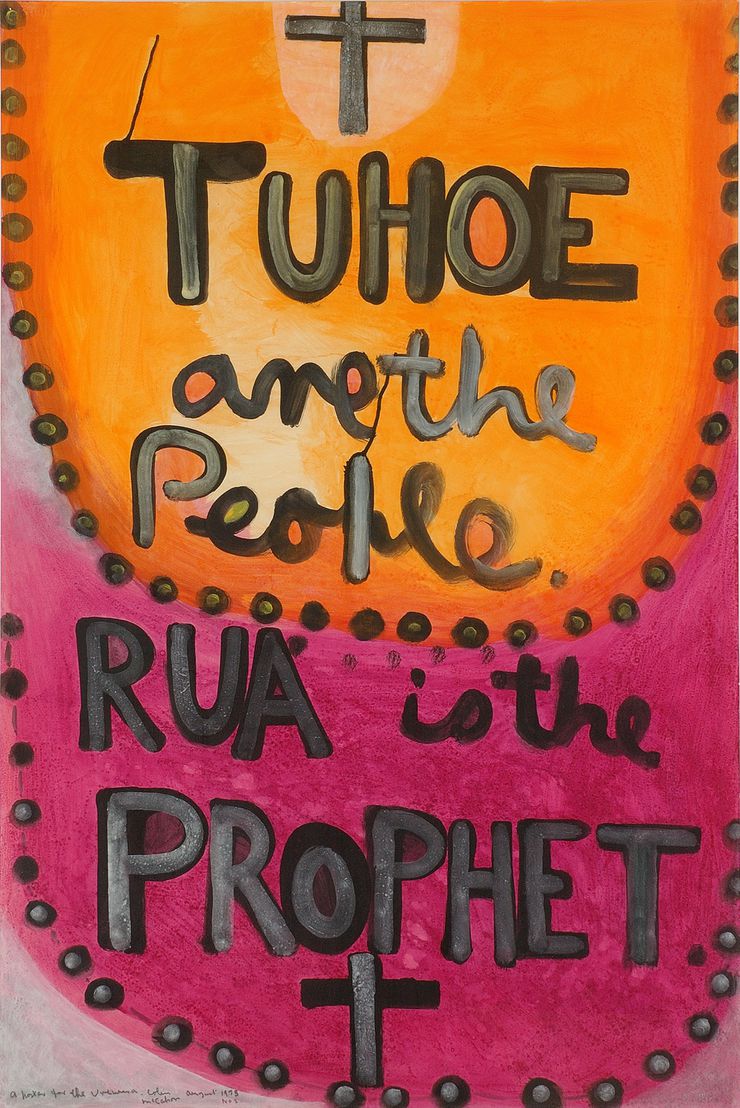

A poster for the Urewera no. 2

Colin McCahon, A poster for the Urewera no. 2, 1975, synthetic polymer paint on paper, 1089 x 720 mm. Courtesy Aratoi - Wairarapa Museum of Art and History and McCahon Research and Publication Trust

1966 American field scholar Bettina Prior in the korowai lent to her by John Rangihau

Ian Prior (left), John Stanhope and John Rangihau with Mokoia Island in the background, c. 1969

Bettina Bradbury and Kararaina Rangihau

Bettina Bradbury is a historian and professor emerita in the Department of History and Gender Studies at York University, Toronto. She recently returned to Wellington.

Kararaina Rangihau is a Tūhoe and Te Arawa tribeswoman, youngest daughter of John and Wena Rangihau

Bettina

‘Tūhoe are the People. Rua is the Prophet’, is what I always believed this poster work was called. The original painted poster hung for years in the kitchen of our parents’ house on Wade Street in Wellington; gracing breakfasts, lunches and dinners. Fit Wadestown commuters could enjoy its vibrant colours as they strode down or up the hill between home and work. Some have since told me that they marvelled at their glimpses of this bold orange and richly pink painting. Some worried that such a valuable piece of art was so readily visible to all. Neighbours, passers-by and visitors who knew our parents, Elespie and Ian Prior well, likely also knew that the house was seldom locked, and that when it was, the key was under the flower pot opposite the back door.

My sisters and I were privileged to grow up in a house the walls and spaces of which were increasingly occupied over the years by the sculptures, paintings and prints of mostly New Zealand contemporary artists. Works by Tanya Ashken, Barry Brickell, John Drawbridge, Ralph Hotere, Doris Lusk, Colin McCahon, Douglas MacDiarmid, Pat Hanly, Milan Mrkusich, Evelyn Page, Toss Woollaston—and others—moved at times from room to room, or left—for a while or forever—to hang on the walls of friends’ houses, or in the Otago School of Medicine at the Wellington hospital, where Ian worked.

Elespie had known some of the artists through her Dunedin based mother, Emily Forsyth and cousin, Charles Brasch. Around 1937 McCahon painted a dark cubist-like portrait of Elespie in ink and watercolour on wood. Evelyn Page painted a beautiful portrait of Elespie at Governor’s Bay in 1939. That same year, Lusk, McCahon, Elespie and Rodney Kennedy headed to Mapua for the summer, the artists among them inspired by Toss Woollaston to paint the Nelson landscape. Some of the artists were family friends and frequent guests, intermingling over the years with the eclectic mix of composers, musicians, conservationists and physicians, sociologists, anthropologists, poets and activists who enriched our growing up. Knowing the people who created some

of our art enriched our emotional attachment to it.

But McCahon’s A poster for the Urewera no. 2 (1975), which Ian purchased early in 1976, held different meaning for us. We sisters did not know Colin McCahon personally. This poster connected us to Tūhoe and the Urewera rather than to the artist. That link signified another privilege of our growing up. Ian could never have undertaken his epidemiological surveys in the Ureweras had John Te Rangiāniwaniwa Rangihau not coached and vouched for him. John opened doors and ensured that Ian and his team understood tikanga Māori. They became firm friends for life: two intelligent, caring men driven to improve the world in ways that mattered to them.

As children and teenagers this friendship meant that we spent time with John, Wena and their children in Ruatoki, Ruatahuna and Rotorua, hanging out, riding horses, and learning shards of te reo and tikanga. We pretended to sleep while John, Wena, John and Drury McCreary, Elespie and Ian talked and sometimes drank late into the night. I spent a school holiday with whānau in Whakatāne, another at the Rangihau home in Rotorua. My grasp of the deep-rootedness of racism in New Zealand was heightened after the latter trip when my headmistress suggested the bad cold I was nursing was probably a result of spending too much time hanging around in hot pools with Māori!

In 1966, when I was seventeen, I went to The United Sates as an American Field Scholar. John Rangihau and Keri Kaa made sure that when I spoke to American audiences about New Zealand it would never be only from a Pākehā perspective. John insisted that I take an incredibly striking korowai and bone patu with me to demonstrate the beauty of Māori art. I remain bowled over today by the fact that he entrusted a seventeen-year-old with such valuable taonga..

So, for me, as for my sisters, this joyously bright and colourful painting spoke of our link to the Rangihau family and through them to Tūhoe and Te Urewera. Now, as a historian, I see it as a powerful reminder of the brutality of colonialism; of events and processes whose legacies continue to scar lives and communities today. I think specifically of the atrocious attack on Rua Kēnana and the peaceful community of Maungapōhatu, acknowledged, finally, this September in the governmental apology and his pardoning. My father’s own view of the poster’s link to the colonial past was similar. In 1980 he wrote to Bronwyn Reid at the Aratoi gallery:

...a wonderful painting, great colour and an exciting statement about, Tūhoe, Te Urewera and how the Urewera National Park was annexed by the Crown without any opportunity for the Tūhoe to contest the decision. It is certainly a statement about the landscape of New Zealand and how the rights of the Māori were so often trampled on.

I have asked Kararaina Rangihau to consult her sisters about what this particular Urewera poster means to them; perhaps in relationship to the controversial one, or what it meant for it to sit in Ian and Elespie’s house in Wellington and then in the Aratoi Art Gallery in Masterton, Ian’s hometown to whom he gifted it. We emailed back and forth. Her responses came in words and poetry.

Kararaina

For our whānau first and foremost the painting is a symbol of the strong bond between us and the Priors. Both Ian’s and Dad’s love for one another was profound and deep. My older sisters have fond memories from their childhood of both Ian and John laughing and drinking; in deep conversations about everything—mainly Tūhoe. My sisters and I had a chat about your email, and they remember Elespie talking about McCahon and his art with them, and they couldn’t help laughing about the very different perceptions that Elespie and Ian each had of both people and art. You probably know Ian and Elespie gave the whānau three prints of that McCahon. Of all his work, it’s my most favourite because it’s

not as gloom and doom looking as the rest. I don’t know anything about art, but I do love that brilliant orange! It seems to take the heaviness out of Te Urewera colonial history.

This painting reminds us of two things. First, the infamous Te Urewera mural that was commissioned by the Department of Conservation for the John Scott building at Waikaremoana. It now hangs in the Te Uru Taumatua building at Tāneatua. Interestingly,

I recall our aunty in Waikaremoana talking about Dad going home to speak with the old people about it. The original name Colin painted was Tūtakangahau. The old people disagreed with that for their own reasons, so Dad had to tell Colin to remove it. Apparently, Colin painted over it, hence Rua Kēnana.

Secondly, the poster reminds us of Rua Kēnana’s prophecy of Dad when he was a child. This story was recounted to us by a respected Tamakaimoana elder living at Maungapōhatu. One of Dad’s closest cousins recounted the exact same story years later, and she believed that Dad was nurtured and raised accordingly by the old people in the hope that it would come true. As a child Dad was quite sickly, so his parents took him to Maungapōhatu for treatment and healing. There Rua saw the child and declared that should he live past the age of 21 years he would lead Tūhoe out of Te Urewera and ‘into the world’. Dad’s parents were devout Ringatū; his grandparents closely associated with Te Kooti and Tūhoe’s conflict with the Crown. So, any association with the ‘outside world’ was believed to be risky business on many levels.

I wrote this poem to express my thoughts about the poster...

My Father’s PrayerI cannot tell you about the rage in my heart

You will say be humble

I cannot breathe the same air as them

Soiled blood green with twisted roots

Colonial daggers hidden in shallow pockets

You will say be humble

The monocle of broken children

Once called leaders of tomorrow

Swept away by silver tongues and polished shoes

I hear the language but feel nothing

All I see are empty canyons

Hollow heads speak of Tūhoetanga

And still you say be humble

Mountains and mist sigh in vain

Valleys and rivers catch their tears

Pulled by the jagged winds of Tāwhiri

The sharp edge of neo tribalism

The pied piper

Another nail in our colonial coffin

The by-gone era has returned

How can you say be humble?

The long night still awaits

The slither of light you promised

Mothers and fathers beat the drum

Of white walls and chains, whiskey and rum

Grandmothers and fathers hang their heads

But no, be humble

Should I build bridges or burn them

Kidnap the silence through the noise

Or heed the carnage of yesteryear

Be humble?

Yearn for one another not the golden cow

Take no prisoners and bare the long brow

For you are the product of your people

And make no mistake the voice of a nation

I am humble so bury me deep

Giants amongst men, yearn for sleep

As dawn draws near, Mist Maiden rises

The good wolf wins

Sacred feet tread

Upon your prayer for women and land

Your mokos rise up and make a stand

Now you know My Father’s Prayer

Be humble Tūhoe, know your place

A moment between two eternities

Your past and future humbly awaits.

Finally, Bettina I just want to say, for me this McCahon speaks of the sacrifice Tūhoe made during a time in our history when poverty and disease were sweeping through rural New Zealand like the black plague. I think McCahon has captured the true history of this country: the Tūhoe resistance to colonial military power, the resilience to survive their scorched-earth strategy, and their strength to overcome the adversities of the 19th and 20th centuries. The painting speaks of hope, the will not to just live, but to aspire to a future our ancestors would be proud of.

Purchase a print publication of McCahon 100 here.