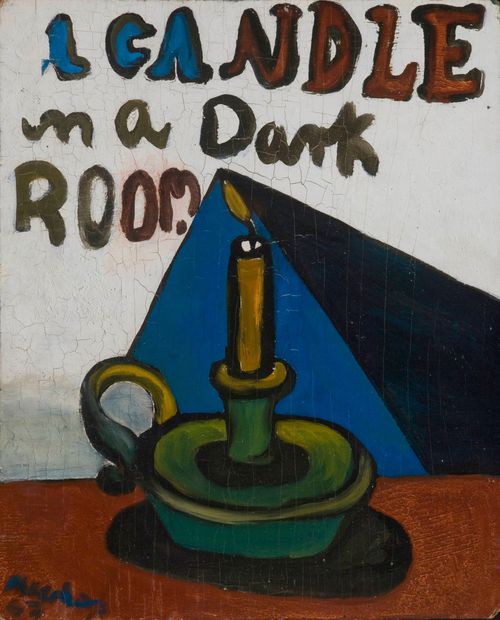

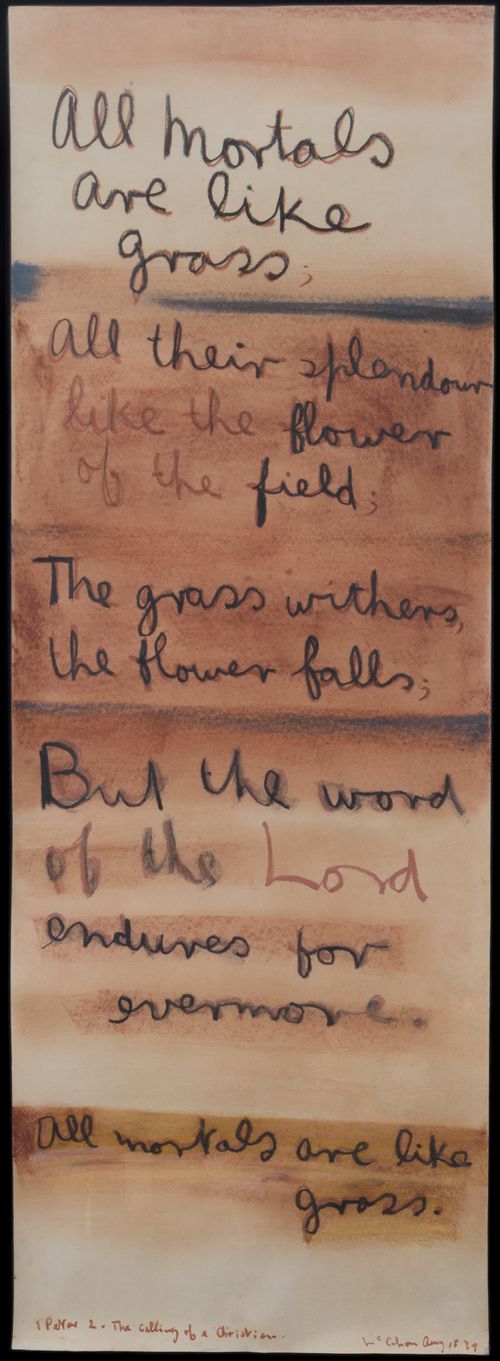

In This day a man is.... the handwriting shakes, what it writes rails. It’s simultaneously childlike and aged, like a biblically clenched fist dissolving into tears of despair. A landscape (is it one? – precedent might allow this) is rent, light from dark, the sky pitch black. Or the land dark and the sky pale, a world upside-down. It’s not the kind of painting you can take on a first date; it inspires rage in the uninitiated and fear amongst lovers.

The painted words confound with alternating vehemence and lassitude. In the lower section, paint-enfeebled brushwork might account for the shape of ‘and’ following the word pilgrim, but ‘upon’ takes you on a journey into the abyss. Below, belongethnothing contains letters that do not care if you can read them.... and is that supposed to be ‘worldly’? My tidy printout from the online catalogue says so, but I’m still not sure.

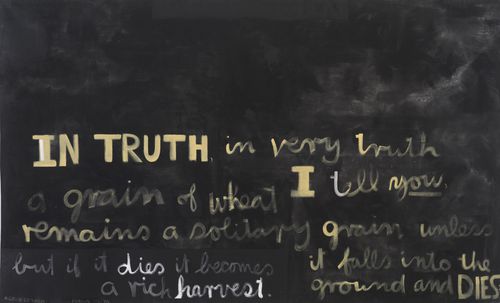

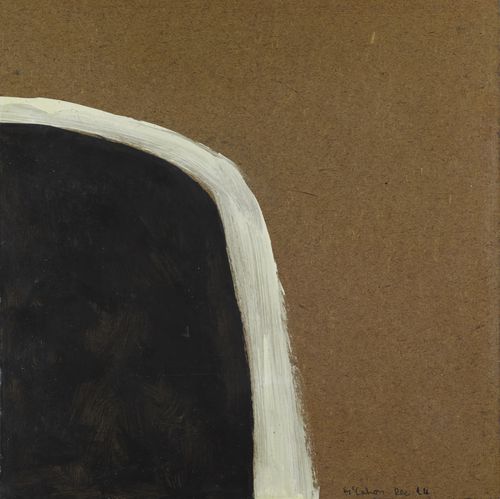

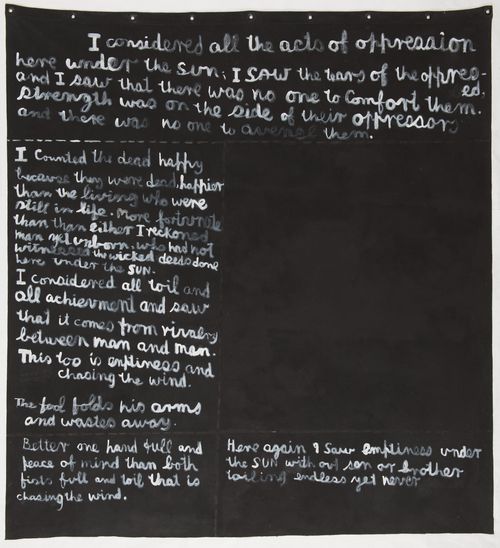

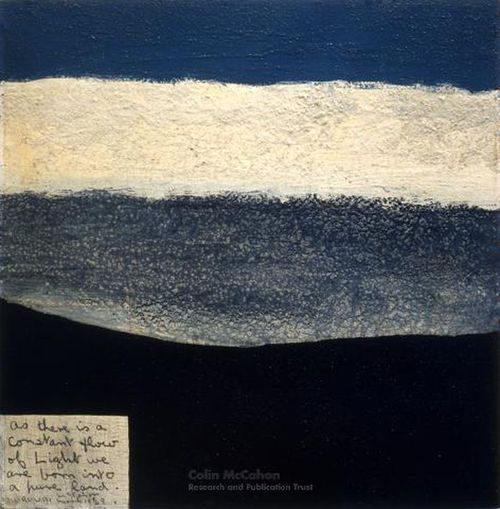

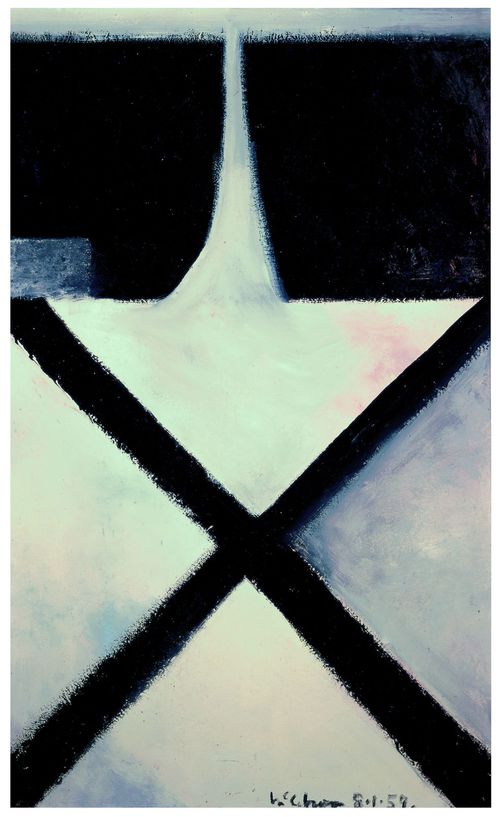

The text in This day a man is.... derives from the Imitation of Christ, Thomas à Kempis’ late medieval bestseller that enthralled the Western world for centuries, but a rare choice for McCahon. The book exhorts us to find salvation through Christ and contains a permanent tension between this being achieved by deeds and behaviour, or found through the contemplation of texts. À Kempis seemed ultimately to find the text containing the final word and McCahon, perhaps, tries to imitate – but his looping, dry, enraged, ecstatic and emphatic writing reveals dissatisfaction with words alone. And, the painting might imply, frustration with deeds, too. Few other of his works’ writing arrest with such feral wildness: perhaps only the ‘oh God’ of the 1959 Northland Triptych, the ‘o’ of God blacked out and drooling lines of dark paint against a pale background, as if an eye had been put out under torture.

I stood in front of This day a man is.... in Sydney decades ago but can easily recall finding myself queasy, with an escalating vertigo. Queasy because the way words are painted takes you on an exhausting journey to a place you recognise as raw, difficult and contested, to the core of a struggle. Is the handwriting alcohol-induced? – probably, but I don’t think that negates the achievement. Going to the MCA meant escaping from whichever job I was in at the time, walking past Aussie icons of Bridge, Opera House and twinkling harbour, finally halting in front of this work with its insistent demand: confront your mortality.

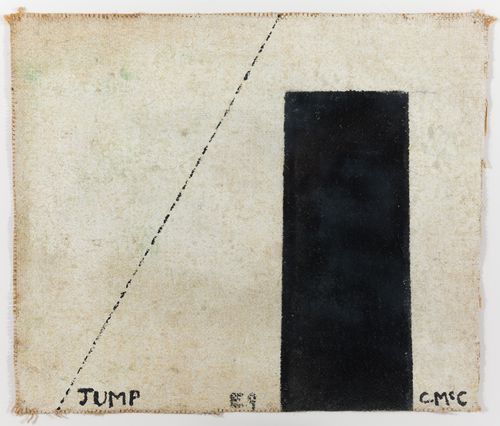

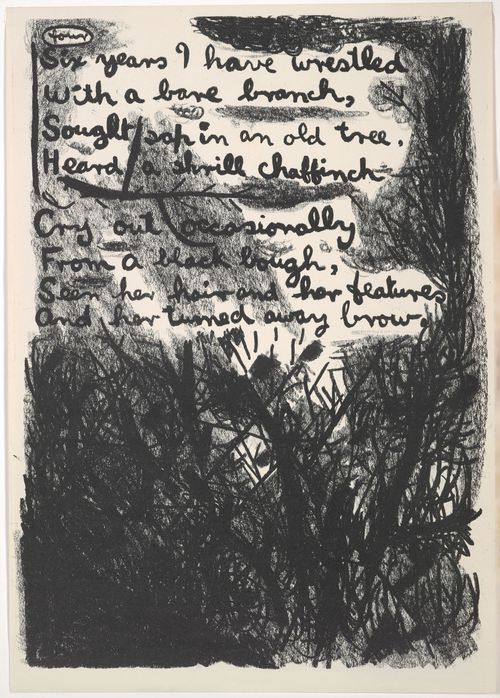

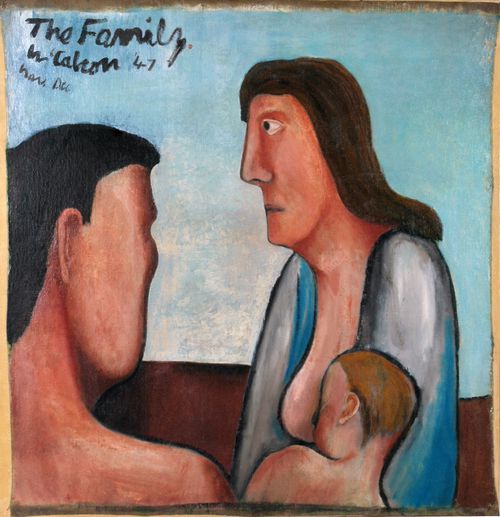

My job by then was bracing, doing data entry for a research centre with the daunting acronym of NCHECR (National Centre for HIV Epidemiology and Clinical Research), in Darlinghurst. I plugged pre-coded user information into a national database for a drug called Zidovudine, perhaps better known as AZT, one of the first antiretroviral drugs to slow the progress of the HIV virus. It was already being superceded by new medicines, protease inhibitors, and was now merely part of a drug cocktail shifting outcomes from what had been a death sentence into a chronic manageable illness. So ‘my’ database wasn’t as critical as it once had been, part of the rapidity of change around this pandemic. Shortly after arrival in Sydney I’d got in touch with some friends from art school and Grant Lingard was one of these. We had a long phone conversation but at the end I thought, what just happened, we didn’t make a time to meet up... Within weeks he had died and I was at a funeral and wake. Given the pre-coding, it’s not impossible that his name was amongst those I’d entered into the database, but I don’t think so. It was all so fast he’d jumped from wellness to illness with relatively little time in between.

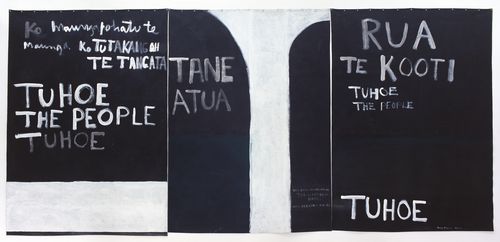

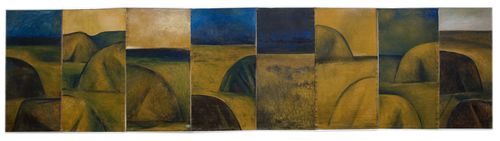

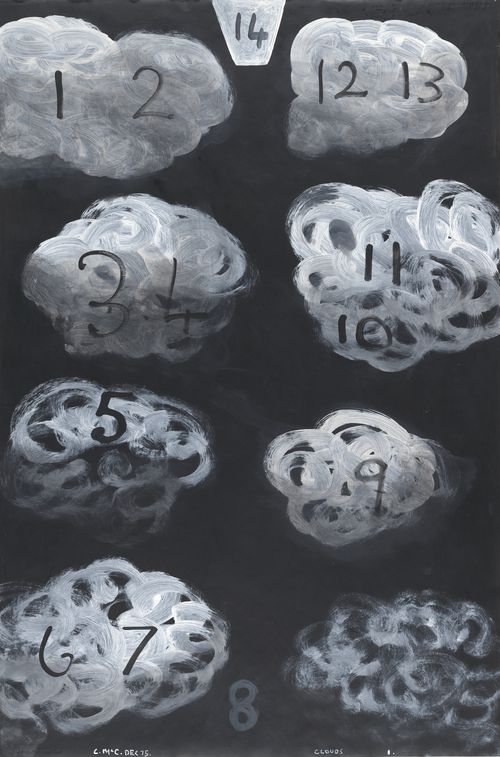

Later, a group of his friends installed his last show at First Draft Gallery, planned while he was unwell: Swan song. We tarred and feathered a very long wall (latex underneath to be simply peeled off later; Grant knew how this was best done) and, under instruction, the last eponymous work was prepared, comprising screeds of white linen – multiple iterations of towels, sheets and pillowcases – hung over a suite of white wire drying racks. Grant knew he was dying and chose to make a work that spoke to his condition. As a representation of serious illness (messy, time consuming, all consuming), Swan song seems low on emotion, without histrionics. Its repetitions represent the ongoing hassle of everyday life with disease, of being fixed to mundane activities, addressed in a very simple, elegant way. For an artist who in earlier works aired a lot of seemingly dirty linen in public, Swan song remains very fresh to me.

Death (the only word underlined) is present in This day a man is...., not just in the words but in the lower painted text’s trailing decreptitude. The mystically-inflected text exhorts us to be ready for death – or more fatiguingly – to be never unready. Death, here, doesn’t seem like the start of union with Christ but something more final, or more alarmingly, more present. I look at McCahon’s words and they still remind me of you, Grant, and [Grant’s partner] Peter, also now gone. Peter would have given a sharp intake of breath while flashing his eyes in agreement with the sentiments, then burst into loud belly laughing at too much seriousness. What if you have too little time to be prepared, where does this exhortation get you then – a question now part of the near-teetering fall into the void the painting offers, should you give yourself over to it. I look back on my encounter with this work and remember the feeling of not being able to feel my feet on the ground anymore. I was unprepared.