The view from the top of the cliff

Colin McCahon, The view from the top of the cliff, 1971, watercolour, 794 x 589mm. Courtesy Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

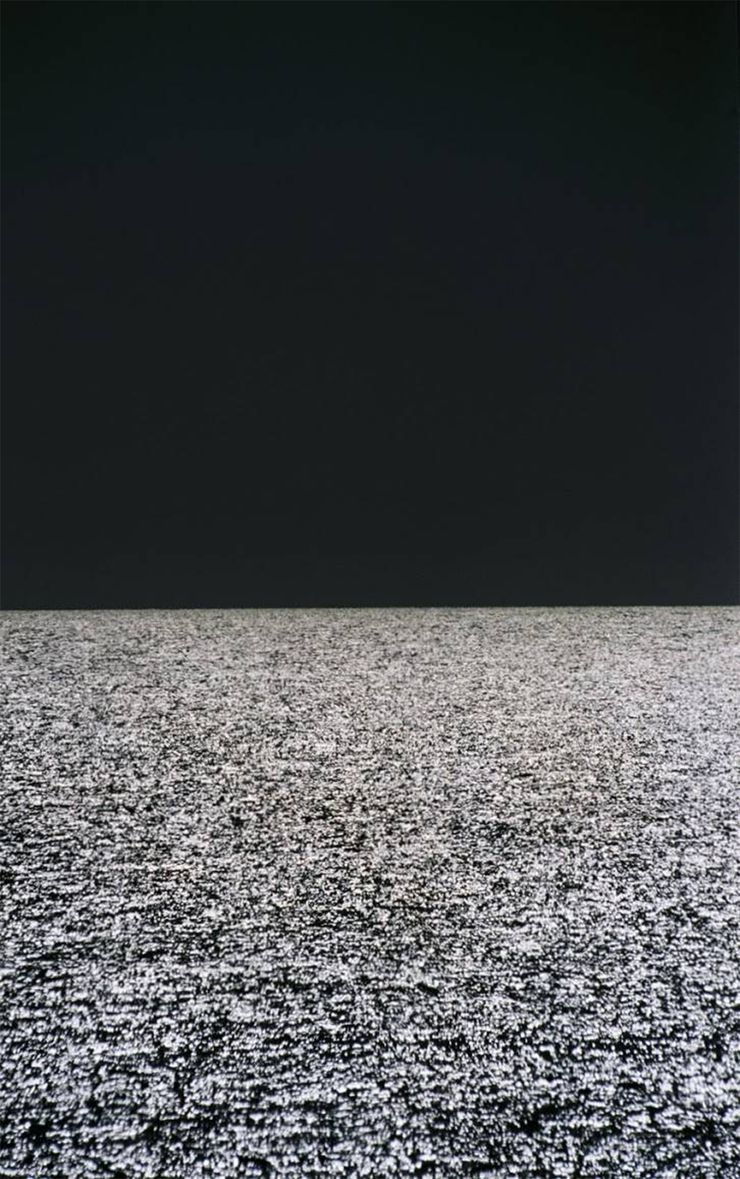

Brian Sweeney, Raumati Horizon, 2002, c-print, 720 x 480mm, Collection of Debbi Gibbs, New York

Brian Sweeney

Writing about Colin McCahon in the time of a global pandemic feels like a necessary act. Colin McCahon had the Depression, the War, and the Cold War to process during his lifetime, so he would have been imbued, as was everyone from these times, with end time scenarios. Whether the traumas of these eras found their way directly into McCahon’s devotional paintings of landscapes and scriptures is not clear to me, but every one of them is unmistakably a homage. It was a surprise to read that McCahon was ‘not religious.’ I imagined him as an escaped Roman Catholic. McCahon, it seems, was of no-fixed-abode except for his own self-created form of religiosity. I don’t believe you can be that close to scripture for decades and not be of it.

Emmerson and Thoreau, and the Fundamentalists of Massachusetts and Walden Pond, broke from the church to find God in nature. In his essay ‘Nature,’ Emerson writes:

I become a transparent eye-ball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God . . . I am the lover of uncontained and immortal beauty. In the wilderness, I find something more dear and connate than in streets or villages. In the tranquil landscape, and especially in the distant line of the horizon, man beholds somewhat as beautiful as his own nature.

In Auckland in late 2019 I visited Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki’s A Place to Paint: Colin McCahon in Auckland and Gow Langsford’s Across The Earth: 100 Years Of Colin McCahon. Staggering, figuratively, from these shows led me to genuflect; ‘Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners now, and at the hour of our death. Amen.’ The multiplicity of religious triggers—the altar, the cross, the angels, the journeys and ascensions, the beatification of land and sky and falls, the torrent of biblical texts—all spoke to me of a blazing spiritual drive in McCahon, of which reconciliation is a primary outcome.

In 2019 our company was among the instigators of Edmund Hillary’s centenary celebrations. In thinking about this event, I realised that Ed Hillary and Colin McCahon were born 12 days apart in 1919, conceived in the last months of World War One. Both then were born of relief, and of hope. Hillary came to represent the external face of New Zealand to the world for an era; McCahon brought to life our soul for us to see, deeply connected to whenua and spirit. Neither was a populist; Hillary had fame thrust upon him; McCahon received the ignorance of philistines. All stories mix past, present and future. Frances Hodgkins was 150 in 2019. Ernest Rutherford will be 150 in 2021. These are all lives we need to know about in order to kindle their inspiration and grit. In Auckland last October Sarah Hillary invited me to visit the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki conservation studios, and there on the workroom table was a set of Colin McCahon’s panels she was preparing for exhibition. It was a beautiful loop.

I’ve chosen the McCahon painting View from the top of the cliff (1971) because the title is a metaphor for things in life and endeavour. The view is from Muriwai looking west, part of a series of 10 watercolours exhibited by the great Peter McLeavey in 1972. McCahon was a superb colourist. He pushed the spectrum of emotional resonance to joy. He mined the horizon. A colleague who once lived in Malibu told me in response to my defining New Zealand as ‘the world’s edge’—a metaphor from Stephen Jay Gould’s theory of punctuated equilibrium from evolutionary biology, which proposes that change comes from the edge of the species where the population is most spare and new life forms have the greatest opportunity to emerge—that when Californians look at the Pacific they see a horizon line between sea and sky. When New Zealanders look at the Pacific horizon line from the opposite side of the ocean, they see wonder, possibility, and journey. This is what The view from the top of the cliff speaks of to me.

For 25 years our family lived weekends yearround at Raumati South at Kapiti (Raumati meaning summer), looking at the same westward vista as this McCahon painting. This oceanic horizon is the first in the world over which the sun sets every day. In its own way, a definition of infinity. This observation became an idiosyncratic phenomenon to document. As Colin McCahon’s The view from the top of the cliff is a dream, and as this horizon offers us solace as well as a risk-taker’s gambit, my accompanying picture of the view from Raumati South is, in 2020 terms, necessarily binary.

Between these two poles, 'Hail Mary, full of Grace, the Lord is With Thee.'

Readings

[1] Stuart McKenzie essay, Paradise Road by Brian Sweeney, 100 photographs, published by Charta, Milan, 2010

[2] Paul Stanley Ward essay, Colin McCahon: The Luminary, nzedge.com, 2009

[3] Zoe Alderton’s essay “Cliffs as Crosses: The Problematic Symbology of Colin McCahon,” Relegere: Studies in Religion and Reception 2, no. 1 (2012): 5-35

SweeneyVesty was founded by Jane Vesty and Brian Sweeney in 1987 and has its roots in the New Zealand performing arts of the 1980s. SweeneyVesty sponsored the 2004 documentary Colin McCahon: I AM directed by Paul Swadel, produced by Robin Scholes.

Purchase a print publication of McCahon 100 here.