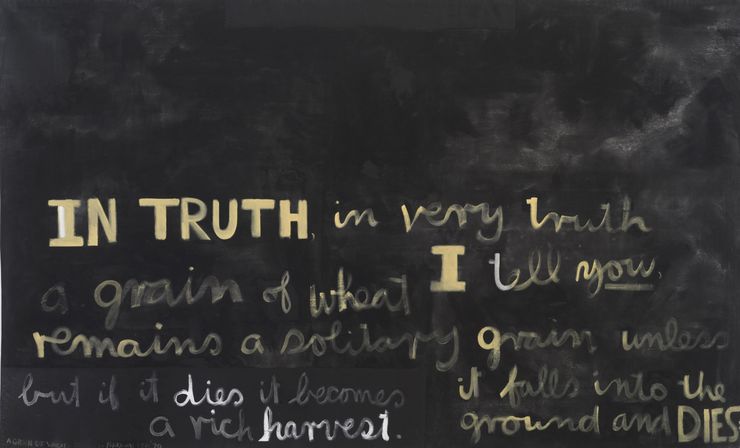

A Grain of wheat

Colin McCahon, A grain of wheat, 1970, synthetic polymer paint on unstretched canvas, 2080 x 3435 mm. Courtesy Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa and McCahon Research and Publication Trust.

Trying to be better - Coffee Supreme Auckland team, 2019

Al Keating

I was introduced to Colin McCahon by my art teacher at Waitākere College, Mr. Giles.

He thought I’d enjoy him because we had West Auckland, a religious upbringing and creativity in common.

He was right.

I loved McCahon’s use of black and light; his perfectly imperfect scrawled text—something like an ill-prepared sign writer’s apprentice—and his big bold works that spanned entire walls, shouting truths, and whispering confessions of doubt and weakness simultaneously.

I thought he painted landscapes like Hergé might have painted New Zealand, should Tintin have ever ventured this far. I could see Auckland’s West Coast in his works, even when it was not the subject of his paintings.

I grew up in deep West Auckland. ‘West Auckland’, back when it was the edge of the city. Our neighbours grew strawberries, grapes, and apples, often with a piece of massive earthmoving equipment decomposing somewhere on the section. Just beyond our neighbourhood was the mystical West Coast.

My parents found an old bungalow out in Cornwallis that had been relocated from Kohimaramara a ‘thousand years’ earlier. They bought it for five grand, then did the obvious thing with it; cut it into three, strapped it onto as many trucks and reassembled it up on Royal Road, Massey North. Dad spent the next 20 years working to get the Kauri floorboards to almost line up, finding and filling the elusive cracks that let the drafts in.

I remember a few tough periods. It might have been the draughtiest house on the street but my folks made it the warmest home in the west. Mum was inadvertently pioneering plant-based eating, when it was something one might have been burned at the stake for and it was just ‘being vegetarian’. Her cooking and hospitality were rich, the seeds of which she planted in us. I would like to say my parents have yielded somewhat of a harvest in my siblings and me.

It was in these days that I discovered and fell in love with the West Coast. The beaches, the Waitākere Ranges, and the winding roads that connected them. We tramped, cooked over fires, and were eaten alive by mozzies and sandflies. The Auckland Tramping Club’s hut up at Anawhata was a regular overnighter. It smelled of sweat, Swanndri’s and the smoke from the open fire where manuka cracked in the dark.

A few decades later, to this day, one of my favourite spots is still Maori Bay - the smaller beach just south of Muriwai. There’s something extreme about these beaches, unlike any others in New Zealand. East Coast beaches, lined with warm white sand and discarded ice block sticks, have sunrises and flowering Pohutakawa. West Coast Beaches are lined with wind-whipped trees, cold black sand and other-worldly sunsets. You stand on the edge of the world when you stand out there, like a page torn from a book, or the border of a painting.

And when you do stand atop Māori Bay, you look west through a gannet-and-salt-filled haze out towards Motutara Island or as McCahon imagined; Moby Dick. His painting Moby Dick is sighted off Muriwai Beach (1972) and the series of related sketches has stuck with me since I first encountered both beach and artist.

A Grain of Wheat (1970) is another favourite of mine. I studied it. I appropriated it. I practised painting the text of it, perfecting the method of paint-laden brush exhausted out to the dry full-stop. In ‘97, for my 21st birthday my sister gifted me a print of it, purchased from the Auckland Art Gallery. I had it framed well, paying more than I should have because I knew I had to, out of respect, and because I wanted to have it forever.

The print hangs on the wall of my lounge now, amongst works from friends, beneath a Mitsubishi heat pump, and above a sofa that has been beaten down by three children and the bottoms of countless guests.

McCahon’s painted words quote those of Jesus - one of his many agricultural parables - a seemingly simple analogy about this physical world disguising a message about a spiritual truth from another:

In truth, in very truth I tell you, a grain of wheat remains a solitary grain unless it falls into the ground and dies. But if it dies it becomes a rich harvest.

The text is arranged unconventionally; flat, scrawling and disjointed it forces the viewer to arrange into correct reading order. The meaning of the words on the other hand requires a deeper response; prompting us to consider nature and the everyday rhythms of life. The parable speaks of laying down our lives for something greater, of self-sacrifice and what can come from true selflessness; the type of sacrifice a devoted mother displays, or that costs you without the guarantee of reciprocation. Like a seed dying in the ground, choosing to lay down our own will can allow far more life to sprout.

The unassuming text also quietly reminds me of contentment. Meaningful art is never replaced or upgraded. One doesn’t look longingly for its newer version or consider trading up for another one with more features and sleeker proportions. No, you treasure it, are proud to have it, content to have only it. My print is numbered 121 of 500. It’s not the original. But, it’s my original; my 1 of 1.

Instead of constantly looking for the next thing, or the next destination, perhaps truly understanding and nurturing my connection to where I’m from is how I can harvest real riches. In a sea of ‘single-use’ and pop up culture I try to demonstrate this same idea of contentment as I lead our team at Supreme.

We work with farmers who till their own landscapes, cafe owners who rise in the dark day-in-day-out to show the simple yet powerful acts of hospitality every day, and loyal coffee drinkers who choose to support us even though we’re not always the new kid on the block. With some encouragement from them, and our talented team, we are embarking on our own journey of balancing economic success and environmental stewardship as we seek out the best long-lasting solutions to minimise the copious amounts of waste our industry produces.

We fly in aeroplanes to faraway places in order to visit our coffee-growing friends, shipping it back in big, thirsty ships that burn fossil fuel. We roast it in gas-burning machines that turn it rapidly from green to brown, pour it into plastic bags and drive it around the country in trucks, vans and hatchbacks. We’re very conscious of this, and are on the eve of phasing out plastic in favour of easily compostable materials. We’re replacing our fleet over time (as we can afford) with hybrid vehicles, and are about to publish our first sustainability report; not as green-washed marketing spin, but as an honest confession and to set a public goal for ourselves.

We’re trying to be better.