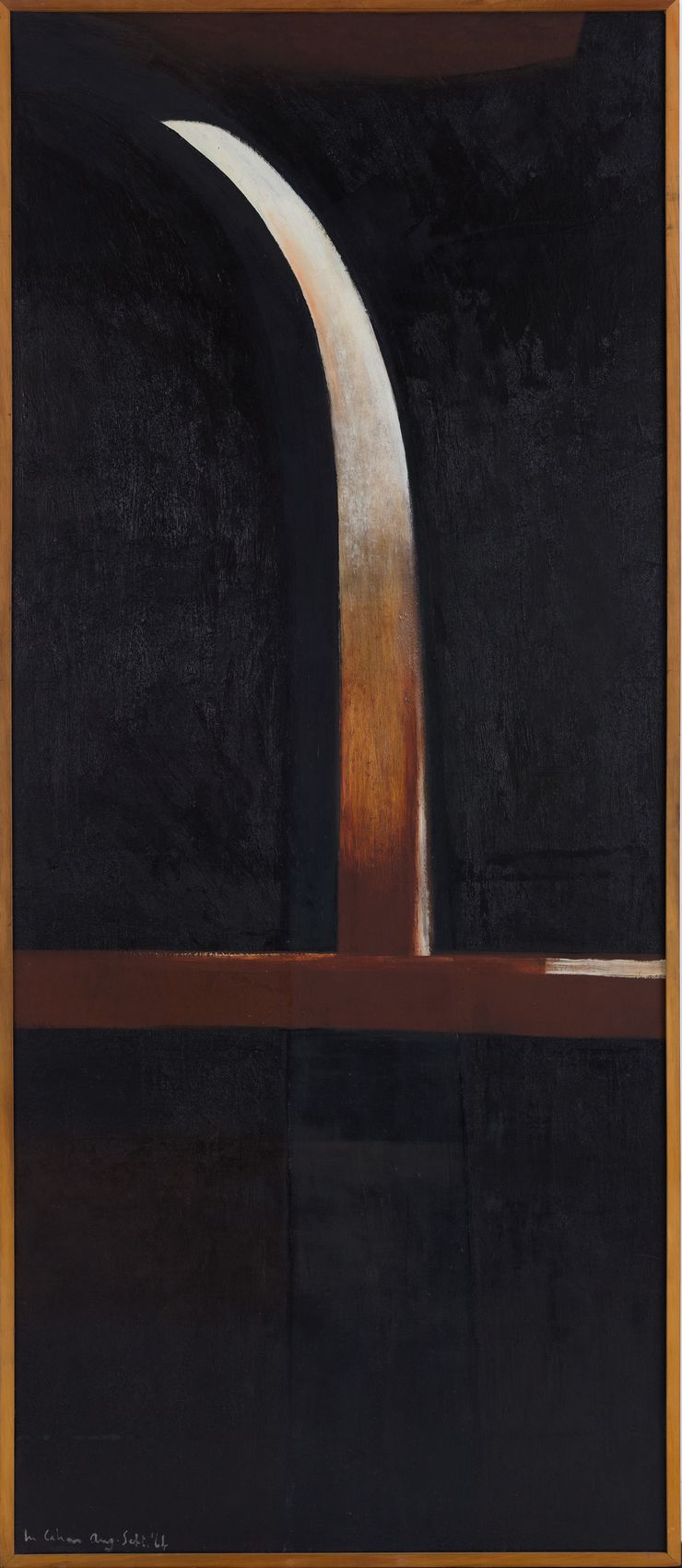

Waterfall

Waterfall (Waterfall series), 1964, enamel on plywood, 2133 x 908 mm. Collection of Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki. Courtesy McCahon Research and Publication Trust

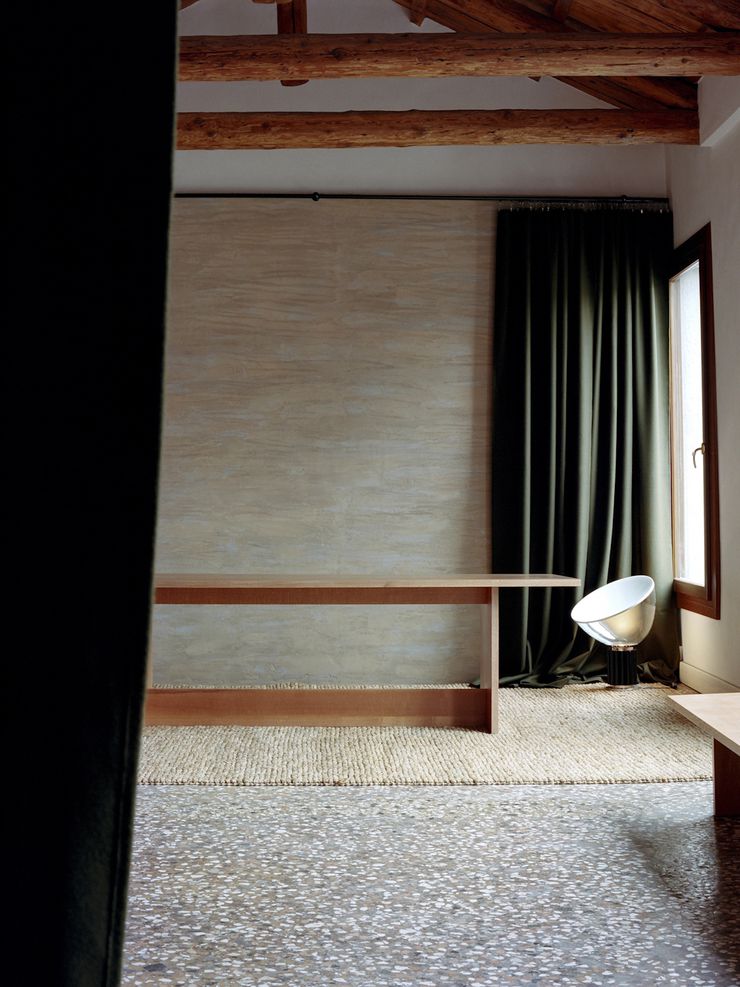

Te Koha – New Zealand Pavilion – Biennale Architettura di Venezia 2016

Te Koha – New Zealand Pavilion – Biennale Architettura di Venezia 2016

Photographer, Mary Gaudin

Te Koha – New Zealand Pavilion – Biennale Architettura di Venezia 2016

Photographer, Mary Gaudin

Rufus Knight

Panta Rei – All Flows. Heraclitus’ 6th Century aphorism on impermanence speaks to one never stepping in the same river twice. The prismatic qualities of constant change saturate McCahon’s Waterfall works and provide fertile ground that exists somewhere between abstraction and landscape, between melancholy and emboldened expression.

Borne of the mud, the bark, the whenua, the stewed palette of the Waterfall works speak distinctly of our place in the South Pacific and McCahon delivers a weight and sophistication despite the absence of written word or overt symbol. What continues to register with me about the Waterfall series is the unwavering vitality within the purity of his gesture – the paintings are always fresh, somewhat rapturous, and reveal a fragment of the ‘layered and orderly but not yet communicated’ environment we have inherited because of his unwavering vision.

The enamel on hardboard exhibits a primitive and colloquial universality. Typical of our national psyche, McCahon prioritizes performance over aesthetics while capturing the exposure and power of our natural environment. McCahon’s journeys into the Waitākere Ranges that influenced the works are symbolic of his intrepid unearthing of the Waterfall’s spiritual and romantic trope in which he is able to distil and exhibit a uniquely South Pacific ‘sublime’ as the works range from graphic abstraction to lucid atmosphere.

According to Paton, the ‘constant flow’1 of the Waterfall works represent a philosophical shift in the Western monotheism of McCahon’s work to date, introducing notions of Eastern region and the representation of light as ‘enlightenment… not just the redemptive light of Christianity’.2 This sentiment has always given me some hope that despite the vast solemnity of McCahon’s canon there existed an exploration into our unique geography and relationship to nature that was gleaming and transcendent.

I have no early connection to McCahon or his work. My first impression of his work was finding the Marja Bloem and Martin Browne publication that accompanied the Stedelijk’s 2002 ‘Question of Faith’ exhibition at the Wellington City Library in my second year of university and a conversation with a close friend where he described McCahon’s episodic and religious works as ‘a man’s faith dissolving in front of your eyes’. I was curious but not swayed by these questions of faith; not until I saw the landscapes.

I feel I have immersed myself in McCahon’s New Zealand ever since; looking for the layers, looking for the order, finding my own way to communicate it. In 2016, after a working term abroad in Belgium, I was invited by the New Zealand Institute of Architects to participate in the New Zealand exhibition at Biennale Architettura di Venezia. The commission was a discreet space to sit alongside the ‘Future Islands’ exhibition, curated by Kathy Waghorn and Charles Walker, that would present contemporary New Zealand design practice on the world stage.

The space, named Te Koha, provided an area for visitors to the Biennale interested in learning more about New Zealand’s Architecture and Design industry and hosted events organised by event patrons, partners, and supporters. Over the six-month duration it was also a base for cultural events, including symposia on architecture, innovation, and the sciences. Te Koha was supported by Te Mātau, a small informal reading room, in which visitors to the New Zealand pavilion could discover more about our creative industries through selected publications and writings.

The design strategy for both spaces was to work with innovative Aotearoa-based suppliers and locally source materials in order to develop an identity for the room that was sympathetic to the cultural depth, richness, and tactility of New Zealand’s landscape. Central to this approach was upholding and celebrating Mauri – the essence which binds and animates all things in the physical world – developed under the guidance of Rau Hoskins and with a whakatuwhera ceremony performed by representatives from Ngāi Tūhoe. Tacit explorations within Te Koha were the woven Muka floor-covering, Rewa Rewa timber furniture, and the wool fabric drops from a Perendale breed located in Akaroa. This project, although small, established for me a way to work that honoured the indigenous materiality and traditional craft of our place in Aotearoa and presented it to the world within a modern vocabulary.

[1] Paton, McCahon Country. Auckland: Penguin, 139.

[2] Ibid