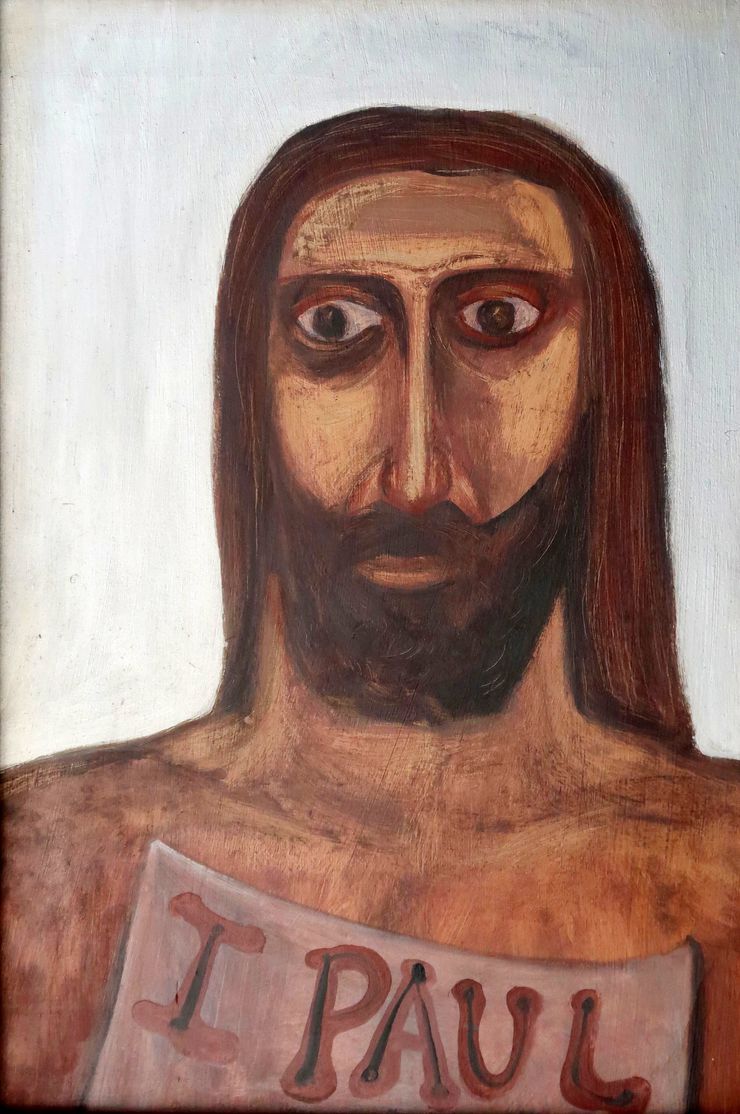

I Paul

I, Paul, 1948, metallic paint and oil on cardboard, 621 x 418 mm. Private collection, courtesy, McCahon Research and Publication Trust

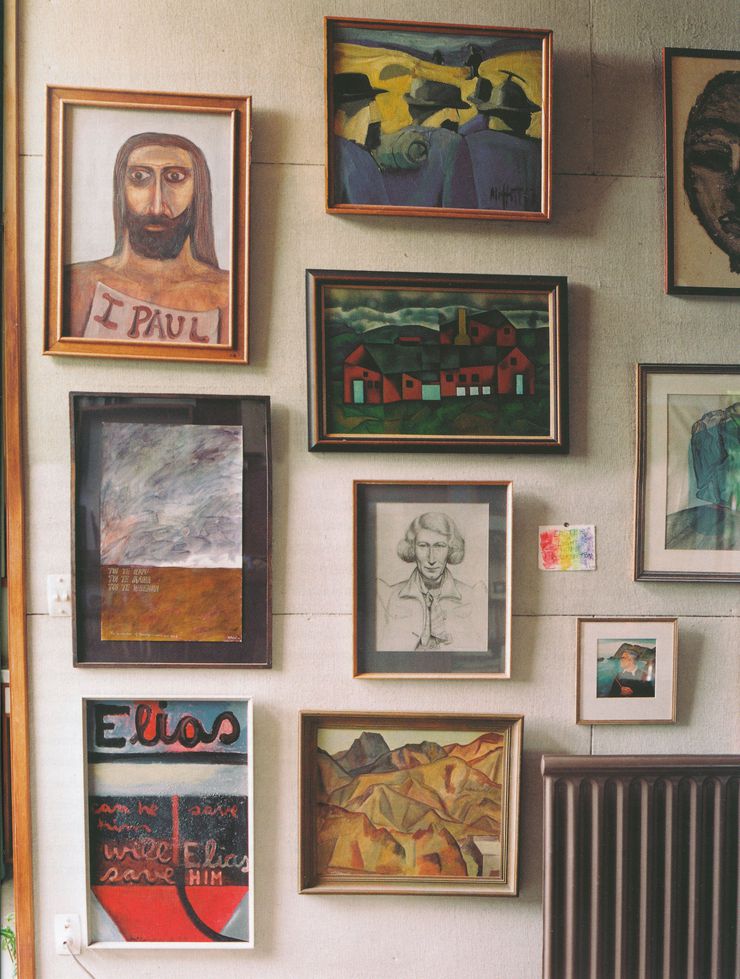

Grant Banbury, Photograph of Doris Lusk's Lounge Wall, 1990

Grant Banbury

A bicycle ride I three McCahons I and a dry sherry

The cycle ride didn’t take long. One street over from my Worcester Street flat, along Gloucester St past the CSA Gallery where I worked, and a few blocks further east, I arrived. This was the heart of Linwood, Christchurch. It was just before 7 pm. At the end of the shingle driveway, I put my bike just inside the carport and entered the house clutching sketchbook and drawing material. Five or so people were gathered inside for a life drawing session. The only male, I was the youngest by decades. We proceeded through the lounge and entered the studio where the furniture, old and worn, felt homely, lived in. A settee with rug and red cushions, assorted fabric chairs with wooden arms, an antique-looking burner – fed with coal and coke that kept us toasty on chilly winter nights – an easel and paint trolley. Jacqueline Fahey’s luscious oil, Last Summer hung on the wall. Green curtains sectioned-off half the studio, behind which loomed an electric kiln, wall-mounted Zip, a tall dresser, sink and a practical worktable. This was the ‘80s and I was a recent fine arts graduate in my 20s … I was a little nervous as this was the home of the famous artist Doris Lusk ...

Doris taught me at art school in the late 70s and, over the intervening years, we had become close friends. She influenced the direction of my life in numerous ways, although at this point I had no idea I would in 1996 (six years after her death aged 73), co-curate a major survey of her work for the Robert McDougall Art Gallery.

I remember on occasions as the drawing session got settled and the model posed, Doris would exit briefly to fiddle with a crackling radio in the lounge – it was always National radio, always classical music. Mostly we worked with pencil or conté but occasionally observed Doris splashing watercolour about with characteristic fluency and speed. At the end of each session a dry Fino sherry was served, and we talked. For a brief few years the group met regularly. With a conviction that life drawing sharpened visual perception, Doris and Bill Sutton made sure it remained part of the curriculum at the University of Canterbury School of Fine Arts during their time there.

Doris' home, designed by architect John Trengrove in 1972, was an addition to an existing stand-alone studio and embraced several modernist features; floor to ceiling windows, built-in bookshelves and a dramatic steep pitched roof. The roofline created a high uninterrupted wall that ran the length of the lounge, with high square windows at both ends. Hessian-clad walls were fashionable during the 70s, adding texture. Here installed on the expansive wall, it was painted pale-grey to create the perfect neutral backdrop.

For anyone lucky enough to visit Doris' home, it was the massed salon-hang of New Zealand artworks that captivated, an art history lesson all in one. The sight was magical. Not one but three oil paintings by life-long friend Colin McCahon hung at the kitchen end of the wall. In part the installation paralleled Doris' creative life, acknowledging key friendships dating back to her study in Dunedin in the late 30s and gatherings in Nelson in the early 40s, her connection with members of the Group, teaching colleagues and former students.

Small personal touches were also evident on the wall: family snaps, images of grandchildren, a colourful card from her artist friend Ria Bancroft, a classic Rita Angus oil of Hawkes Bay (1965) and Leo Bensemann’s famous 1937 conté drawing of Rita, a Hotere work with Maori text, a Fomison monoprint from the early 60s and an intimately-scaled seascape by Quentin Macfarlane (1977). Further along (out of view in the image accompanying this article) hung an uncharacteristic Olivia Spencer Bower, depicting two images of Olivia’s mother in a sea of palette-knife blue oil paint, and a dramatic profile of Philip Clairmont’s wife Vicki (c1970). A couple of Doris' famous earthenware ceramic masks and, just beyond the end of the wall, three abstract reliefs by Don Peebles looked as if the wooden door they hung on was part of the works themselves.

McCahon’s remarkable I Paul (1948) was hung high as if surveying proceedings … the protruding eyes elevated high in an elongated face. When first exhibited in Auckland in 1949 a critic referred to the painting’s ‘glaring aluminium background’1 and last year McCahon scholar Peter Simpson identified ‘a black-bearded figure with his name plastered on a label on his naked chest like a badge of identity’.2 And, in a tribute following McCahon’s death in May 1987, Doris linked the image directly to the artist:

I always used to imagine that in Colin McCahon’s striking early painting ‘I PAUL’ … which I am fortunate enough to own, there was a quite haunting self portrait; a prophesy of the future, indeed the portrait of a prophet. And towards the end of his life, when illness slowly changed him physically and mentally this resemblance to his own creation, to my mind was revealed much more tangibly – Colin always had a particularly direct and arresting gaze, and this confronts one with forceful exaggeration in the eyes of ‘I PAUL’…3

Doris once showed me a photo she’d taken of McCahon in the late 80s when his health had deteriorated. It was a back view of him walking towards trees … admitting, at this point, she couldn’t photograph her friend from the front.

Exchanging artworks between artists is common practice. Following time spent painting together in the Nelson region over the summer of 1942/43 Doris and Colin swapped works. Later, in 1966, McCahon gave Doris' Tobacco Fields, Pangatotara, Nelson (1943) to Auckland City Art Gallery. Much reproduced this image came to represent ‘Doris Lusk’ for too long. McCahon’s Landscape Pangatotara, The Crusader No. 1, (1942) hung in Doris' home until the time of her death. Both oils, and each showing the influence of Cézanne - Doris' populated with horses and people amongst the landscape vista in contrast to McCahon’s where he flattened the image by removing any sense of traditional perspective, a tobacco kiln peeking out from the corner of the frame.

The third McCahon gracing the wall was Elias (1959), one of a large series of ‘written paintings’ which explored the theme of the Crucifixion and concepts of doubt. Following McCahon’s impressive 1959 solo exhibition of new paintings at Gallery 91 in Christchurch, he gifted the work to Doris. As McCahon couldn’t attend the opening Doris spoke … later, in a letter to McCahon, she enquired: ‘Since you have offered me a painting may I have one of the warm “little” Elias ones. Apart from some of the very large compositions I like those the best.’4

It’s no surprise when noted photographer Marti Friedlander visited Doris in the late 70s to record her for the handsome publication New Zealand Painters A-M (1980) she documented the artist with her collection. Friedlander’s black-and-white image shows Doris in a moment of contemplation (collection Auckland Art Gallery). She appears in the lower right-hand corner of the composition looking down. It’s an image that clearly emphasises her treasured collection – all three artworks in the picture (Angus and two McCahon paintings) are cropped … it’s an image that speaks not only about Doris but also of her environment. The raking light cleverly highlights the painting’s textural surface, so favoured by McCahon at the time.

It always intrigued me that Doris lived in the same street as the CSA Gallery, a venue and an organisation that played such an important role during the 50-plus years she lived in Christchurch, both as an exhibitor and, at times, in a governance role. And, of course, from 1968 to 1977 it was the site for the famed Group Shows for which Doris, Colin McCahon and other notable artists were key players.

[1] Unidentified author, New Zealand Herald, 16 August 1949, quoted in Peter Simpson, Colin McCahon: There is only One Direction, Vol. 1 1919-1959, AUP, 2019, p. 134.

[2] Simpson, Op. cit., p. 129.

[3] ‘Doris Lusk remembers Colin McCahon’, Bulletin: The Robert Art Gallery, No. 52, July/August 1987, unpaginated.

[4]Doris Lusk letter to Colin McCahon, 2 [November 1959], E. H. McCormack Research Library, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, quoted in Simpson, Op. cit., p. 268.