- Amy Howden-Chapman2014

- Ana Iti2020

- Andrew McLeod2007

- Andy Leleisi’uao2010

- Anoushka Akel2024

- Ava Seymour2009

- Ayesha Green2022

- Ben Cauchi2011

- Benjamin Work2024

- Bepen Bhana2016

- Campbell Patterson2015

- Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss2021

- Dan Arps2014

- Daniel Malone2014

- Emily Karaka2021

- Emma Fitts2018

- Eve Armstrong2009

- Fiona Pardington2013

- Gavin Hipkins2007

- George Watson2024

- Glen Hayward2011

- Imogen Taylor2017

- James Robinson2007

- Jess Johnson2019

- Jim Speers2010

- Judy Millar2006

- Kathy Barry2012

- Lisa Reihana2009

- Liyen Chong2012

- Louise Menzies2016

- Luise Fong2008

- Martin Basher2010

- Michael Stevenson2023

- Moniek Schrijer2021

- NELL2023

- Neke Moa2023

- Nicola Farquhar2018

- Oliver Perkins2017

- Owen Connors2023

- Regan Gentry2012

- Richard Frater2020

- Richard Lewer2008

- Rohan Wealleans2008

- Ruth Buchanan2013

- Sarah Smuts-Kennedy2016

- Sefton Rani2025

- Sorawit Songsataya2018

- Steve Carr2020

- Suji Park2015

- Tanu Gago2022

- Taro Shinoda2017

- Tiffany Singh2013

- Tim Wagg2019

- Wayne Youle2019

- Zac Langdon-Pole2022

Ayesha Green

YEAR OF RESIDENCY

September - December 2022

Ayesha Green - Educational Resource

Gate XIV Ayesha Green x Jamie Robert Johnston - November 2022

Ayesha Green (Kai Tahu, Ngāti Kahungunu (Heretaunga)) is an artist based in Tāmaki Makaurau. Ayesha has a Master of Fine Arts from Elam in 2013 and in 2016 she completed a Graduate Diploma in Arts specialising in Museums and Cultural Heritage. In August 2019, she was the winner of the National Contemporary Art Awards, and in 2020 was the inaugural recipient of the Springboard Award from the Arts Foundation. In May 2021, Ayesha was awarded the Rydall Art Prize in association with the Tauranga Art Gallery Toi Tauranga.

Recent exhibitions include; Folk Nationalism, Tauranga Art Gallery (2022); Good Citizen, Jhana Millers Gallery (2021); Wrapped up in Clouds, Dunedin Public Art Gallery (2020); Strands, The Dowse Art Museum (2019). Her work was included in Toi Tū Toi Ora at the Auckland Art Gallery and is currently working on a public sculpture commissioned by the Dunedin City Council.

The past is a construct made by those in the present. As time swirls forward, we come to see how our own understandings of the past become historicised, packaged, put away, maybe to be known, or maybe never be known again.

The past gathers dust. The past sits on a shelf. It is a book alongside other books. It is a stage upon which favourite taonga are rested, displayed, objectified.

Perhaps the past is a foundation on which to place the future, to construct new meanings, to reinterpret inherited histories, to gaze upon with eyes anew.

And what of the other eyes? What are they seeing?

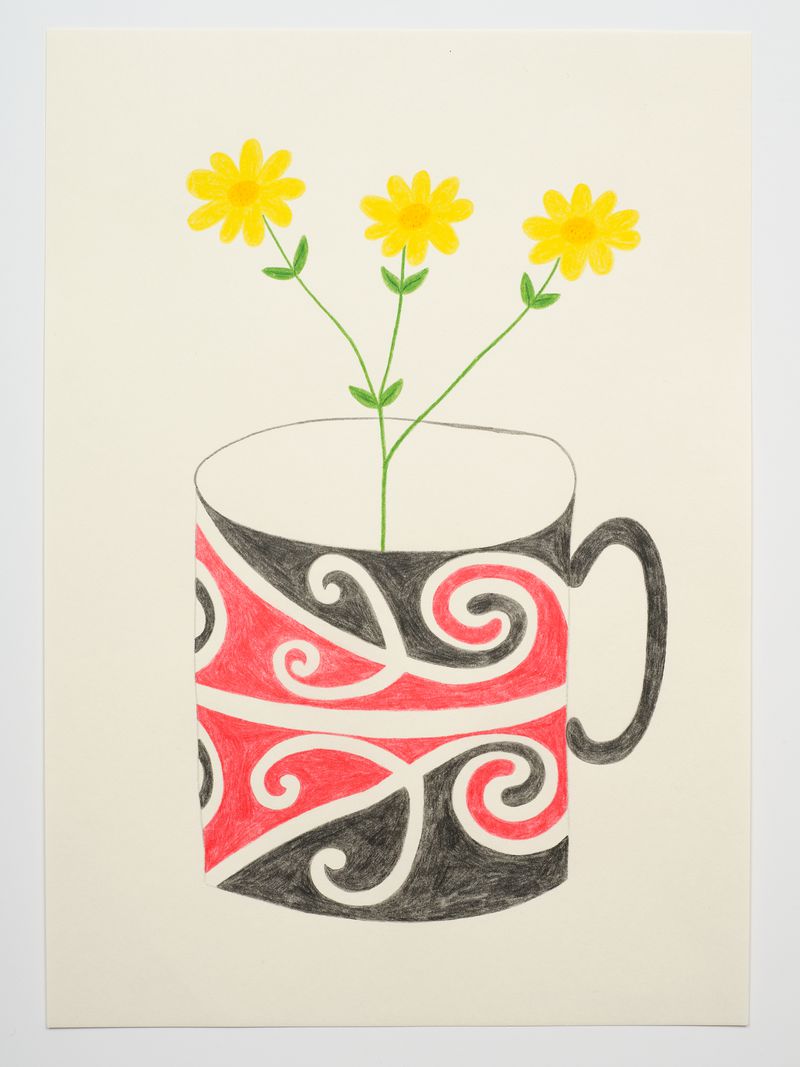

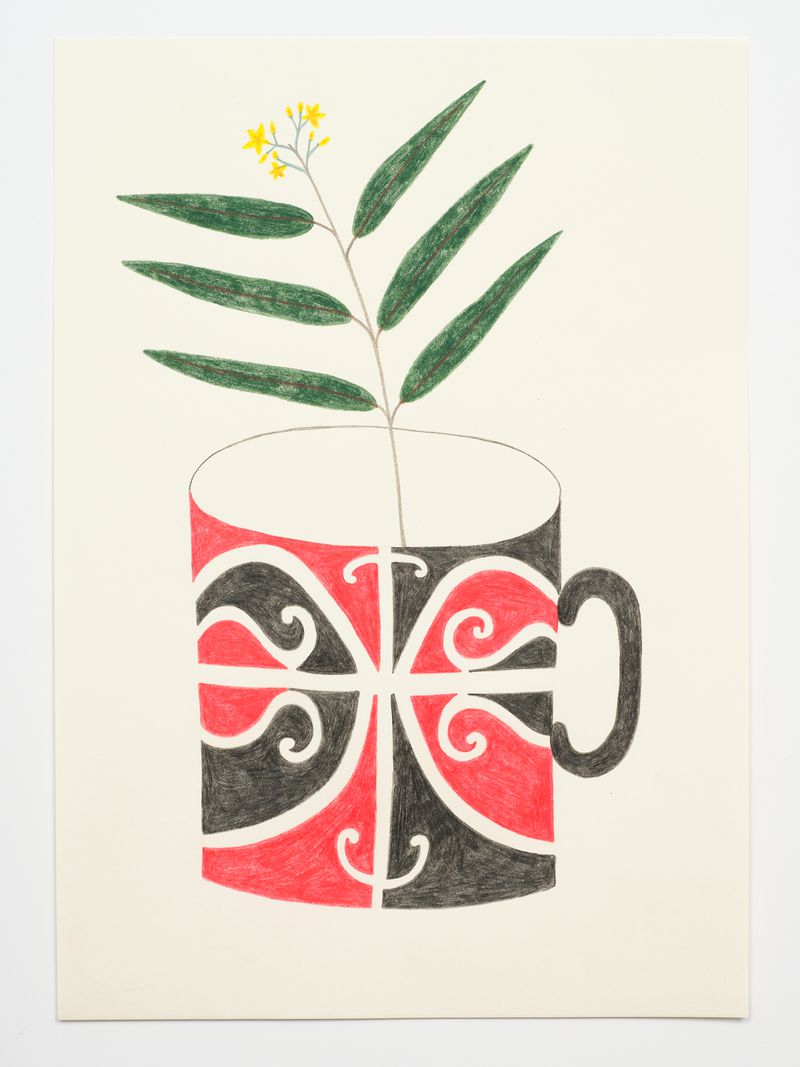

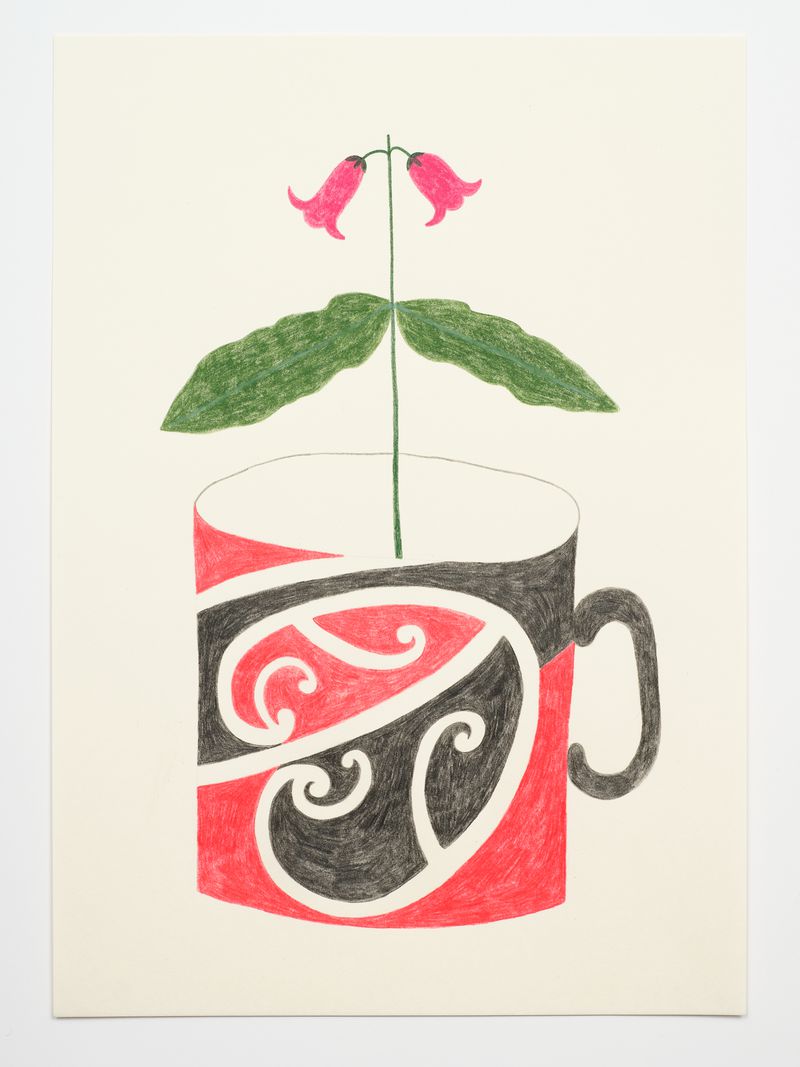

Pick up this cup, its surface resplendent in kōwhaiwhai. Tell me what you see. Here’s what I know: I can feel its heaviness in my hand, the handle thick, the surface worn by the hundreds of times it has been washed. It is my Koro’s cup and I know that when he asks for a cup of tea, that is the cup he wants it in. I know to take the teabag out and set it aside, I know that the teabags don’t go in the piggy bucket because I know that the pigs choke on teabags. I know that when the piggy bucket is full, Koro will empty it in the pigsty, wash it out with a hose and bring it back in.

Here is also what I know: this cup is mass-produced and can be found in souvenir shops, maybe even at the Warewhare alongside their range of kōwhaiwhai faux mink. I know that it is kitsch and there is a conversation to be had about appropriation and capitalisation of mātauranga but I also know that it is my Koro’s favourite cup. Ayesha has one of these cups too, and it has been kept full while she’s been working on these paintings and thinking of things like hierarchies of knowledge, ruined ecologies, and the commodification of, well, everything.

How about this facsimile of a Crown Lynn jug? While I speak of hefty cup handles, I recall reading how the Crown Lynn factory preferred to employ Māori to apply handles to cups. As explained by a previous factory manager, Fred Hoffman, “the natural rhythm and finger-ability of Maoris makes them twice as efficient as anyone else in the delicate process of making a cup handle look as though it had grown with the rest of the cup.”1 Perhaps it is this finger-ability of Ayesha’s that engenders the intricacy of painting lace tablecloths, a sign of feminine domesticity if ever there was one. The luxury of time is apparent in the creation of lace, a painstaking skill of delicacy and detail to which the presence of agriculture and food within Ayesha’s paintings are starkly contrasted. As the cost of living crisis continues to bear down upon us, these iconic foodstuffs stand in as the sinful pomegranate of the past, querying the immense profits made by supermarkets and the continued extraction of whenua to fuel the industries that keep our economies going.

What about the tin can of peaches? I have only ever seen these at marae and I am not sure non-Māori even buy at this size. Spoon by spoon the peaches will be doled out into pudding bowls, onto the tables set for hundreds. But hey, once it is empty at least you’ll have another tin for the steam pudding to go into.

Allow me to return to my Koro, to both of my Koros, who were regarded as gardeners. Gardeners who grew what was needed to nourish those they loved, collected seeds to sustain future seasons of their crops. What would they make of the capitalisation of something that should be a fundamental right? This is a question I would ask around their tables, spread with a tablecloth, set with food from these iconic New Zealand brands, alongside rēwena, relish and the most important kīnaki of all, their kōrero. But they are both gone now and I’m afraid that grief will turn me into an iconoclast, asking why everything must be extracted, bottled, canned, and sold; asking why our water is shipped overseas with claims of purity and ancient aquifers yet only 72% of our rivers are swimmable.2

In Tūhoe we speak of te matemateaone, the inextricable hononga between people and place, or more specifically, between Tūhoe and Te Urewera. I cannot write or think of land and my Koro without thinking of this, without thinking of his innate connection to whenua which is reified via whakapapa. Therefore, I cannot unlink the history of Colin McCahon, for whom Ayesha’s residency is named and funded, to Te Urewera. From the 1970s and the ensuing decades, this has been a fraught connection and one must only look to the commissioning, creation, theft, return and gifting of McCahon’s Urewera Mural to understand how complicated this is. Yet, whakapapa compels me to mention this. So too does the subtle yet weighty theme in Ayesha’s work that refers to hierarchies of knowledge: who are seen as knowledgeable and where did that knowledge come from? Whose histories have been seen as fundamental to our national understandings of self, and whose are lesser-appreciated and understood? Upon whose work do we display what we know?

My Koro, whose hands toiled the whenua and who linked us to various hapū throughout Rūātoki and beyond, was a descendant of Tutakangahau. Tutakangahau was the Tūhoe rangatira deemed by ethnographer Te Peehi to be a ‘tangata mōhio.’ He was the source of much of what Te Peehi built his career upon, and from whom some of the text for various Te Urewera paintings by McCahon was derived. Tangata mōhio, a knowledgeable Māori fit for the role of trusted informant, as determined and assessed by a Pākehā ethnographer.

With this I like to think of the words of the late, great Moana Jackson, who suggested that the way in which Māori came to be known through the breakthrough cinematic masterpiece of Once Were Warriors was limiting. That instead, the book and its film adaptation could have been titled Once Were Gardeners, Once Were Poets, Once Were Singers, Once Were Lovers.3 Moana also spoke of whakapapa as being a “series of never-ending beginnings.” It was whakapapa that brought me to this moment where I am writing of my tīpuna and my whenua, of crockery and McCahon; it was whakapapa that connected me to Ayesha, who is of Kahungunu like Moana. It is whakapapa that caused this confluence of histories, some of which are prone to clash, so that we will know the past again, take it off the shelf, pass it through each other’s hands and begin again.

Essay commissioned by McCahon House and Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery on the occasion of Ayesha Green’s Parehuia residency, September – December 2022, and the exhibition Still life, December 2022 – May 2023.

All photos by Sam Hartnett.

[1] Valerie Ringer Monk, Crown Lynn: A New Zealand Icon, Penguin, 2006, p.117

[2] Nick Smith, ‘90% of rivers and lakes swimmable by 2040’ – government press release, 2017. https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/90-rivers-and-lakes-swimmable-2040#:~:text=Currently%2072%20per%20cent%20by,2040%2C%20or%20400km%20per%20year%20.

[3] Moana Jackson, Once were gardeners - Moana Jackson on the scientific method and the 'warrior gene', 2009. www.youtube.com/watch?v=HfAe3Zvgui4

Artist Artworks

Ayesha Green

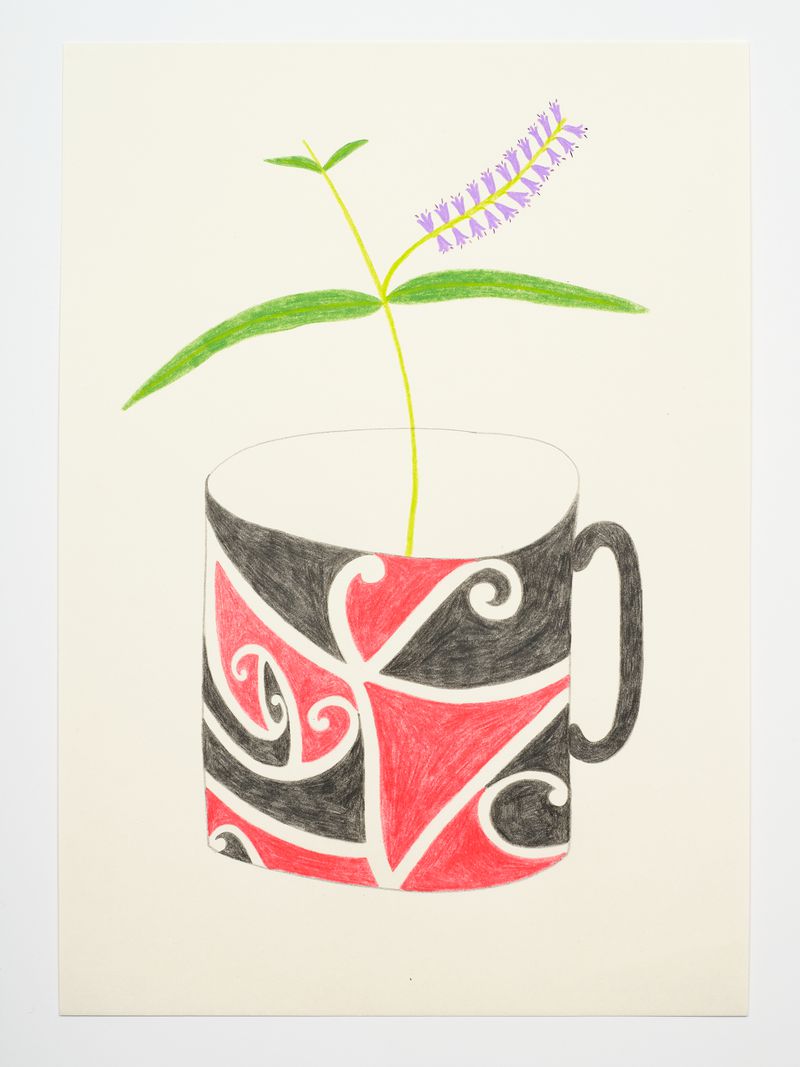

Untitled #5

2022

pencil on paper

420 x 300mm

SOLD

Photo: Sam Hartnett

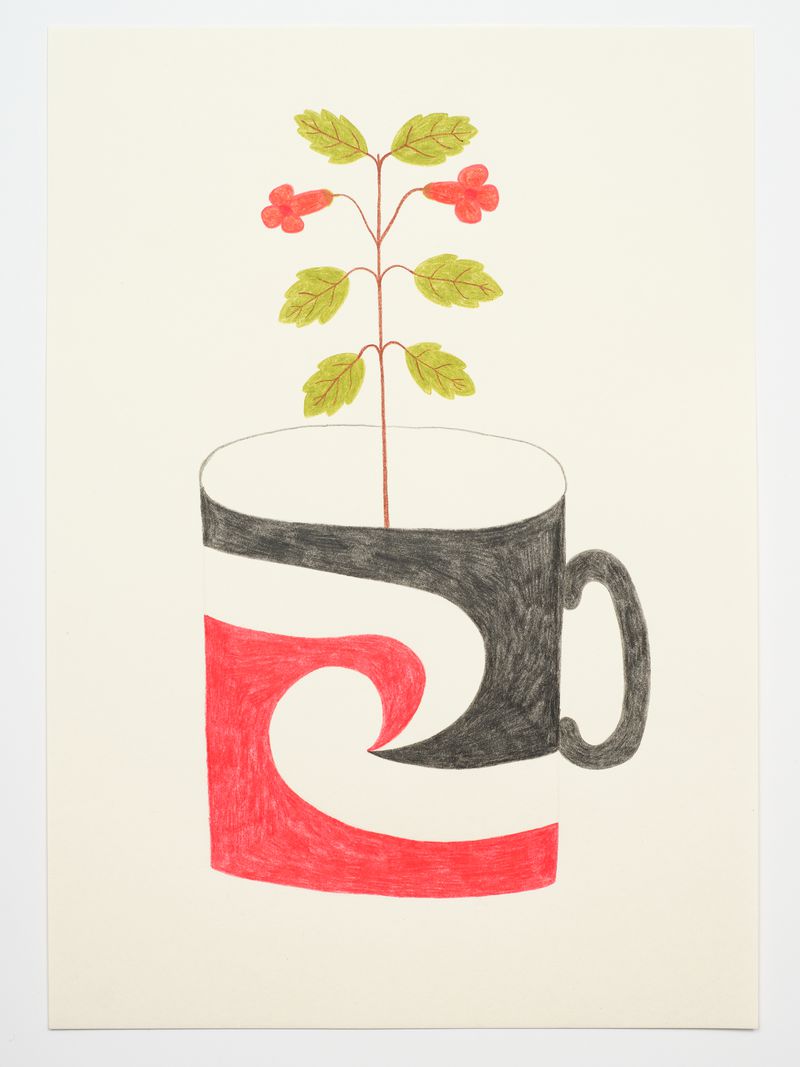

Ayesha Green

Untitled #3

2022

pencil on paper

420 x 300mm

SOLD

Photo: Sam Hartnett

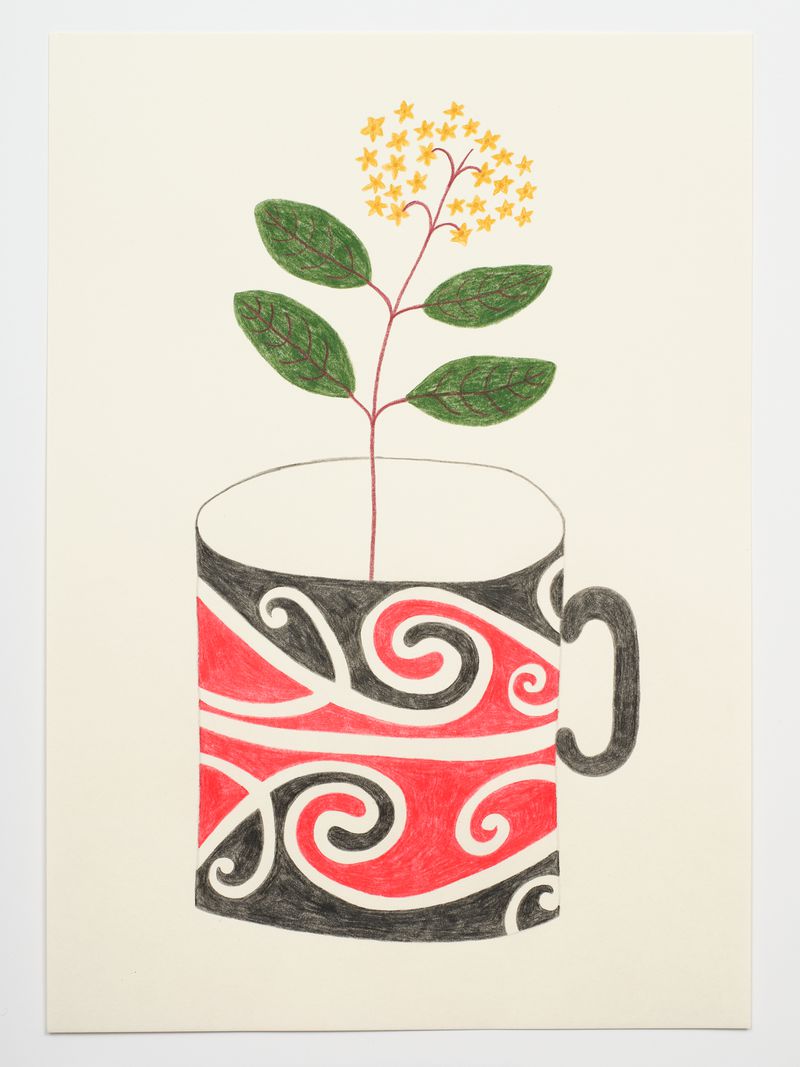

Ayesha Green

Untitled #2

2022

pencil on paper

420 x 300mm

SOLD

Photo: Sam Hartnett

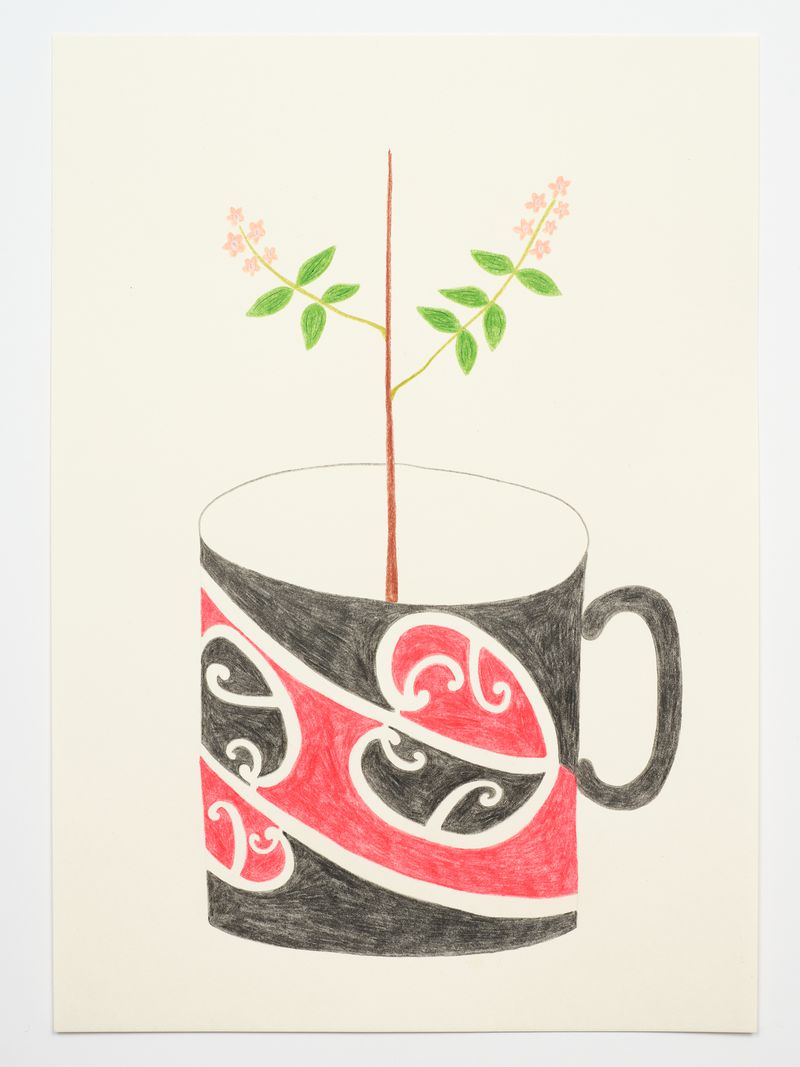

Ayesha Green

Untitled #8

2022

pencil on paper

420 x 300mm

SOLD

Photo: Sam Hartnett

Ayesha Green

Untitled #4

2022

pencil on paper

420 x 300mm

SOLD

Photo: Sam Hartnett

Ayesha Green

Untitled #1

2022

pencil on paper

420 x 300mm

Collection of McCahon House Trust

Photo: Sam Hartnett

Ayesha Green

Untitled #7

2022

pencil on paper

420 x 300mm

SOLD

Photo: Sam Hartnett

Ayesha Green

Untitled #6

2022

pencil on paper

420 x 300mm

SOLD

Photo: Sam Hartnett