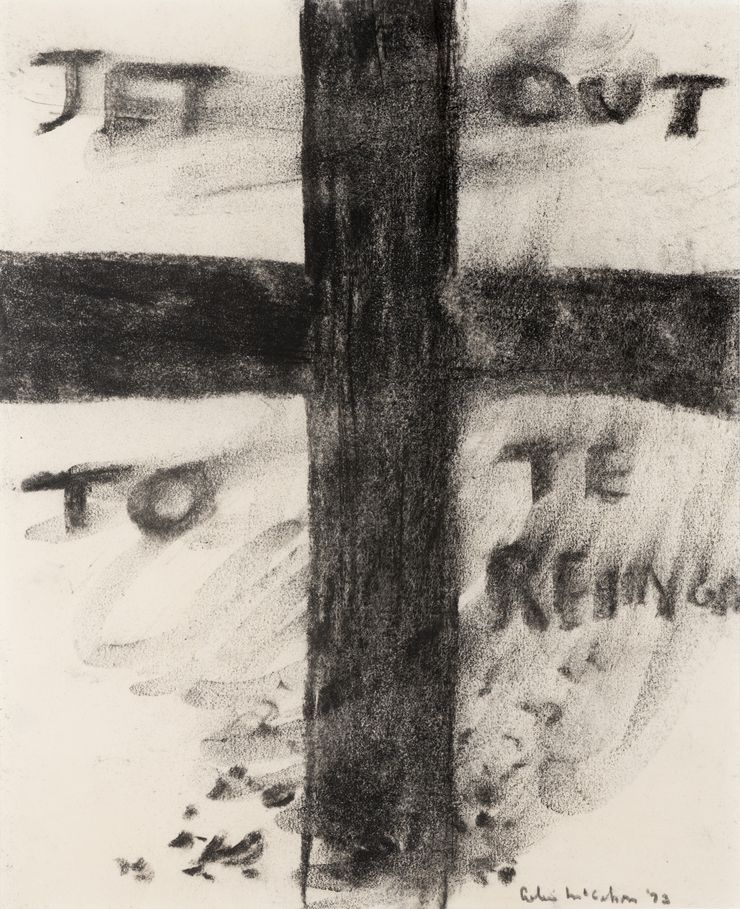

Jet out to Te Reinga

Colin McCahon, Jet out to Te Reinga, 1973, charcoal on paper, 338 x 273 mm. Private collection, courtesy McCahon Research and Publication Trust.

The cover of Peter Simpson's forthcoming book on McCahon There is Only One Direction. To be published October 2019.

Peter Simpson

I first wrote about the work of Colin McCahon 25 years ago, in a 1995 article called ‘Candles in a Dark Room: James K. Baxter and Colin McCahon’; later that year I curated an exhibition of the same name at Auckland Art Gallery’s McCahon Room. Although the charcoal drawing Jet out to Te Reinga (1973) was not mentioned in that essay, it might well have been, since it implicitly alludes to Baxter’s death.

My point of entry to writing about McCahon was through my specialist interest in New Zealand poetry, a focus of my university teaching in Christchurch and Auckland. Indeed, for a decade or so most of my writing about McCahon concerned his relationships and collaborations with New Zealand poets and their work. The admiration between McCahon and poets was mutual; he was an avid reader of poetry (R.A.K. Mason, Robin Hyde, Charles Brasch, Baxter, John Caselberg, Peter Hooper, Gerard Manley Hopkins), and poets were always among his greatest admirers. He once wrote: ‘Poetry, before painting, is my friend. The one without the other can’t exist.’1

Following Baxter my focus was on McCahon’s relationship with Caselberg (who provided the texts for the Van Gogh lithographs, The Wake and other works), an interest which led to the touring exhibition Answering Hark: Caselberg/McCahon; Poet/Painter (Hocken Library, 1999), followed by a book of similar name (Craig Potton, 2001). Much later, another painter-poet connection I explored was his many-sided relationship with the poet Brasch, as documented in Patron and Painter: Charles Brasch and Colin McCahon (Hocken Collections, 2010), based on my 2009 Hocken Lecture.

The first time I stepped beyond the painter/poet axis was in 2006-007 with the exhibition and book, Colin McCahon: The Titirangi Years 1953-1959 (Auckland University Press); the exhibition was shown at Lopdell House to mark the opening of the McCahon House and Residency, while the book followed a year later. Here the focus was not on relationships with poets as previously but on a specific period – the seven highly productive years he lived and worked at French Bay, Titirangi. Later, in a chapter of Bloomsbury South: The Arts in Christchurch 1933-53 (AUP, 2016) I examined the five years McCahon had lived and worked in Christchurch, 1948-53 – another period study – and specifically again his friendship with Baxter in that time and place.

As the 2019 McCahon centenary approached I chose to greatly expand my approach by undertaking a comprehensive study of his whole career, not attempted in book form since Gordon H. Brown’s Colin McCahon: Artist in 1984 (revised 1993). With the support of AUP and Creative New Zealand, I wrote what turned out to be a two-volume book: Colin McCahon: There is Only One Direction, Volume One 1919-1959 (2019) and Colin McCahon: Is this the Promised Land?, Volume Two 1960-1987 (2020), which together cover his 45 year career from beginning to end.

Over 25 years, therefore, my approach to McCahon has evolved from the narrowly specific to the broadly comprehensive, a process through which my esteem for his achievement as an artist has grown as my knowledge and understanding of his life and work have expanded. Over the same period I have written about many other artists and writers – including Allen Curnow, Kendrick Smithyman, Leo Bensemann, Peter Peryer, Ursula Bethell and Charles Brasch – but my writing on McCahon has been the most sustained and extensive of my career.

Given such a background, to settle on one particular work out of the 2000 or so he made as my contribution to McCahon 100 was not easy. My choice eventually fell on a drawing from 1973 which is coincidentally closely linked through the connection to Baxter to my first McCahon project as writer and curator quarter of a century ago, Jet Out to Te Reinga (charcoal, 1973).

Most of the Easter 1973 drawings to which Jet out to Te Reinga belongs are connected with Baxter’s death the previous year. McCahon and Baxter had been close friends since they met in Dunedin in 1946. Soon afterwards McCahon painted A candle in a dark room (1947) as a symbolic portrait of the poet, while in 1948 Baxter wrote ‘Salvation Army Aesthete…?’, an important early essay about McCahon. Later, however, their friendship became strained when Baxter in his barefoot radical phase unkindly accused McCahon of being bourgeois because he worked at a university art school. A serious breach between them occurred and, unfortunately, they were still unreconciled when Baxter suddenly died at 46 in October 1972. McCahon immediately threw himself into a fever of activities – including paintings, drawings and theatre productions – honouring Baxter’s memory, trying, perhaps, to expiate his grief and guilt.

First came a small painting, Jim passes the northern beaches (1972), which associated Baxter’s death with Maori mythology. In 1973 McCahon began a major series of paintings, starting with A handkerchief for St Veronica (1973), which combined thoughts about Baxter’s death with the Stations of the Cross (Baxter was a convert to Catholicism), together with the landscape of the long beach at Muriwai, and the myth of the spirit’s passage after death up the western beaches to the northern tip of the island, Cape Reinga – the leaping off point.

McCahon spent Easter weekend of 1973 at Muriwai (where he had a studio) making dozens of drawings, using charcoal, pencil, conté or crayons on paper. He wrote to Peter McLeavey: ‘I’m sending you 33 drawings… There are another 30 or so on other topics all coming from this Easter at Muriwai….Somewhere in these is the direction I’m going. The comic book.’2 Eventually there were about 80 drawings, many of which depict a jet plane taking off over the ocean as signified by two crossed diagonal lines looking somewhat like a flying cross. The whole series was called Jet Out.

Easter is a time when Christians are encouraged to think of death and resurrection. The flying cross symbolises both; as a cross it signifies crucifixion and death, but as a jet plane it also symbolises resurrection, the ascent from death into heaven. Direct evidence for the fact that Baxter was the implicit subject of the Easter drawings comes from McCahon’s letters about the paintings (Series A, B, C and D) exhibited with the Easter drawings in Jet Out from Muriwai at Barry Lett Galleries, Auckland, in August 1973 and An Exhibition of Recent Works by Colin McCahon at Peter McLeavey Gallery, Wellington, in September. He wrote to the Dunedin painter Patricia France: ‘I’ve been painting a big series on J. K. Baxter. 14 Panels – all sizes: 'Stations of the Cross’ from black & white to violet to yellow, huge & rough & beautiful, I think…’3 And to McLeavey he wrote: ‘Your lot [Series C, Walk] have numerals painted on them – are really Stations of the Cross & are painted in memory of Baxter… a friend who now – in spirit – has walked this same beach…The Christian “walk” and the Māori “walk” have a lot in common.’4

Jet out to Te Reinga is one of only two Jet Out drawings showing the cross in the conventional upright position rather than in diagonal flight. Also, instead of being a cartoon-like diagram of simple crossed lines, in this drawing the cross, drawn in dense black charcoal, is weighty, solid, substantial, monumental. The notion of spiritual journeying is conveyed mostly by the words in block capitals JET/OUT/TO/TE REINGA distributed among the four quadrants formed by the verticalsand horizontals of the cross. The letters are deliberately smudged, probably with a thumb, as if to suggest a sense of urgent movement.

Dense with connotations Jet out to Te Reinga is one of McCahon’s masterpieces in the drawing medium.

[1] Colin McCahon to Malcolm Ross, 27 March 1973, quoted in Peter Simpson, Colin McCahon: Is this the Promised Land? Volume Two, 1960-1987. Auckland:Auckland University Press, 2020 (forthcoming).

[2] Colin McCahon to Peter McLeavey, 1 May 1973, quoted in Simpson, op. cit.

[3] Colin McCahon to Patricia France, August 8 1973, quoted in Simpson, op. cit.

[4] Colin McCahon to Peter McLeavey, August 16, 1973, quoted in Simpson op. cit.