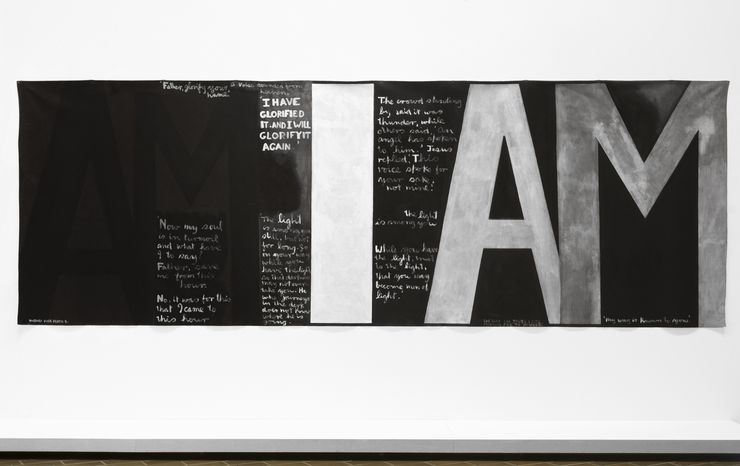

Victory over death 2

Colin McCahon, Victory over death 2, Synthetic polymer paint 1970. Collection National Gallery of Australia, gift of the New Zealand Government 1978, courtesy McCahon Research and Publication Trust

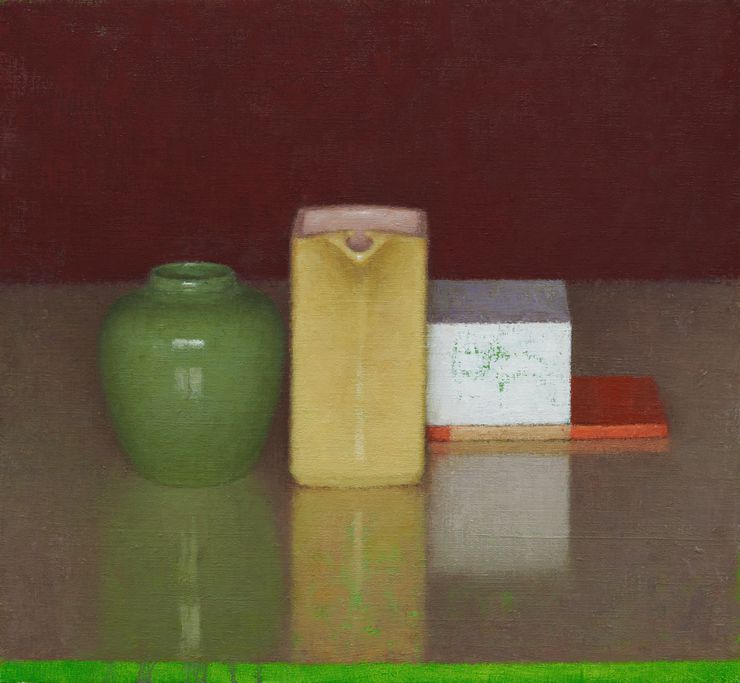

Jude Rae, SL413, 2020, oil on linen 1220mm x 1370mm.

Colin McCahon, The lark's song, 1969, synthetic polymer paint on hardboard, gift to Auckland Art Gallery Toi O Tāmaki by the artist, courtesy McCahon Research and Publication Trust

Jude Rae

I first came across the work of Colin McCahon in the early 1980s. “Victory over death 2”, the New Zealand Prime Minister Robert Muldoon’s famously backhanded “Gift to the Australian People”, was installed at the Power Institute, then located at Sydney University where I was an undergraduate art history student. It was a troubled time for me and I remember the painting very clearly. Large and stark against the blonde brick foyer in the Madsen building, it impressed me as crude and overblown: it felt like an affront to my early training in “classical” drawing and painting. It was incomprehensible and unnerving - and it was just what I needed…

Little did I realise that I would come to see this moment as the beginning of my art education proper, and that a decade later I would find myself in New Zealand following in the footsteps of this extraordinary painter. Not long after my encounter with “Victory over death 2” I dropped out of my post graduate art history studies, found a studio and started to paint in earnest. In retrospect it seems both ridiculous and obscurely admirable that at this point I gave my young self ten years to have a solo show. Of course the visual arts was not the “industry” it has since become, so this did not seem quite as pessimistic as it might now. That said, I think it does reveal my wariness of an art world that felt alien and frightening, but nevertheless must be actively engaged. Looking back I can see that one of the aspects of McCahon’s work - it’s declamatory nature - had already left a mark on me.

I arrived in New Zealand via London in early 1990 considerably more familiar with contemporary art discourse and certainly more aware of the work of Colin McCahon. By that time the presence of this surprising New Zealander had been felt in Australia, his paintings having made a strong impression during the 1984 Sydney Biennale. It was not long before I began to get a sense that this increased recognition, perhaps fuelled by the artist’s recent death, was felt by some as overwhelming, even oppressive. In an environment where notions of originality and provincialism had yet to be fully overtaken by the effects of art world globalisation, it seemed that Colin McCahon cast a long shadow in the country and culture he loved.

In Christchurch I met Julia Morison just prior to her departure for France and the Möet & Chandon residency, and through her friends and colleagues became involved in the initiation of South Island Art Projects (later to become The Physics Room). SIAP gained QEII Arts Council support to develop regional visual arts projects and as the inaugural Director I found myself driving from one end of the South Island to the other. I will never forget the jolts of recognition as I saw the country through the eyes of McCahon: his paintings were everywhere, from the foothills of north Canterbury to the primordial light of the West Coast and Otago.

My decade in New Zealand was quite literally the making of me as a painter. The refinement and lyricism of New Zealand Modernism gave me a new understanding of the importance of formal structure in painting and allowed me to make a reassessment of my “realist” roots. The influence of McCahon was at once more powerful and elusive, involving aspects of painting that are notoriously difficult to describe: the sense that a painting could manifest something like integrity - a vision of wholeness arising from a fusing of the descriptive and tactile elements of painting into an overarching formal structure. From the painter who wrote “I will need words”… paintings that defied words.

By the time I left Auckland to return to Sydney it was the turn of the century. I had found the challenge that painting offered me and the will to pursue it. In 2004 the Stedelijk exhibition “A Question of Faith” finally arrived at the Art Gallery of NSW and included in it was that most lyrical (in both form and content) of McCahon paintings “The lark’s song”. Once again the work of Colin McCahon offered me a transformative experience. I remember standing in front of the painting, this time embracing incomprehension and sensing obscurely that painting had indeed become, for me, a question of faith: the way I would make sense of the world and of my life.

Painters explore the space between object and illusion, creating and exploiting the ambiguities that hang suspended between depiction and materiality. McCahon reminds me that this is the simple and enduringly subtle fascination of painting: that a rough division of coloured mud on loose canvas is just that, and it is the Canterbury horizon; that the dense and fluctuating white trace of a Maori poem on two wooden doors painted black is - in all its fragility - just that, and it is a mackerel sky, the glint of light on the Manukau with drifting clouds……