Fourteen Stations of the Cross

The Fourteen Stations of the Cross, 1966, synthetic polymer paint on 14 sheets of paper, 750 x 555 mm. Collection of Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, courtesy McCahon Research and Publication Trust

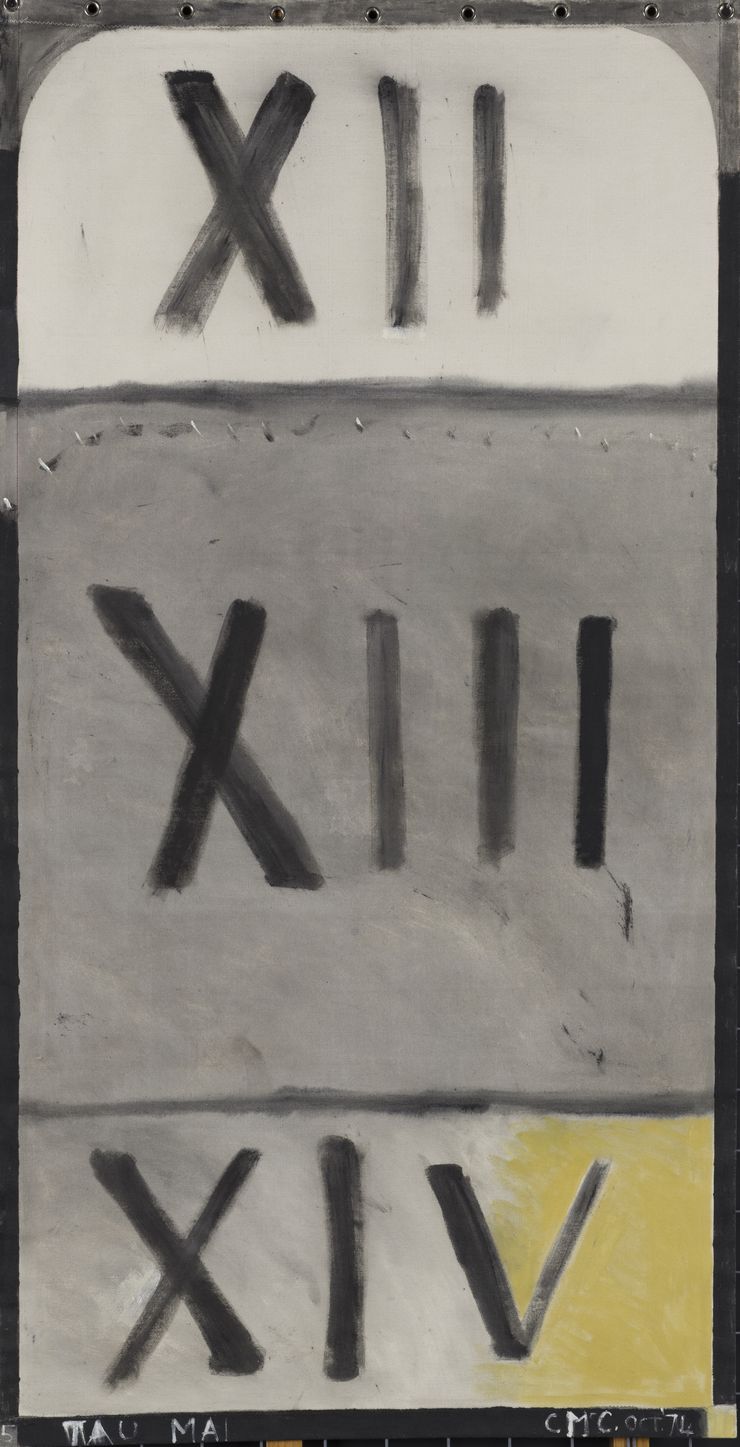

(Work 5 out of 5) The Song of the Shining Cuckoo, 1974, synthetic polymer paint on 5 unstretched canvases 1758 x 903 mm. Colleciton of Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hakena, University of Otago, courtesy McCahon Research and Publication Trust

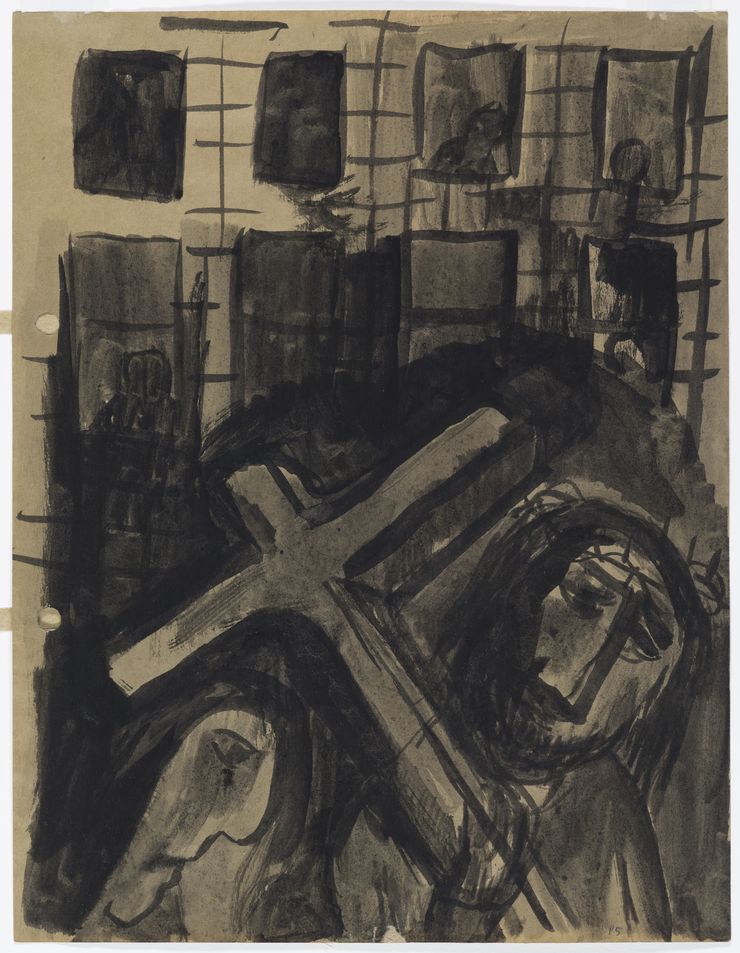

(Work 10 out of 16) Fifteen Drawings for Charles Brasch, 1951-52, brush and ink on brown paper, 260 x 200 mm. Colleciton of Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hakena, University of Otago, courtesy McCahon Research and Publication Trust

Priscilla Pitts

Many years ago, when I was regularly using the Auckland City Art Gallery’s research library, Colin McCahon’s Fourteen Stations of the Cross (1966) was displayed in the short corridor leading to the library. I don’t know how many times I passed it but invariably I stopped to look searchingly at these fourteen relatively small images painted in broad, uneven, horizontal bands with the occasional single (mostly diagonal) brush stroke. Their palette is sombre – and familiar to those who know McCahon’s work: grey, black, buff with a few areas of soft yellow.

I’d been taught by McCahon in my one year at Elam (1967) and I still remember the day he took a group of us down to Victoria Park in Freemans Bay to draw the gasworks. His telling me to think about the relationships of diagonal, horizontal and vertical elements in these large industrial structures and to be aware of the contrast between the light of even an overcast sky and the relative darkness of everything else we could see frequently comes to mind when I look at or think of his work – and nowhere more so than in the Fourteen Stations. As in so many of his paintings these elements take him – and us – far beyond the physical world into the realms of the spiritual and metaphysical.

The Fourteen Stations of the Cross are a common subject in the iconography and devotions of the Christian church; they map the journey, both physical and emotional, of Christ’s progress to the site of his crucifixion, his death and the disposal of his body. Many images of the various stations have been made over the centuries, re-enactments are staged (the most famous of them at Oberammergau) and pilgrims still walk the Via Dolorosa in Jerusalem. A knowledge of this aspect of the Christian story certainly helps one’s understanding of what I believe McCahon wants to convey in this work and he comes to our aid with a brief description at the lower edge of each image:

- Christ is condemned to death

- The Cross is laid upon Him

- His first fall

- He meets His Blessed Mother

- Simon is made to bear the Cross

- His face is wiped by Veronica

- His second fall

- He meets the women of Jerusalem

- His third fall

- He is stripped of His garments

- His crucifixion

- His death on the Cross

- His Body is taken down from the Cross

- He is laid in the tomb

A calm sense of inevitability pervades this work, quite unlike the sceptical (in McCahon’s hands, anguished) questioning of his earlier Elias paintings1 or the raw intensity of the Rouault-like 15 Drawings (December ’51 to May ’52) which include ‘The Cup’, girdled with Christ’s crown of thorns, the howling mob (‘give us Jesus’) and Christ’s agonised face beneath the weight of the cross. Yet he manages, with the most economical of means, to freight these fourteen images with emotional import.

The journey to the cross, perhaps more than any other aspect of the Christian story, is eloquent of Christ’s human frailty rather than his divinity. His body is broken by the material weight of the cross, his heart oppressed by the apprehension of the physical agony of the crucifixion. Almost certainly he is racked with doubt about what lies on the other side of death, unsure as to whether his heavenly Father will truly come to save him. And along the way it is human love that gives him succour: his encounters with his mother Mary and with the women of Jerusalem who weep for him, with Veronica who uses her veil to wipe the sweat and blood from his face. Even the Roman soldiers who compel Simon of Cyrene to carry the cross in Christ’s stead following his first fall relieve him of that cruel burden. In each of the images devoted to these four moments of compassion or release, the louring darkness is relieved by a luminous yellow sky or foreground. And although the Fourteen Stations do not include Christ’s rising from the dead, in McCahon’s final image (‘He is placed in the tomb’) there is a faint lightening of the sky, heralding the dawn of the hope offered to all Christians by the resurrection.

That possibility of salvation was something McCahon strove to convey in his work. He wrote to Toss Woollaston about his painting The Good Shepherd that it was ‘almost destroyed now … I feel there must have been something dishonest about its beginnings. It was only death & hell & no resurrection.’2 The following year he said of The Three Marys at the Tomb (1950) ‘My three women at the tomb with flying angel is really something to look at. Am still adding & correcting & at the same time in the midst of a large blue version of the same subject. I do feel these 2 have something of redemption & not only the fall. If so it is an advance.’3

Accustomed as we are to McCahon’s simplified renditions of landscape, we, of course, read these fourteen images in those terms. Here are not the geographically specific parched Nelson hills, the silhouette of Mount Martha in Practical Religion: the resurrection of Lazarus showing Mount Martha (1969-70), or the Auckland landforms in The Way of the Cross (1966). Rather, he depicts generalised, even archetypal, features such as those in paintings like Tomorrow will be the same but not as this is (1957), Small Landscape with Domed Hill (1966) and the The Waterfall Series (1965).

And what of those bleached brushstrokes slicing across the dark land? Two of them (in ‘His crucifixion’ and ‘His death on the Cross’) closely resemble the downward fall in certain of the simplest Waterfall paintings while others suggest an uphill path.

Then there is the element of time in so many of McCahon’s landscapes: the episodic structure of Six Days in Nelson and Canterbury (1950) and the picturing of time passing in Takaka Day and Night (1948); the landscapes he invites us to walk past (I always want to say ‘through’ as I sense that McCahon wants us to be in them as he was), such as the Northland Panels (1958), Walk (Series C) (1973) and The Song of the Shining Cuckoo (1974). The Fourteen Stations gives us all of this and more. It offers a pilgrimage, a metaphor for the human journey through difficulty and pain with always the promise of salvation and joy on the other side of such travail. Though it seems that hope of salvation deserted McCahon towards the end of his life, it is ineluctably present in this particular work.

For McCahon the number fourteen became deeply significant and it dominates much of his work through the 1970s. Though I’m aware of only one other work (The Way of the Cross4) that explicitly traces the Fourteen Stations of the Cross, the numbers one to fourteen are present in key paintings, including The Song of the Shining Cuckoo and the series Rocks in the Sky (1976) and Teaching Aids (1974). In Walk (Series C) each 'frame’ is numbered one to fourteen; these are not views but stages on the journey. A Tau cross dominates the first ‘stage’ and a fraction of the cross frames the penultimate one, the work as a whole bringing the Way of the Cross, the Via Dolorosa, into the beach environment so familiar to New Zealanders.5

Some commentators seem to have found McCahon’s obsession (for it is that) with Christianity hard to swallow and the jury will always be out on the question of the artist’s relationship with that brand of religion. McCahon himself apparently stated ‘I could never call myself a Christian’6 yet I can’t help but wonder whether his use of the Christian story really is simply a metaphor for the human enterprise of struggle, doubt, joy, hopefulness and despair, or something more. McCahon’s son William writes that his father’s ‘entire oeuvre is the narrative of his life of spiritual and emotional discovery’7 and also of ‘… a commitment to Christianity as a vehicle for his spiritual thought’ and McCahon as a ‘homeless Christian’.8 Each of us will come to The Fourteen Stations of the Cross with our own opinions or beliefs. I look at the work with the eye of an art historian and art commentator; but that does not explain why, more than thirty years ago, this work took hold of my heart and has never let go.

[1] The Biblical texts on which the Elias paintings draw arise from a misinterpretation of the Aramaic words ‘Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani’, meaning ‘My God, my God, why has thou forsaken me’ which Christ cried out from the cross. Onlookers, some of whom had earlier jeered at the self-proclaimed Son of God’s apparent inability to save himself, mistakenly thought he was calling on the prophet and miracle worker Elias to save him. McCahon surely knew of this mis-translation and I imagine was aware of the ironic parallel of the misunderstanding by many viewers of his own work and intentions.

[2] Colin McCahon to Toss Woollaston, undated [December 1949], cited in Peter Simpson, Colin McCahon: There is Only One Direction, Vol. 1 1919-1959, Auckland University Press, Auckland 2019, p.135.

[3] Colin McCahon, letter to Ron O’Reilly, 15 February 1950, ibid, p.158.

[4] This work was commissioned for the chapel of the Convent of Our Lady of the Missions in Auckland. It is now housed at the Auckland Art Gallery.

[5] In Gordon H Brown, Colin McCahon: Artist, AH & AW Reed Ltd, Wellington, 1984, the work is titled Walk (Beach Walk Series C).

[6] Cited in Gordon H Brown, ibid, p. 151.

[7] William McCahon ‘A Letter Home’, Marja Bloem and Martin Browne, Colin McCahon: A Question of Faith, Craig Potton Publishing, Nelson, and the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 2002, pp 29-37 [29].

[8] Ibid, p 31.