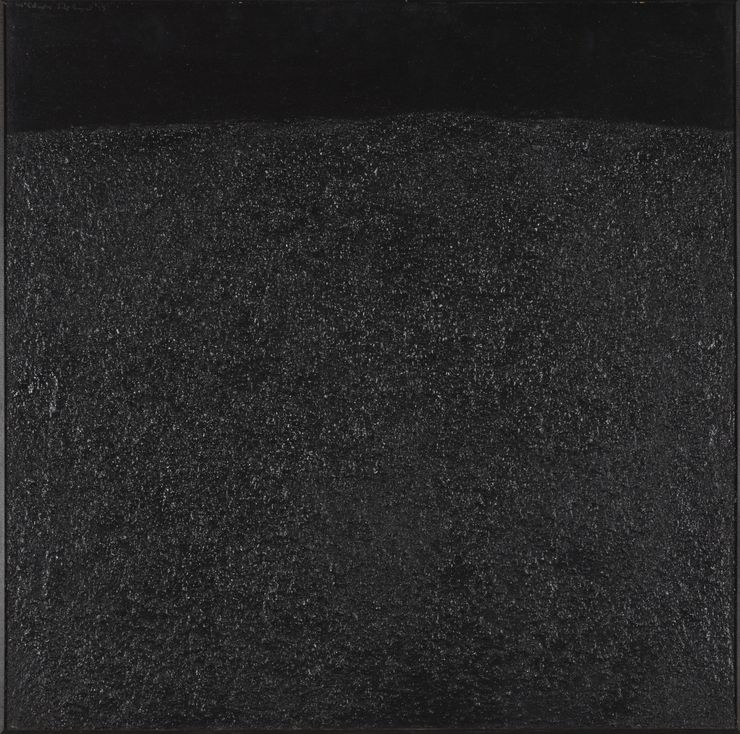

Black Landscape

Colin McCahon, Black Landscape, 1965, PVA paint and sawdust on hardboard. Purchased 1976 with Special Government Grant, Collection of Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (1976-0040-4), Courtesy of the Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust.

Buster Black, Mountain 1, 1963-64, oil and sand on hardboard. Purchased 1992 with New Zealand Lottery Grants Board funds, Collection of Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (1992-0008-1)

Megan Tamati-Quennell

Just a good painter

For McCahon100, I chose to focus on Colin McCahon’s Black Landscape, 1965 bought for the National Art Gallery collection, the genesis of the Te Papa art collection, in 1976. McCahon’s painting is an abstracted landscape, that I like to think of as a moonscape. McCahon restricts himself to the colour black completely, but contrast and dimension are featured in the work through a textured paint surface made from sawdust mixed into polyvinyl acetate or PVA paint. I chose Black Landscape, 1965, stunning in its restrained but visceral aesthetic, because the influence of Māori painter Buster Black or Buster Pihama (also known as John Pihama) can be seen clearly in this work.

Buster Black, who was of Ngāti Maniapoto and Ngāti Rangi descent, attended art classes taught by McCahon at Auckland City Art Gallery in 1956. The relationship between Buster Black and McCahon was as student and teacher, but they also developed a strong friendship.

Through conversations that ranged across Christianity, music and painting, the two men became close friends and spiritual confidants, pupil and teacher influencing each other.1

When Robert Leonard and Wystan Curnow curated the critical exhibition that looked at McCahon’s ‘evolving engagement with Māori themes and subjects,’2 at City Gallery, Wellington in 2017—Colin McCahon: On Going Out with the Tide—Buster Black was mentioned in their exhibition text, but his work was not included in the show and his influence not explored within the exhibition. It is often like that with Buster Black. Justin Paton in his book McCahon Country, credits Buster with intensifying the ‘earthing’3 of McCahon’s paintings in the 1960s and others recognise Buster’s influence on a whole new direction for McCahon—his waterfall series from 1964, that feature a symbolic white curve of water through a dark background.

The waterfalls started flowing in 1964 … They grew out of William Hodges’ paintings on loan to the Auckland City Art Gallery from the Admiralty, London. [Hodges was the official painter on Cook’s second voyage in 1772–75.] … 4

Acknowledgment is due to another artist for his influence on McCahon’s new direction, Buster Black…

He is known and cited as an important influence on McCahon’s work and practice, but we still know very little about Buster and there has never been a focused exhibition of his work.

In the 1960s, Buster began creating a series of ‘night paintings’, in which the images feature the tiny gridded street lights of urban centres, cities and towns, picked out of the darkness. He also created images, again primarily using a monochromatic colour palette, evocative of his spiritual relationship with the land, including a vision he experienced of Mount Ngauruhoe crying. Buster wanted his work to be a conduit for the communication of the land itself. McCahon was said to be ‘struck by the dramatic visuality of white light on black’5 in Buster’s images, and also with his use of fine particles of glass, sand and wood he used in the body of his paintings. McCahon later adopted Buster’s technique of adding texture to his work, adding sawdust to his paint like he has in Black Landscape. Auckland painting conservator Sarah Hillary who interviewed Buster in 1998, said Buster liked to add what he described as ‘tortured paint skins’; glass and sand to create a textured surface that he and McCahon referred to as a ‘jumping surface.’6

One of the reasons I believe Buster gets missed is he worked as ‘a painter’ rather than a ‘Māori painter’ as McCahon outlined in a letter to John Caselberg in 1968, that is held in the Hocken Library in Dunedin and which Leonard and Curnow in their City Gallery, Wellington show presented as a facsimile. An excerpt of McCahon’s 1968 letter reads:

Māori painters’ as Ralph Hotere & Buster deny being—only painters, are being themselves, now in time—Arnold Wilson—to a great extent Para Matchitt don’t know yet where they stand—New Zealand painters or ‘Māori’ painters …

… Ralph is just a good painter—Buster is just a good painter—Rita Angus is just a good painter—Woollaston is just a good painter—Para Matchitt is trying to be a Māori painter—Selwyn Muru is trying to be a Māori painter—Arnold Wilson is trying to be a Māori sculptor—Molly Macalister is a good sculptor … 7

Buster was however, similar to other Māori modernists working in the 1950s and 60s. There was no set way of being a Māori modernist; no set criteria, fixed techniques or stylistic affinities that needed to be adhered to. The subject matter the Māori modernists worked with was also diverse. Their work did not need to be overtly Māori or to make reference to customary Māori art or culture to be considered Māori modernism. The only shared approach of the Māori modernists, much like contemporary Māori artists today, was a commitment to contemporary art. The Māori modernists saw their work as part of the contemporary art of the period and as sharing many of the same concerns as their non-Māori contemporaries.

Buster also gets missed I believe, because his focus was on the land, a subject not seen overtly as Māori. Yet, it can be argued, that land or whenua is the ultimate Māori subject. That land has always been depicted as central to Māori art and thought, like the mountain that features in the head of Taranaki whakairo or carvings, and that land and connection to place is essential to a Māori ontology and to a Māori world view. Similarly, it can be said that landscape, and our relationship to it, was of central importance to McCahon and a key subject within his practice. Ideas about land and spirituality common to both Buster Black and Colin McCahon, to me, are the bigger connection between their work, more than the surface treatments and painting techniques they shared and that are visible in their individual practice.

McCahon’s fascination with earth as a medium went deeper than technique and texture. For a religious painter seeking new ways to be at home, Māori spirituality—based, as Black’s vision illuminates, in a connectedness to land—exerted a powerful attraction.8

McCahon, as Justin Paton has said, is our most ‘soulful artist’ and as an artist, he wanted to know, as artist Michael Parekowhai said, ‘what we should believe in and where we belong.’9

This small piece of writing about Colin McCahon, Black Landscape and Buster Black, was intended to be a dual conversation with Finn McCahon-Jones, who has been researching Buster Black’s work and practice. That was unable to happen in this instance, but I wanted to acknowledge Finn and the work he has been undertaking.

Nga mihi kia koe Finn, kia hora te marino, kia whakapapa pounamu te moana, kia tere te kārohirohi i mua tō huarahi.

[1] http://www.mccahon.co.nz/sites/all/files/Q_of_F-Part3.pdf, p.202 [accessed 16 July 2020]

[2] http://citygallery.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/McCahonVersion2.pdf [accessed 16 July 2020]

[3] Justin Paton, McCahon Country, Penguin Random House New Zealand & Auckland Art Gallery, Toi o Tamaki, 2019, p.238

[4] http://www.mccahon.co.nz/sites/all/files/Q_of_F-Part3.pdf, p.202 [accessed 16 July 2020]

[5] ibid

[6] https://issuu.com/aucklandartgallery/docs/working-towards-meaning-the-restoration-of-colin-m [accessed 16 July 2020]

[7] http://citygallery.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/McCahonVersion2.pdf [accessed 16 July 2020]

[8] Justin Paton, McCahon Country, Penguin Random House New Zealand & Auckland Art Gallery, Toi o Tamaki, 2019, p.239

[9] Justin Paton, McCahon Country, Penguin Random House New Zealand & Auckland Art Gallery, Toi o Tamaki, 2019, p.12

Purchase a print publication of McCahon 100 here.