The Fourteen Stations of the Cross

The Fourteen Stations of the Cross, 1966, synthetic polymer paint on 14 sheets of paper, 750 x 555 mm. Collection of Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, courtesy McCahon Research and Publication Trust

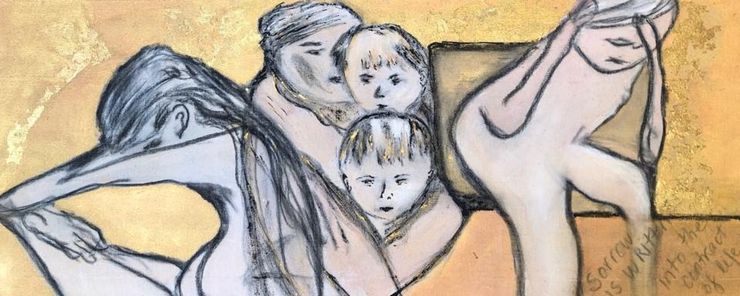

Donna McDonald, Grief Observed, 2019, mixed media on canvas mounted on board, revisiting paintings by Van Gogh, Kathe Kolvitz and Bea Maddock

Donna McDonald

Contemplating art as an autobiographical response

Whether we make, look at, or talk about paintings, the nature of our engagement and the tenor of our responses will most likely spring from a personal story. We know that our lives do not roll forwards as a single narrative arc; and that we create order out of confusion in hindsight. For some of us, art helps us to create that order, to make sense of our past, or at the very least to find consolation. We do not necessarily acknowledge this as a spiritual engagement. Indeed, the role of spirituality and overtly religious paintings in the visual arts canon is something that ‘many art historians have been slow to recognize and/or hesitant to acknowledge’(Schaefer 2018, np).

Colin McCahon’s body of work resonates with me for many reasons, but none more so than his series, The Fourteen Stations of the Cross (1966). To understand why, we need to go back to June 1987, when my infant son, Jack, died suddenly in his woven cane cot in the early hours of a winter morning in Melbourne. In the first few years following his death, his absence was a physical weight: my arms ached to hold him, my voice strained to call out his name. In time, his absence gave way to a spiritual weight, a never-ending existential question. ‘What am I to do?’ I examined this question relentlessly and actively: I engaged with my days with intensity and vehemence. I wrote about my love and sorrow for Jack. I worked hard; I achieved much. And yet … but still … that existential question remained unanswered. In recent years, I was given to understand that it was unbecoming of me to still be alluding to the absence of my son. After all, so much time had passed, hadn’t it? I needed to hurry up with my grief! The early urgency to get through the milestones of grief and loss is long gone. My heartache has solidified, as if it has been preserved in amber. The years continue to unfold, collapse, give way to new years. Jack’s absence continues to be ever-present in my life.

And then, in September 2018, Colin McCahon entered my life and pierced what de Botton and John Armstrong might describe as my ‘psychological frailties’. Or rather, I entered the Auckland Art Gallery where I saw McCahon’s Stations of the Cross, a series of fourteen images arranged in numbered order along a path, the Way of Sorrows, and fell into a reverie of contemplation.

Contemplating McCahon: the quick, the slow and the enduring

I tried to ‘do’ McCahon’s paintings quickly. I was in Auckland as a tourist for just a few days with a hectic itinerary of places to go, people to see, meals to share. I was in such a restless state of mind that my first response to McCahon’s series was to quibble about the number of stations. As a recovering Catholic, I thought there were only twelve stations. I even whipped out my phone to Google-search ‘How many Stations of the Cross are there?’ Having satisfied myself that neither McCahon nor the Auckland Art Gallery had embarrassed themselves for 38 years by being biblically innumerate, I nevertheless still attempted to ‘do’ these paintings quickly. I strode down that Way of Sorrows in a quick march, because I had already seen that the gallery held another series of McCahon’s paintings, recording the sensuousness of the Otago region. I wanted to hasten across the gallery floor to those works.

But McCahon’s Fourteen Stations held me close. I went back to the beginning, to the first Station. Stood still. Willed myself to stand still, even while giving the side-eye to the second and third Stations, before reorienting myself to the first one again. McCahon numbered each painting in the series and inscribed each with its traditional caption:

I. Jesus is Condemned to Death. II. The Cross is Laid Upon Him. III. He Falls the First Time. IV. Jesus Meets His Blessed Mother. V. Simon is Made to Bear the Cross. VI. Veronica Wipes His Face. VII. Jesus Falls the Second Time. VIII. He Meets the Women of Jerusalem. IX. He Falls the Third Time. X. He is Stripped of His Clothes. XI. He is Nailed to the Cross. XII. Jesus Dies on the Cross. XIII. His Body is Taken Down. XIV. He is Laid in the Tomb (See: Bloem and Browne 2002, 206-207).

As I retraced my walk more slowly along the Way of Sorrows, I felt the pull of each painting more deeply, while puzzling my way through a yearning which had arisen within me.

Despite my long-ago convent school art education, I had not heard of McCahon nor been exposed to his paintings, despite their wellsprings of spirituality. I did not know his personal story nor his aims as an artist. I was the naïve observer. Standing before his paintings that day, I could describe their simple iconography of broad flat expanses of colour in nuanced tones of grey, black, and sand; shifting horizons; and angled light-filled lines—just one or two, never more—cutting their way across the surface. (See Bloem and Browne 2002, 98-99, for a more detailed description). Nevertheless, I could not discern McCahon’s intentions in the ascetic way he rendered this solemn Christian narrative, traditionally painted in almost lurid detail depicting Jesus Christ’s torment and the lamentations of his followers. Nor could I draw any inferences from his images or confidently assign meaning to those images based on what I thought I already knew about Jesus Christ’s bearing of the Cross to Calvary. (See Lenette 2016 for a discussion about a simple four-step process for the naïve observer when considering images).

And yet, McCahon’s extreme parsing of the Passion of Christ to just a few elements resonated with me deeply. I had entered the Auckland Art Gallery as a tourist in a hurry, keen to undertake a secular experience of looking at attractive paintings before moving on to my next tourist experience. Instead, I encountered something much deeper: I felt shaken by this radical updating of my girlhood spiritual practice of walking to a Station, standing still before it, contemplating it, and then travelling on to the next Station. Fourteen times.

At the fourteenth station, I turned my head over my left shoulder and took in all of McCahon’s Stations in one sweep. I walked towards the centre of the room, looked at them all again as if they were a single work, and felt a stillness settle over me. My restlessness had given way to a quietude.

I went home. My experience of McCahon’s Fourteen Stations of the Cross went with me and has since infused my life in unexpected ways.

Responding to Colin McCahon: ‘A Grief Observed’

On my return home, I embarked upon a flurry of research. I learned more about this unsettling artist whose works had nevertheless established a settling within me, even if only temporarily. McCahon’s series, The Fourteen Stations of The Cross can, of course, be read in many ways, beyond memorializing the crucifixion of Christ. In their extraordinary simplicity, I have come to comprehend it and indeed, to embody it as a gateway to understanding personal sorrow with greater insight, dignity and hope, by contemplatively witnessing the love and grief of others. Like Cushla Dillon (2019), I sensed that I had found in McCahon ‘a co-conspirator, privy to the shadow self, sending messages from the spiritual darkness below to the land of satiation and excess above’ (np).

In its totality, The Fourteen Stations of the Cross conveys ‘a sense both of time and timelessness’ (Brown 1993, cited in Bloem and Browne 2002, 206). The progression from one Station to the next occupies real time, while the sense of timelessness is conveyed by the slow and solemn rhythm of the series, ‘whose depth cannot be fully understood without contemplative solitude’ (Brown 1993, cited in Bloem and Browne 2002, 206).

My need to walk past these paintings, mirroring the walk along the Way of Sorrows, was consistent with McCahon’s decision ‘to paint images “to walk past”’ (Bloem and Browne 2002, 180). As Bloem and Browne (2002) observed:

By introducing this requirement, McCahon succeeded in conveying within his paintings a continuum across both time and space … or the journey from the temporal world to that of the world beyond (180-181).

The viewer who undertakes this walk and takes the time to gaze upon McCahon’s largely monochromatic rendering of the Way of Sorrows—unpeopled and inscribed with just a few marks—is invited to overlay the New Zealand landscape with her own visual memories and impressions of loss, grief, and love, so drawing consolation from experiences which are witnessed and shared.

These reflections settled so deeply within me that I was moved to tackle de Botton and Armstrong’s (2013) call to artists to portray contemporary images of sorrow, and embarked upon my own arts-based exploration. Having already written over the years about my maternal grief (McDonald 1991, 1997, 2013), I researched historical and contemporary images of maternal sorrow and bereavement and chose to revisit the art works of four artists: Vincent Van Gogh, Kathe Kolvitz, Bea Maddock, and an unnamed photographer. I then made a prototype for an artist’s book, illustrating excerpts from my memoir of love, grief and loss ‘Jack’s Story’. Finally, I painted two larger works in mixed media on canvas, A Grief Observed’ and Grief Dares Us to Love Again.

The contemplative power of witnessing art in slow time

My 2018 encounter with Colin McCahon’s paintings in the Auckland Art Gallery—which astutely establishes the necessary slow space in which the timelessness of his works can be experienced—was the catalyst for developing my own personal arts-based expression of sorrow. In turn, this led me, as an arts therapist, to develop a therapeutic creative arts framework to support people experiencing enduring sorrow. It comprises a triad of processes: writing narratives of personal grief; contemplating visual arts images of sorrow; and creating visual arts images of sorrow in response to those images and incorporating the personal grief texts. In this way, the grace of McCahon’s 20th century response to the crucifixion, transposed to New Zealand, illustrates the regenerative and contemplative power of art when it is witnessed in slow time.

[1] Bloem, Marja and Browne, Martin. 2002. Colin McCahon: A Question of Faith. Craig Potton Publishing: Nelson, New Zealand and Stedelijk Museum: Amsterdam.

[2] Brown, Gordon H. 1993. Colin McCahon: Artist. Auckland, NZ:Reed Books.

[3] Crow, Thomas. 2017. No Idols: The Missing Theology of Art. Sydney Power Publications

[4] De Botton, Alain and John Armstrong. 2013. Art as Therapy. London: Phaidon Press.

[5] Dillon, Cushla. 2019. ‘Entombment: After Titian’. McCahon House. https://mccahonhouse.org.nz/100/cushla-dillon/ Accessed November 2019.

[6] Lenette, Caroline. 2016. ‘Writing with Light: An Iconographic-Iconologic Approach to Refugee Photography’. Forum: Qualitative Social Research 19.2. Accessed February 9, 2016. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs160287.

[7] McDonald, Donna. 2013. ‘When Time Stops: The Courage for Joy’. Chapter in Stories of Complicated Grief: A Critical Anthology. Ed. Eric D Miller, National Association of Social Workers Press, USA.

[8] McDonald, Donna. 1997. ‘I am a Mother.’ MotherLove 2. 173-180. Ed. Debra Adelaide, Sydney: Random House Australia, 1997.

[9] Donna. 1991. Jack’s Story. North Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

[10] Schaefer, Sarah. April 2, 2018. Review of Thomas Crow No Idols: The Missing Theology of Art. CAA Reviews. CrossRef DOI: 10.3202/caa.reviews.2018.98