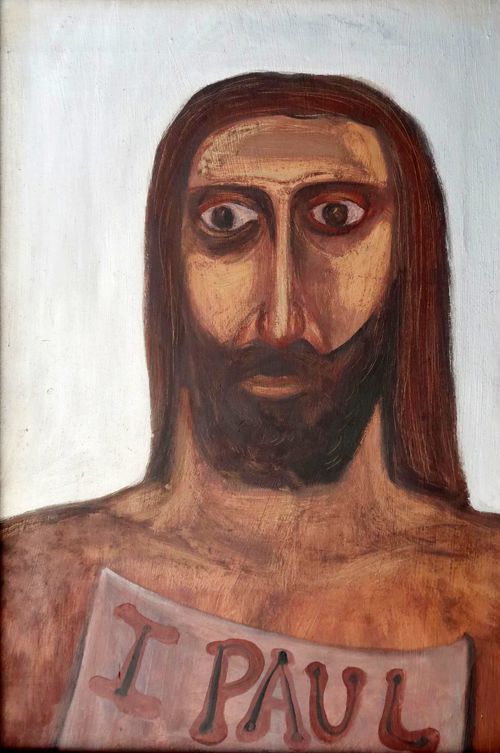

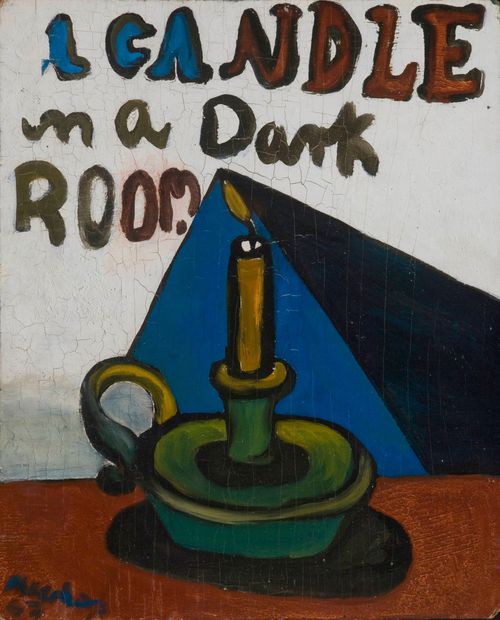

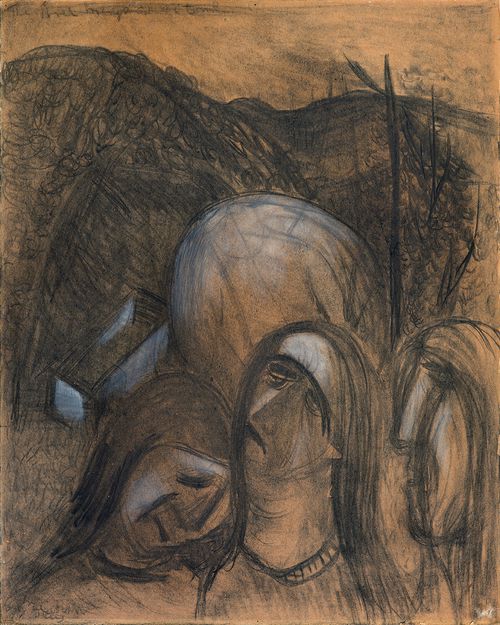

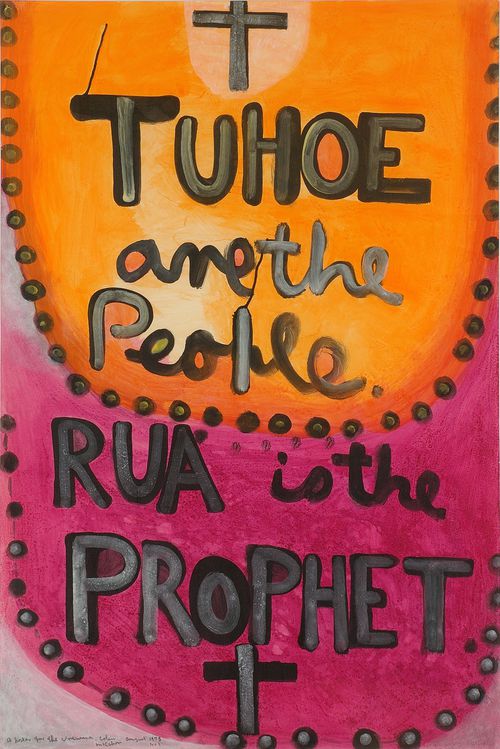

The Three Marys at the Tomb

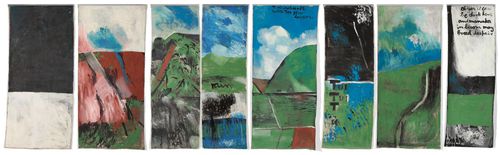

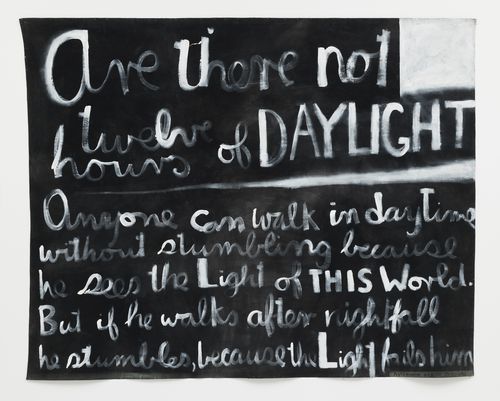

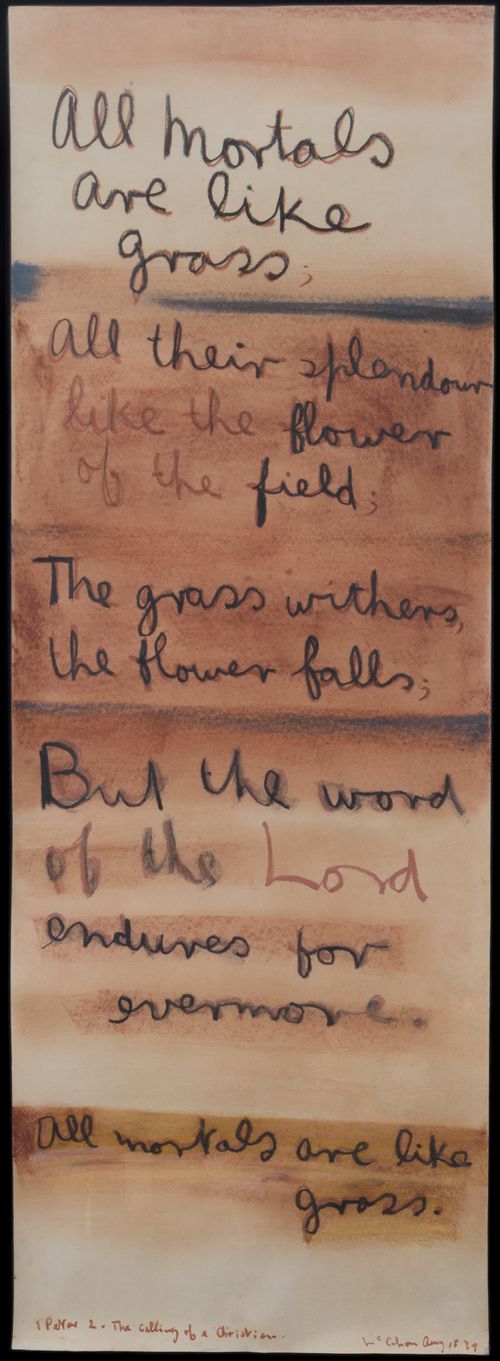

The Three Marys at the Tomb, 1947, on buff paper, 650 x 519 mm. Private collection, courtesy McCahon Research and Publication Trust

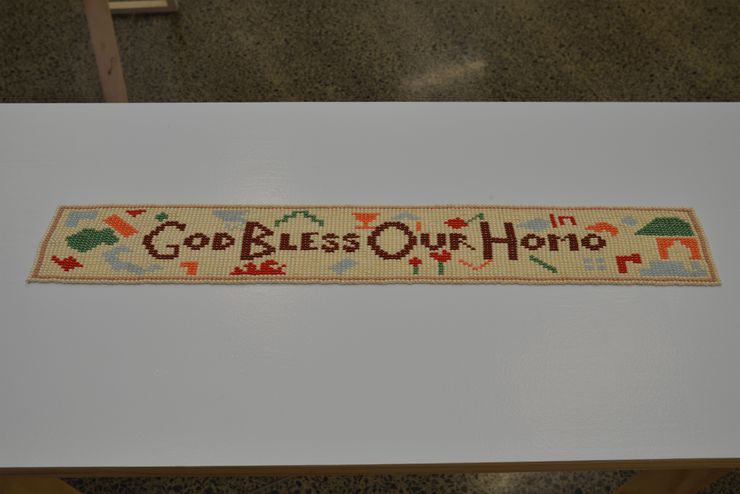

Areez Katki, Homecoming, 2019. Czech glass beads tapestry-threaded with mercerised cotton thread. Private Collection

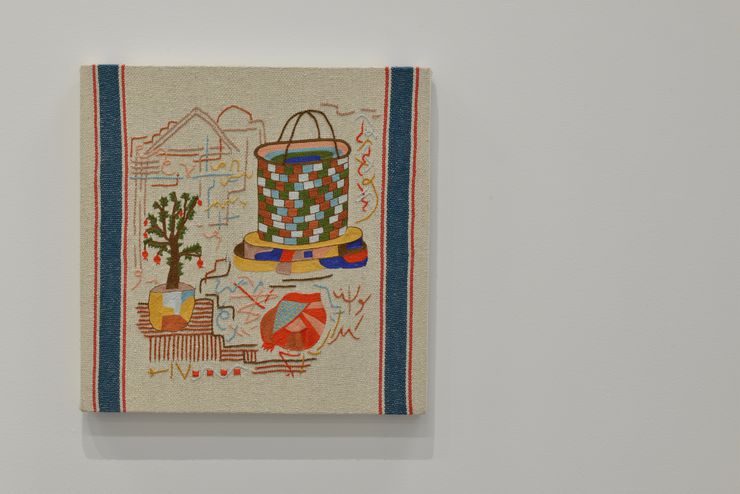

Areez Katki, It’ll Rot if You Don’t Chew Fast, Shirin!, 2018 Cotton thread hand embroidery on handloomed cotton Khatka. James Wallace Arts Trust

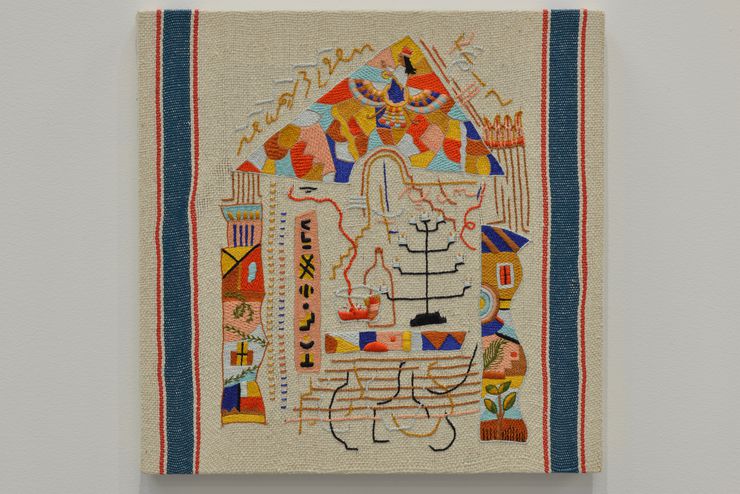

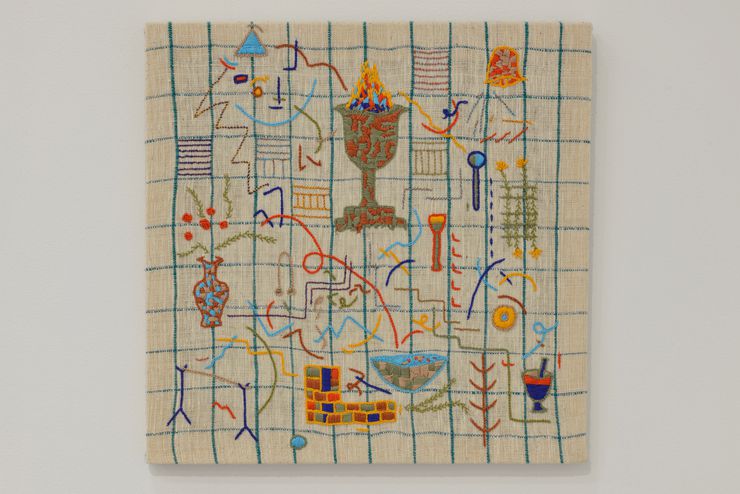

Areez Katki, Temple of Anāhita, 2018. Cotton thread hand embroidery on handloomed cotton Khatka. Private Collection.

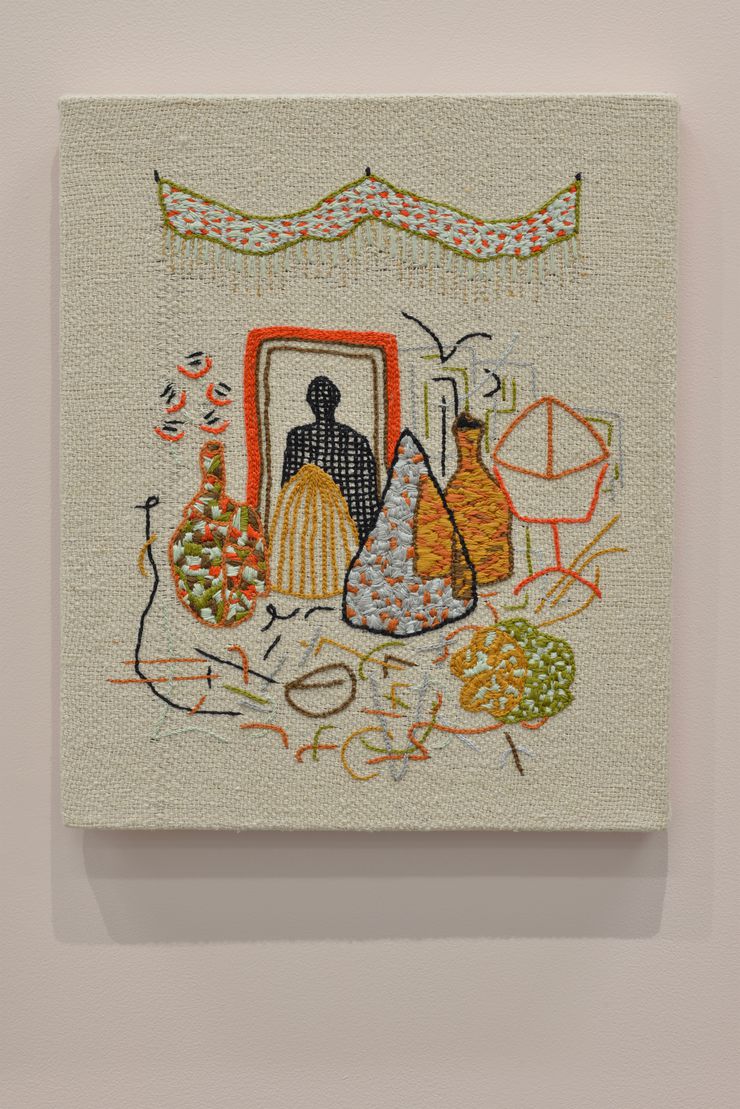

Areez Katki, Shrine (Still Life with Partially Squeezed Lime, 2018, cotton thread hand embroidery on handloomed cotton Khatka. Private Collection

Areez Katki, Nāvar Initiation (Zoroastrian Priesthood), 2018, cotton thread hand embroidery on handloomed cotton tea towel (green windowpane check). Private Collection

Areez Katki

One uncharacteristically warm summer afternoon in Dunedin, P and I had left our friend’s studio by the Harbour, readying ourselves to meet with Margery and Gary Blackman. I recall vividly the various refractions made between brightly hued sheds and brick laden warehouses, as we hurried toward Stuart Street from Dunedin’s waterfront.

. . .

We knew little about the great extents covered by our evening’s hosts; the night might’ve commenced like an unwieldly example of endurance, framed by a marriage bonded by two art practices––demonstrating both, the unity and depth in material knowledge that Margery and Gary Blackman had collectively procured over their years. We reached a point where Gary would collect P and I from Stuart Street and drive up to their home for tea. Margery and Gary graciously took us up the hill up several flights of stairs into their multi-terraced modernist home on Maori Hill. As we pored over exhibition catalogues and a collection of artworks that contextualised both of their prolific art practices, Gary took me aside and mentioned, rather gingerly, “––and there’s a McCahon in the mix too, you know. Bought it from a library sale when I was 17!”

I showed a cursory amount of interest in the matter, since we were running late for dinner. Gary was well aware that I’d already been through several tapestry fragments with Margery, only a few hours earlier, at the Otago Museum. And so at their home, Margery might’ve presumed that I’d be more partial to examining textiles woven by her and the women she learned her craft from—rather than an old McCahon drawing purchased in 1947. If this were the case, she was not incorrect.

. . .

Dinner was a lengthy affair at a small but vibrant restaurant that neither P or I can quite recall the name of––we were still tucked somewhere in Maori Hill, near the Blackmans’ residence. Margery took an hour to finish her Affogato and Gary continued telling us about their travels through Iran in the mid-1970’s; their remembrances of a pulsating art scene in Tehran, only a few years before the Islamic Revolution of 1979. I could sense P’s impatience by that point and held back from exhibiting my own. We were trapped in a booth, alcoved by two remarkable people who should’ve had more of our patience and attention. As we finally wrapped up and drove back to the Blackmans’ for a nightcap, P looked over at me in the backseat and whispered, “––at least now we might get to see the McCahon?”

. . .

Half an hour into a pot of peppermint tea and a few articles that we’d yet to look through, Gary shows a rather sleepy P through a catalogue of paintings collected by Charles Brasch. Moments later, he yanks a frame up from behind their Fredrik A. Kayser sofa and proclaims, “Ahh boys, here it is, my McCahon! Just a drawing that I felt compelled to purchase back in 1947,” wistfully dusting its frame as he continued, “This is when they held small exhibitions at the Carnegie Public Library on Murray Place.”

We discovered that Gary was, at the time, in his final year of High School and had an early interest in McCahon’s schematic developments; at a time when he was also becoming aware of some other changes that painters, particularly Colin McCahon, had instigated. An interest in factoring non-religious matters within religious tropes. The notion of New Zealand artists exploring Modernist expressions was thrilling for a seventeen-year-old Gary. Elegantly craning his neck toward Margery, “You remember, don’t you dear? Those early days when we never saw much outside of Christian or pastoral themes played out in fine art?”

“Well darling, we may have just gotten very lucky with the resources at hand––things were a lot easier for young artists in those days, especially those of us who were born Pākehā and attended art school.”

At this point I looked over at P and smiled: a nonagenarian who gets it, I suspected, was our simultaneous thought. It was left unwhispered from across the room.

. . .

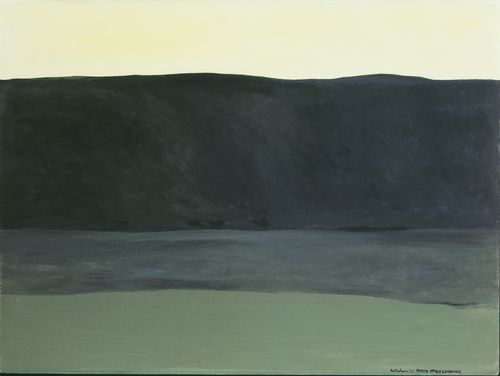

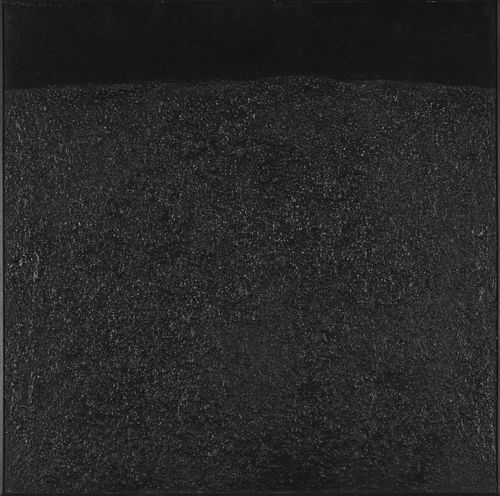

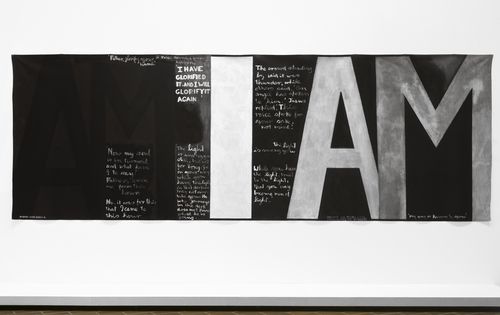

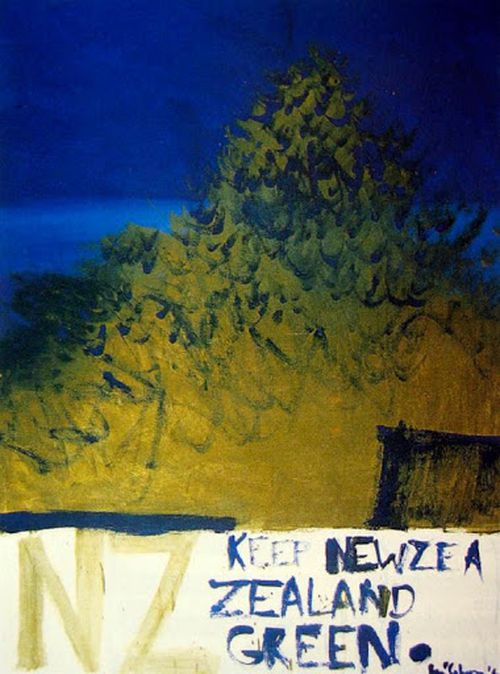

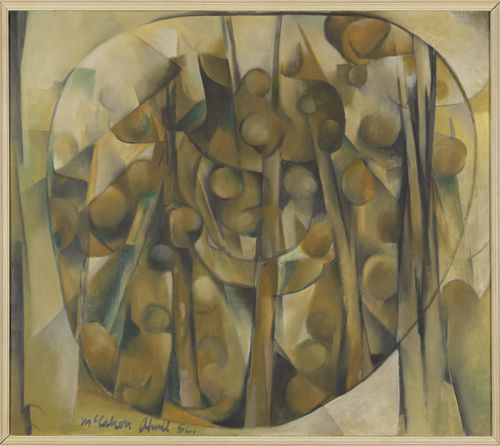

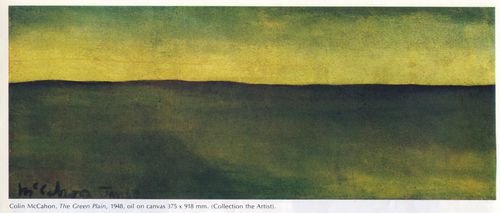

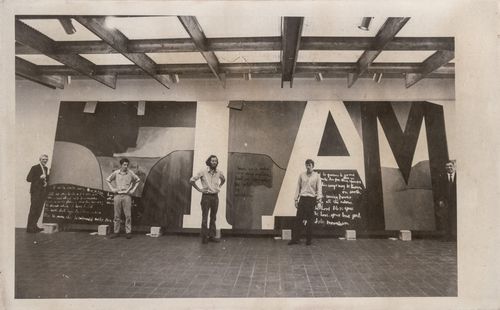

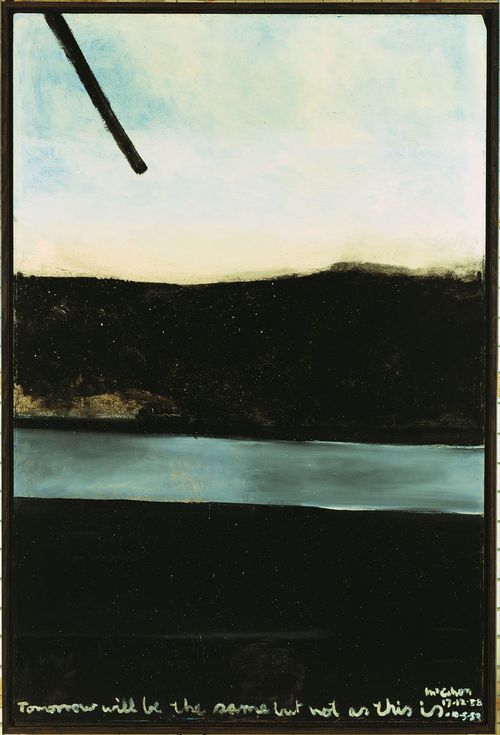

Three Marys at the Tomb [1947] is a small charcoal on board work that looks at matters beyond religion, indeed; the exploration of religious doubt is evident in works like these and several later paintings that emerged from McCahon’s oeuvre. This particular rendering of Three Marys, as Gary noted, did well to provide art historians with an indication of what had laid behind Colin McCahon’s interests, namely the psychology behind religious fervour. The facture of this panel, as I recall today, was something that P and I couldn’t quite come to grips with––how naïve and incongruent his figures must’ve appeared to us. Nearly afloat, before a backdrop that vaguely resembled the Nelson Hills; tweedy, almost self-referentially broken and wearied figures; the fated ills that womankind had, and would continually endure, under the brush of male painters. But this was not painted like McCahon’s more sophisticated pastoral renditions. Not like his grand-scale compositions or critiques around religion, Gary would remind us––Three Marys at the Tomb was a subtle study, executed sensitively with charcoal. It presents a schematic insincerity, perhaps intentionally, given that it was made at a time [post-World War II] when artists like McCahon harboured his generation’s intention to provoke their audiences. Both, the religious and conservative legacies of the post-war period, as well as his more dynamic modernist contemporaries in Aotearoa. The drawing took one thing from each camp and conflated those values to produce a newness that had only itself to lean against in a country as small as ours.

. . .

By midnight, P and I walked back up Stuart Street after bidding farewell to the Blackmans––worn from staying out late, far later than we’d expected. I remember sighing as we went past a shuttered-down Albar, where we spent most evenings In Dunedin. “I guess we’ll remember this one eh?” –– “Certainly, my darling. At least we learned a thing or two about McCahon and a pair of his contemporaries, huh—” followed by P’s limply proclaimed, “––I suppose Dunedin isn’t quite so dreary as we’d expected.”

. . .

As Margery and Gary exchanged impassioned comments about the way McCahon examined his pastoral and ethno-religious subject matters using modernist methodologies, I remember smiling, perhaps only inwardly, as P dozed off on a Danish armchair cushioned by Margery’s tapestry samplers. I entertained an idea around where we might be, should the occasion come, when one had to address the conceptual frameworks that drive so many contemporary artists in Aotearoa today. What works or artefacts from our time might endure—in such an embracing manner—should P and I live and continue to work beside one another, by the ages of 89 and 90.

Warm acknowledgments are to be extended to: Margery Blackman, Gary Blackman and Paul G. Johnston.