Numerals

Numerals, 1965, synthetic polymer paint on 13 hardboard panels. Courtesy Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki and McCahon Research and Publication Trust.

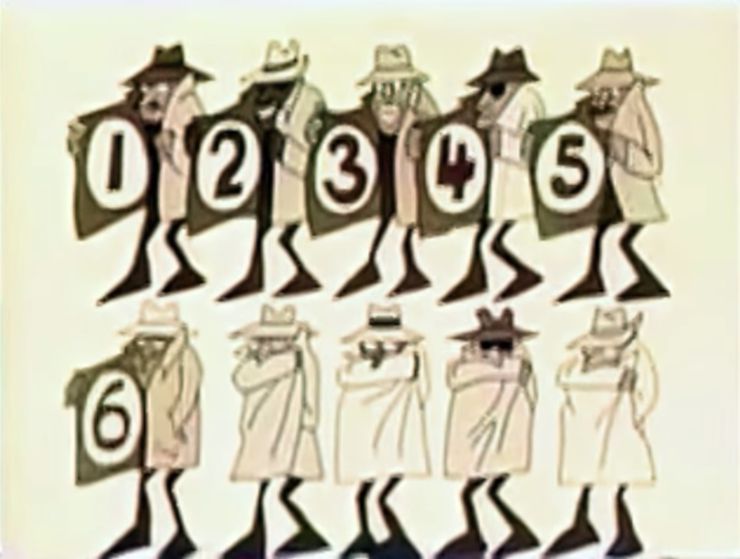

Stills from Jazzy Spies (1969) from Sesame Street. From Youtube. Video (stills), 7:01. Posted by FunkensteinJr, Jan 17 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G5stWhPNyec

Robert Leonard

It was 1999. Toi Toi Toi: Three Generations of New Zealand Artists was on show at Auckland Art Gallery, having just returned from Germany. I was there, giving a floor talk with Tony Green, my old art history professor. I went first, talking about McCahon and nationalism, provincialism, postwar reconstruction, existentialism, and religion. My audience was bewildered as I struggled with the immensity of this self-imposed task. As they went cross-eyed and gasped for oxygen, I turned around, looking to the art for help, only to realise I was standing in front of the McCahon work least relevant to my spiel. Numerals (1965) is a great McCahon, but it’s hardly nationalist, not so provincial, has precious little to do with postwar reconstruction or existentialism, and, if it’s religious, it’s only so in a glancing way. It’s not bleak McCahon; it’s funny McCahon. Professor Green was certainly amused, realising I had fallen into an old trap—not addressing the work at hand. Fail!

Actually, Numerals is one of my favourite McCahons, probably because it isn’t so deep and meaningful. McCahon began toying with numbers in the late 1950s, starting with a few pages of studies for endpieces for Landfall. His early lettering-design experiments explored the ways numerals could be constructed and deconstructed. He returned to the task in the mid-1960s. Numerals is painted on thirteen sheets of board, separately framed and butted together, making a strip about eight-and-a-half metres long. Like Northland Panels (1958), The Wake (1958), and Second Gate Series (1962), it’s a painting ‘for people to walk past’. McCahon described it as a ‘painting and … an environment’.1

On the panels, McCahon rendered numbers from one to ten (or zero to ten) from left to right, mostly with white lettering on black, giving the work that blackboard aesthetic, evoking classrooms of the day. Being from a later generation, however, Numerals also reminds me of those segments from Sesame Street—the American children’s education TV programme ‘brought to you by the letter H and the number 5’—that found endless ways to make counting fun.2 McCahon knows there’s only one way to count from one to ten, but also lots of ways. There are alternative signifiers—you can use Roman numerals, Arabic numerals, and words; you can mix them up; and you can treat them all graphically in varieties of ways. McCahon plays on our expectations, knowing which number comes next but not how he will treat it. McCahon renders his numbers idiosyncratically—with differing degrees of assertiveness and scale—drawing our attention to their more-or-less contingent forms.

Numerals is a jazzy counting exercise. We read its improvised, visually syncopated count against our inner mental metronome. The numbers stutter a bit at first. There’s literally nothing in the first panel—McCahon draws a blank. In the second one, a Roman I and an Arabic 0 (something and nothing) appear together, as if a dyad born in the same originating moment. The third panel is divided in two with a vertical line, with a Roman I on the left and two twos on the right, one Roman, one Arabic. The fourth panel is also divided in half, but horizontally, with an Arabic 2 in the bottom half. In the fifth panel, there’s a sequence: 1, 2, 3. In the sixth panel, there’s an Arabic 3. As Wystan Curnow observed, it takes until the seventh panel, the middle one, to get to four.3 After that, counting hits its stride, becoming regular, each successive panel representing the next number, up to ten.

Numerals marks time, suggesting counting as narrative, painting as a performance. It looks like it could have been painted quite spontaneously, but McCahon said it ‘took months to paint and developed very slowly’.4 He dated the panels separately, all within three months: two are April, nine April to May, one April to June, and one June. The dates bear no relation to panel order.5

Numerals is a classic case of what Professor Green once described as McCahon’s making the format do the work.6 The multipanel structure does much of the heavy lifting, already suggesting seriality—slots into which numbers might fit. McCahon riffs on the shape of the panels: some are divided, horizontally and vertically; treatments of the panel edges suggest a horizon here, a gravestone there; many panels feature contrasting triangular ‘corners’. In the first panel, the lower-left-hand corner (white on black) operates like a sprinter’s starter block, to visually push off against; in the last panel, the top-right corner (black on white) is a visual stopblock. Not only does McCahon count in an eccentric way, the format itself is odd. Two panels (the second and the thirteenth) are wider than the others, so even the underlying grid into which McCahon drops his integers is irregular. These panels mark the beginning and end of the base-ten count: representing zero and one (0 and 1) and ten (10). Rhymes abound.

McCahon’s works endlessly cross reference. Earlier works inform later ones; later ones change our understanding of those that precede them. Numerals certainly looks forward to McCahon’s interest in the stations-of-the-cross theme, which he treats for the first time the following year in two landscape works, The Way of the Cross and the multipanel The Fourteen Stations of the Cross (1966). But it won’t be until the 1970s that numbers become pictorial shorthand for the stations, in works like The Song of the Shining Cuckoo (1974) and the series Teaching Aids (1975) and Rocks in the Sky (1976). But I try to forget that. I like to imagine I’m looking at Numerals when McCahon made it, before his numbers were laden with heavy meaning, like Christ bearing the cross. Instead, I enjoy Numerals for foregrounding the simple pleasures of counting. Numerals is playful McCahon, light McCahon, small-theme-on-an-epic-scale McCahon. It’s a reminder that he wasn’t always and only thinking of the crucifixion.