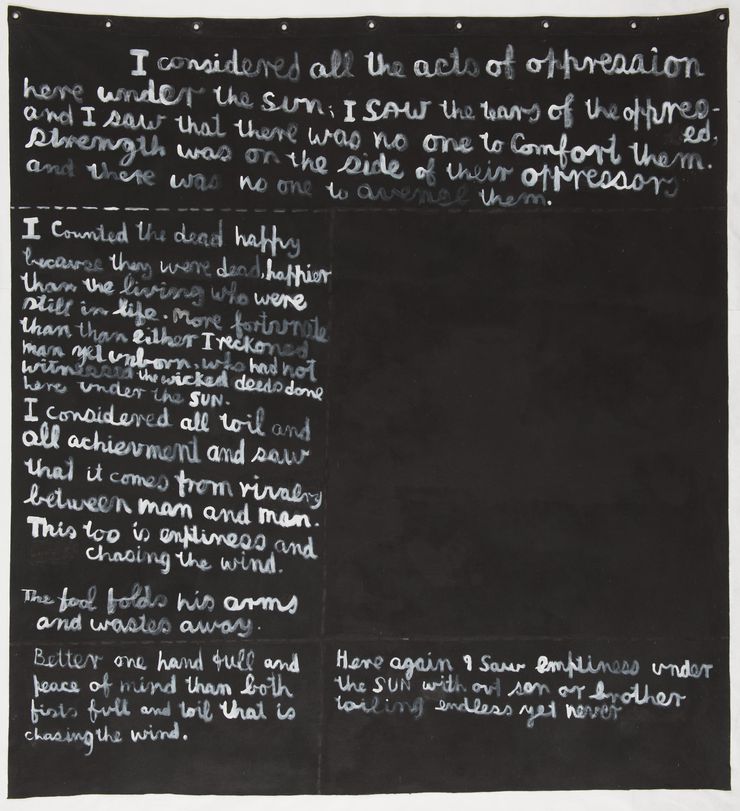

I Considered All the Acts of Oppression

I considered all the acts of oppression, 1981, synthetic polymer paint on unstretched canvas, 1964 x 1810 mm. Courtesy of Dame Jenny Gibbs and McCahon Research and Publication Trust.

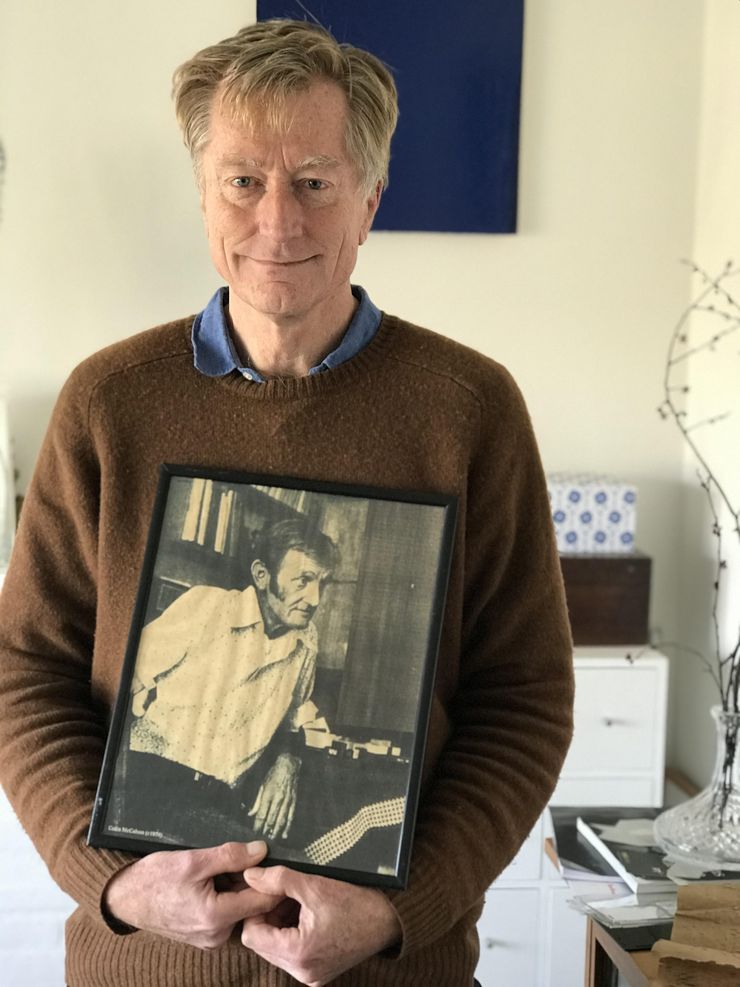

Rex and his McCahon, 2020

Rex Butler

It is 1984, the year of McCahon’s retrospective as part of the Biennale of Sydney. I am in my last year of studying law as part of a combined Arts Law degree at the University of Sydney. I had two years before completed an Honours degree in Art History at the Power Department of Fine Arts, an obviously life-changing experience for me. But as part of my degree I never actually studied contemporary art. I did a Film course, Renaissance Art, French Art and Modern Art, but there was little or no connection drawn in Art History degrees back then between the art you studied and the art you could actually see around you.

I must have wandered back onto the main campus one afternoon from the Law School, maybe hoping to run into an old lecturer. I hated Law and finished it only for my parents. Not finding anyone and not wanting to waste my visit completely, I headed over the University Art Gallery, then housed in an old CSIRO building on City Road. Although I knew nothing of the catastrophe that had befallen the show only a couple of nights before when McCahon had missed his own opening – an episode beautifully chronicled by Martin Edmond in his Dark Night – I do remember an air of obscure disaster hanging over the exhibition. The small wooden gallery with its rickety little rooms and dingy corridors seemed abandoned with only a single distracted attendant at the front desk. I certainly remember being completely alone as I stood in front of McCahon’s paintings mesmerised, wondering what was happening to me. When I stepped back out into the light I felt subtly different, as though everything had irreversibly changed for me.

And the best thing was that I didn’t know anyone I could talk to about it. It was my own secret and it was for me alone to think about. Gradually, of course, I began to realise what had happened to me and what I had been witness to. I used to bore people I knew well enough with how great McCahon was and eventually one long-suffering girlfriend got me this image of McCahon that was reproduced in an Australian art magazine framed for my birthday. It was always the first thing I unpacked in my various student digs while I was undertaking my PhD, where it always sat alone above my desk as some sort of inspiration and measure of the kind of person I was trying to become.

In subsequent years, I received a generous bursary to travel to New Zealand, where I first met McCahon experts Wystan Curnow and Laurence Simmons, the latter of whom I continue to collaborate with. I visited Peter McLeavey’s gallery in Wellington, which I already knew from the installation shots of the shows McCahon had held there. It struck me as something of a sacred space in the midst of the red light district of Cuba Street. Christina Barton later asked me to present one of the Gordon Brown Lectures for Victoria University, where I spoke on McCahon and had the honour of a dinner afterward with McCahon’s great biographer after whom the lecture series is named. On still later trips to New Zealand, I have cried at McCahon’s paintings based on the dog poems of his friend John Caselberg at the National Library, visited the extraordinary collection of Ron O’Reilly’s son and of course wandered bewitched around the McCahon House in Titirangi, imagining the ghosts of Anne and Colin McCahon and children.

I still continue to write and think about McCahon. That experience in front of his work all those years ago changed me irrevocably. The world looked different after I came out than when I went in. I am considerably older now than the McCahon I’m holding in my hands, but I have lived much of my life in his presence. (The photo is no longer above my desk in a crowded house, but is one of the precious keepsakes I keep in a box in the garage) I am currently reading as part of a long-running academic exercise American philosopher Stanley Cavell’s This New Yet Unapproachable America, a book in part on the great American Transcendentalist philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson. Cavell writes of Emerson’s essay ‘Experience’ there:

I would like to say that Emerson’s ‘Experience’ announces and provides the conditions under which an Emerson essay can be experienced – the conditions of its own possibility.

I think that this is true of McCahon as well: his work teaches us how to read it. The most recent thing I wrote on McCahon was a little while ago for an online blog I am involved with called Memo Review. I begin by meditating on the fate of the small McCahon exhibition currently on at the National Gallery of Victoria and then go on to draw a connection – hopefully not too tenuous – between McCahon’s so-called Last Painting, I Considered All the Acts of Oppression (1981) and the current Black Lives Matter movement. In many ways, I see the world through McCahon, and if he teaches us how to understand him he also teaches us how to understand the world.

Memo Review, 22 August 2020

Over the past few weeks, I’ve been pondering the ironic fate of one of my favourite artists, now in total lockdown. I keep on thinking of the sadly unvisited Colin McCahon show at the National Gallery of Victoria, which includes one of his so-called Last Paintings, I applied my mind (1980–2). There it is hanging on the wall, facing outward, unseen. Its poignant message, taken from chapters 7 and 9 of the Book of Ecclesiastes, remains unread in the empty mausoleum-like room it is housed in, silent but for the occasional footfall of the security guards ensuring it hasn’t been stolen.

I say ironic fate because a number of the Last Paintings spent several years in McCahon’s studio waiting for their creator to die before they could be lifted up and taken away. McCahon, before definitively abandoning painting due to a combination of disillusionment and a form of dementia brought on by years of heavy drinking, had given express orders that no one was to go into his studio and his paintings were not to be touched. In the heart-rending words of his biographer Gordon Brown, the family knew that he’d given up when he finally allowed a television into the house; and there McCahon sat slumped before its screen for the last five years of his life, gazing bewilderedly out from the photographs taken of him as his fame grew, various grandchildren crawling unnoticedly at his feet.

It is in one of the Last Paintings that we can see the moment McCahon gives up. There on the right-hand side of I considered all the acts of oppression (1980–2), in the middle of all of the white writing, is a black space. It’s said to be where McCahon actually stopped without finishing his last Last Painting. The text again is from Ecclesiastes, chapter 4, in which Solomon in his old age reflects upon the hardships and difficulties of living with others. These are the words from verse 1 that McCahon reproduces at the top of his painting: “I considered al the acts of oppression here under the sun; I saw the tears of the oppressed, and I saw that there was no one to comfort them. Strength was on the side of their oppressors, and there was no one to avenge them”. And here is some of what McCahon reproduces below: “I counted the dead happy because they were dead, happier than the living who were still in life. More fortunate than either I reckoned man yet unborn, who had not witnessed the wicked deeds here under the sun”.

It is McCahon lamenting through the medium of his appropriated religious text the injustices of the world, but also we might say the injustices he felt had been meted out to him, although the irony is that the painting ended up selling for a record sum to a prominent New Zealand art patron after his death, just as another from the series, Is there anything of which one can say, Look, this is new? (1980–2), ended up in the top-floor office of the Chairperson of the Bank of New Zealand in Wellington as part of their corporate art collection.

But there on the right-hand side is literally where life crosses over into art: it is where McCahon’s life enters into the painting and the painting speaks of McCahon’s life. It is where the painting opens itself up to the world and the world enters the painting. And it is how McCahon’s painting lives on: because in opening itself up to the outside, it at once acknowledges its contingency and decides or determines its own fate. It is the extraordinary paradox of all of McCahon’s work: that in emptying itself of all qualities in an act of religious kenosis, it lives on in whatever form it might take.

It is undoubtedly this logic that drives McCahon’s work as it gradually reduces itself from the early green and brown landscapes to the black-and-white hieroglyphs and finally to the unadorned transcriptions of the Bible. It is precisely how the words of God, Jesus and the Apostles live on in the Bible: because they are whatever their listener takes them to be. Famously, McCahon even dramatises this in his great Victory over Death 2 (1970) at the National Gallery of Australia, where if the spectator reads the text closely they will realise that it is they who are being addressed by Christ on the cross, so that they in effect become one of Christ’s Apostles and the way He lives on.

It is this that we see in I considered all the acts of oppression: that black empty void is exactly that moment where McCahon’s life ends and passes out into his art to be seen and taken up in the world. He is there in his work because he is nothing; and his work will live on because it too is nothing, says nothing and is a mere act of authorial transmission.

It is for this reason that great works of art—the greatest of all: Shakespeare, Dostoevsky, the Bible—live on: not because they are a record of eternal human values, but because they are empty, indeed, the emptiest of all. They can be taken to mean anything, which is why so many scholars have been able to write about them for so long and so many cultures have been able to engage with them and make them their own. They are not at all monuments of a particular time and place but temporary demountables permanently open to the future, to events and attitudes that had not even happened at the time they were made, and at which their makers could not even guess.

And I know I shouldn’t—perhaps it is a symptom of a COVID lockdown madness—but I can’t help thinking when I look at that empty expanse of canvas in I considered all the acts of oppression of Black Lives Matter. It is not just the title of McCahon’s work; it is not just the colour of his paint. It is that one of the questions the movement puts is what of the present will live into the future, and the answer is that only what is truly “universal” will do so.

The tearing down of the statues of Confederate generals, of colonial slave traders, the defacing of Captain Cook and the censuring if not censoring of E Phillip Fox’s painting of his landing in 1770—all of these are not exceptions but part of the constant winnowing of history, the doing away with of that which is no longer considered relevant or appropriate. It is what European culture has done to itself and to virtually every other culture of the world for centuries. But still this winnowing will continue with only the “emptiest”, most universal of things surviving. This is why it is wrong not only to hold up a sign saying “White Lives matter” but even a sign saying “All Lives Matter”. It is because people can identify no longer with “All Lives Matter”, but only with “Black Lives Matter”.

This is why Dana Schultz’s portrait of Emmett Till and Marc Quinn’s sculpture of Black Lives Matter protester Jen Reid do not succeed: because both are too particular, because their authors are too present, because their spectators cannot make them their own. It is why one of the most important artistic manifestos of our time—maybe the contemporary equivalent of Kant’s Critique of Judgement—is Elizabeth Alexander’s book of essays The Black Interior (2004), which makes the point that if “blackness” is an identity it is not because it is specific or definite, but because it is universal and yet to be imagined. As she writes: “The black interior is a metaphysical space beyond the black public everyday toward power and wild imagination”.

All art that lives on has something of this “wild imagination”. If it necessarily comes from somewhere and is done by somebody, it also wants to do away with itself by being from nowhere and by no one. It is an art that can be misheard, misremembered, misunderstood and still remain the same. Like McCahon’s I applied my mind, it might lie dead in its marble mausoleum, but will come back to life the first time someone sees it again. (I remember listening a number of years ago to Lebanese scholar Jalal Toufic giving a lecture on Jean-Luc Godard’s appallingly travestied version of Shakespeare’s King Lear, featuring no less than Norman Mailer as Lear and Woody Allen as the Fool, and his point was that Godard was trying to see how far he could distort Shakespeare’s original and still have it remain the “same” play. I also remember him saying—to the nervous gasp of the audience—that Islam is similarly not a single unbroken tradition, but constantly re-imagined and re-interpreted.)

Earlier this week, I went to a conference put on by the Centre of Visual Art as part of Science Week devoted to the now famous photo of a black hole by a team of astronomers working around the world that emerged in April 2019. The conference featured any number of prominent academics, artists and scientists, but by far my favourite presentation was by Katie Bouman, a Caltech-based engineer who helped develop the computer code necessary to produce a visual image based on the data gathered.

Actually, I should correct myself. It is not a black hole that is being imaged, but an “event horizon”: that moment when the gravity of the black hole is so intense that the light of the collapsing star cannot leave and remains trapped, producing a kind of permanent glow or halation around a darkness that is unable to be seen. (In fact, if I was following what Bouman was saying, it is not so much the event horizon we see but the shadow it casts against a background of super-heated gas.)

As usual, the facts and figures are mind-boggling. Galaxy Messier 87 where all this occurred is some 55 million light years away, the black hole weighs six and a half billion times as much as the sun, the gas that the black hole casts its shadow against is thousands of billions of degrees hot. It required a telescope effectively the size of the earth to see what was going on and to see a black hole at that distance is like finding a grain of sand in California while standing in New York.

But the bewitching thing about Bouman’s talk was her account of how the image was actually produced. The problem, she explained, was that there was not quite enough information received through the telescopes, so that scientists had to be very careful not to impute the actual shape of the event horizon as a circle from Einstein’s prediction in his theory of general relativity. To that end, she commissioned four teams from around the world to each make up their own version from what they had and only later got them together to compare.

What we now see is the averaging out of these four different versions to reveal what is common to all. It is not only the perpetual struggle between light and gravity but between all of our various guesses and projections. And undoubtedly further research will provide more information—for, like all good scientists, having pulled this off they are now planning a new and improved series of experiments—successively changing our image of it. But it will still remain the “same” event horizon: that milky glowing cloud shifting but nevertheless remaining fixed across all possible changes.

Maybe if we wanted an artistic comparison—and to think how art is like this—we might think of Ed Ruscha’s paintings of burning museums, in which, like a black hole, we have a kind of permanent stasis between the fire and what it burns, the museum being burnt down and art arising from its ashes. Or, to go back to where we began, we might think of the “black hole” of McCahon’s I considered all the acts of oppression, with those white letters around it like an event horizon. Here too the work is the unchanging residue of all of our projections, all of our calculations, not because it is simply unchanging but because it is its own change. It is only our guess looking up at its dark sky, but as the very emblem of its own end it will still be there hanging on a wall when we are all long gone. Indeed, in the version currently at the National Gallery of Victoria, it already is.