All mortals are like grass

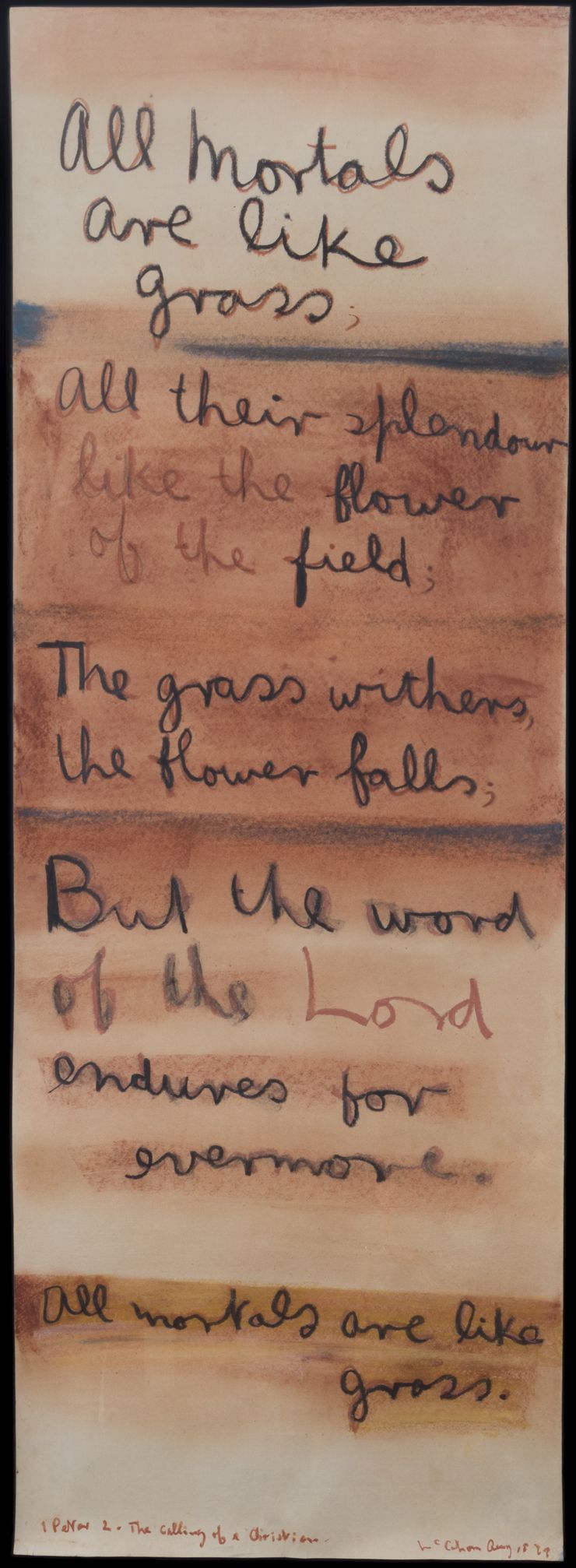

Colin McCahon, All mortals are like grass, 1969, conte and paper, 1551x558mm. Courtesy of Karl and Kay Stead, and McCahon Research and Publication Trust.

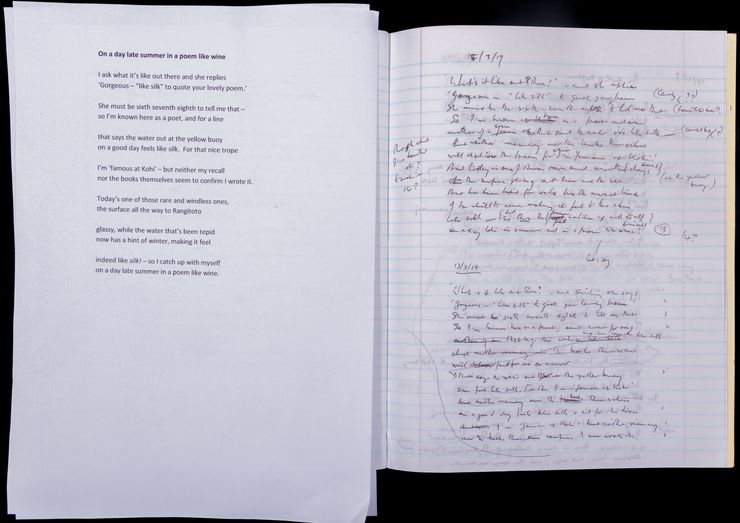

Working notebook of C.K. Stead poetry, 2019.

C.K. Stead

I choose this painting because I own it and am deeply attached to it. It was only the second McCahon Kay and I had bought. The first was one of his Helensville series, 1968, a green and black landscape painted in oil on board, in which his explanatory lettering on the back was almost as much a ‘McCahon’ as the painting on the front. The following year there was a new McCahon show at RKS Art, written paintings and drawings on paper, including the one I will describe. I have just browsed that series in the on-line McCahon catalogue and would make the same choice again. Colin was doing something in this series that made sense to him from the inside, but would only make sense to one who knew his work well already, and was able to recognize his particular vision and style. At a glance they are rough hewn representations of texts each of which has resonance and power, or in some cases just good sense; and it’s as though Colin is subjecting his art to the text, making it secondary to, and the servant of, the words. I did not like all of them, except insofar as I was already devoted to McCahon and felt the force of his personality in his script – as (in those days when we all wrote letters to one another by hand) I used to respond immediately to the script of Allen Curnow when it appeared on a letter. Some of the pieces in this series looked semi-inebriate, careless, a challenge, even an insult, to his admirers. There is something about McCahon’s work at this time that is so like James K. Baxter’s in his late sonnets – in ‘feel’, in spirit, in their determination not to be delicate or tasteful or ‘artistic’, not to look respectable or as if the work had been painted/written by someone wearing a tie and a clean shirt: the likeness is uncanny. The two, poet and painter, come from the South, from Dunedin, and the feel in both cases is of rebellion against Presbyterianism /Puritanism while at the same time acknowledging the power of God – as if both want to punish the God-fearing with the power they believe in; to smite them with it, like Old Testament Prophets. It is all quite alien to my temperament; part of my response is resistance and an inclination to mock; and yet I respond to them both wholeheartedly, not as message but as art. It’s a pity Colin didn’t do a transcription of one of Jim’s sonnets. He knew them well and responded warmly to a piece I wrote about them for Islands, with a note that ended in very McCahon lettering GOD IT WAS GOOD!

The text McCahon used in The calling of a Christian (1969) is a very beautiful one I knew already: ‘All mortals are like grass, all their splendour like the flower of the field; the grass withers, the flower falls, but the word of the Lord endures for evermore.’ The lettering is black, with now and then an edging of orange/red; but the one word, Lord, is red. These words are painted as if in the sky against a desert landscape of orange and yellow, with one streak of blue near the top that might have been, in the far distance, the river Jordon or the waters of Babylon where we sat down and wept – something distinctly Biblical. The words seem to hang forward, as if we are seeing them while looking down from an even greater height over this desert landscape, as God might have written them. The painting may be subservient to the words; yet it is also taking power from them.

During the past year I have been writing a second volume of autobiography. The first, South-West of Eden, covered childhood and youth up to the age of 23 when I first left New Zealand. The new one, South-East of Everywhere, goes from age 23 (1956) to age 53 (1986), when I left the university to be a full-time writer. But all through those thirty years I had been poet and fiction writer as well as literary critic, so a lot happened, and there was a lot to write about. Many important or significant New Zealand writers figure – Allen Curnow, Frank Sargeson, Janet Frame, Denis Glover, James K. Baxter, Keith Sinclair, Kendrick Smithyman, Hone Tuwhare, Alistair Campbell, Alan Roddick, Fleur Adcock, David Ballantyne, Ronald Hugh Morrieson, Bill Pearson, Marilyn Duckworth, the three Maurices (Duggan, Gee and Shadbolt), Lauris Edmond, Witi Ihimaera, Fiona Kidman, Ian Wedde – and the painters too, including McCahon – these and many more are the people who float in and out of the story of those middle-to-later years of our 20th century as I experienced it.

As for the thirty-plus years of my literary life that have happened since – my books will have to tell that story for me: at 86 (my present age) I must be realistic and acknowledge I won’t be around much longer. The Necessary Angel was my last novel, and The name on the door is not mine, my last collection of stories. While waiting to see South-East of Everywhere published I’m writing what will be called (probably) Last poems – coming back to poetry which I’ve always said was ‘first base’. (The example in draft form illustrated here is a sonnet (open form – i.e. not rhymed, and the 14 lines spread down the page in pairs) which Baxter borrowed from Lawrence Durrell and I borrowed from Baxter. C.K. Stead