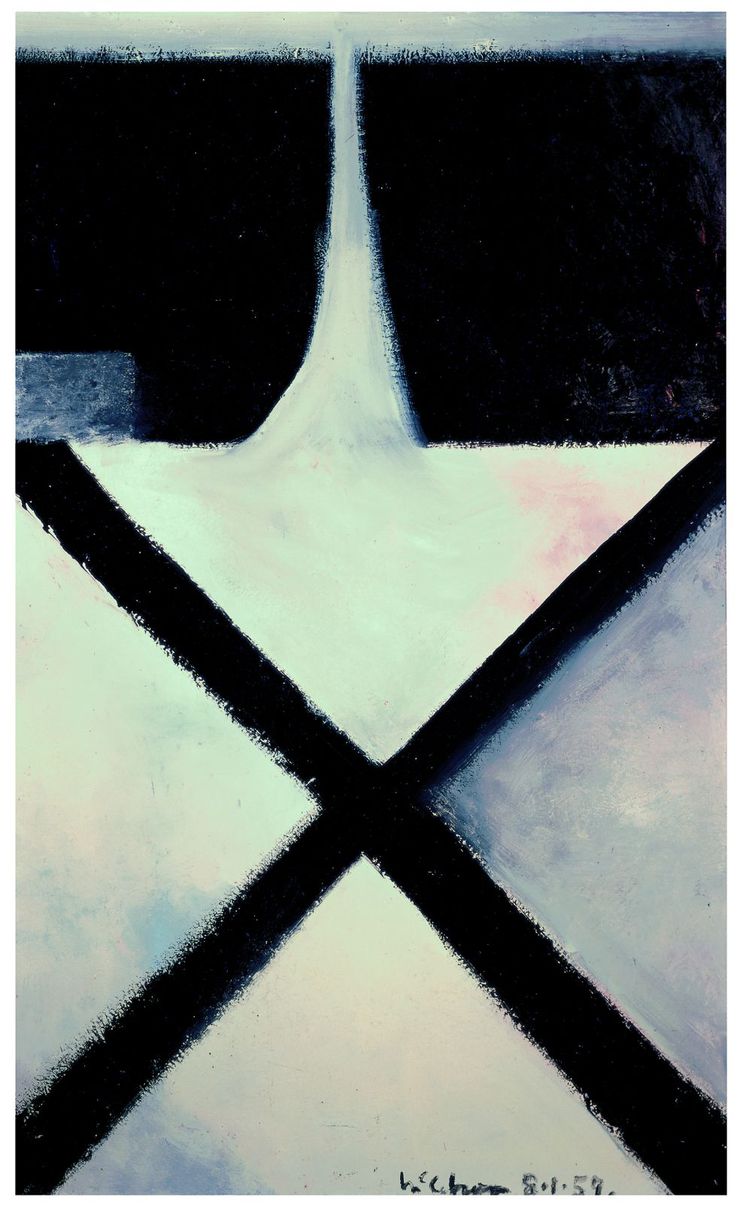

Cross (1959)

Colin McCahon, Cross, 1959, Enamel and hardboard, 1219x762mm. Collection of Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, on loan from a private collection. Courtesy McCahon Research and Publication Trust.

The Buddhas of the Six Realms: Atagomachi, Iiyama City, Nagano Prefecture

Martin Edmond

Cross (1959) was reproduced on the cover of my first book, The Autobiography of my Father (AUP, 1992) although I don’t recall precisely how that happened. The work, from a private collection, was at the time on loan to the University of Auckland; someone, perhaps AUP Director Elizabeth Caffin, told me about it and one day I went to see it hanging on the wall in an empty seminar room in the English Department. I remember how desolate and abandoned that room was and also how the painting looked, the way paintings sometimes do, both humble and resplendent. The board it was painted upon had warped a little and I could see how it was made out of mundane materials, while at the same time transforming those materials into something ineffable.

Cross (1959) is one of a group of related paintings from the late 1950s. They include Painting (1958), which was a joint winner of the Hay’s Art Competition in 1960; Tomorrow will be the same but not as this is (1958-9); and A landscape—Fragments of a cross (1959). These predominantly black and white abstracted landscapes lead into the Gate series of the early 1960s; they look like outliers of a main range which has not yet been explored: there are hidden valleys and unscaled peaks in the black hinterland you see towards the top of the picture. There’s also the tenderness of colour in the four triangular sections demarcated by the saltire, the St Andrew’s cross, below: the subtle pinks and greyish blues coming through the whites and the creams.

I also like that there is a date on the painting: 8.1.59, which was Elvis Presley’s 24th birthday and also the day before my sister Rachel’s fifth birthday; and a week and a day before my own seventh birthday. The Elvis connection isn’t random: I’ve always called the photograph of my father in his New Zealand Air Force uniform, taken just before he went away to war in 1943, the Elvis picture because in it he looks so darkly handsome, so charming and so full of promise that it’s heart-breaking to consider what happened to him in later years: which of course you could say about Elvis too. And McCahon.

There are other parallels. McCahon and his wife Anne, my father and mother, were part of the same set in Dunedin after the war, when Dad’s best friend from Training College and Air Force days, Noel Parsloe, married Colin’s older sister Beatrice. That’s why I grew up with one of the children’s paintings Anne and Colin made in 1944 on my bedroom wall: Bea gave it to my parents when my eldest sister Virginia was born in 1947. There are vaguer connections: in those post-war years many people of their cohort, in a spirit of youthful idealism, not uninformed by the terrible things they had experienced or heard about during the war, set out to remake the world along better and fairer lines.

Colin’s method was painting and my father’s was teaching; and you’d have to say that both, in their separate ways, did make a difference; at the same time, each bore a personal cost which is more or less incalculable. It was the mystery of my father’s decline from a state of energetic optimism in the 1950s into alcoholism and despair in the 1960s and subsequently which made me want to write about him. McCahon, too, tasted despair and tried to ease it through the use of alcohol; in both cases, sherry was their drink of choice.

Dad was inclined to repeat that old chestnut, the Serenity Prayer, which he probably picked up at an AA meeting. God grant me the serenity / To accept the things I cannot change / Courage to change the things I can / And the wisdom to know the difference. I don’t know if McCahon knew that prayer too but when I look at the black cross in this painting, which seems at once an interdiction against, and a passage through into, the blessed land, I think he must have. In the same way the fall of light from above in Cross (1959), which McCahon picked up in the waterfall paintings of the 1960s, offers another pathway to serenity.

Contemporary with those waterfalls are some works which use a sentence derived from Jōdo Shinshū, Shin Buddhism, also known as Pure Land Buddhism: As there is a constant flow of light we are born into the pure land. One of the enlightened beings of Shin Buddhism, Jizō Bosatsu, resiled from the attainment of Buddhahood until all of those trapped in the various hells are freed and can also enter the pure land. On a recent visit to Japan, my first but not my last, I saw many shrines to Jizō, who is usually depicted as a Buddhist monk. Those I encountered featured a life sized statue facing a row of six smaller statues, representing the six realms: Deva, Human, Asura, Animal, Hungry Ghost and Hell.

Jizō is the guardian of children, dead or alive, and the patron of aborted foetuses. You see statues of him at or near cemeteries and at roadside stations: he looks after travellers too. Somehow this painting, despite its Christian iconography, represents the compassion shown to the poor, the downtrodden, the suffering and the bereft in other religions too; and its presence on the cover of my book has become for me a lesson in the way of compassion as taught by McCahon as much as the monk Jizō; and indeed by my father too, who as a teacher was always alive to the possibility of redemption, secular rather than divine, through the furnishing of education to those disadvantaged among us.