- Amy Howden-Chapman2014

- Ana Iti2020

- Andrew McLeod2007

- Andy Leleisi’uao2010

- Anoushka Akel2024

- Ava Seymour2009

- Ayesha Green2022

- Ben Cauchi2011

- Benjamin Work2024

- Bepen Bhana2016

- Campbell Patterson2015

- Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss2021

- Dan Arps2014

- Daniel Malone2014

- Emily Karaka2021

- Emma Fitts2018

- Eve Armstrong2009

- Fiona Pardington2013

- Gavin Hipkins2007

- George Watson2024

- Glen Hayward2011

- Imogen Taylor2017

- James Robinson2007

- Jess Johnson2019

- Jim Speers2010

- Judy Millar2006

- Kathy Barry2012

- Lisa Reihana2009

- Liyen Chong2012

- Louise Menzies2016

- Luise Fong2008

- Martin Basher2010

- Matthew Galloway2025

- Michael Stevenson2023

- Moniek Schrijer2021

- NELL2023

- Neke Moa2023

- Nicola Farquhar2018

- Oliver Perkins2017

- Owen Connors2023

- Regan Gentry2012

- Richard Frater2020

- Richard Lewer2008

- Rohan Wealleans2008

- Ruth Buchanan2013

- Sarah Smuts-Kennedy2016

- Sefton Rani2025

- Sorawit Songsataya2018

- Steve Carr2020

- Suji Park2015

- Tanu Gago2022

- Taro Shinoda2017

- Tiffany Singh2013

- Tim Wagg2019

- Wayne Youle2019

- Zac Langdon-Pole2022

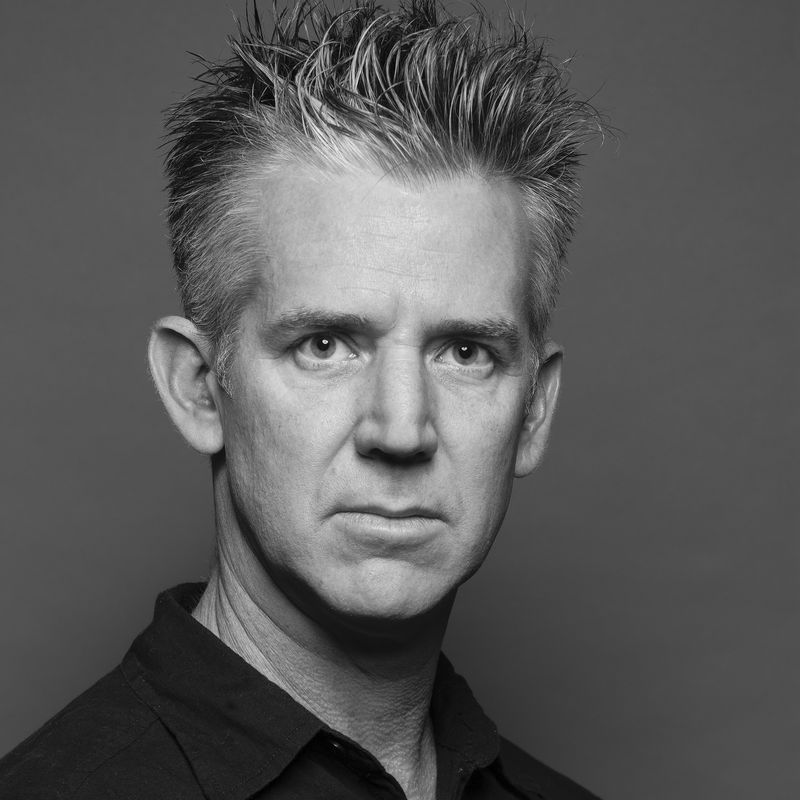

Wayne Youle

YEAR OF RESIDENCY

September - December 2019

Wayne Youle (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Whakaeke, Ngati Pākehā) was born in Wellington. He gained a Bachelor of Design from the Wellington Polytechnic School of Design in 1999. His bicultural heritage is reflected in his work; addressing issues of identity, race and the commodification of cultural symbols. He often uses humour to make his point. Wayne Youle’s work has been shown in national museums and public galleries throughout New Zealand and overseas.

Wayne Youle The hand of God 2012. Printed HB pencil, 1/325. Reproduced courtesy of the artist.

The works and lives of celebrated artists are closely studied; canvases are scrutinised for hidden meanings, biographical events weighed and parsed for significance, ideas and intentions imagined and interpreted. Colin McCahon is no exception, certainly not in the past year, when the centenary of his birth has been marked with a flourish of exhibitions, books, lectures and other activities around the country. What does this mean for the artist? What does it mean for other artists? McCahon’s influence is undeniable, but it’s often described in oppressive terms; he looms large, casts a long shadow, forms a towering block-lettered barricade for later artists to climb over or navigate around. It’s a fine line: if you’re not ostentatiously killing the giant, maybe you’re walking too closely in his footsteps.

For Wayne Youle, who undertook the Parehuia residency late last year, living and working near the modest Titirangi house McCahon shared with Anne McCahon and their children between 1953 and 1960 was an intriguing and somewhat daunting prospect. Like many artists, Youle sees McCahon as someone to look up to, but also live up to, once describing him as ‘the ultimate artist’, an epithet that reflected his respect not only for the quality of McCahon’s painting, but for the heft of his reputation. When Youle created 20 nickel-plated ‘art ancestor’ silhouettes in 2005, McCahon was represented with a booming I AM, alongside the likes of Shane Cotton and Gordon Walters. Youle pointedly dubbed the art-star-studded group Old Boys, but there was no question it was a club he was itching to join. He took the liberty of adding a reference to his own work as the 21st silhouette – an addition motivated by aspiration as much as irony. Later on, another work boosted, then chipped away at, the notion of a supreme artist atua. A simple yellow HB pencil, printed with the name ‘C. McCahon’, was reverently displayed on a custom mount. Youle titled it The Hand of God.

At 67 Otitori Bay Road, memory and myth are alive and well in the famous sun deck, the zigzag path, the shimmering, sun-dappled kauri trees. Accounts of McCahon’s time there, and the paintings he made, are an essential part of Aotearoa New Zealand art’s story of itself, the patina rubbed in a little deeper with every bus tour and private pilgrimage. Preparing to make his own temporary incursion into occupied territory, Youle turned away from McCahon’s paintings and towards another kind of mark-making. He began with the idiosyncratic alterations the artist made around the family home, and a set of hand-drawn building plans McCahon submitted to the Waitakere City Council in 1955. Part of a consent application to modify and extend the small original ‘weekender’-style cottage, their economical lines and soft red rectangles, austerely sketched onto butcher’s paper, held immediate aesthetic appeal. Equally importantly, they were physical evidence of something Youle and McCahon had in common; the experience of combining art with fatherhood.

Since the first of his three sons was born over a decade ago, Youle has come to recognise the tensions and tradeoffs that come with being both a committed artist and a present, loving parent. It was always going to be a delicate balancing act; a workaholic by nature and upbringing, he leans into his artistic practice with an energy that could easily tip over into obsession. In a former life, he spent 11 years as a rower, representing New Zealand in Surf Lifesaving competitions, and there’s a kind of butt-on-the-board work ethic that persists in his studio practice – progress ground out in relentless oar strokes, the daily effort that underpins success. That sort of intensity isn’t always compatible with parenting, where solitude and focus are in short supply. It’s no coincidence that the most significant work he made after becoming a father was a near-scale replica of his studio transformed into an impermeable bunker, wistfully titled ALONE TIME. As Youle’s children grow, and his parents age, time – passing, borrowed and exchanged - has become a recurrent motif.

Under the collective title Elevation – a reference to both renovation and reputation – the works Youle made during his residency feel their way around the gap between intention and achievement, between public and private, between the heroic and the human. The traces McCahon left behind him, some undertaken willingly as improvements or decorations, others forced by small, urgent needs, ranged from major projects – the construction of the deck, bathroom and bedrooms – to smaller accommodations like tables, shelving, steps, ladders and door handles. Some added character, though not necessarily comfort, to the cottage, like the “extraordinary glazing arrangement’[1] that combined two double-hung salvaged sash windows in an arrangement that resembles a cluster of slightly wonky Mondrians. This was an enticing trail of breadcrumbs for Youle, well suited to his own artistic skillset of observation, humour and magical thinking. The Elevation works frame McCahon’s artistic practice through the lens of the domestic, often buoyed by the sense of wonder Youle associates with the artist’s best works. In long JUMP (2019-20) the famous dotted trajectories of the Jump series are reimagined as a delicate, sunlit diagonal of threaded glass beads. Relocating the drama of an endless existential ellipsis from the symbolic space of the canvas into the vernacular of the everyday, they sound a soft repeat of the coloured marbles McCahon once used as window runners.

In other works, Youle takes us in the opposite direction. He lifts a small red square signifying Anne and Colin’s bedroom off the butcher’s paper, setting it instead at the very centre of a milk-green canvas. Without the scaled outline of the house around it, it both loses and gains meaning. Architecturally, it no longer makes sense, but as a portrait of the distilled pleasures and resentments of a marriage it is surprisingly evocative. Although they vary widely in materials and appearance, Youle’s works reflect his delight in precision and symmetry – in things made just so – and they often pack an unexpected emotional punch. Anyone who has ever ‘pinged’ a chalk line across a wall will recognise the fuzzy indigo verticals that Youle has spaced with scrupulous care, but his choice of title, lashing, propels us towards a much darker place, where perfectionism mutates into self-flagellation.

Over his years in Titirangi, McCahon increasingly powered up his practice, creating significant, large-scale works in greater numbers. Gradually, and especially after his four month trip with Anne to the United States in 1958, he came to resent the non-art tasks that infringed on his time, diverting his energies away from painting just as it felt most urgent. As his creative work escalated, more at home was left undone. Although McCahon was now earning a steady wage following his promotion to the position of Keeper and Deputy Director at Auckland Art Gallery, the family’s living arrangements remained far from comfortable.

Of the 30 works Wayne Youle made as a result of his residency, the only one not completed on site is also the largest – a very public putting-right of one of the jobs McCahon just never got around to. Visitors to Titirangi are often stunned to discover the open-air area underneath the house that functioned as the childrens’ sleeping area. McCahon’s building plans were approved in 1955 and he eventually constructed a small bedroom for his sons under his garage-studio, but for all the time they lived at Otitori Bay Road, his daughters hung blankets up as protection when it rained and became accustomed to seeing chickens on the end of their bunkbeds. This is the point where Youle’s empathy for the difficulties of juggling art with family responsibilities wears thin. “It’s like, ‘C’mon, dude, you were really that busy?’”[2]

Tartly titled the nurturer, Youle remedied McCahon’s shortcomings with a full-scale set of walls, scaled exactly to seal off the rooms and make them weather-tight. In keeping with the character of McCahon’s amateur DIY – ⅓ formalist, ⅓ ingenuity, ⅓ ‘that’ll do’ – the ‘walls’ are actually a bank of windows, their square frames letting in all of that miraculous Titirangi light, but skewed into slightly-off angles by their mismatched widths. The door at the centre is also meticulously observed, tapering down oddly to echo others in the house. The elaborate care Youle takes, in deliberate contrast to McCahon, is an undoubted twisting of the knife, but he doesn’t see the nurturer as a reproof, exactly. “It’s a letting, a venting” he says in explanation. “They’re just a job he didn’t get done.” In a strange quirk of chronology, Youle, the artistic descendant, is currently a decade older than McCahon was when he moved to Titirangi. He’s tailing the ghost of a younger man, shaking his head, cleaning up his mistakes, still marvelling at all he did achieve. There’s a sense that the wall, currently lined up down the centre of a space at Te Uru Waitakere Contemporary Gallery, is also a way for Youle to manufacture some room to move, as though if you hold him at the right distance, McCahon transformed from an overwhelming firmament into just another guiding star. Perhaps, too, it’s a warning directed at himself about the dangers of letting things slide, of believing your own hype.

For me, the most memorable work from Youle’s residency is one that expands to accommodate a variety of identities; one in which flawed artist-fathers and omnipotent world-builders might, momentarily, overlap. Titled the creator, it’s a spare, satisfyingly taut arrangement of brick-red rectangles and split circles. But if you look long enough, those abstract geometries re-form into the distinctively spread, carved fingers of a tekoteko, the kind that might adorn the gable of a wharenui. Closer again, and a flash of colour catches your eye. Those half circles are fingernails, and trapped under each is the mottled kaleidoscope of a lifetime’s worth of paint. Art is a messy business, the creator reminds us, and no one who’s any good gets out with their hands clean.

Essay commissioned by the McCahon House Trust on the occasion of Wayne Youle’s residency and resulting exhibition, Elevation, 26 September – 29 November 2020, at Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery.

1. McCahon House Trust Conservation Document.

2. This and all other quotes from Wayne Youle are taken from a conversation with the artist in August 2020.

Artist Artworks

Wayne Youle

A Sceptic and a Prophet walk into a bar (and talk through candlelight about things in common)

2019

screenprint on 300gsm Hahnemühle Fine Art paper, edition of 50

420 x 330mm

$500 (unframed)

Contact us to purchase this edition.