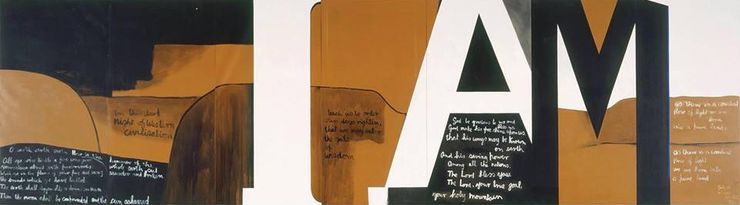

Gate III

Colin McCahon, Gate III, 1970, synthetic polymer paint 3050x10670 mm. Courtesy Victoria University of Wellington and McCahon Research and Publication Trust.

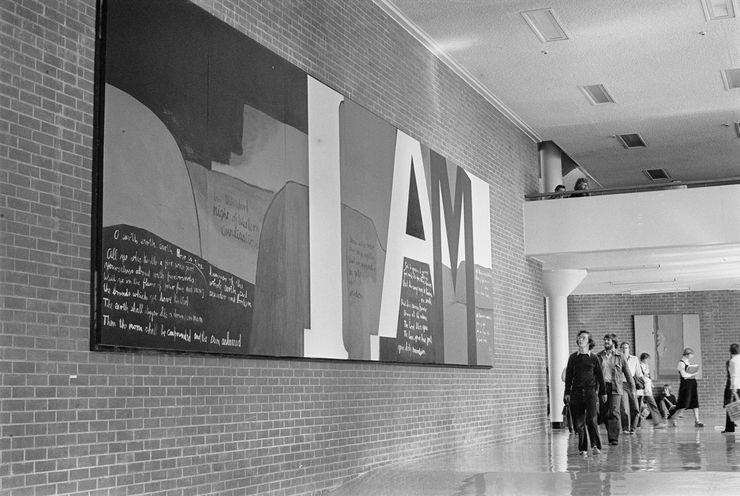

View of Colin McCahon’s Gate III on display at Victoria University of Wellington in the 1970s (photo: Dominion Post, Wellington).

Christina Barton

Colin McCahon’s monumental Gate III (1970) might not be my all-time favourite, but it looms larger—literally—than any other in my relationship with the artist. As director of the Adam Art Gallery Te Pātaka Toi at Victoria University of Wellington I am the painting’s caretaker. I feel the weight of responsibility for the most significant and—at over ten metres long and three metres high—the largest work in the University’s art collection. As I write, we are preparing to tour Gate III to Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery for its first public outing in Tāmaki Makaurau since it was painted for Ten Big Paintings, an exhibition at Auckland City Art Gallery in 1971.

In curatorial terms, we’ve come a long way. I’m not sure anyone today would organise a show on the basis of the size of its contents. Nor would they pick ten male artists.1 But, as I tell my art history students, the Ten Big Paintings exhibition is best remembered as a sign of New Zealand’s growing confidence in its own culture. It was a statement show that offered artists the opportunity to paint on a public scale in line with international precedents as the inaugural exhibition in that institution’s new Edmiston Wing.

By this stage, Colin McCahon had finished teaching at Elam School of Fine Arts and was readying himself to paint fulltime—another marker of the maturing of the contemporary art scene. He used the studios at the art school over the summer to paint the seven panels that make up the billboard-sized painting. He had already produced large, multi-part works; in fact, this breakthrough came more than a decade earlier, in 1958, after visiting the USA and encountering works like Jackson Pollock’s Autumn Rhythm, Picasso’s Guernica, and Allan Kaprow’s Kiosk, an assemblage of moveable painted panels McCahon thought were some of the ‘most beautiful’ he saw on that eye-opening trip. But Gate III was altogether bigger, even than Victory over death 2, the painting’s closest cousin now the treasured possession of the Australian National Gallery in Canberra. This was completed in February 1970 on a single run of unstretched canvas, not quite six meters long. His ‘third’ Gate was so big, in fact, that McCahon could not see it in its entirety until it was installed in the Gallery, a risky move that gave the artist serious jitters that he might go ‘over the edge’ and produce ‘the biggest flop’.

Well, it wasn’t; or not for Tim Beaglehole, the history professor who for over thirty years almost single-handedly built Victoria University’s art collection. He was simply bowled over. After seeing the painting when the exhibition toured to the Academy of Fine Arts in the old Museum building at Buckle Street in Wellington, he immediately set about to raise the funds to buy the work for the University, convincing his colleagues on campus that they should acquire it, and securing a grant of half the asking price from the Arts Council that went to McCahon as an ‘award’ for his achievement (after dealer Peter McLeavey received his cut). It doesn’t sound much now, but that princely sum of $4000 was then the largest amount ever paid for a painting by a living New Zealand artist.

I can only applaud this courageous decision. I see this now as not just a bold acclamation of support for the artist or art in general, but as proof of a deeper belief that art can make a meaningful statement and offer solace in difficult times. McCahon’s painting is writ so large because he wanted to reach his public. He had a message for his audience that was at once grim and hopeful. Painted in the throes of the Cold War and facing the threat of nuclear annihilation, his words still ring true: “In this dark night of Western civilisation / teach us to order our days rightly, that we may enter the gate of wisdom.” How keenly his words must have resonated when the painting was hung on campus. And how apt they are still as we face similar and different perils.

For the thousands of students who have walked by Gate III daily, even the many who have probably never stopped to read McCahon’s handwritten script, it is the scale that speaks. The thing simply is too large to ignore. This is McCahon’s ploy to carry his message. We are taken on a journey, from the blackness that threatens to smother the massed hills at one end of the giant canvas, past the huge ‘I AM’—that thunderous declaration of existence—to the brightening sky above the ‘pure land’ to which McCahon delivers us. Even if the enormous letters are now grounds for dissention, as we question McCahon’s assertion of self-hood and baulk at his invocation of a Christian God, bridling at the assumption that he can speak for all of us, the painting still galvanises; it simply won’t be silenced.

That’s why we are excited to put the painting on the road, to have audiences confront the work that has graced our walls for nearly half a century, to give them the chance to talk back to greatness.

'A Way Through’ Colin McCahon’s Gate III will be at Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery between 24 August and 20 October 2019. The exhibition will then be staged at Adam Art Gallery Te Pataka Toi from 2 November 2019 to 22 March 2020.

[1] The other artists in this exhibtion were Don Driver, Michael Eaton, Robert Ellis, Pat Hanly, Ralph Hotere, Milan Mrkusich, Don Peebles, Ross Ritchie, and Wong Sing Tai.