The McCahon House Kauri Project

This collaborative project between McCahon House and The Kauri Project acknowledges the co-dependent relationship between the health and wellbeing of all nature – humanity and the natural world. We celebrate the mighty kauri tree as the godfather of Aotearoa’s native flora and fauna.

The genesis of the project dates back several years when kauri dieback was first discovered on-site at McCahon House Museum in French Bay. Since then, with support from Auckland Council Biosecurity, Plant & Food Research, Auckland Botanic Gardens, and Te Kawerau ā Maki, we grew a new generation of disease-free kauri that whakapapa back to Colin McCahon's beloved kauri that he loved and painted throughout his time living in Titirangi.

Read on for further information on the McCahon House Kauri Project.

Fredrik Hjelm harvesting the seed pods at McCahon House museum.

Kauri seed cones harvested from McCahon House museum.

McCahon House and Kauri Project team repotting the kauri saplings.

McCahon House Kauri Project saplings at Plant & Food Research, Pukekohe.

McCahon House Kauri Seed Collection

Kauri dieback was first detected on the McCahon House property in late 2008. By 2014 the trees were in severe decline and it was feared that they may not live for much longer or produce much more seed. It was highlighted that without immediate action it was likely the ‘McCahon House kauri’ and its genetic line would be lost.

Cone Collection:

Mature cones were collected from all kauri at the McCahon House Property at 67 Otitori Bay Road to retain the ‘McCahon House kauri’ whakapapa for future generations.

AC Biosecurity worked with arborists from ArborLab who climbed each tree and collected the cones.

Given kauri dieback disease presence and the risk of transfer, a biosecurity plan was actioned in order to carry out this operation. All footwear and equipment were thoroughly cleaned using Sterigene disinfectant before and after the process. The cones were taken directly from the tree and not allowed to touch any potentially infected material such as the soil around the trees.

A strong Health and Safety plan was also required given the poor condition of the kauri that were being climbed.

Propagation and growth:

Although the risk of transfer of KD to the seed, which are in cones as part of the canopy of kauri, is very low work to accurately define it had not been carried out. Because of this factor the propagation process had to be conducted in isolation of other activity to mitigate the risk.

Cones were placed in paper bags and stored at room temperature and allowed to ‘pop’ open naturally. Once the cones opened viable seed were sorted from the rest and potted into seed raising trays. They were then transplanted in to pots.

Throughout this process the seedlings have been regularly inspected and sampled to rule out the presence of kauri dieback. Kauri dieback has never been suspected or detected in any of the seedlings.

The propagation process has been carried out at Kari Street Nursery and Auckland Botanic Gardens under strict biosecurity protocols.

Fredrik Hjelm harvesting the seed pods at McCahon House museum.

A Love Letter to Kauri by Samuel Te Kani

Fascination with trees transcends the strictures of genre. From Anglo-Saxon fables about enormous Home Trees sheltering the world’s creatures in its Eden-like genesis, to the pensive bugbears of Tolkien’s forest guardians, the thread of tree-wondering is a long one with many gorgeous tangents. Little wonder that New Zealanders have such spiritual fealty to their natives, which any bush-trail infographic will tell you is a unique pantheon, each with its own gnarled characteristics and its own place in myth. What then underpins this nearly universal habit of looking at trees?

For starters, there’s the story of Rata forgetting to thank the protector-spirits of the forest before felling trees to make his waka. Here, there’s more to take away than the abject fear of gods in wrath. A figure of national virility akin to Māui, Rata is forced into a new relationship with his forest-surroundings. In meting out the necessary appeasements, he begins to experience the forest and trees as neighbourly beings in a living circuitry. Trees with personhood, trees as fellow members of a diverse community. In a flash, Rata discovers a richer world in which he coexists with tethered-entities as significant to his hero’s journey as humans. Networked beneath the ground and in the soil, as Māui to his own ancestors and descendants. Living entities with needs overlapping and intersecting with the world-making of tangata whenua, still, despite the proliferation of cities and so many presumptuous veins of concrete steel and glass. So presumptuous we might forget our shared origins - the earth, the soil.

With so many bush trails up north, my favourites being the ones cleaved to mountains and teethed with volcanic scoria, I remember being told that two totatara trees entwined like wedding arches made a portal. That when you pass through, you’re actually crossing some liminal veil marked by the handholding of these natives. I can’t verify this in lore, just the hearsay of locals and the impression of forest-magic left on me every time we found two such trees, meeting in the uncanny shape of a doorway. I can only imagine the local lore around kauri in their numbers and especial gathering in the north, holding together the country’s whittled tip like thonged timber holds the spearhead. In totara the fairy-ring trickery that spirits away the unwary, and in kauri the stronghold magic of bones.

Between sky-father Ranginui and earth-mother Papatūānuku, kauri scaffold all the gorgeous empty spaces in which tangata whenua have been afforded their dominion; a canvassing for story, play, dance, worship. In that tension of keeping lovers of sky and earth apart, kauri don’t buckle, they don’t sweat. They barely tremor in time’s march as amorous gods are kept at bay, staring longingly at one another, while their children bask in this new terrestrial arrangement. This is the way it is. But perhaps their children forget the shaky contingency of this order with the kauri, its stacked and groaning bones, and think the closing of day further off than it really is. And yet the kauri don’t buckle.

Cities have parks, a given. But beyond their aesthetic value, parks and gatherings of trees amidst the urban monotony engender the kinds of delicious relief normally reserved for the annals of tourism. Kauri are these but more, and like the strategy of parks to soothe urban desolation, they speak a salve. Even in the forests where they staunchly hold up life-giving canopies like the central-pillar of some florid pavilion, for which Tāne Mahuta gets an honourable mention. A prehistoric gargantua, a living god. Giving shelter and relief to those on the ground. Holding-to and holding together as the world turns around it, in teeming forest society a kingly pivot.

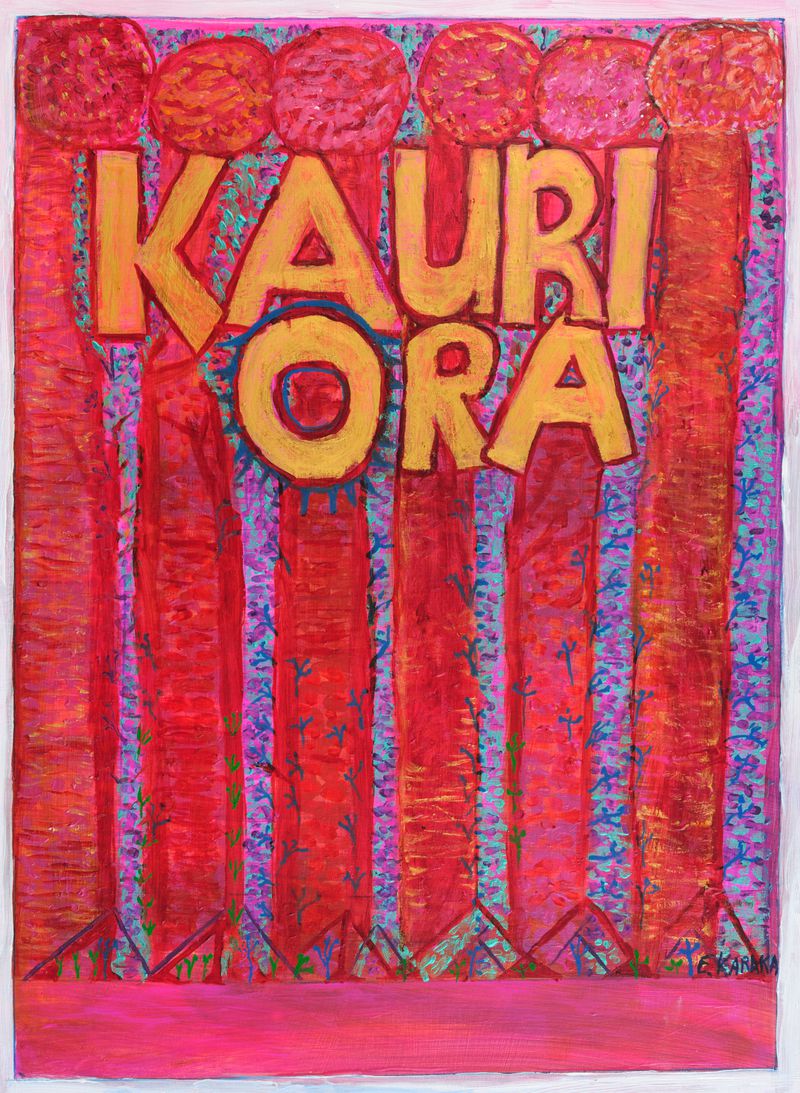

Emily Karaka’s work brings all this into blazing focus. In the midst of a die-back pandemic (not dissimilar to ours) effecting kauri forests on a massive scale, Karaka’s vision reinstalls kauri not as scenery, not as prettifying icons of the great kiwi pastoral, but as pillars. As the muscle of the land, guardians as mighty as they are attentive in the ever-listening sprawl of root-systems which hold us in place. More than the fodder of a once sterling industry which economically buttressed the far north, and now rests in skeletal ruin. Kauri ancestors then, still living even if under threat. And so, like the communities of the far north, proudly showing their resilience, ‘we are still here’ they say in dappling light. We are still here.

Commissioned by McCahon House Trust

Emily Karaka, Kauri Ora (red), 2021.